Полная версия

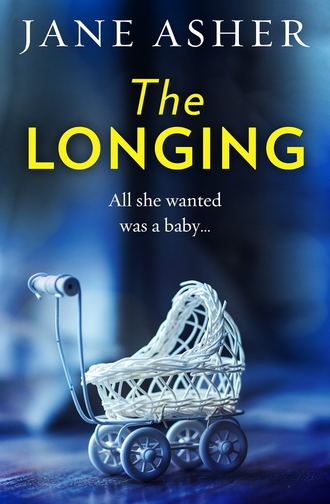

The Longing: A bestselling psychological thriller you won’t be able to put down

It would have been hard to imagine a less clinical setting. The hall was carpeted and lit by chandeliers, but the air of luxury was mitigated by a large, practical reception desk placed across the entranceway, almost hiding the two computer screens and the smiling girl positioned behind its high wooden façade. ‘May I help you?’ she enquired, with scarcely a hint of the adult-talking-down-to-child tone that Juliet tended to expect from anyone in the medical world when addressing a patient.

‘I’m Michael Evans, and this is my wife. We’ve come to see Professor Hewlett.’

Juliet looked up quickly, half anticipating a look of pity and superiority on the girl’s face, but catching only a smile of genuine warmth and apparent understanding. She felt Michael’s arm move to rest on her back, as if he sensed her wariness.

As they were ushered into the waiting room and towards a large, comfortable sofa, Michael was puzzled by his sense of being in a fast food restaurant. Why did he feel he should be ordering breakfast? He looked up at what he had been aware of on the edge of his vision: a series of framed photographs of the medical team and staff was hanging on the wall, each subject wearing a cheerful, positive smile and bearing a name, qualifications and a job description. They looked so extraordinarily ready to burst into efficient enquiries as to what Michael would like to order (‘Eggs, sir? Will that be fertile or infertile, sir?’ ‘Just twins to go, please,’), that he had to shake his head to remind himself where he was.

In the armchair opposite sat a balding man of forty-five or so. He was leaning forward, resting his arms on his knees and holding one hand to his forehead, not moving or glancing up as the newcomers sat down. Michael reached for Juliet’s hand and gave it a little pat. He wanted to say something reassuring but felt the sound of his voice would intrude on the quiet, slightly melancholy atmosphere, and contented himself with a small clearing of the throat.

‘Don’t,’ whispered Juliet.

‘What?’ he whispered back, half aware of the man in the chair, who still hadn’t stirred. ‘Don’t what? Cough?’

‘Sorry, it doesn’t matter.’

They sat on in silence for a few minutes. A nurse walked in and over to the man in the armchair. She bent down and murmured something by his lowered head. Michael heard a muttered ‘Oh Christ,’ then, ‘Yes, yes all right. In a moment.’ After a few more words in the man’s ear, the nurse straightened up again and walked towards the door, turning to give him a sympathetic smile as she left. He raised his head and looked after her, then with a sigh rose slowly to his feet and stretched his arms behind him before giving them a little shake. He slowly walked out, still never glancing in the direction of the sofa.

‘Poor chap.’ Michael lifted his hand off Juliet’s and, in order to have an excuse to do so, dusted some imaginary specks off the shoulder of his jacket.

‘Why?’

‘Oh, I don’t know. He just looked a bit bloody miserable that’s all.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, I don’t know, he just looked a bit miserable. You know.’

‘How could you possibly know that? How could you possibly know that a man you’ve never seen before in your life and have only seen now for about two and a half minutes is “bloody miserable” as you put it? God, you’re so irritating sometimes!’

‘Julie, I understand how you’re feeling, but there really isn’t any need to be quite so unpleasant. I was only passing a conversational thought. It wasn’t meant to be in any way serious and I—’

‘Oh all right, all right.’

She dropped her head and Michael could feel the welling of despair in the slight figure next to him. He felt the familiar stab of the intense pity and love that overcame him every time he was reminded of just how deeply she was wounded by her childlessness, and of how much pain it caused her at the slightest provocation.

He put both arms round her and let her head fall on to his chest, laying his cheek on her beautifully dressed hair and smelling the familiar mix of perfume and faint shampoo. ‘It’s all right, darling. It’s all right. We’re going to sort it out, you wait and see.’

‘I’m so sorry, Michael.’

‘I know, I know.’

And she was. Sorry for her short temper, sorry for the way she snapped at him and took out her frustration on him – this kind, tolerant man she depended on and took so much for granted. Years of familiarity had made her careless of his feelings, but at times she could see only too clearly how she treated him, and she hated herself for it. The strain of the past months of making love to order had told on both of them. Even the simple gesture of holding each other had become inextricably linked with their determined attempts to conceive; it was hard to remember a time when they’d had close physical contact for the sheer joy of it.

‘It’s not you. I just can’t bear myself, you see.’

‘I know.’

‘No, I’m sure you don’t. You’ve no idea how I loathe myself most of the time.’ She was looking up at him now, still in his arms but pulling away slightly, not crying but with such despair in her eyes that Michael thought it must be only seconds until she was. ‘I feel so empty, and so foolish – it’s hard to explain – as if I’ve just been pretending – how can I—’

‘Pretending what?’

‘I don’t know how to – pretending to live. Pretending I was getting up, pretending I was going to work. No you don’t know what I’m talking about, of course you don’t. I mean – I’m a sham. I’m not real.’

Apart from the necessary discussions about the love-making cycle, it wasn’t often that the subject of the non-existent child was touched upon openly now. For most of the time it was left as an unacknowledged hollow at the base of their marriage, only occasionally referred to obliquely by Juliet as in, ‘Well, at least we don’t have baby-sitter problems.’ Or, ‘I don’t suppose we’d be able to afford this holiday if things had gone according to plan.’ The small upstairs room had always been called the nursery, and the name had become so familiar and ordinary that neither had thought to stop using the word when it became less and less suitable. They had discussed things enough to confirm a willingness on both their parts to pay their way out of the Situation if it were possible, but it always filled Michael with hope when he felt Juliet was trying to put across to him how she really felt. These moments often seemed to follow patches of intense irritation with him, as if something in her was fighting every inch of the way against revealing her true feelings until they burst out of her unbidden and released themselves in a wave of weeping.

It was this intense distress of Juliet’s that made it so difficult for Michael to talk about his own sense of inadequacy and loss. For a man who liked to think he was rational and in control of his feelings it amazed him how much guilt he, too, felt at his failure to produce the required son and heir (it never occurred to him to wonder why he always imagined his offspring as male). But it was more than that – he had unexpectedly found a deep sadness within himself at the thought of never carrying his child in his arms, never kicking a football in the park with a miniature version of himself, never proudly watching the young Evans collecting his degree. As time went by his thoughts became almost biblical: phrases such as ‘Fruit of his loins’, ‘Evans begat Evans’, ‘Thy seed shall replenish the earth’ rattled round his head. The child became a clear picture in his mind until he could have described every detail of hair, figure, expression and face as if the boy really existed. Sometimes he felt he was going mad, but comforted himself with the realisation that this life of the imagination at least gave him a release of emotion which might otherwise have unleashed itself on Juliet.

Even at work he remained good-natured and outwardly at peace. He sometimes envied the ability of his colleagues to release their frustrations in outbursts of swearing and shouting, marvelling at their capacity to show strong emotion on such subjects as parking fines or politics. He thought with amusement of how violent, on a scale ranging from parking meters to childlessness, the manifestation of his own unhappiness would be if it truly reflected the deep wells of despair buried inside him. Not that his restraint made him seem in any way weak or inadequate; on the contrary his gentle but slightly cynical analysis of office problems betrayed a wisdom and maturity that were clearly lacking in the overheated reactions of those surrounding him. His childhood in Nottingham, as the bright-eyed boy of the manager of a furniture shop and a piano teacher mother, had led him to be aware, from his entrance into the local grammar school to his departure from Manchester University with a degree in economics, of how much was expected of him. Ever since seeing his parents’ anxiety at his admittance of any blip in the smooth upward curve of the life they had planned for him, he had learnt to keep his worries to himself.

But the distress over the non-existent child was different. For the first time in his life he felt the lack of any kind of real escape valve for the emotional pressure building inside, but was inhibited by his keen awareness of her own suffering from unburdening himself to the only other person who would be completely in sympathy. He found himself becoming increasingly attached to Lucy, the labrador, but consciously steered clear of imbuing her with too many human attributes, having seen in other couples how easily a pet can become a child substitute, involving, in his eyes, a lack of dignity for both parties.

As it was, he liked to think that Juliet was unaware of just how much he minded, and concentrated on supporting and cheering her.

This policy may have been a mistake.

Chapter Three

‘And?’

‘Polycystic ovaries.’

‘Poly-what-ovaries?’

‘Cystic.’

‘Oh, right.’

There was a pause while Harriet let this mysterious information sink in.

‘And is that bad?’

The two women stared at each other for a moment, then Juliet made a face. ‘Well I suppose so.’ She went on looking across at her friend, then they both laughed. ‘Well, evidently.’ They laughed more. ‘How would you like cysts on your ovaries’. Not just one, mind you, not just your monocystic, but the full poly. It’s not madly glamorous is it?

Harriet was giggling now, bending over in her chair, relieved to see the old Juliet emerging once more out of the midst of this alien affliction. And Juliet was laughing in relief too, knowing this was the only person she could ever talk to in this way, able to unburden herself without facing the over-solicitous reactions of Michael or the demanding worry of her mother. She was always smugly aware of Harriet’s envy of her own happily surviving marriage, but Juliet’s searing jealousy of her friend’s two children counterbalanced it, giving them a spurious emotional equality. Juliet had sometimes imagined a world where the two of them could combine – a creature half-Harriet and half-Juliet; the perfect happily married mother of two. The other halves – merging to create a woman not only abandoned but also barren – could wander in some eternal limbo for those that don’t fit, for those that break too many of the rules of social acceptability.

‘No, but I mean what can they do about it? Can’t they sort of scrape them off or something?’ This produced another burst of giggling. Harriet scooped her long brown hair (too long for thirty-five as Juliet sometimes idly considered telling her) back behind her ears and wiped smudged mascara from beneath her eyes.

Juliet leant forward and spoke more quietly. ‘You should see how they look inside you, it’s really bizarre. They said I had to have a scan, so of course I thought it would be like the ones you had with Adam, but it’s completely different.’ She pictured herself back on the couch in the small dark room in Weymouth Street; the radiographer had explained what was going to happen, but she had still been taken aback by the jellied penis-shaped instrument with its ultrasonic eye inserted gently into her vagina to gaze unashamedly up and around her womb and ovaries like an all-seeing joyless dildo.

‘God, I just feel so pleased that they’ve found something. I don’t care what I’ve got so long as there’s something I can do. I should be dark, fat and hairy apparently.’

‘What?’

‘The typical polycystic woman is large, dark and hairy. But not always. Obviously. Can I have another glass of wine?’

‘Of course.’ Harriet stood up and reached across the coffee table between them for Juliet’s glass. ‘It’ll have to be the Bulgarian red now, that’s all I’ve got left. Are you sure you’re allowed to drink by the way?’ She moved towards the small kitchen, collecting an old newspaper and abandoned toy gun as she went.

‘Oh don’t be so silly, Hattie. Believe me, if I get pregnant I shan’t touch a drop, but at the moment they tell me anything that helps me to relax is good.’

‘OK. Fine. So how did you get these things?’

‘They didn’t exactly say.’ Juliet stretched in her chair and looked around the comfortable, untidy sitting room. Harriet’s second-floor flat in Pimlico had been a refuge for many years now, in spite of the painful reminders of babies and then, later, of young children that were invariably scattered about. ‘Where are the sprogs?’ she asked.

‘Peter’s got them for the weekend. They’re taking them to Chessington today I think. The ghastly Lauren likes fast rides apparently. She would, of course. Another point to her.’ She was calling from the kitchen, and Juliet thought how little bitterness suited her even from a distance. Her voice always changed tone when the ex-husband or his new love were mentioned, reminding Juliet of the early days at school when Harriet’s sneering and bullying had been so impressive and had made all the girls want to be in her gang. Only after the two of them had been friends for two or three terms had Juliet got to know her softer side which, as Harriet relaxed into the routine of boarding-school life, had become increasingly dominant – until eventually it was Harriet to whom Juliet turned for comfort and advice, and who took her completely under her wing and used her dominance protectively rather than aggressively. It was Harriet who had first realised that something was very wrong as she had watched the skeletal Julie undressing in the dormitory; Harriet who had seen the pocketed food, heard the retching and groaning from the lavatory late at night. Although she had been too young to put a name to it she had sensed very quickly that her friend needed help, and that something quite dangerous was inhabiting her, subtly changing her not only physically but also from within.

The pair had remained friends after they left school. Long indulgent letters were exchanged between Harriet’s bedsit in Paris, where she was taking an interesting but unproductive Fine Art course, and Juliet’s university flat in Exeter, descriptions of suitors dominating the narrative, detailing their prowess in activities ranging from electrical repairs to love-making. But when Harriet met Peter over coffee in the Louvre, a change in tone crept into the letters and Juliet soon sensed love in the air. Back in London a couple of years later they had married, and the original hard and dissatisfied little girl was buried beneath a mound of glorious and uncomplicated happiness.

Juliet had envied Harriet’s complete abandonment in love. Peter was her world, and it was quite startling to see how Hattie adored him. It was the sort of love, Juliet supposed, that most people find only once in a lifetime, and some never find at all. Her own feelings for Michael seemed so contained in comparison, and Juliet often idly wondered if what she felt for him perhaps wasn’t love at all, but a convenient liking and companionship which, overlaid with the glitter of lust, had appeared to be deeper and more important than it actually was. But when the phone call had come from Hattie late that night; when the strange, thick voice had told of her misery at Peter’s infidelity and of her utter hopelessness faced by a future without him, Juliet had had enough of a glimpse into the open soul to see the torment that is always waiting on the other side of such all-encompassing love.

She had thought, gratefully, never to know it herself.

Juliet abandoned the car deep in the recesses of a public car park in Streatham and took from it a large brown holdall and the precious shopping basket with the thankfully sleeping baby in it, and carried them outside. It was almost dark, and she instinctively kept away from the streetlights as she walked quickly towards her destination. A lucky chance had led to her discovery of the semi-derelict house in Andover Road some weeks before; several wrong turns taken unthinkingly while coming back from a shopping trip had led her deeper and deeper into the unknown territory. She had pulled over to the side of the road and taken out her A–Z, but had soon found herself lost yet again in the thoughts that were then dominating nearly every waking moment. Gazing up at the row of abandoned houses alongside her she had sensed a solution, and had begun to formulate her terrible plan.

Now at last she was here. She had her baby back and all else would soon fall into place; when she was ready she would call Anthony and he would come, of that she was sure. Checking both ways to make sure that no one saw her, she slipped down the path along the side of the house and forced her way in through the broken door at the back, then climbed the stairs to the first floor. Once in the large front room she took a car rug out of the holdall, gently lifted the baby from the basket and then placed him carefully down on the tartan wool. He stirred a little in his sleep but didn’t wake, dreaming now of food instead of crying for it; feeling in his dream, rather than seeing, the comforting embrace of his mother and the rush of sweet, warm milk. His brain was as yet filled only with sensations and needs, with emotions, pictures and desires, with no memories older than a few months.

Juliet undid the poppers of his baby-gro, slipped it off his shoulders and rolled it down over his arms and legs. She pulled open the sticky tabs of his nappy and slid it from beneath his body, wincing a little involuntarily at the strong smell of ammonia. He stirred and whimpered. She looked down at his naked form, lit only dimly by the orange light from the lamp post that stood a few doors down the street, and found herself quietly crying. She bent her head to kiss him on his rounded belly, then laid her cheek lightly against him, not letting any of her weight rest on him, but touching him just enough to feel the warm beating softness.

‘Oh my dearest, dearest darling. Oh my sweetest darling. Oh my lovely baby.’

She lifted her head again to look down at him, seeing the gleam where her wet cheek had pressed against him, then as she gazed at him began to feel frightened. She sat up quickly and took off her blazer and laid it over him, panicking at the thought that he was cold. It was very quiet, and the silences between the baby’s whimperings were only broken by the noise of occasional cars turning into the small street, throwing odd swinging shadows from their headlights on to the walls and ceiling of the room as they negotiated the nearby corner. The whiteness of their lights and the thrust of their engines cut through the orangey quietness in sudden bursts of intensity, stirring the unease inside her, and leaving her each time more threatened by the silent darkness in between. She had never before been inside the room, but had assumed it would be completely empty, and only now did she begin to wonder what unknown objects were lurking in the corners, or what remnants of human occupation might be mouldering in unsavoury piles in the shadows. ‘Dear Lord, let him come soon. Let him come,’ she whispered, then closed her eyes, covered her face with her hands and swore quietly to herself, ‘Oh fuck it, fuck it, I haven’t told him yet have I? How can he come when you haven’t told him? Pull yourself together, Juliet, think it through. He’ll come when you tell him.’ She kept her face covered and breathed in the warm sweatiness of her hands mixed with a sharpness from the baby’s urine.

Then, as she knelt beside the baby, head still buried in her hands, eyes tightly closed, she heard something. Without moving her head, she snapped her eyes open behind her covering palms as she flinched and held her breath. She heard it again: a rustling behind her. Not daring to move for fear of what she might see, she kept completely still and focused every effort on listening, feeling her stomach clench in fear. Nothing. She could hold her breath no longer and began to let it out as quietly as she could, straining to listen as she exhaled, hearing only the smallest sound of her own breath escaping into the room, and of the baby’s fast, even breathing. Then – something again – a whisper of a rustle this time, still behind her, and a small dragging sound. As she turned and brought the hands down from her face, she saw the large figure of a man rising up out of the shadows in the corner and at the same moment she opened her mouth to scream.

Chapter Four

Michael and Juliet were quite taken aback when Professor Hewlett suggested IVF treatment. Test-tube babies were something you read about in the newspaper; something that happened to other people, like plane crashes and lottery wins, even something to be slightly disapproved of as unnatural and unnecessary. Back in the large, comfortable consulting room after the results of all the tests had come through, Juliet had tried hard to listen once more to the details of the condition of her ovaries and the problems with hormones, egg quality and elevated levels of this or that substance, but it wasn’t until towards the end of the consultation when the words ‘in vitro fertilisation’ hung in the air that she really tuned in. She sensed then that, although the professor was giving her and Michael every opportunity to feel they were taking some active part in the decisions and alternatives that appeared to present themselves at every turn, they were being guided inexorably towards a particular treatment and that if they did nothing but nod and appear to be following the arguments they would slowly but surely be set on the extraordinary course that must lie ahead.

‘We’ve had considerable success with using IVF in cases such as yours, and thirty-five is a good age to be trying. After thirty-eight or thirty-nine the eggs do tend to be of lesser quality, as I think you know, and although we have many successes after that age – and indeed over forty – you stand a higher chance if you start immediately. My inclination is not to go through the laser or diathermy route with your ovaries, I have a feeling we’d be wasting precious time and there are other factors which lead me back to IVF. We’ll have to monitor you very carefully as there’s a higher risk of overstimulating the ovaries when they’re polycystic, but as I say we’ve had considerable experience with other cases just like yours and I’m very happy to treat you along these lines. You’ll obviously need to discuss this between yourselves and you may feel you’d like a chat with your GP, but I see it quite clearly as the best course of action . . . I’ll get Sally to give you some leaflets and of course I understand that you’ll need to consider the financial implications.’

A strange sensation in the pit of Juliet’s stomach was puzzling her, exciting her, and she turned her thoughts inward to confront it. As Professor Hewlett paused and looked at her she felt she was expected to ask all sorts of intelligent, relevant questions, but for a moment she had to indulge herself in examining this little spark in the very middle of her being. She smiled to herself as she recognised it for what it was; something long forgotten but comfortingly familiar after such a long absence – hope.

Sensing that the appointment was nearing its close, she bent to pick up her handbag from the floor next to her chair, letting her hair fall forward over her face to hide the smile, then brushing it back with her hand as she straightened up again. ‘I don’t think we need even to discuss the money, do we, Michael? I’d just like to get going as soon as we possibly can.’