Полная версия

The Proving Ground: The Inside Story of the 1998 Sydney to Hobart Boat Race

THE PROVING GROUND

The Story of the Disastrous Sydney to Hobart Boat Race 1998

G. BRUCE KNECHT

COPYRIGHT

Fourth Estate

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

This paperback edition first published in 2002

First published in Great Britain in 2001 by Fourth Estate

Copyright © G. Bruce Knecht 2001

The right of G. Bruce Knecht to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780007292080

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2016 ISBN: 9780007392544

Version: 2016-01-29

DEDICATION

For Elizabeth

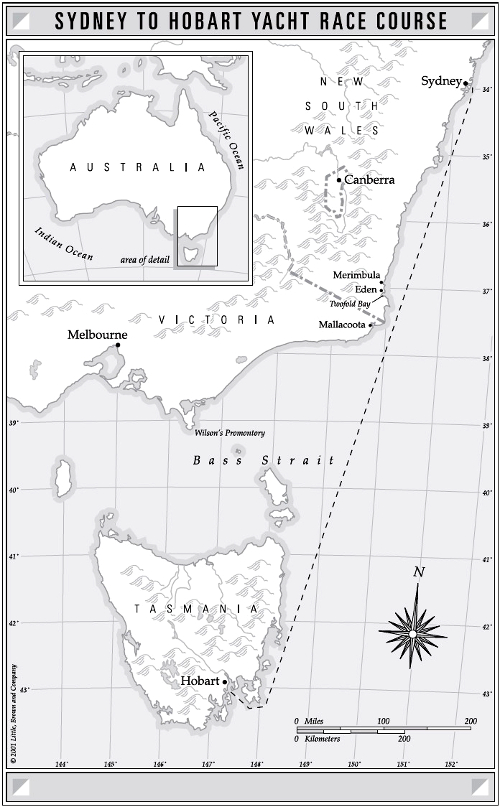

MAP

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

MAP

PROLOGUE

PART I: THE CALM

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

PART II: EAST OF EDEN

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

PART III: THE BLACK CLOUD

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

PART IV: ADRIFT

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

PART V: WAKE

36

37

38

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

PROLOGUE

LARRY ELLISON WAS lying in his bunk, calculating the likelihood that he would die.

He was, thanks to his stock in his company, Oracle, one of the wealthiest men in the world. But right now, he was seasick and miserable, and the NASDAQ seemed very far away.

One day earlier, he had seen what was coming. Looking at one of the two laptop computers used on his boat, he saw a satellite-generated image of a cyclone-like cloud pattern. Gripped with the same surreal feeling of disconnectedness he sometimes had when he was flying a plane on instruments, he asked Mark Rudiger, the yacht’s navigator, “Have you ever seen anything like this?”

Almost imperceptibly, Rudiger shook his head.

“Well, I have,” Ellison declared, his voice rising in bewildered outrage. “It was on the Weather Channel—and it was called Hurricane Helen. What the fuck is that doing here?”

Ellison’s yacht Sayonara had been struggling ever since. Steep forty-foot waves were sucking Sayonara up terrifying crests and then releasing it into deep troughs. Going up felt like riding an elevator during an earthquake; going down felt as though the elevator’s cable had snapped. The boat’s hull was made from two skins of carbon fiber surrounding a core of foam. Carbon fiber is a synthetic material with incredible strength for its weight, but Ellison knew that structural elements were beginning to fail. Several of the bulkheads, critical to maintaining the integrity of the hull, were no longer even attached. Large oval blisters had developed on the hull’s inside surface near the bow, indicating that the carbon skin had separated from the foam interior and that the two surfaces were grating against each other. Ellison knew that at some point the hull would become so weak that it would collapse like a paper bag against one of the waves. He also knew that Sayonara was too far out at sea to be reached by helicopter and that if he ended up in the water, he was unlikely to survive long enough to be rescued by another vessel.

By every standard but his own, Ellison, who looked younger than his fifty-four years, lived the life of dreams. On most days, he directed his company of 37,000 employees without even showing up at the office. He preferred to keep in touch by phone and e-mail from Katana, his 240-foot power yacht, or from his elegantly simple Japanese-style house in Atherton, California, where a pond was filtered like a swimming pool to ensure that the water was always crystal clear.

But Ellison was motivated by a kind of deeply rooted ambition that would never be satisfied. He was born to an unwed mother who gave him up for adoption. His adoptive father repeatedly told him he would never amount to anything. Since then, Ellison’s successes had only expanded his appetites. Although he carried himself with the bouncy manner of an adolescent who has just won an athletic championship, his dark brown eyes appeared coldly focused and constantly calculating. In a rarefied form of keeping up with the Joneses, much of the calculus involved his greatest rival, Microsoft’s Bill Gates. It was a rivalry that, in Ellison’s mind at least, went far beyond business and money. Ellison, who wrote short stories, played the piano, and piloted stunt planes in addition to winning sailing regattas, was constantly seeking to portray himself as more talented and more broadly gauged than Gates.

To Ellison, life was an experiment, or a contest, with a singular purpose: determining just how good he could be. Speed was an overriding theme. In addition to Sayonara, Ellison had a collection of high-performance planes and cars. With its 18,500-horsepower engine, Katana could charge through the water at thirty-five miles an hour. Ellison had given a lot of thought to his endless quest to go fast. “There are two aspects of speed,” he told friends. “One is the absolute notion of speed. Then there’s the relative notion—trying to go faster than the next guy. I think it’s the latter that is much more interesting. It’s an expression of our primal being. Ever since we were living in villages as hunter-gatherers, great rewards went to people who were stronger, faster.”

Ellison had entered the Sydney to Hobart Race because it is one of sailing’s most challenging contests. The danger had been part of the appeal. But as he lay in his bunk and looked around the cabin, where some of the world’s best sailors were lying on heaps of wet sails and retching into buckets, he was having second thoughts about his compulsive need to win.

Sayonara burrowed deep into each oncoming wall of water. Then, as if remembering it was supposed to float, it bobbed straight up to the wave’s crest. At that point Ellison began to count—“one one thousand, two one thousand”—as the bow projected out of the wave’s other side, again seeming to defy the natural order of things, until such a large section of the seventy-nine-foot vessel was hanging freely that gravity brought it down. That motion seemed to continue forever, although he had only reached “four one thousand” when the cycle ended with a violent crash.

This, he kept saying to himself, would be a stupid way to die.

1

PHYSICALLY AND CULTURALLY, the harbor is the center of Sydney, never more so than the day after Christmas, when the start of the 630-mile race from Sydney to Hobart, a city on the east coast of Tasmania, causes it to become an enormous natural amphitheater. Virtually everyone in Sydney watches the start, either in person or on television. Parks, backyards, and rooftops overflow with thousands of spectators, most of them with drinks in hand. The harbor itself is crowded with hundreds of boats and is noisy with air horns and low-flying helicopters.

No place is busier than the source of all the excitement, the Cruising Yacht Club of Australia. The club was founded in 1945, the same year it sponsored the first Sydney to Hobart Race. The CYC’s home is an undistinguished, two-story brick building on the bank of Rushcutters Bay, just a couple of miles east of downtown Sydney. Its pretensions, to the extent it has any, are related to “the Hobart,” as the race is usually called, rather than to social distinctions. Sailing has always played an important role in Australian life. It’s not surprising to hear policemen and taxi drivers describe themselves as yachtsmen. On an island as big as the United States but with a population of less than 19 million, access to the waterfront has never been limited to the rich. The CYC’s founders wanted to make sure it stayed that way, and in 1998 its 2,500 members paid annual dues of just $250, a tenth of what they were at some yacht clubs in the United States and Europe.

But although the CYC was modest in dues, it was not so when it came to its race. The main bar, which opens onto a large deck and a network of docks, is adorned with photographs of evocatively named Hobart-winning yachts: Assassin, Love & War, Ragamuffin, Rampage, Sagacious, Scallywag, Screw Loose, and Ultimate Challenge. In the slightly more formal bar on the second floor, a plaque carries the names of forty-three men who had completed at least twenty-five Hobarts. Although women had been competing regularly since 1946, none had yet earned a place on the plaque.

The CYC’s race draws the biggest names in sailing as well as prominent figures from other fields. Rupert Murdoch competed in six races, and his fifty-nine-foot yacht Ilina, a classic wooden ketch, came in second in 1964. Sir Edward Heath, the former British prime minister, won in 1969. Three years later, Ted Turner shocked other skippers by brazenly steering his American Eagle through the spectator boats after the start of the race—and then going on to win it. In 1996, Hasso Plattner, the multibillionaire cofounder of SAP AG, the German computer software giant, won in record-breaking time.

The very first race took place after Captain John Illingworth, a British naval officer who was stationed in Sydney during World War II, was invited to join a pleasure cruise from Sydney to Hobart, Australia’s second-oldest city and at one time an important maritime center. Only if it’s a race, he is said to have responded. It was agreed, and Illingworth’s thirty-nine-foot sloop Rani beat eight other yachts to win the first Hobart in six and a half days. Until the 1960s it usually took four or five days to complete the course. In the following decades, the average time required shrank to three or four. Plattner’s Morning Glory took just over two and a half days in 1996. The quickening pace reflected two of the biggest changes in competitive sailing: first, the move away from wooden boats, which were constructed according to instinct and tradition, to ones designed with the help of computers and built from fiberglass, aluminum, and space-age composite materials, and second, the transformation of what had been a purely amateur sport to one with an expanding number of full-time professionals.

For most of its history, sailing had proudly resisted the move to professionalism that had transformed many sports. But even Sir Thomas Lipton—whose five spirited but unsuccessful America’s Cup campaigns, which stretched from 1899 through 1930, earned him an almost saintlike reputation—understood the value of sponsorship. The publicity engendered by his prolonged pursuit of the Cup did much to make his tea a popular brand in the United States.

Since then, the level of competition has steadily risen, requiring increasing amounts of time and money. In 1977, Ted Turner spent six months and $1.7 million preparing his winning America’s Cup campaign. The only compensation he gave his crew was room and board. In 2000, five American contenders for the Cup planned to spend the better part of three years and more than $120 million preparing for the contest. Patrizio Bertelli, the head of the Italian fashion house Prada, provided the syndicate representing his country with a $50 million budget.

Ellison, who planned to compete for the America’s Cup in 2003, expected to spend at least $80 million. He would pay many members of his crew upwards of $200,000 a year for the more than two years they would train together. Ellison, who intended to sail on the boat—at least some of the time as its helmsman—would also take advantage of computer-based performance analyses and boatbuilding technologies that had been unthinkable even a few years earlier.

Turner, who had sailed on Sayonara for several races, was of two minds about what has happened to the sport he once dominated. During one race, he told Gary Jobson, his longtime tactician, “There are so many computers. Whatever happened to sailing by feel?”

As one of the computer industry’s pioneers, Ellison had no such qualms.

Ellison, who won the Hobart in 1995, had two goals for the 1998 race. First and foremost, he wanted to take the record away from Plattner. After Bill Gates, Plattner was Ellison’s most important competitor in the software business, and sailing had intensified their rivalry and added a deeply personal dimension. “It’s a blood duel,” Ellison would say, without the slightest suggestion that he was anything but deadly serious. He boasted that his yacht Sayonara, which didn’t race in the Hobart the year the record was set, had never lost to Plattner’s Morning Glory. Ellison and Plattner were not on speaking terms, but they had found other ways to express themselves. During one regatta, Plattner—incensed by what he felt was unsportsmanlike behavior by Ellison—dropped his pants and “mooned” Sayonara’s crew. Ellison’s other goal was to beat George Snow.

Snow, a charismatic Australian who had won the Hobart in 1997, and Ellison could hardly have been more different from each other. The crew on Snow’s yacht, Brindabella, was almost all amateur. On Sayonara, with the exception of two guests—one of them Lachlan Murdoch, Rupert’s eldest son and heir apparent—everyone was a professional. Ten of Ellison’s twenty-three crewmen were members of Team New Zealand, which had won the America’s Cup in 1995 and planned to defend it in 2000.

Ellison had always been upsetting traditions and bucking the odds. After his mother decided she couldn’t take care of him, he was adopted by an aunt and uncle. Ellison never got along with his adoptive father, Louis Ellison, a Russian immigrant who took his name from Ellis Island and worked as an auditor. Growing up in a small apartment on the South Side of Chicago, Ellison wasn’t interested in school or organized sports or anyone telling him what to do. “I always had problems with authority,” Ellison would explain. “My father thought that if someone was in a position of authority that he knew more than you did. I never thought that. I thought if someone couldn’t explain himself, I shouldn’t blindly do what I was told.”

After dropping out of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and then the University of Chicago, where he learned to write computer software, Ellison drove a beat-up car to California. Although he had little trouble getting hired, staying so was a different story. He stumbled through a raft of computer-related jobs until he heard about a new kind of software that could store and quickly manipulate large databases. Seeing its potential, he launched a business in 1977 that would become Oracle. The company doesn’t produce the kind of software that consumers buy or even know much about, but every organization that stores significant amounts of data needs it. For most of its first decade, sales doubled every year, so quickly that Oracle appeared to be on the verge of going totally out of control. Ellison’s personal life was equally rocky. He married and divorced three times, and he broke his neck in a surfing accident.

In 1990, Ellison was almost booted out of his own company after Oracle disclosed that some of its employees had booked millions of dollars of sales that hadn’t actually materialized. But by the mid-1990s it seemed that Ellison’s high-stakes, step-skipping management style was entirely appropriate for an industry that was changing faster than any traditional organization could. Ellison was confident that no company was better suited than his to capitalize on the burgeoning Internet. After all, the first generation of e-commerce blue bloods—Amazon.com, eBay, and Yahoo!—all relied on Oracle software. Thanks to them, and their gravity-defying stock prices, Ellison believed that the value of Oracle’s shares would also explode. And he thought that would enable him to achieve his ultimate ambition—to replace Bill Gates as the world’s richest man.

Ellison had always been interested in sailing. As a child, he imagined being able to travel to exotic places on the yachts he saw on Lake Michigan. Soon after he moved to California, he bought a thirty-four-foot sloop, although he gave it up because he couldn’t afford it. In 1994, Ellison’s next-door neighbor, a transplanted New Zealander named David Thomson, suggested the idea of building a maxi-yacht. The largest kind of boat permitted in many races, maxis are about eighty feet long. Ellison said yes, but he imposed a couple of conditions. First, he wanted it to be the fastest boat of its kind. Second, he wanted Thomson to do all the work. Thomson was a private investor affluent enough to live in Ellison’s neighborhood, but he wasn’t in a position to spend 3 or 4 million dollars for his own maxi. Deciding that it would be fun to oversee the design and construction of Ellison’s boat, Thomson readily agreed to his terms.

Typically, when someone decides to build a boat, he or she wants to be involved in the plans, but Ellison made it clear that he didn’t want to know about the details. When Thomson walked over to Ellison’s house with a set of engineering drawings, they spent only a few minutes talking about the boat before Ellison turned the conversation to his newest plane, which they discussed for more than an hour. Thomson did send Ellison occasional e-mail updates. At the end of one, Thomson, who had heard that Ellison was going to the White House for a state dinner honoring the emperor of Japan, asked about the protocol for such an occasion. “What will you wear? Do Americans bow to the emperor?” At the end of the e-mail, Thomson wrote, “Have a great time. Sayonara.”

Seconds after he pushed the SEND button, he sent another e-mail: “Sayonara. That’s not a bad name for a boat.”

Ellison didn’t answer Thomson’s White House etiquette questions, but to the name suggestion, he punched out an instant reply: “That’s it.”

Sayonara was completed in Auckland in May 1995, just a few days after Team New Zealand won the America’s Cup—a victory that the tiny nation commemorated with four ticker-tape parades and an outpouring of nationalistic pride rivaling the celebrations that followed World War II. Thomson had recruited almost half of Sayonara’s crew from the winning squad, and they flew to San Francisco for Sayonara’s inaugural sail shortly after the last parade. Thomson hired Paul Cayard to be the boat’s first professional skipper. Cayard, who was the lead helmsman for Dennis Conner on Stars & Stripes, the boat that lost the Cup to the Kiwis, had competed in a total of five America’s Cup regattas and in 1998 won the around-the-world Whitbread Race. To round out the crew, Cayard recruited several other members from Stars & Stripes to sail on Sayonara, creating a dream team of American and Kiwi yachtsmen.

When they met on Sayonara’s deck in Alameda, across the bay from downtown San Francisco, the newly assembled crewmen were impressed by what they saw. Everything on the boat was black or white except for the red that filled the o in Sayonara’s name painted on the side of the hull. White hulls typically have a dull finish, but Sayonara’s reflected the shimmering water like a mirror. The 100-foot mast, which bent slightly toward the stern and tapered near the top, was black, as were the sail covers, winches, and instruments. Like most modern racers, Sayonara had a wide stern and a broad cockpit, on which stood a pair of large side-by-side steering wheels. Sayonara was narrower than most other maxis and, at twenty-three tons, lighter than most of its peers. The unpainted interior was carbon-fiber black. While there is nothing pleasant about a windowless black cabin, paint has weight, and the lack of it only emphasized the commitment to speed.

The front third of Sayonara was an empty black hole except for long bags of sails. There was a similar-looking black cavern in the back of the boat. Only the center section was designed to be inhabited by sailors, and even there the accommodations were spartan. Pipes, wires, and mechanical devices protruded from the walls, and nothing was done to cover them. Just as David Thomson had promised, Sayonara was a pure racing machine.

Within three years, Sayonara had become virtually invincible, winning three straight maxi-class world championships as well as the Newport to Bermuda Race, America’s most prestigious offshore race. Ellison couldn’t have been more pleased. “I could have bought the New York Yankees, but I couldn’t be the team’s shortstop. With the boat, I actually get to play on the team.”

Getting to know the crew was part of the fun. Ellison discovered that many of them shared his interests in planes and fast cars, and he enjoyed being with men who were driven and competitive but wanted nothing from him beyond the chance to sail on Sayonara. Ellison was so pleased by his crew and so confident of their abilities that in 1997 he arrived at the maxi championship regatta, which was held in Sardinia, with Rolex watches for every crewman. They had been engraved SAYONARA. MAXI WORLD CHAMPIONS. SARDINIA 1997 long before the racing began.

During that regatta’s penultimate race, Hasso Plattner’s Morning Glory was winning until the halyard that held its mainsail broke and the sail collapsed. Seizing on the opportunity, Sayonara, which had been in second place, took over the lead. For the rest of the race, it “covered” Morning Glory: whenever Morning Glory tacked, Sayonara also turned so that it always stood between its opponent and the finish line, making it virtually impossible for Plattner to regain the lead, even after his crew rigged a new halyard. Covering is standard racing procedure, but it infuriated Plattner. Even worse, by winning that day’s race, Sayonara clinched the championship. Ellison didn’t have to sail on the last day to win the regatta, and he decided not to. Plattner considered Ellison’s behavior unsportsmanlike. “I have only the worst English words to provide for them,” Plattner said later.