Полная версия

Thriller 2: Stories You Just Can't Put Down

“Doesn’t ring a…”

I could tell the exact moment that bell began to ring. His stare froze, his mouth half opened and his expression went from seductive to panic in the blink of an eye. “Don’t think I know her, sorry.”

In less than a heartbeat, my trusty little friend was pressed up against his temple.

“Should I describe her to you, Daniel? Should I remind you of the last time you saw her?” I had straightened up and now had him backed up against his front fender.

He was silent, trying frantically, I believe, to find a way out of this, a way to disarm me. He wanted to grab for the gun, I could see that in his eyes, but he wasn’t sure of my strength or my reflexes, so he, like a wolf, was gauging my movements, biding his time when he could move in for the kill. He opened his mouth to speak, thinking to distract me.

“Don’t say a word I don’t ask you to say,” I hissed, jamming the gun into the flesh on the side of his face. “I’m going to ask you a question, and you are going to answer it. No bullshit, understand? One question, one answer, or I will shoot you now, right now.”

Sweat beaded on his forehead, and I was certain he understood.

“The name of the others who were with you when Jessie Fielding was raped.”

“I don’t know…”

“You weren’t listening, Daniel. I will repeat this only one more time. I ask a question, you give me an answer, or I do you right now.” I was beginning to sweat a bit myself. I wanted this over with. “One last chance, Daniel. Who was with you when Jessie was raped?”

“Some of the guys, I didn’t know.”

“Then some of them, you did. Give me a name.” I began counting backward from ten.

When I got to six, he said, “Antonio. Antonio Jackson.”

“Is he from around here?”

Sweating profusely now, he nodded. “He’s my cousin.”

“Where can I find him?”

“He lives over on Chester Avenue.”

“Thank you, Daniel.” I smiled, and for a moment, he seemed to relax.

Then I pulled the trigger.

I watched his body jerk, then slide sideways onto the ground. Then, satisfied, I walked into the shadows and through the alley that took me, eventually, to my car parked two blocks away.

I heard the sirens as I started my engine. A few minutes later, I pulled to the side of the road to allow the speeding patrol car to pass me.

That night, I slept straight through until morning for the first time since the night that changed everything.

“One down, Jessie,” I whispered in her ear the next night. “Daniel Montoya. One down…”

I left her sitting in her wheelchair, her eyes still trained on something beyond the window that no one else could see.

There’d been no change in her expression, but I know she’d heard and understood exactly what I said.

Ten days later, in the parking lot of yet another bar, Antonio Jackson and I came face-to-face. It had been remarkably easy to get his attention. Anytime a tall, well-built blonde beckoned, men like Jackson lost all caution. Even after what had happened to his cousin Daniel, Antonio apparently never considered the danger once he saw me perched on the hood of his car, my long bare legs dangling off to one side.

“One name,” I told him. “Just give me one name.”

He’d hemmed and hawed as I pressed the barrel of the gun to his throat. He stalled and he pleaded and he cried, but in the end, he gave me the one thing I wanted from him.

“Eddie Taylor.”

“Thank you, Antonio.” I pulled the trigger, and he dropped like a stone.

“Antonio Jackson,” I told Jessie the next evening. “Two down.”

It took me almost three weeks to find Eddie Taylor because he’d been in the county jail for possession and had only been back on the streets for less than forty-eight hours when we finally met. Like an avenging angel, I stepped out from the alley as he walked in. I knew I had the right guy. I’d spent every one of those twenty days staring at his picture on my computer.

“One name,” I’d said, emboldened by my previous success. “That’s all I want from you, Eddie. Just give me the name of one of the other guys.”

He’d swallowed hard and tears streamed down his face.

“Awwwwww,” I mocked him. “Scared, Eddie? Did Jessie cry when she realized what you were going to do to her? Did she cry when you raped her?”

“Listen, let me…”

“One name, Eddie.” When he didn’t respond, I once again started counting backward from ten. I’d found that to be universally understood.

“Kelvin Anderson.”

“Thank you, Eddie.” I shot him through the heart.

“Three down,” I told Jessie the next night. “Eddie Taylor…”

Obviously, the police were not oblivious to the fact that several young men from the same general neighborhood had been taken out by the same shooter—hello, same gun, which thank God wasn’t registered anywhere, I’d been careful in that regard even while I may have seemed careless in others—but they didn’t seem overly interested in investigating too deeply. After all, at one time or another, they’d arrested Daniel, Antonio and Eddie. I began to think of myself as performing a public service when I realized that the rap sheets of the three of them would have reached halfway to Pittsburgh. In my own way, I was proud of myself. I was taking the steps necessary to ensure that no one would ever go through what Jessie’d endured. As for my conscience, well, after the night that changed everything, do you seriously think my conscience bothered me over ridding the world of a couple of predators?

A month later I found Kelvin Anderson, and he kindly supplied me with the name of yet another wolf. Frankie Eden and I had a tête-à-tête in the front seat of his car, and later that same night I was able to confirm to Jessie that the count was now four down, and two to go.

Frankie Eden’s eyes told me he knew who I was, why I was there and where his next stop through the cosmos was going to be. He gave up the last two without flinching, and of all of them, I have to say that Frankie was the only one who died like a man.

Bernie Gunther and Dominic Large weren’t as easy to track down, but in the end, although it took several months, I’d eliminated every one of them.

After I’d taken out the last of the six—that would have been Bernie—I went back to my apartment and took a long, hot shower. I slept straight through until one the following afternoon, which barely gave me enough time to do what I knew I had to do before evening came. After I’d completed my errands, I took another shower and blew out my hair so that it hung in long soft waves over my shoulders and down my back. I hadn’t realized it had gotten so long. I’d been so focused on the task I’d set for myself that I’d barely looked at my reflection in the mirror anymore. I was surprised to see how gaunt I looked, how pale and thin I’d become, which had, I suppose, prompted all those questions at work I’d been brushing off.

“How are you? Are you feeling all right?”

“Have you been ill?”

Yes, I’ve been ill, I wanted to say. Sick to death of myself, I wanted to say.

“No, I’m fine. Really.” I’d smile and make an effort to put a little spring back into my step.

But soon—probably by this time tomorrow, I thought—everyone will know the nature of my malady.

I typed up the letter I’d composed, sealed it and walked the seven blocks to the home of my parents. My father would still be at work; my mother had gone in to the city to have lunch with some friends and would have spent the rest of the afternoon shopping. I owed them the truth—they deserved the truth—but ever the coward, I was grateful to God that I wouldn’t be around to hear what any of them would have to say. I could not have borne my mother’s look of shock and horror, my father’s cold stare of disbelief and disappointment.

I walked back home, feeling just that much lighter that at least in this, I’d done the right thing. I needed to make certain that neither of my parents would think that in anyway, this was their fault, that they’d failed me in some way. I needed them to understand that the guilt, the shame, the failure, was all mine.

I loaded the handgun and tucked it into my bag. I looked around my apartment for the last time, my gaze lingering on those possessions that had once meant so much to me. The antique tables my grandmother had given me, the sofa I’d saved so long to buy, the candlesticks my mom had given me when I moved in. They’d been a wedding gift from an old friend of hers, and she’d never used them. Neither had I.

I sighed and closed the apartment door for the last time. Looking at the lovely millwork that surrounded it, I decided to leave the door unlocked so that when they came to search my place, they wouldn’t have to damage anything to get inside.

The drive to the nursing home seemed endless that night. For the first time ever, every light I approached turned red, as if some cosmic something was telling me to stop. But it was far too late for that. I’d done what I had to do, and now I was going to let Jessie do what she needed to do. I passed an old cemetery and thought for the first time about where they’d lay me to rest. Would I be permitted to be buried in the family plot once they learned what I’d done? Again, the only emotion I really felt was gratitude that I would not have to face their horrified eyes when the truth came out.

It was still early evening when I arrived at the nursing home, so I parked my car near the butterfly garden that some local school kids had planted for the residents and turned off the engine. Knowing I would not be needing them again, I left the keys under the driver’s seat and sat quietly for a few moments, taking deep breaths and holding them for as long as I could to calm myself. After my nerves steadied, I got out of the car, taking my bag with its special cargo with me. I took the long way to the building, going through the garden and soaking up the scents and the colors. Did one’s sensory memories go with them to the afterlife? I wondered.

I went up the handicapped ramp because it took me past the birdbath where, not surprisingly for that hour, no birds were bathing, but the little fountain there still trickled water and I loved the sound. I went through the big double doors in the front of the building in an effort to hold on to the music of the fountain for as long as I could.

Walking past the guard, I smiled and waved. They were all used to seeing me now, and so there were no questions asked while I signed in. Everyone knew me as Jessie’s devoted friend. I headed toward the south wing and Jessie’s room, trying to conjure up the words to “Don’t Fear the Reaper,” which, to tell you the truth, I didn’t. For me, dying wasn’t nearly as bad as living with what I’d done and what I was.

I went into Jessie’s room and found her sitting in a chair near the window, her untouched dinner tray on the foot of the bed. I knew how she felt. There were times when the horror of the night that changed everything came back full force and filled me so that the thought of eating made me physically sick.

“Jessie,” I said, seating myself on the chair opposite hers, “it’s done now. They’re all gone. All six.”

I opened my bag and felt the butt end of the old handgun, all cool metal hardness. My fingers wrapped around the handle and I drew it out.

“I know you’ve wanted to do this since the night it happened.” I took her hands and placed the gun in them. “It’s all right,” I told her. “I deserve this. Everyone will know the truth now. No one will blame you. And after it’s done, you can come back, Jessie. You can come back into the world, once I’m gone from it.”

I sat directly in front of her, my back straight, my vision clear, my conscience for once subdued. I was ready.

Jessie’s gaze dropped to the gun in her hand and she stared at it for a long time before looking up at me again. The gun raised slowly, the barrel aimed at nothing in particular. I tapped my chest, right where I felt my heart beating, with my index finger and told her, “Aim here. I’m ready when you are.”

I closed my eyes, and waited for the end to come. And waited.

Curious, I opened my eyes just as swiftly, so swiftly, before I could take a breath or utter a sound or reach out to stop her, Jessie’s wrists twisted and suddenly the gun was at her temple, and the room reverberated with the single shot.

I stared in horror as Jessie slumped forward before falling face-first from the chair onto the floor, red like a fluid carpet flowed around her as if to cushion her fall.

“No!” I screamed as the room filled with people.

Suddenly nurses, orderlies, visitors, residents, everyone who’d been close enough to have heard the shot crowded into the room even before the realization of what she’d done completely sunk in.

“Oh, my God, Jessie,” one of the nurses said, “what have you done…?”

What, indeed?

So there I was…obviously I’d brought her the gun with which she’d killed herself, which made me an accessory.

My panicked brain recognized immediately that one, I was not dead, and two, I’d be charged with a crime. But since I was alive, and Jessie was not, at that point, copping to a charge of accessory to murder was definitely more appealing than admitting what I’d really done.

The story I’d tell swirled through my head, bits and pieces tripping over each other as I tried frantically to put one together. And I’d come up with a pretty damned good one, if I do say so myself.

Jessie couldn’t face another day living with the memory of what had happened to her. She begged me—begged me—to help her to end it. As her friend, as someone who loved her, as the only person to whom she’d speak, how could I deny her that release? Who would doubt that story, knowing what she’d gone through?

I could get off with a light sentence, I knew, once I explained. No one would ever need to know the truth, right?

I was just starting to breathe a little easier when the door opened and my father walked in. He’d seen the story on TV—who in the tristate area had not?—and he’d come down to the station.

But he’d not come to comfort me, or even to ask me why.

His gaze was just as cold as it had been when, as a child, I’d disappointed him in some fashion. I wasn’t surprised, frankly, that there’d be no attempt at understanding. There never had been in the past.

In his hands, he held a blue envelope. The same blue envelope I’d left in his mailbox earlier.

“Daddy,” I said, ever the coward, holding out my shaking hands, silently pleading for him to give it to me.

But Judge Lucas Bradley—Judge Luke “Hang ‘Em High” Bradley—handed the letter over to you. I guess there were other instincts that were stronger in him, other bonds harder to break than the one that existed between father and daughter.

Signed this date: Deanna Jean Bradley

When Detective Mallory Russo finished reading the last page of the statement, she held it up in one hand and said, “You haven’t signed it.”

“I will.” The young woman held out her hand for the pen.

The detective and the once promising assistant district attorney stared at each other from across the table.

“You could have come to me, Dee,” Mallory told her. “You could have given me the information and we could have gone after these guys. It didn’t have to be this way.”

“Yes, it did, Mallory. And may I remind you that none of you were too interested in them even as I was picking them off.” The A.D.A. shifted in her seat. “Besides, everything that happened…it was all my fault. It wasn’t your fight.”

“They’re all my fights,” Mallory told her. “We’ve known each other for years, Dee. Why couldn’t you have trusted me to take them down?”

Deanna shrugged, her eyes shifting to the two-way window on the opposite side of the room.

“Is he still there, watching? My father?”

“Judge Bradley left an hour ago.” Mallory rested her arms on the table.

“You know, he could have burned my letter, he could have kept it and held it over my head for the rest of my life.” Deanna Bradley continued to stare at the mirror. “I still can’t believe he turned against me.”

“Your father has an unswerving sense of justice,” Mallory reminded her. “He’s always going to follow his conscience.”

“So will I, Mal.” Deanna sighed. “So will I…”

Chapter Nine

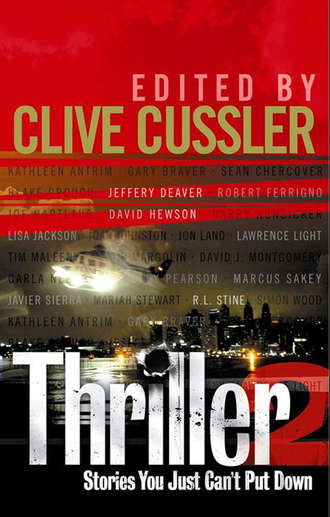

David Hewson

David Hewson knows where to find the perfect black rice in Barcelona, the richest coffee in Venice and how to kill a person in a thousand gruesome ways. His wonderful series set in Rome, featuring detective Nic Costa and his stand-alone thrillers share an authentic sense of place, characters with rich lives that began long before you picked up the book and a relentless sense of pacing that pulls you into their world.

“The Circle” is a perfectly symmetrical tale that shatters our comfortable isolation from current events. Through the eyes of a young pregnant woman we see the world from a new perspective as a train carries her from a state of innocence into a state of fear. Hold on tight, because like it or not, every one of us is already along for the ride.

Chapter Ten

The Circle

The Tube line ran unseen beneath the bleak, unfeeling city, around and around, day and night, year after year. Under the wealthy mansions of Kensington the snaking track rattled, through cuttings and tunnels, to the bustling mainline stations of Paddington, Euston and King’s Cross, where millions came and left London daily, invisible to those below the earth. Then the trains traveled on to the poorer parts in the east, Aldgate, with its tenements and teeming immigrant populations, until the rails turned abruptly, as if they could take the poverty no more, and longed to return to the prosperous west, to civilization and safety, before the perpetual loop began again.

The Circle. Melanie Darma had traveled this way so often she sometimes imagined she was a part of it herself.

Today she felt tired. Her head hurt as she slumped on the worn, grubby seat in the noisy, rattling carriage, watching the station lights flash by, the faces of the travelers come and go. Tower Hill, Monument, Cannon Street, Mansion House…Somewhere to the south ran the thick, murky waters of the Thames. She remembered sitting next to her father as a child, bewildered in a shaking train from Charing Cross to Waterloo, a stretch that ran deep beneath the old, gray river. Joking, he’d persuaded her to press her nose to the grimy windows to look for passing fish, swimming in the blackness flashing by. On another occasion, when he was still as new to the city as she was, in thrall to its excitement and possibilities, they’d both got out at the station called Temple, hoping to see something magical and holy, finding nothing but surly commuters and tangles of angry traffic belching smoke.

This was the city, a thronging, anonymous world of broken promises. People, millions of them, whatever the time of day. Lately, with her new condition, they would watch on the train as she moved heavily, clutching the swelling bundle in her belly. Most would stand aside and give her a seat. A few would smile, mothers mostly, she thought. Some, men in business suits, people from the City, stared away as if the obvious extent of her state, and the apparent nearness of her release from it, amounted to some kind of embarrassment to be avoided. She could almost hear them praying…if it’s to happen please, God, let it not be this instant, when I’ve a meeting scheduled, a drink planned, an assignation with a lover. Anytime but now.

She sat the way she had learned over the previous months: both hands curved protectively around the bump in her fawn summer coat, which was a little heavy for the weather, bought cheaply at a street market to encompass her temporary bulk. Her fingers felt comfortable there nevertheless. It was as if this was what they were made for.

So much of her life seemed to have been passed in these tunnels, going to and fro. She felt she could fix her position on the Circle’s endless loop by the smell of the passengers as they entered the carriage: sweet, cloying perfume in the affluent west, the sweat of workmen around King’s Cross, the fragrant, sometimes acrid odor of the Indians and Pakistanis from the sprawling, struggling ethic communities of the east. Once she’d visited the museum in Covent Garden to try to understand this hidden jugular that kept the city alive, uncertainly at times, as its age and frailty began to show. Melanie Darma had gazed at the pictures of imperious Victorian men in top hats and women in crinoline dresses, all waiting patiently in neat lines for miniature trains with squat smokestacks and smiling crews. It was the first underground railway ever built, part of a lost and entirely dissimilar age.

When the London bombers struck in 2005 they chose the Circle Line as their principal target, through accident, she thought, not from any conscious attempt to strike at history. Fourteen people died in two separate explosions. The entire system was closed for almost a month, forcing her to take buses, watching those around her nervously, glancing at anyone with dark skin and a backpack, wondering.

She might have been on one of those two carriages had it not been for her father’s terminal sickness, a cruel cancerous death eked out on a hard, cheap bed in some cold public ward, one more body to be rudely nursed toward its end by a society that no longer seemed to care. Birth, death, illness, accident…Sudden, fleeting joy, insidious, lasting tragedy…All these things lay in wait on the journey that was life, with ambushes, large and small, waiting hidden in the wings.

Sometimes, as she sat on the train rattling through the black snaking hole in the dank London earth, she imagined herself falling forward in some precipitous, headlong descent toward an unknown, endless abyss. Did the women in billowing crinoline dresses ever feel the same way? She doubted it. This was a modern affliction. It had a modern cure, too. Work, necessity, the daily need to earn sufficient money to pay the rent for another month, praying the agency would find her some other temporary berth once the present ran out.

There were two more stops before Westminster, the station she had come to know so well, set in the shadow of Big Ben and the grandiose, imposing silhouette of the Houses of Parliament. The train crashed into the darkness of the tunnel ahead. The carriage shook so wildly the lights flickered and then disappeared altogether. The movement and the sudden black, gloom conspired to make the weight of her stomach seem so noticeable, such a part of her, she believed she felt a slow, sluggish movement inside, as if something were waking. The fear that thought prompted dispatched a swift, guilty shock of apprehension through her mind. The thought: this is real and will happen, however much you may wish to avoid it.

Finally the rolling, careering carriage reconnected with whatever source of energy gave it light. The carriage stabilized, the bulbs flickered back to life.

On the opposite seat sat a young foreign-looking man who wore a dark polyester jacket and cheap jeans, the kind of clothes the people from Aldgate and beyond seemed to like. He had a grubby red webbed rucksack next to him, his hand on the top, a possessive gesture, though there was no one there who could possibly covet the thing.

He stared at her, openly, frankly, with a familiarity she didn’t appreciate. His eyes were dark and deep, his face clean-shaven, smiling, attractive.

The train lurched again, the lights flashed off and on as they dashed downward once more.

The young man spoke softly as he gazed at her, and it was difficult to hear over the crash of iron against iron.

Still, she thought she knew what he said, and that was, “They will remember my name.”

She tried to focus on the book in her hands. It came from the staff library. The Palace of Westminster didn’t pay its workers well, but at least they had access to decent reading.