Полная версия

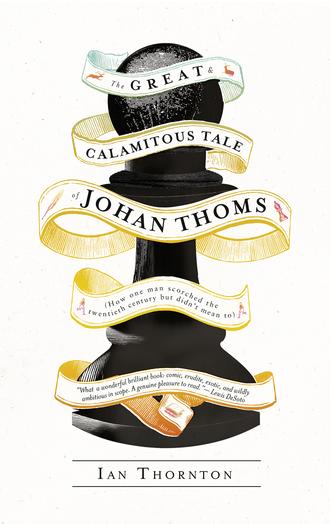

The Great and Calamitous Tale of Johan Thoms

He remembered every pupil he had ever had, their quirks and their strengths. He had a private joke with each of them. This endeared him to everyone at the school.

He instilled the love of knowledge into his own flesh and blood, too. Many evenings, Johan and Drago had sat by the fire in the living room of the old house in Argona as Drago set his eight-year-old boy mathematical problems of increasingly tough proportions, and within three years, high-end calculus, integration, differentiation, coefficients, constants, cosines, sines, tangents, and logarithms. Sheets covered by sigmas or dy/dx’s would be strewn across the deep red hearth rug, spilling over onto the surrounding mahogany floorboards. Pythagoras’s theorem on right-angled triangles followed. Then Drago passed on Pythagoras’s lesser-known theorem on beans. It is lesser known for very good reasons, for Pythagoras’s better work was—at this stage—well behind him.

Pythagoras reviled beans, for, they say, beans reminded him of testicles. Drago called it frijolophobia. Pythagoras developed an acute case of it, and could not even say the word bean.

Beans, however, just made Drago Thoms fart like a clogged sink.

* * *

THE BRIEF, YET VITAL STORY OF DRAGO’S OBSESSION WITH PYTHAGORAS

Pythagoras founded his own Orphic cult in Greece in 530 BC. His main and hugely controversial theory centered on the existence of zero. Previously, there had been no concept of zero. Greek digits had started with “one,” because who would take “zero” goats, “zero” donkeys to market?

Pythagoras proposed the existence of zero, and with it came its inevitable inverse of infinity. And if one believes in God, then one has to accept that there is a Satan. This, along with the predictable cyclical nature of mathematics, undermined the teachings of the Scriptures and the possibility of any all-seeing deity. It was heresy.

Society became split. Pythagoras and his Orphist followers broke away. They fled Greece and settled in the ancient city of Crotone, southern Italy, where they could live in relative safety from their now sworn enemies within the old order.

They really should have stuck to mathematics. Many of Pythagoras’s followers were forced to take vows of silence and to observe bizarre customs, which included the outlawing of beans. Initially, the word bean was banned. Later, all verbal communication was forbidden, apart from within the higher order.

Birds, particularly male swallows, were never allowed in any house.

Any dropped objects, particularly food, were never to be picked up. This, they believed, was bad luck. They would instead invite Pythagoras’s favorite hound, Braco, into the dining hall after each meal, to clean the floor of any tidbits. During thunderstorms, one’s feet had to remain on the ground. Any imprint of the body on bedclothes had to be smoothed out.

The pursuing zealots tracked down the heretic to his enclave in Crotone. They were feeling murderous, but in a way that only a lynch mob of very understanding, tolerant religious fundamentalists can be.

Some they slaughtered within the city walls, and they left some others castrated in the dusty streets. Then they chased Pythagoras and the rest out of Crotone. When the castrated victims rediscovered their vocal cords, Pythagoras was well out of town and making his escape. He came to, of all places, a bean field, which he had to cross in order to survive. His remaining trickle of fickle followers trampled through the crop; only Pythagoras had the conviction not to cross, not to make a Faustian pact with the diabolical bean.

And so he was cut down at the edge of the bean field, screaming anti-legume propaganda until his last breath. And THAT was the end of one of the greatest mathematical brains and maddest men the world had ever known.

* * *

It was Drago’s obsession with Pythagoras which eventually tipped him into his very own deep-trenched psychosis.

There were those locals who would suggest that in order for Drago to arrive at the front doors of madness, the journey need be neither long nor arduous. It was less a prolonged and tortured ride, and more a popping around the corner for a pint of milk. The effects on his family (and the unsuspecting world), however, would be catastrophic.

* * *

Drago, although fully versed in the hypotheses of Pythagoras, refused to subscribe to any of his teachings. He started to eat beans with every meal.

Before long, he would have bouts of eating ONLY beans, and beans of every breed. He became prolifically flatulent, often attempting traditional folk tunes with his emissions. Pythagoras became his nemesis, his Professor Moriarty.

Drago’s physical health began to deteriorate. His face was gaunt and shadowy. He became a bean expert, and grew beans in any spare patch of land or any darkened cupboard.

The vitamin deficiency from his bean-only intake progressed; previous eccentricities were magnified and new ones multiplied by his physical decline. His colleagues, who still had enormous respect for the man, tried to intervene, but the madness was taking over his behavior. He would be found carrying out more of the very acts against which Pythagoras had rebelled.

For example, during a thunderstorm, Drago would be found not only NOT touching the ground, but climbing trees or, worse, sitting on the roof of the house with his arms wrapped around his knees, his chin resting on them. He refused to use bedsheets, for fear of rising with them uncrumpled. He left beans in every room. He laid them out in a circle around the house and wore them on strings around his neck and wrists.

Furthermore, when he was at the dinner table, he would clumsily, but purposefully, knock food and utensils onto the floor, and slowly pick them up with a wide grin.

Johan’s mother, Elena, consulted her closest friends and then a doctor. She was concerned, more so when he started to leave all the windows open and, with bread and seeds, enticed into their house birds of every genus.

At school, meanwhile, any kind of quiet was a sign to Drago that his pupils were being tempted into a Pythagorean vow of silence. One member of the class always had to be talking, humming, whistling, or singing. Drago did not sleep night after night for fear of silence.

After many such sleepless nights, Drago began talking to himself on the way to school and around the grounds. This was simply not tolerable, so the headmaster took action. He successfully packaged the move as offering Drago a sabbatical to further his anti-Pythagorean studies. He was even afforded a meager pension, sold to him as a “study wage.”

For this, the Thoms family was eternally grateful, for during his sabbatical, Drago’s behavior was at least predictable.

So what if they had to tolerate swallows (and other hungry birds) in the house? Clarence, the ginger tomcat, was delighted, until, having won many battles, he lost the war. He was slung out on his furry ear for helping himself to one too many feathery enemies.

Because their child had left home, Elena could enjoy bedclothes in the relative sanity of a spare room. She and Drago did remain sexually active, though. Drago’s dedication to his research strangely concentrated his libidinal reserves, which were thrust upon and into an initially disturbed Elena. They regressed into humping like street dogs. Drago considered employing a cheap pianist to prevent a lack of noise.

The name Pythagoras was banned from the household, referred to only in Macbeth fashion, as “the Greek.”

Elena eventually embraced the new Drago, especially as much of his attention was now directed toward her. How many of her friends could boast of exploits such as theirs?

“The older the violin, the sweeter the music,” Drago would claim.

Having the house to themselves afforded them luxuries in their sexual deeds. Having her anal area dive-bombed by wild birds searching for crumbs while she fellated Drago was, however, a bridge too far.

Well, at least, at first.

* * *

So when, in June 1913, a letter arrived at the ancient University of Sarajevo addressed to Johan Thoms, it urged the recipient to consider making a small sacrifice for the greater familial good.

Johan considered bar work (he had made plenty of contacts from his time spent on the other side), laboring (but he was too uncoordinated to be of much use, those skinny matchstick legs and small feet), but it would really be more a question of what he could find.

He then recalled a summer over a decade before, when a wealthy young nobleman offered help of any kind should he or his family ever require it. He was still owed by the crazed, philandering, bug-eyed, buggering count whose buck had once almost taken the young lad’s eye and his life. It was time for Count Sodom to make good on his promise. Johan went to his old oak study desk, pulled out a yellowed notebook, and flicked through it. He came to a page written in a childish scrawl, very much that of a seven-year-old. Johan Thoms then took out his best writing paper, pen, and inkpot and started to write:

Dear Count,

I hope you may remember me . . .

Four

The Kama Sutra, Ganika, and Russian Vampires

Take the Kama Sutra. How many people died from the Kama Sutra, as opposed to the Bible? Who wins?

—Frank Zappa

June 9, 1913

After he had written his note, Johan Thoms spent the next part of the searing June day that followed reading and rereading a rare copy of the Kama Sutra, one of the first ever published in English, part of a trilogy. He had procured the collection by a stroke of luck. The tutor who had lent it to him lost his job at the college for exposing himself to a group of visiting nuns from County Cork. The professor fled the university in shame before Johan could return the books.

The books were to become Johan’s lifelong companions, to accompany him throughout his adventures as he traversed the continent and zigzagged his way through a self-induced mayhem. The trilogy (along with a number of other objects collected around this time) would then become the focus for his final whirlpool of psychosis. But I am rushing ahead.

The edition was a beauty, printed on thick paper. Its white vellum binding, trimmed with gold, boasted the original extended title:

The Kama Sutra of Vatsyayana

Translated from the Sanscrit

In Seven Parts, with Preface, Introduction and Concluding Remarks

The inside cover offered further intrigue and mystery:

Cosmopoli: 1883; for the Kama Shastra Society of London and Benares, and for private circulation only

(Bizarrely, Vatsyayana always claimed that he was celibate.)

The other books Johan had inherited from his nun-loving mentor bore equally intriguing titles.

Ananga-Ranga and the Hindu Art of Love

Translated from the Sanscrit and annotated by A.F.F. and B.F.R.

1885

and

The Perfumed Garden of the Sheikh Nefzaoui

Or the Arab Art of Love, sixteenth century

Translated from the French Version of the Arabian MS.

1886

Johan set about slow foreplay with the books, studying them tantrically. Intrigued by the genre, and knowing that barely a thousand copies had been published of Richard F. Burton’s unsurpassed translations, he then scoured the college and the city’s secondhand bookstores for a copy of The Arabian Nights. He would eventually find a copy under the pillow of the woman who would change his life. In fact, she had already set about this particular task, just hours before, at that hotbed of Oriental debauchery and degeneracy, the Old Sultan’s Palace.

Lorelei Ribeiro was currently lying in a cool bath in Suite 30 of the Hotel President, not more than three-quarters of a mile from where Johan was slowly digesting the ins and outs of coitus. Rolling around in the relaxing waters of her tub, this rare beauty would have been a picture for any man (as well as most women, hermaphrodites, and eunuchs) to behold. The bathtub brimmed with scented oils of gardenia and ylang-ylang. The smooth, dark skin of her legs shone with the oil as the back of her knees rested on the rim of the tub, her glistening fetlocks and feet dangling akimbo on the outside. Her head lay back, submerged to her brow. The ceiling fan whirred above enviously.

When Lorelei eventually did get out of her bath, with fingers still not crinkled, it was to head to her bed and the breakfast tray of luscious fruits and cold coffee which the room-service staff had left an hour previously. She sat on the white duvet in her bathrobe, towel wrapped on her head, and poured a healthy dose of strong cold coffee into her mouth. She turned on the gramophone and listened. A soothing harp filled the room, from deep shag carpets to palatial ceiling.

* * *

Later, in the heat of the afternoon, Lorelei flounced around Bascarsija and along the banks of the Miljacka, a glorious swathe in white, turning heads all along her route. Wives smacked husbands’ arms. Cars narrowly avoided hitting each other; trees braced themselves for a sudden strike from a fender. The early-afternoon temperature peaked and the locals sweated; the day seemed to stand still for a few minutes, as only summer days can. When Lorelei eventually sauntered back into the cool of the President’s lobby, the ceiling fans were rotating at full tilt, struggling against the early-evening southern European heat.

She instructed the bellhop to come to her floor, and the lift crawled upward, opening onto the third floor hallway, with its deep cream carpets centrally laid on dark brown oak floorboards. The sturdy white walls and high ceilings were interrupted by grainy sepia photographs of mustachioed young men in all-in-one swimsuits and of bonneted ladies in fields of knee-high daisies. One of the ladies showed just a hint of breast. This forced Lorelei to look twice as she stepped out, for the President did have the reputation of being a liberal spot.

The cage door closed behind her. Lorelei dispensed with her shoes. Her feet enjoyed the luxury of the crushed rugs en route to her suite. Manicured phalanges fingered the cold key into the lock.

* * *

Lorelei observed the evening’s arrival from her balcony. The quiet luxury inside the President was at odds with the smoky, squawking city. Both had once been heavily influenced by Islam and by the Turks. The hotel’s mystic Eastern design had evolved, however, into lush cream-and-scarlet carpets, deep mahogany pillars, hygienic modern conveniences, and Western ways. These now were juxtaposed with a metropolis still populated with ancient mosques and bearded street traders, apparently stubbornly lingering from the sixteenth century.

She looked at her thin gold wristwatch and involuntarily slowed her pace. Meanwhile, in the lobby, three dark-suited gentlemen removed their hats, announced their arrival, and headed for the bar.

Forty minutes later, in Suite 30, diamond earrings were clipped and cramponned, a sweet musk of Lyonnais parfum was pumped at the regulatory nine inches, and long black silk gloves were fixed. The thickness of the deep aqua curtains, twenty feet high, now kept out the evening buzz. An envelope had been pushed under Lorelei’s door announcing the arrival of her dinner guests.

Lorelei gathered herself. She headed for the door, head tilted, swaying elegantly.

* * *

The boys walked eagerly over cobbles, but not eagerly enough to prevent Bill from yawning as Johan outlined the theory of the sixty-four practices of the Kama Sutra. A woman who gained mastery of all sixty-four crafts was respected, took her place in a male-dominated world, and became known as a ganika. Bill told him to shut up, but Johan kept the word on his lips.

“Ganika, ganika, ganika . . .”

They entered a trinket-filled, rouge-lit taberne, and Cartwright bought two steins of cold pilsner. Even before he had settled into his seat, he started into a mad monologue. Five minutes passed before Johan realized he had not heard one single word.

“Never mind that, Billy Boy,” Johan interrupted. “Come on. Drink up.”

Johan was in a rush again. His nervous and sometimes infectiously uncomfortable energy was getting the better of him as he whispered to himself some words that kept repeating in his mind.

Glide gently, thus forever glide.

They soon emptied their glasses and disappeared down a side street, into the shadows of the gathered dusk.

“Bon vivants! Good livers!” Johan yelled as their glasses met in the next bar.

Johan told himself he was feeling happy, and bookmarked it for future reference so that he would not feel guilty about letting such a moment slip by him.

Glide gently, El Capitán! Glide gently!

* * *

Mario Srna, Lorelei’s closest ally in the embassy in Vienna, hosted a relaxed dinner at a fine Russian establishment, Troika, just two blocks from the President. Besides Lorelei, Srna’s guests were two old pals from the consulate. The dinner lasted a pleasant two hours, consisting of a deep scarlet beetroot borscht, heavily peppered, followed by sublime roast venison, locally bred from the grounds of the Count of Kaunitz himself—an eccentric, but owner of the finest beasts in the land.

Srna was even offered the animal’s head for his wall as a souvenir, a tradition of the time. He cordially accepted, as he was a gentleman with impeccable etiquette. To turn it down would have been an insult. The head was to be delivered to his town house in Vienna.

Srna was a slight, youthful forty-six-year-old, with clever brown eyes and a peerless generosity of spirit rare among diplomats. He was ambitious, but he achieved what he did through talent, quality, and vision, not Machiavellian techniques. Lorelei looked up to him, yet he was reliant on her as his eyes and his confidante.

The dinner guests were James Whitt and Herb LaRoux, from Boise, Idaho, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, respectively. They contributed adequate tales from the professional field and above-average insight into the realpolitik of Europe and the raping of Africa. They did a fine impression of homosexual twins who were attached at the hip and dressed like each other for reasons over and above cordiality. Srna suggested this to Lorelei as Tweedledee and Tweedledum disappeared off together for a second time.

“Silly fool!” answered Lorelei. “They are smoking opium in the back.”

Srna had had no idea.

“Don’t look so shocked, Mario, you big dummy,” she said, smiling. “Even Queen Victoria used to do it, you know that!”

“That is German propaganda, Lorelei!”

“It is NOT. And she was German, remember! Even Conan Doyle has Sherlock Holmes doing something like it to chase down Moriarty. They say he is addicted. Bram Stoker’s Dracula. The sucking of youth and never seeing daylight. It’s the height of fashion in London, and don’t look so prudish! If you want to be shocked, I will tell you what Prince Albert once had done to his bratwurst!”

When Lorelei had finished telling him, Mario Srna’s eyes nearly popped out of his head. He announced that he needed another vodka. The other two dinner guests meandered back from behind a thick curtain in lazy unison. “Na Zdarovye.”

“Vodka is always best tasted at a healthy distance from Moscow!” announced Srna philosophically. “Vodka tasted in Moscow means an imminent visit to the ballet, lurking around some ridiculously icy corner. And endless dishes of potatoes. And Chekhov. Don’t even get me started on Chekhov. Anton, the Darling of the Criminally Depressed and the Champion of Suicidally Dull Birds.”

“Here’s to Anton! na zdarovye, everyone!”

More of the iced firewater thawed any remaining inhibitions. The waiters turned a blind eye to the mild anti-Russianisms around the table (for they themselves were there in Sarajevo for a good reason, and it was not the love of their motherland).

The maître d’ and his tuxedoed crew had started to resemble a cape of vampires. As more vodka was ordered, they gathered at the exits of the large, ancient banqueting hall, now serving only the diplomats’ table. Each had the obligatory widow’s peak and a stare that concentrated somewhere through the eyes and fifty feet beyond the skull of the person he was addressing. Any one of them could have been two hundred and fifty years old while appearing to be fifty. They served everything with a worrying lack of garlic and generous helpings of gloopy Romanian Cabernets. The maître d’ had them all under his control, though his well-practiced misogynist focus was on Lorelei. And to hell with tradition. If, back in the land of his forefathers, the Mad Monk Rasputin could have made passionate, unholy, and hairy love to his queen, and in turn, his queen, Catherine, reputedly died under the weight of an eager, yet somewhat intrigued, copulating stallion, then certainly this beauty might grace his tables and imbibe his vodka. The clear liquid reappeared from an inexhaustible source behind the bloodred curtains.

Srna’s imaginings were elsewhere. Why had Prince Albert done THAT to himself? he thought.

* * *

The fuel from the fine vodka had led the foursome out of the clutches of the polite vampires and into a den of vice. The Cellar sat three meandering city blocks away, and down a side street.

There they took their place around a circular table and ordered overpriced champagne. The conversation swayed pendulously between world politics and a cheaper form of prostitution—the one on offer not twenty feet away. The Cellar also hosted a shockingly untalented, overmaquillaged French cabaret chanteuse, called Dorithe, who croaked a ghastly libretto. According to Herb, her tone resembled that of a goose farting in the fog.

* * *

Meanwhile, more absinthe was firing up the boys as they headed back toward the palace. The streets were quiet.

They pondered the wisdom of their trek to the Old Sultan’s.

“I know! Follow me.” Johan pulled his friend to the left, away from the empty boulevard.

* * *

A fine and fragrant lady of the night muscled in between the twins and whispered in Herb’s ear. He looked interested.

A burst of laughter echoed as Srna gave them all his best impression of the perpetually furious, energetically uncomfortable, and supremely crazy Indian diplomat from Vienna, Mr. Rajee. It was his party piece. It was a good one.

* * *

The door opened. The boys entered the Cellar.

There, at the first table they were set to walk past, were three smartly dressed, drunk men and a girl whom Johan recognized, her pupils as black as the Earl of Hell’s riding boots.

Oh God! Concentrate! Johan, concentrate!

Johan moved directly toward the table from where the laughter came.

Aphrodite had surely seen him.

Five

We Are the Music Makers. We Are the Dreamers of Dreams.

Oh! Pleasant exercise of hope and joy!

For mighty were the auxiliars which then stood

Upon our side, we who were strong in love!

Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,

But to be young was very heaven!

—William Wordsworth

Early hours June 10, 1913. Sarajevo.