Полная версия

The Invitation: Escape with this epic, page-turning summer holiday read

Afterwards, he goes to pour them each another drink. She lies in the bed and watches him, the sheets pulled up about her. He brings the glasses back to her, and they drink in silence for a few minutes. He wonders if she, like him, has suddenly been reminded of the strangeness of the situation, of the fact that they know nothing about one another.

‘Is that where you write?’

He follows her gaze to the makeshift desk, the typewriter, and realizes that what she must be seeing is a romantic image – a false one. He drains the glass, feels it burn through the centre of him. And perhaps it is the work of the whisky, perhaps it is his knowledge that they may never meet again, but he feels a sudden compelling need for honesty. ‘I have a confession. I’m not a writer. I thought I was, once.’ She has turned her head on the pillow to look at him. He coughs, continues. ‘I had a collection of short stories published. Not in a big way, you know – but it was something.’

In 1938, just out of university. It was a very small press, and the print run had been a few hundred copies. And yet, nevertheless, here it was: him, a published author, at the age of twenty-one. The sole review had been good if not absolutely effusive. That was enough. There was time for improvement. He had his whole life ahead of him. His mother had been overjoyed. His father, a Brigadier, a hero of the Great War, had been … what? A little bemused. All well and good for Hal to have this hobby before doing the thing, the real job, that would mark him out as a man. Hal knew, though, that this was the thing he wanted to do for ever. He feared it, because he wanted it so badly.

‘I’ve lost it now,’ he says. ‘I can’t do it any longer.’

There is no answer at first, and he wonders if she might have fallen asleep. But then she says, ‘What happened?’

‘The war,’ he says, because it is an accepted cliché these days – and also partially true.

It was something that had changed, in him. Every time he tried to write he felt the words coloured by this change, as though it infected everything. As though it could be read in every sentence: this man is a coward; is a fraud.

He won’t see her again. ‘Someone died,’ he says, ‘a friend. He wrote, too. After that, I haven’t felt like I deserved to be doing it … not when he never will.’ The liberation, of saying it aloud.

She doesn’t ask for him to explain further, and he is relieved, because he feels only a hair’s breadth away from telling her the whole thing, which he might regret.

‘You won’t have lost it. Once you’re a writer, it’s in you, somewhere.’

‘What makes you say that?’

‘My father was one.’

‘Would I have heard of him?’

‘No,’ she says. ‘No. I don’t think so.’

‘Tell me about him.’ But no answer comes, and when he looks down at her, he sees that her eyes are closed.

2

That morning, watching her readying herself to leave, his body had been alive with remembered sensation. In the unforgiving early light he had seen with some surprise that she was a little older than he had thought: several years his senior, perhaps.

She was pale, anxious, altered. She had hardly looked at him, even when he spoke to her, asked her if he could get her anything, walk her to her hotel. When she had sat and rolled on her stockings she had ripped the heel of one in her haste to be dressed and gone.

The last thing she had said before she left was: ‘You won’t …’

‘What?’

‘You won’t tell anyone about this?’

‘No. Will you?’

‘No.’ She had said it with some force, and he had wondered if he should be offended.

Then she had left, and his apartment had become once again the small, untidy, unremarkable place it had been before. He had lain in the tangled sheets, with the warmth of the new memory upon his skin.

She will be back in America now, no doubt. Undoubtedly she is no longer in Rome. But he keeps imagining he sees her. Through a café window, in the Borghese gardens, buying groceries at the Campo de’ Fiori market.

Those few whispered sentences, in the moments before sleep, had been the frankest conversation he could remember having with anyone in a long time. Perhaps since before the war. That had been one of the problems, with Suze. Every time he had tried to talk she had seemed so uneasy, or, worse, bored – that he hadn’t wanted to say any more. So he’d never managed to tell her about what he had done; about his guilt. Perhaps she had guessed that there was something she wouldn’t want to know, and this was why she had been so resistant to being told. She had wanted to see him, as everyone did, as the returned hero. If you had returned alive, whole, you had had a Good War; you were heroic. This thing he wanted to tell her would not fit with that image.

Stella: he realizes he never even found out her last name. Yet he doubts that she would have told him, had he asked. It was all part of it, the sense that she was holding some vital part of herself back. It had intrigued him, this reticence, because he recognized it in himself. And then, in bed, she had briefly come apart, and he thought he had caught a glimpse of that hidden person.

He would like to talk to her again, to see her once more. But no doubt the peculiar magic of it had been due to them being strangers.

He can’t even remember her face. Had she been so beautiful as all that? Usually, he has a good recall of detail. He can recall what she had been wearing, but when he thinks of her face, the impression he is left with is like the after- effect of staring too long at a lamp.

There is one thing, though, one inarguable fact. For the first time in years – years of insomnia or fitful, disturbed sleep – he had a full night’s rest, and did not dream.

He learns that the Contessa has got the funding for her picture. Fede tells him it is some American industrialist, keen to cloak himself in culture perhaps. Filming has apparently already begun, somewhere on the coast, and in a studio near Rome. Not Cinecittà, though, but a tiny set-up owned by the Contessa herself. An interesting name: il Mondo Illuminato. The Illuminated World.

On a whim, he takes a detour one morning past the building that had housed the party. But the whole place is shut up, looking almost as though it has remained thus for the last five hundred years. Perhaps he should not be surprised. The whole night had felt hardly real.

3

March 1953

An early spring day, almost warm. He walks to work along the river, squinting against the light that flashes off the water. The city looks as glorious as he has ever seen it, wreathed in gold, and yet as ever he feels as if he is looking at it through a pane of glass; one step removed. Perhaps it is time to move again, he thinks. Perhaps he should have gone further afield in the first place: out of Europe. America. Australia. Money, though: that is a problem. North Africa could be more feasible. Somewhere out of the way, where he might live on very little and make a last attempt at the wretched writing. The war novel: the one meant to make some sense of it all. The problem, he thinks, is that one has to have made sense of something in one’s own mind before committing it to paper.

As soon as he enters the office, he is stopped by Arlo, the post boy.

‘A woman called, and asked for you.’

‘She did? What was her name?’

‘Um.’ Arlo checks the note. ‘No name.’ And then defensively, ‘She said she was a friend – I didn’t think to ask.’

‘Where is she?’

‘She’s staying at a hotel …’ Arlo searches for the name, raises his eyebrows when he finds it. ‘The Hassler.’

He wonders. It could be her, he thinks. He cannot think of anyone else he knows who could afford to stay at the Hassler, after all. He feels a thrill of something like anticipation.

‘This way, sir.’

Hal follows the man into the drawing room. His first thought is that it is precisely the sort of atmosphere his father, the Brigadier, would be drawn to. It reminds him powerfully, in fact, of the Cavalry and Guards club, where his father would stay while in London. From the windows the Spanish Steps are visible, thronged with life. The room is not crowded, but he searches in vain for a glimpse of blonde.

The waiter is leading him now toward a table in the opposite corner. When he sees its occupant, seated with her back to him, Hal is about to tell the man that he has made a mistake. This cannot be the person he is meeting. But then she turns.

‘Ah,’ she smiles, and raises one eyebrow. ‘You came, I’m so pleased. I did not know if you would be interested in keeping an appointment you were actually invited to.’

‘Contessa.’ He takes the seat opposite her.

‘I thought I would keep my invitation mysterious enough to intrigue you.’

‘It certainly did.’

‘You guessed that it came from me?’

‘Ah – no, I did not.’

She peers at him, and smiles. ‘You hoped that it was someone else?’

‘Not at all.’

‘Well,’ she says. ‘I have an offer of work for you.’

‘You do?’

Her smile broadens. ‘Ah, but you’re interested now!’

‘What is it, exactly?’ As if he is in a position to turn down anything. But he did not live with his father for so many years without learning something of how to conduct business.

Before she can speak the waiter has appeared to take their order.

‘Bring us some of that gnocchi,’ she tells him. ‘The one that Alessandro makes for me.’

The man nods, and disappears.

‘So,’ she says. ‘To business.’

‘Of course.’

‘My film, The Sea Captain, is being released this spring.’

‘Congratulations – I heard that you had funding for it. I didn’t realize it was finished.’

‘Thank you.’

The gnocchi arrives now. Hal has only eaten the dish alla Romana – doughy shapes submerged in sauce and baked. These are delicate morsels, scattered with oil and thin leaves of shaved truffle. They are delicious – and Hal notices that the Contessa, despite her extreme slenderness, is enjoying them with the same relish as he.

‘Who directed the film?’ Hal asks.

The Contessa smiles. ‘Giacomo Gaspari.’

‘Goodness.’ Hal is impressed. ‘It must be something.’

She nods and says, without preamble, ‘It is. Quite brilliant – which I can say, because I’m not the one responsible for that. It will be screening at the festival, at Cannes.’

‘That’s wonderful.’

‘I hoped that you might come with us.’

‘To Cannes?’

‘Yes – but on the journey there, too. I’ve planned a trip first. A tour, along the coast where it was filmed, to publicize it. And to make the people of Liguria feel that they are involved, that it is their film. It is what they do in Hollywood: why should we not do it here?’ She smiles at Hal. ‘I thought you could cover it.’

‘For The Tiber?’

‘No,’ the Contessa says, with a note of triumph. ‘For Tempo.’

Tempo is in the big league – Italy’s answer to the American Life. ‘But how? I don’t know anyone there.’

‘Ah, but I do. They asked me if I knew of a writer who would do it – and I suggested you.’

Hal can’t help asking. ‘Why?’

‘I like the way you write.’ Seeing his expression, she smiles. ‘I told you I would not forget. Luckily, the editor at Tempo agrees with me that you are the right man for the job.’

‘When?’

‘The film festival is next month. But you would be needed for the two weeks before it, too.’

‘Well,’ Hal says, trying to process it all. ‘I suppose it depends …’

‘On the fee? I’m afraid the one they’ve offered is rather small.’ She names the sum: it is still far more than The Tiber pay for an article. ‘But I thought I would help. Because you would be doing me a personal favour, too.’ She takes a fountain pen from her reticule and scribbles on the menu. She turns it towards him, and says, with genuine regret, ‘I’m sorry it can’t be higher. I have a budget, you know …’

Hal stares at it, absorbing the significance of the extra nought. With it, he could travel to one of the wild, liminal places he has been thinking of: certainly North Africa, Australia even.

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘I could do it for that.’ To do anything other than accept, considering the sum in question, would be idiocy.

‘Excellent. I will put you in touch with the man I spoke to there.’ She takes up her fountain pen again, and passes the menu back to him. There written next to the primi piatti, is an address: Il Palazzo Mezzaluna, vicino a Tellaro, Liguria. He has not been to Liguria: has only a vague idea of brightly coloured houses beside an equally luminous sea – glimpsed, perhaps, on a postcard.

‘You will need to be there,’ she says, ‘in three weeks’ time.’

‘I shall,’ he says, quickly. ‘Thank you. Thank you so much.’

The smile she gives him is enigmatic. He feels a sudden trepidation. He has learned to distrust things that seem too good to be true.

4

Liguria, April 1953

His first impressions of Liguria are snatched through a smeared train window. These are visions at once exotic and banal: washing strewn from the windows of red-tiled, green-shuttered houses, road intersections revealing a chaos of vehicles. Palm trees, tawdry-looking railway hotels. The occasional teal promise of the sea. The sea. At the first glimpse of it he finds himself gripping the seat rest, hard. Sometimes it has this effect on him.

This whole mission still has about it an air of unreality. If he hadn’t had that slightly stilted meeting with the editor at Tempo – who seemed as bemused as he did as to why he had been chosen – he might have reason to believe it was all the Contessa’s little joke.

‘Keep it light,’ the man had said. ‘What do the stars eat and drink, what do they wear? What is Giulietta Castiglione reading, ah, what does Earl Morgan do to relax? Stories of cocktails in Portofino, of sun on private beaches. Of … of a sea the colour of the sapphires our leading lady wears to supper.’ Hal had tried not to smile. ‘Nothing too worthy. Our readers want escapism. Niente di troppo difficile. Capisci?’

‘Si,’ Hal had said. ‘I understand.’

La Spezia is no great beauty, though there is a muscular impressiveness to the place, the harbour flanked with merchant vessels and passenger ferries. Not so long ago there would have been warships marshalled here. To Hal they are almost conspicuous in their absence. The enemy’s own destroyers and submarines, sliding beneath the surface black and deadly.

He catches the passenger ferry, and realizes that it is the first time he has been afloat in years. Again, he reminds himself, it is all different. The tilt and shift of the boat much more pronounced; so close to the water that he can feel the salt spray on his cheek. He concentrates on the sights. Here, finally, is the fabled beauty: the land rising smokily beyond the coast, the clouds banked white behind. A castle, rose-gold in the afternoon sun.

He looks at his fellow travellers. Poverty still pinches some faces tight, clothes are a decade or more out of date. Marshall Aid, it seems, has not lessened the struggle by much for them. In the relative prosperity of the capital it is easy to forget – to feel, sometimes, like a poor relation.

At Lerici, a little way down the coast, all the passengers disembark. Hal hasn’t yet worked out this part of the journey, but according to the map the place should be only a few miles by water. Hal goes to the skipper, who lounges against the stern with a cigarette and scowls at him through the smoke.

‘Il Palazzo Mezzaluna?’

The man takes a lazy drag, squinting as though he hasn’t understood. Hal repeats himself. As comprehension dawns, his question is met with a short, derisive bark of a laugh, a shake of the head.

‘No,’ the man says. ‘It isn’t on my route. It is a private residence.’

‘Yes,’ Hal says. ‘But for a little extra?’

‘No, signor. I am finished for the day.’ But as Hal turns to leave him he shouts something, gesturing to several small crafts heaped with fishing gear. A group of sunburned men sit near them, sharing an impromptu picnic of bread and shellfish, shucking them with their knives and sucking the morsels from the shells.

Hal approaches them and asks his question. One of the men shrugs and stands, brushing breadcrumbs from himself. He leads the way over to his boat and moves a few items around – nets, a can of oil, a box of bait and a rod – to make room for Hal and his bag. Hal clambers in, aware of the ambivalent gaze of the men who remain, eating their oysters. What do they make of him, this Englishman in his tired suit, climbing in beside the fishing tackle?

The man starts his engine and they putter out of the harbour, pitching dangerously as they cross the wake of a larger boat. Then back out into the navy blue of the open sea, rounding the nub of the headland. The little boat speeds across the water, sending up a fine salt spray. After only fifteen minutes or so the man points to the shore.

‘È là!’

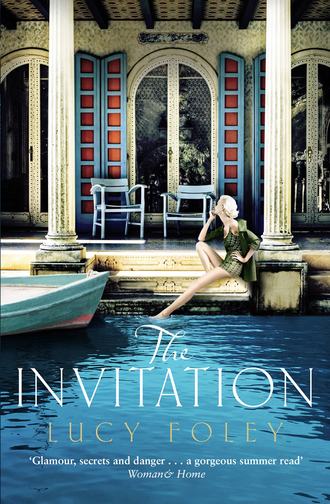

In the distance: a semicircular opening in the dark mass of trees, separated from the water by a silvery thread of sand. And nestling among the trees, dead centre, an enormous building. A grand hotel, one might presume, seeing it from afar. As they draw closer Hal is better able to make it out. A palace, in the Belle Époque style. The façade is a coral pink that anywhere else in the world would look ridiculous … and yet here, drenched in the evening sun, is something like magnificent. A white jetty stretches out like a piece of bleached driftwood into the blue depths. A figure waits, watching their approach.

Hal steps onto the jetty, heaving his bag after him. The waiting figure is a liveried member of staff who strides toward Hal, hand outstretched for his luggage. Against the spotless white of his uniform the leather case looks small and battered.

‘Good evening, sir.’

Hal goes back to the fisherman, pays him, quickly. The man seems a little bemused, as though he had never expected his shabby passenger to be welcome in such a place. With a shake of his head, as though to clear it, he fires his engine and is gone.

It is evening now, Hal realizes, the light like blue glass. Before them rises a shallow stone staircase flanked by a line of pine trees. Each is topped by a fluid dark abstract of foliage, like a child’s drawing of a cloud. Their resiny scent fills the warm air. The man leads the way, moving so briskly that Hal has to jog a little to keep up. They move past a series of gardens, each, Hal sees, is different from the last. ‘The Japanese garden,’ the man says, as they pass the first: and in the manmade pools Hal glimpses an iridescent carp, sliding fatly among trailing pondweed. There are ornamental bridges, gravel raked into intricate patterns about carefully shaped hillocks of moss. Then the Moroccan garden, filled with bright blooms that spill from urns painted a luminous blue. The Italian garden: a stately formal arrangement of dark shrubs and classical statues. As Hal and his guide pass, a flock of white doves take wing. It is itself like a film set, Hal thinks, hardly real.

Inside, the house is a cool space, reminiscent of an art gallery. A couple of line drawings that might be Picasso – his eye isn’t good enough at this distance to be certain. A cuboid nude that could be Henry Moore.

The room that he is shown to is white, high-ceilinged.

‘You can change here for the evening,’ the man tells him. ‘Drinks are at seven thirty.’ Hal looks down at his travelling suit. Change into what, exactly? The suit is crumpled, but it is by far the smartest thing he owns. He wore it because it is the smartest thing he owns. And so he sits down on the bed, looks about himself. The window has a view out towards the back of the house, where a great stone terrace leads down into further manicured gardens, showing now as a dark emerald green. A space hewn by the twin forces of wealth and will out of the natural gorse. At the far end is a line of tall cypresses. In the weakening light they are black sentinels, funereal in aspect. Suddenly he catches a shimmer of gold, which resolves itself into the hair of a woman. She wears what appears to be a long black dress, camouflaged against the trees behind her so that only her face and arms can be made out. An unnameable excitement runs through him. He goes to turn out the light in the room, so he can make the scene out better, but when he looks back she has disappeared.

At eight o’clock the open window discloses the unmistakable sounds of musical instruments being tuned: the squawk of violins, the throb of a double bass. Hal showers in the gilded bathroom, sloughing off the crust of salt, and glances quickly in the mirror. His clothes are more creased than ever. But his face betrays little of his tiredness. He knows that he is lucky, to look like this. His face is his passport.

When he returns downstairs the gardens have been transformed: lit now by a host of lanterns and filled with guests. Some of the guests are from a similar crowd to the party in Rome; they have that same lustre of wealth, of lives lived on the grand scale. But he sees, too, children dressed as if for the beach, dark-haired girls in simple sundresses, men in casual trousers and unbuttoned shirts. Along one wall of the house a line of elderly men sit and talk with great intensity: all wear battered caps in various sun-faded hues, sandals on hoary feet. The women who Hal presumes are their wives look on censoriously from a few metres away and they, too, wear an unofficial uniform: floral-patterned smocks and woollen cardigans. Hal’s suit no longer seems such a faux pas. But he is aware that he belongs to neither tribe: not that of the dinner jackets, or that of the summer slacks. He is an anomaly.

‘Hal.’

He turns, and finds the Contessa. She is wearing a tangerine linen dress than could almost be a monk’s tabard, with a large hood pulled up over her hair. It is one of the more eccentric outfits Hal has ever seen.

‘I’m so pleased,’ she says. ‘I worried that you would change your mind.’

Hal thinks that she can have no concept of a journalist’s living, if she imagined he might have been able to turn her offer down.

‘I wanted to know something,’ he says, because he has been wondering. ‘How are we travelling to Cannes?’

‘Ah,’ she says, ‘but you will find out tomorrow morning.’

‘All these people are coming too?’ He gestures toward the crowd.

She laughs. ‘Oh, no. No. I have invited them all for the evening.’ She counts off the different groups on her fingers. ‘There are friends, the film crowd, your colleagues from the press’ – she gestures towards a passing photographer – ‘and some of the people from the village near here. They come often – especially the children and their parents – to swim off my jetty, and walk in the grounds. It is why I make such an effort with the gardens. And they appreciate a good party, like all sensible Italians. Wait until the dancing starts. But first I will introduce you to the other guests. Come.’ She beckons with one hand.

The man she leads him to first is etiolated-looking, with blond hair so pale that it is almost white, receding on either side of the head severely. A thin face, with all of the bones visible beneath the skin. He is dressed in a wine-coloured suit – beautifully made, but with the unfortunate effect of making his complexion sallower still.

The Contessa moves into English. It is the first time Hal has heard her use it, and he is surprised by her fluency. ‘Hal Jacobs, meet Aubrey Boyd, who will be taking the pictures to accompany your article. This man is the only true challenger to Beaton’s crown, in my opinion. He is a simply splendid photographer – makes one look like a goddess. He has a way of making all one’s little wrinkles disappear. How do you do it?’ The Contessa is impressively wrinkled even for one of her advanced years. A life well-lived, Hal thinks, much of it in the full glare of the sun.