Полная версия

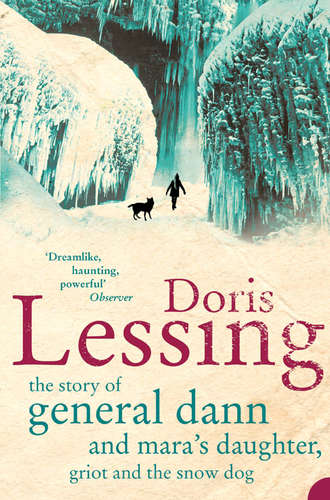

The Story of General Dann and Mara's Daughter, Griot and the Snow Dog

‘Drowned,’ said one youth and did not need to add, ‘I hope.’

Dann thought of his snow pup and remembered the little beast’s nuzzling at his shoulder.

Back at their landing stage they watched the animals leap off the old boat, swim to the shore and disappear into a wood.

Dann descended with Marianthe from their bedroom to the inn’s common-room, expecting hostility, but saw the young men who had gone with him being bought drinks and questioned about the trip. They were enjoying their fame, and when Dann appeared mugs were lifted towards him from all the room.

Dann did not join the five, but let them keep their moment. He sat with Marianthe, and when people came to lay their hands on his shoulders and congratulate him, he said that without the others, nothing could have been achieved.

But no one had ever gone so near the ice cliffs, until he came to this island.

And now Marianthe was saying that it was time for their room to be decorated with the wedding branches and flowers; it was time to celebrate their union.

Dann held her close and said that she must not stop him leaving – when he did leave.

In the common-room people were joking about him and Marianthe, and not always pleasantly. Some of the young men had hoped to take the place of her husband and resented Dann. He never replied to the jokes. Now he began to press them for another excursion. Had they ever seen the great fall of water from the Western Sea into this one? Marianthe said her husband wanted to make the attempt, but had been talked out of it. The feeling was that it would take days in even the largest fishing boat and it was not known if there were islands near the Falls where they could restock. But the real reason for the reluctance was the same: what for? was the feeling. Weren’t things all right as they were?

They were talking of a wildly dangerous event, which they knew must appeal to Dann’s reckless nature, and were satisfied with the trip to the ice cliffs: Dann and the fishermen and Durk were great heroes, and Dann did not say that compared with some of the dangers in his life it was not much of a thing to boast about.

He began going out with the fishermen; they seemed to think he had earned the right, because of his daring adventure to the ice cliffs. He learned the art of catching many different kinds of fish, and became friends with the men. All the time he was thinking of the northern icy shores and their secrets, hoping to persuade them to take him close again. He asked many questions, and learned very little. He was up against their lack of curiosity. He often could not believe it when he asked something and heard, ‘We’ve never needed to know that,’ or some such evasion.

The bitterness of his ignorance grew in him. He could not bear it, the immensity of what he didn’t know. The pain was linked deep in him with something hidden from him. He never asked himself why he had to know what other people were content to leave unknown. He was used to Mara, who was like him, and longed to understand. Down here on this lovely island, where he was a stranger only in this one thing – that these people did not even know how ignorant they were – he thought of Mara, missed her and dreamed of her too. Marianthe said to him that he had been calling out for a woman, called Mara. Who was she? ‘My sister,’ he said and saw her politely sceptical smile.

How it isolated him, that smile, how it estranged her. He thought that back in the Centre Griot would not smile if Dann talked of Mara, for he had lived at the Farm.

The pain Dann felt was homesickness, but he did not suspect that: he had never had a home that he could remember, so how could he be missing one?

He must leave. Soon, he must leave, before Marianthe’s disappointment in him turned to worse. But still he lingered.

He liked being with the girls who helped Marianthe with the inn’s work. They were merry, teased and caressed him, and made fun. ‘Oh, why are you so serious, Dann, always so serious, come on, give me a smile …’ He thought that Kira could be one of them – but even as he did, knew her presence would end the laughter. Well, then, suppose she had been born here, in this easy pleasant place, rather than as a slave, with the threat of being taken for breeding by the Hadrons, would she then have been kind and loving, instead of always looking for an advantage, always ready to humiliate? Was he asking, then, if these girls, whose nature was to caress and charm, had been born for it? But here Dann was coming up against a question too hard for him: it was a matter of what people were born with. Had Kira been born hard and unkind? If these girls had been born into that city, Chelops (now gone into dust and ashes), would they have been like Kira? But he could not know the answer, and so he let it go and allowed himself to be entertained by them.

Now a thought barged into his mind that he certainly could not welcome. If Mara had been born here, would she, like these girls, have had adroit tender hands and a smile like an embrace? Was he criticising Mara? How could he! Brave Mara – but fierce Mara; indomitable and tenacious Mara. But no one could say she was not stubborn and obstinate – she could no more have smiled, and yielded and teased and cajoled than … these girls could have gone a mile of that journey she and he had undergone. But, he was thinking, what a hard life she had had, never any ease, or lightness, never any … fun. What a word to apply to Mara; he almost felt ashamed – and he watched Marianthe’s girls at a kind of ball game they had, laughing and playing the fool. Oh, Mara, and I certainly didn’t make things easier for you, did I? But these thoughts were too difficult and painful, so he let them go and allowed himself to be entertained.

He stood with Marianthe at her window, overlooking the northern seas, where sometimes appeared blocks of ice that had fallen from the cliffs – though they always melted fast in the sun. Below them was a blue dance of water that he knew could be so cold, but with the sun on it seemed a playfellow, with the intimacy of an invitation: come on in, join me … Dann asked Marianthe, holding her close from behind, his face on her shining black curls, if she would not like to go with him back up the cliffs and walk to the Centre, and from there go with him to see that amazing roar and rush of white water … even as he said it, he thought how dismal she would find the marshes and the chilly mists.

‘How could I leave my inn?’ she said, meaning that she did not want to.

And now he dared to say that one day he believed she would have to. That morning he had made a trip to the town at the sea’s edge that had waves washing over its roofs.

‘Look over there,’ he said, tilting back her head by the chin, so she had to look up, to the distant icy gleams that were the ice mountains. Up there, he said to her, long long ago had been great cities, marvellous cities, finer than anything anywhere now – and he knew she was seeing in her mind’s eye the villages of the islands; you could not really call them towns. ‘It is hard for us to imagine those cities, and now anything like them is deep in the marshes up there on the southern shore.’ Marianthe leaned back against him, and rubbed her head against his cheek – he was tall, but she was almost as tall – and asked coaxingly why she should care about long ago.

‘Beautiful cities,’ he said, ‘with gardens and parks, that the ice covered, but it is going now, it is going so fast.’

But she mocked him and he laughed with her.

‘Come to bed, Dann.’

He had not been in her bed for three nights now and it was because, and he told her so, she was in the middle of her cycle, so she could conceive. She always laughed at him and was petulant, when he said this, asking how did he know, and anyway, she wanted a child, please, come on Dann.

And this was now the painful point of division between them. She wanted a child, to keep him with her, and he very much did not.

Marianthe had told her woman friends and the girls working at the inn, and they had told their men, and one evening, in the big main room, one of the fishermen called out that they had heard he knew the secrets of the bed.

‘Not of the bed,’ he said. ‘But of birth, when to conceive, yes.’

The room was full of men and women, and some children. By now he knew them all. Their faces had on them the same expression when they looked at him. Not antagonistic, exactly, but ready to be. He was always testing them, even when he did not mean to.

Now one fisherman called out, ‘And where did you get all that clever stuff from, Dann? Perhaps it is too deep for us.’

Here it was again, a moment when something he said brought into question everything he had ever said, all his tales, his exploits.

‘Nothing clever about it,’ Dann said. ‘If you can count the days between one full moon and the next full moon, and you do that all the time, then you can count the intervals between a woman’s flows. It is simple. For five days in the middle of a woman’s cycle a woman can conceive.’

‘You haven’t told us who told you. How do you know? How is it you know this and we don’t?’ A woman said this, and she was unfriendly.

‘Yes, you ask me how I know. Well, it is known. But only in some places. And that is the trouble. That is our trouble, all of us – do you see? Why is it you can travel to a new place and there is knowledge there that isn’t in other places? When my sister Mara arrived at the Agre Army – I told you that story – the general there taught her all kinds of things she didn’t know but he didn’t know about the means of controlling birth. He had never heard of it.’

Dann was standing by the great counter of the room where the casks of beer were, and the ranks of mugs. He was looking around at them all, from face to face, as if someone there could come out, there and then, with another bit of information that could fit in and make a whole.

‘Once,’ he said, ‘long ago, before the Ice came down up there’ – and he pointed in the direction of the ice cliffs – ‘all the land up there was covered with great cities and there was a great knowledge, which was lost, under the Ice. But it was found, some of it, and hidden in the sands – when there were sands and not marshes. Then bits and pieces of the old knowledge travelled, and it was known here and there, but never as a whole, except in the old Centre – but now it is in fragments there too.’

‘And how do you know what you know?’ came a sardonic query, from the eldest of the fishermen. Real hostility was near now; they were all staring at him and their eyes were cold.

Marianthe, behind the counter, began to weep.

‘Yes,’ said one of the younger fishermen, ‘he makes you cry; is that why you like him, Marianthe?’

That scene had been some days ago.

And now, this afternoon, was the moment when Dann knew he had to go …

‘Marianthe,’ he said, ‘you know what I’m going to say.’

‘Yes,’ she said.

‘Well, Marianthe, would you really be pleased if I went off leaving you with a baby? Would you?’

She was crying and would not answer.

In the corner of the room was his old sack. And that was all he had, or needed, after such a long time here – how long? Durk had reminded him that it was nearly three years.

He went down to the common-room, holding his old sack.

All the eyes in the room turned to see Marianthe, pale and tragic. People were eating their midday meal after returning from fishing.

One of the girls called out, ‘Some men were asking for you.’

‘What?’ said Dann, and in an instant his security in this place, or anywhere on the islands, disappeared. What a fool he had been, thinking that the descent to the Bottom Sea and a few hops from island to island had been enough to … ‘Who were they?’ he asked.

A fisherman called out, ‘They say you have a price on your head. What is your crime?’

Dann had already hitched his sack on to his shoulders and, seeing this, Durk was collecting his things too.

‘I told you, I ran away from the army in Shari. I was a general and I deserted.’

A man who didn’t like him said, ‘General, were you?’

‘I told you that.’

‘So your tales were true, then?’ someone said, half regretful, part sceptical still.

Dann, standing there, a thin and at the moment griefstricken figure, so young – sometimes he still looked like a boy – did not look like a general, or anything soldierly, for that matter. Not that they had ever seen a soldier.

‘Nearly all were true,’ said Dann, thinking of how he had softened everything for them. He had never told them that once he had gambled away his sister, nor what had happened to him in the Towers – not even Marianthe, who knew of the scars on his body. ‘They were true,’ he said again, ‘but the very bad things I did not tell you.’

Marianthe was leaning on the bar counter, weeping. One of the girls put her arms round her and said, ‘Don’t, you’ll be ill.’

‘You haven’t said what they looked like,’ said Dann, thinking of his old enemy, Kulik, who might or might not be dead.

At last he got out of them that there were two men, not young, and yes, one had a scar. Well, plenty of people had scars; ‘up there’ they did, but not down here.

Durk was beside Dann now, with his sack. The girls were bringing food for them to take.

‘Well,’ called a fisherman, from over his dish of soup and bread, ‘I suppose we’ll never hear the rest of your tales. Perhaps I’ll miss you, at that.’

‘We’ll miss you,’ the girls said, and crowded around to kiss him and pet him. ‘Come back, come back,’ they mourned.

And Dann embraced Marianthe, but swiftly, because of the watching people. ‘Why don’t you come up to the Centre?’ he whispered, but knew she never would – and she did not answer.

‘Goodbye, General,’ came from his chief antagonist, sounding quite friendly now. ‘And be careful as you go. Those men are nasty-looking types.’

Dann and Durk went to the boat, this time not stopping at every island, and to Durk’s, where his parents asked what had kept him so long. The girl Durk had wanted was with someone else and averted her eyes when she saw him.

At the inn Dann heard again about the men who had been asking for him. He thought, When I get to the Centre I’ll be safe. In the morning, he sat in the boat as he had come, in the bows, like a passenger, Durk rowing from the middle, his back to Dann, like a boatman.

Dann watched the great cliffs of the southern shore loom up, until Durk exclaimed, ‘Look!’ and rested his oars, and Dann stood to see better.

Down the crevices and cracks and gulleys poured white, a smoking white … had ‘up there’ been flooded, had the marshes overflowed? And then they saw; it was mist that was seeping down the dark faces of the cliff. And Durk said he had never seen anything like that in all his time as a boatman and Dann slumped back on his seat, so relieved he could only say, ‘That’s all right, then.’ He had had such a vision of disaster, as if all the world of ‘up there’ had gone into water.

Closer they drew, and closer: as the mists neared the Middle Sea they vanished, vanquished by the warmer airs of this happy sea … so Dann was seeing it, as the boat crunched on the gritty shore.

That pouring weight of wet air, the mists, was speaking to him of loss, of sorrow, but that was not how he had set out from Durk’s inn, light-hearted and looking forward to – well, to what exactly? He did not love the Centre! No, it was Mara, he must see Mara, he would go to the Farm, he must. But he stood on the little beach and stared up, and the falling wet whiteness filled him with woe.

He turned, and saw Durk there, with the boat’s rope in his hand, staring at him. That look, what did it mean? Not possible to pretend it away: Durk’s honest, and always friendly, face was … what? He was looking at Dann as if wanting to see right inside him. Dann was reminded of – yes, it was Griot, whose face was so often a reproach.

‘Well,’ said Dann, ‘and so I’m off.’ He turned away from Durk, and the look which was disturbing him, saying, ‘Some time, come and see me at the Centre. All you have to do is to walk for some days along the edge.’ He thought, and the dangers, and the ugliness, and the wet slipperiness … He said, his back still turned as he began to walk to the foot of the cliffs, ‘It’s easy, Durk, you’ll see,’ and thought that for Durk it would not be easy: he knew about boats and the sea and the safe work of the islands.

He took his first step on the path up, and heard an oar splash.

He felt that all the grey dank airs of the marshes had seeped into him, in a cold weight of … he was miserable about something: he had to admit it. He turned. A few paces from the shore Durk stood in his boat, still staring at Dann, who thought, We have been together all this time, he stayed away from his island and his girl because of me, he is my friend. These were new thoughts for Dann. He shouted, ‘Durk, come to the Centre, do come.’

Durk turned his back on Dann and sat, rowing hard – and out of Dann’s life.

Dann watched him, thinking, he must turn round … but he didn’t.

Dann started up the cliff, into the mists. He was at once soaked. And his face … but for lovely and loving Marianthe he did not shed one tear, or if he did, it was not in him to know it.

He thought, struggling up the cliff: But that’s what I’ve always done. What’s the use of looking back and crying? If you have to leave a place … leave a person … then, that’s it, you leave. I’ve been doing it all my life, haven’t I?

It took all day to reach the top, and then he heard voices, but he did not know the languages. He sheltered, wet and uncomfortable, under a rock. He was thinking, Am I mad, am I really, really mad to leave ‘down there’ – with its delightful airs, its balmy winds, its peaceful sunny islands? It is the nicest, friendliest place I have ever been in.

After the soft bed of Marianthe his stony sleep was fitful and he woke early, thinking to get on to the path before the refugees filled it. But there was already a stream of desperate people walking there. Dann slipped into the stream and became one of them, so they did not eye his heavy sack, and the possibility of food. Who were they, these fugitives? They were not the same as those he had seen three years before. Another war? Where? What was this language, or languages?

He walked along, brisk and healthy, and attracted looks because of his difference from these weary, starving people.

Then, by the side of the track, he saw a tumble of white bones, and he stepped out of the crowd and stood by them. The long bones had teeth marks and one had been cracked for the marrow. No heath bird had done that. What animals lived on these moors? Probably some snow dogs did. The two youngsters – these were their bones. Dann had never imagined what he and Mara might have looked like to observers, friendly and unfriendly, on their journey north. Not until he saw the two youngsters, seemingly blown towards him by the marshy winds, until he caught them, had he ever thought how Mara and he had been seen, but now here they were, scattered bones by the roadside. That’s Mara and me, thought Dann – if we had been unlucky.

And he stood there, as if on watch, until he bent and picked little sprigs of heather and put them in the eye sockets of the two clean young skulls.

Soon afterwards he saw a dark crest of woods on the rise ahead and knew it would be crowded with people at last able to sit down on solid ground that was dry. And so it was; a lot of people, very many sitting and lying under the trees. There were children, crying from hunger. Not far was Kass’s little house, out of sight of these desperate ones, and Dann went towards it, carefully, not attracting attention. When he reached it he saw the door was open and on the step a large white beast who, seeing him, lifted its head and howled. It came bounding towards him, and lay before him and rolled, and barked, licking his legs. Dann was so busy squatting to greet Ruff that he did not at once notice Kass, but she was not alone. There was a man with her, a Thores, like her, short and strong – and dangerously alert to everything. Kass called out, ‘See, he knows you, he’s been waiting for you, he’s been waiting for days now and the nights too, looking out …’ And to the man she said, ‘This is Dann, I told you.’ What she had told her husband Dann could not know; he was being given not hostile, but wary and knowledgeable looks. He was invited in, first by Kass: ‘This is Noll,’ and then by Noll. He had found them at table and was glad of it: it was a good way to the Centre and his food had to last. The snow dog was told to sit in the open door, to be seen, and to frighten off any refugees sharp enough to find their way there.

Noll had come from the cities of Tundra with enough money to keep them going, but he would have to return. The food and stores he had brought, and the money, were already depleted. This was an amiable enough man, but on guard, and sharp, and Dann was feeling relief that Noll was the kind of fellow he understood, someone who knew hardship. Already the islands were seeming to him like a kindly story or dream, and Durk’s smiling (and reproachful) face – but Dann did not want to recognise that – a part of the past, and an old tale. Yes, the fishermen had to face storms, sometimes, but there was something down there that sapped and enervated.

In spite of the damp, and the cold of the mists that rolled through the trees from the marshes, Dann thought, This is much more my line.

Kass did not hide from her husband that she was pleased to see Dann and even took his hand and held it, in front of him. Noll merely smiled, and then said, ‘Yes, you’re welcome.’ The snow dog came from his post at the door to Dann, put his head on his arm and whined.

‘This animal has looked after me well,’ said Kass. ‘I don’t know how often I’ve had desperadoes banging at the door, but Ruff’s barking sent them off again.’

And now Dann, his arms round Ruff, who would not leave him, told how he had gone down the cliffs to the Bottom Sea and the islands, but did not mention Marianthe, though Kass’s eyes were on his face to see if she could find the shadow of a woman on it.

These two were listening as if to tales from an imagined place, and kept saying that one day they would make the trip to the Bottom Sea and find out for themselves what strange folk lived down there, and discover the forests of trees they had never seen.

When night came Dann lay on a pallet on the floor, and thought of how on that bed up there he had lain with Kass and the snow puppy, now this great shaggy beast who lay by him as close as he could press, whining his happiness that Dann was there.

Dann was thinking that Kass had been good to him, and then – and this was a new thought for him – that he had been good to Kass. He had not stopped to wonder before if he had been good to or for a person. It was not a sentiment one associated with Kira. Surely he had been good to Mara? But the question did not arise. She was Mara and he was Dann, and that was all that had to be said. And Marianthe? No, that was something else. But with Kass he had to think first of kindness, and how she had held him when he wept, and had nourished the pup.

In the morning he shared their meal, and at last said he must go. Down the hill the woods were still full of the fugitives, new ones probably. And now the snow dog was whining in anxiety, and he actually took Dann’s sleeve in his teeth and pulled him. ‘He knows you are going,’ said Kass. ‘He doesn’t want you to go.’ And her eyes told Dann she didn’t want him to go either. Her husband, in possession, merely smiled, pleasantly enough, and would not be sorry when Dann left.

Ruff followed Dann to the door.

Noll said, ‘He knows you saved his life.’

Dann stroked the snow dog, and then hugged him and said, ‘Goodbye, Ruff,’ but the animal came with him out of the door and looked back at Kass and Noll and barked, but followed Dann.

‘Oh, Ruff,’ said Kass, ‘you’re leaving me.’ The dog whined, looking at her, but kept on after Dann who was trying not to look back and tempt the animal away. Now Kass ran after Dann with bread off the table, and rations for the animal, and some fish. She said to Dann, out of earshot of her husband, ‘Come back and see me, you and Ruff, come back.’ Dann said aloud that if she kept a lookout she would see new snow dogs coming up the cliff and one could take the place of Ruff, for a guard dog. She did not say it would not be the same, but knelt by the great dog and put her arms round him, and Ruff licked her face. Then she got up and, without looking back at Dann and Ruff, went to her husband.