Полная версия

Jacked: The unauthorized behind-the-scenes story of Grand Theft Auto

With a William Buckley book tucked under his arm, Thompson entered law school at Vanderbilt University, alongside classmate Al Gore. He preferred playing golf to attending class and, despite graduating Phi Beta Kappa, flunked the bar. After moving to Miami and feeling like a failure, he accompanied a friend to a church service where everyone was dressed in shorts and T-shirts. Thompson felt at home and became born-again. Before retaking the bar, he prayed and, when he passed, took it as a sign from God to go on a crusade.

In 1987, after hearing a local shock jock on the air, Thompson hit the law books. With painstaking research, he discovered a little known fact at the time: the Federal Communications Commission had the power to regulate the airwaves for obscenity, and this station, in many ways, seemed to violate the standards. After Thompson took the unusual measure of filing a complaint with the FCC, the shock jock angrily broadcast his name and phone number. Death threats, unwanted pizza deliveries, and the local press followed, transforming Thompson into an overnight rock star of Miami’s right.

Confident, unflappable, and speedy with a sound bite, Thompson deftly played his part, faxing complaints to corporate sponsors until ads began to get pulled from the air. Despite the radio station’s legal proceedings against him, Thompson won the right in court to continue lobbying advertisers and the FCC under First Amendment protection. His hard work paid off in historic proportions when the FCC fined the shock jock’s station for indecency—the first time ever for such levies. Thompson took it as more divine purpose. “God’s people were going to be warriors with me through prayer,” he later wrote in his memoir.

Yet he already had others warring against him. Acting on the radio station’s assertion that Thompson was obsessed with pornography, the Florida bar convinced the state’s Supreme Court to determine whether Thompson was mentally ill. Faced with losing his license to practice law, Thompson underwent psychiatric testing. The test results concluded that he was “simply a lawyer and a citizen who is rationally animated by his activist Christian faith.” As Thompson later liked to joke, “I’m the only officially certified sane lawyer in the entire state of Florida.”

Empowered, Thompson assumed higher-profile battles. He took on incumbent Dade County state attorney Janet Reno for prosecutor, publicly challenging her to declare her sexuality. He made his name nationally by spearheading an obscenity conviction of rap group 2 Live Crew for their album As Nasty as They Wanna Be. With the controversy fueling demand for the record, however, the group’s leader, Luther Campbell, laughed all the way to the bank.

Thompson was on his way, though—right to Charlton Heston’s side at the shareholders meeting over “Cop Killer.” With the impossible task of following Heston onstage, Thompson warned, amid the boos of protesters, that “Time Warner is knowingly training people, especially young people, to kill. One day this company will pay a wicked price for that.”

Thompson returned to Miami for the birth of his first son, whom he and his wife named John Daniel Peace. Three weeks later, on August 24, 1992, Hurricane Andrew bore down. As his windows rattled and lightning slashed the sky, Thompson braced himself at the door in a scuba mask, holding it tight so that the glass wouldn’t blow through. His wife stood behind him holding little Johnny in a blanket. Thompson relished the biblical imagery and equated it to his own fight against what he called the “human hurricane” of rappers, pornographers, and shock jocks.

He survived the storm—and won the battle against Ice-T, who was dropped from Time Warner soon afterward. The ACLU voted Thompson one of 1992’s “Censors of the Year,” a title that made him proud. “Those on the entertainment ship were laughing at those on the other vessel,” he later wrote. “I felt that I had grabbed the wheel of the decency ship and rammed that other ship, convinced that the time for talk about how bad pop culture had become was over. It was time for consequence. . . . it was time to win this culture war.”

“COME ON, come on, come on, come on, take that, and party!”

Sam Houser stared into the smiling white faces of five clean-cut boys singing these words onstage. The group was Take That, a chart-topping boy band from Manchester, Britain’s answer to New Kids on the Block. In his new job as a video producer for BMG Entertainment, Sam was directing their full-length video, named for their debut hit, “Take That & Party.” For a kid weaned on crime flicks and hip-hop, this scene couldn’t be further from his more rebellious influences. The videos showed the boy band break-dancing, chest-bumping, and leaping from Jacuzzis. But it was a job—a creative job that fulfilled Sam’s lifelong ambition of working in the music industry.

By 1992, Sam had successfully retaken his lackluster A-Level tests and enrolled at University of London. Between classes, he headed over to intern part time at BMG’s office off the Thames on Fulham High Street. After his fateful lunch in New York, Sam had gotten his break interning in the mailroom at BMG—an accomplishment he took to heart, considering the obnoxious way he got in. Yet it epitomized his style: risking everything, including pissing people off, if it meant achieving his goals. “I got my first job by abusing senior executives at dinner tables,” he later recalled.

Sam already had his eyes elsewhere: the Internet. Though the World Wide Web had not yet become mainstream, Sam saw the opportunity to bring the kind of DIY marketing approach pioneered by Def Jam into the digital age. He convinced the BMG bosses that the best way to promote a new album by Annie Lennox was with something almost unheard of at the time, an online site. They relented, and Sam got to work. When Diva hit number one on the UK charts, it bolstered his cause.

BMG soon made waves in the industry by partnering with a small CD-ROM start-up in Los Angeles to create what the Los Angeles Times heralded as “the recording industry’s first interactive music label.” The newly formed BMG Interactive division saw the future not only in music CD-ROMs, but in a medium close to Sam’s heart, video games.

In 1994, the game industry was bringing in a record $7 billion— and on track to grow to $9 billion by 1996. Yet culturally, games were at a crossroads. Radical changes had been sweeping the industry, igniting a debate about the future of the medium and its effect on players. It started with the release of Mortal Kombat, the home version of the ubiquitous street fighting arcade game. With its blood and spine-ripping moves, Mortal Kombat brought interactive violence of a kind never seen before in living rooms.

Compared to innocuous hits such as the urban-planning game SimCity 2000 or Nintendo’s Super Mario Brothers All-Stars, Mortal Kombat shocked parents and politicians, who believed video games were for kids. The fact that the blood-soaked version of the game for the Sega Genesis was outselling the bloodless version of the game on the family-friendly Nintendo Entertainment System three-to-one only made them more nervous.

The Mortal Kombat panic reached a sensational peak on December 9, 1993, when Democrat senator Joseph Lieberman held the first federal hearings in the United States on the threat of violent video games to children. While culture warriors had fought similar battles over comic books and rock music in the 1950s and over Dungeons & Dragons and heavy metal in the 1980s, the battle over violent games had an urgently contemporary ring. It wasn’t only the content that they were concerned about, it was the increasingly immersive technology that delivered it.

“Because they are active, rather than passive, [video games] can do more than desensitize impressionable children to violence,” warned the president of the National Education Association. When a spokesperson for Sega testified that violent games simply reflected an aging demographic, Howard Lincoln—the executive vice president of Nintendo of America—bristled. “I can’t sit here and allow you to be told that somehow the video game business has been transformed today from children to adults,” he said.

Yet video games had never been only for kids in the first place. They rose up to prominence in the campus computer labs of the 1960s and the 1970s, where shaggy geeks coded their own games on huge mainframe PCs. From there, the Pac-Man fever of home consoles and arcade machines lured millions into the fold. By the early 1990s, legions of hackers were tinkering with their own PCs at home. A burgeoning underground of darkly comic and violent games such as Wolfenstein 3-D and Doom had become a phenomenon among a new generation of college students.

At the same time, Sam’s peers were riding a gritty new wave of art. Films such as Reservoir Dogs and music like Def Jam’s shunned cheesy fantasy for gutsy, pop-savvy realism. These products were bringing a lens to a world that had not previously been portrayed. When Los Angeles erupted in riots after the Rodney King beating, Sam watched—and listened—in awe to the music that reflected the changing times. The fact that Time Warner had dropped “Cop Killer” only seemed to underscore how clueless the previous generation had become.

Now the same battle lines were being drawn over games. To ward off the threat of legislation as a result of the Lieberman hearings, the U.S. video game industry created the Interactive Digital Software Association, a trade group representing their interests. The industry also launched the Entertainment Software Ratings Board to voluntarily assign ratings to their games, most of which fell under E for Everyone, T for Teen, or M for Mature. Less than 1 percent of the titles received an Adults Only or AO rating, the game industry’s equivalent of an X—and, effectively, the kiss of death because major retailers refused to carry AO games.

Yet with Mortal Kombat still burning around the world, the media eagerly fanned the flames. Nintendo, which ruled the industry, had sold a Disneylike image of gaming to the public, but this was now in jeopardy. Video games were “dangerous, violent, insidious, and they can cause everything from stunted growth to piles,” wrote a reporter for the Scotsman, “. . . an incomprehensible fad designed to warp and destroy young minds.”

While the medium was being infantilized by politicians and pundits, however, one of the biggest corporations in the entertainment business was taking up the fight. In 1994, in Japan, Sony was working to release its first-ever home video game console, the PlayStation, built on the idea that gamers were growing up. Phil Harrison, a young Sony executive tasked with recruiting European game developers, thought the game industry was being unfairly portrayed as “a toy industry personified by a lonely twelve-year-old boy in the basement.” Sony’s research told another story—gamers were older and had plenty of money of their own to spend.

The problem with reaching these players started with the hardware. Sony found that although children had no problem pretending their blobs of brown-and-peach pixels were Arnold Schwarzenegger, adults needed more realistic graphics to suspend disbelief and engage. The answer: CD-ROMs. Unlike the cartridges used by Nintendo, a CDROM could hold more content—including full-rendered video—and offer games that were more like what Harrison described as “sophisticated multimedia events.” Combining a high-end graphics machine with an entertainment console was sending a clear message to the industry: it was time for the medium to become more mainstream and grow up.

Sam couldn’t agree more. With the new BMG Interactive division pursuing game publishing, he desperately wanted in. Games were the future, he was sure, and he saw this as a medium through which a guy like him could finally leave his mark. The challenge was to change the meta-game, to bring the experience into a new era, just as the films and the music he loved had redefined their own industries.

Sam urged the BMG brass to give him a break. “I want a go at this,” he told them. “I want to get involved. I’m not involved, but there’s a lot of things I can bring to this situation.” Once again, his doggedness paid off. After graduating from college, he got transferred to the Interactive Publishing division. The game industry worked similar to the record industry. Just as labels put out CDs created by bands, publishers put out software created by developers. They oversaw the production of the game, doling out editorial direction while handling the business, marketing, and packaging. Developers dealt with the front-line creation of the games, from the art to programming.

Hits paid for flops, and if one out of ten games scored, that was enough. BMG’s early games (a backpacking title, a golf simulator), however, fell on the losing side. Yet Sam never gave up hope. Maybe he was crazy. Or maybe, somewhere out there, someone was making a game crazy enough for him.

Chapter 3 Race ’n’ Chase

It would be a grand theft. Stealing the high score in another gang’s territory. Dave Jones couldn’t help himself, though. He could see the Galaga machine flashing inside the fish-and-chips shop like a beacon. The tall black cabinet with the red-eyed, bug-shaped alien warlord on the front. The spiraling electronic theme song. He wanted to touch it. Slip his coin in the vaginal slot, and pound the buttons. Zap the invaders, get the high score, and put his initials at the top.

Yet this was not the part of Dundee, the industrial town north of Edinburgh, Scotland, where he lived. This was Douglas, one of the rougher neighborhoods in a city known for being rough. Once famous for its jute, marmalade, and the invention of Dennis the Menace, Dundee’s economy had tanked by this time in the early 1980s, taking its working-class residents down with it. Teenage gangs with names such as the Huns and the Shams prowled the street, looking for a fight like some Scottish version of The Warriors. Anything could set them off. The wrong look. The wrong football jersey. And especially a gawky, carrot-topped geek in glasses like Jones.

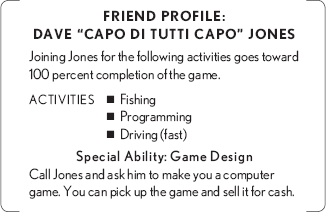

Still in grade school, Jones lived with his parents across town near his dad’s small newspaper shop. When he wasn’t fishing for salmon in the River Tay, he played Space Invaders at the greeting card store near his bus stop. Every day before and after school, he’d make sure to keep the top score.

As he passed through Douglas on an errand, he couldn’t resist having a go at the Galaga machine. His coin dropped inside with a satisfy-ingly metallic plunk. Jones positioned his right pointer finger over the smooth red convex plastic button. He gripped the stick. Hit Start. The onslaught of alien insects on screen began. In a flurry of taps, Jones obliterated the invaders and took the top score—entering his initials for all to see. Who was the real player now?

But the local toughs lurking outside had seen enough. Just as Jones stepped out the door, the gang surrounded him. Who comes here and sets the high score on our turf? Jones ran down the gray cobblestone streets, past the old ladies with their bloated plastic shopping bags, past crusty men smoking unfiltered cigarettes under the overcast sky. The gang tackled him to the ground. As the blows came, he could do nothing but wait for the punches to end. Wait and hope that he would be alive long enough to limp back to the safety of his neighborhood and his own machines.

AS JONES AND HIS OWN GANG of Scottish geeks knew, something electric was coursing over the cobblestone streets of Dundee. A computer revolution had begun. It started at the big brown Timex plant in town, which was churning out the UK’s first popular wave of home computers, the Sinclair ZX81 and the Sinclair ZX Spectrum.

The Spectrum, with its jet-black keyboard and rainbow streak on the side, looked like a control panel to another world. All you needed to know was the code, and you were in. Word had it that Spectrums were “accidentally” falling off delivery trucks—and winding up in the hands of aspiring hackers.

Jones’s high school was among the first in the United Kingdom to offer computer studies, a course that he immediately took. Gifted at math, he taught himself to program and build his own rudimentary machines. On graduation, he scored a job at the Timex plant as an apprentice engineer, but what he really wanted to do was make games. A homebrew computer game scene was percolating from San Francisco to Sweden. Gamers made and distributed their own titles on Apple II and Commodore 64 machines. Jones joined a ragtag gang of computer coders called the Kingsway Amateur Computer Club, who met at the local technical college.

With cuts facing Timex, the company offered Jones £3,000 in voluntary redundancy pay—which he happily blew, in part, on a state-of-theart Amiga 1000 computer (much to the envy of his pals). Though Jones had begun to study software engineering at the local university, his professors and family thought he was nuts. “This is never going to take off,” they told him. “You’re never going to sell enough games to make a living.”

Yet Jones believed in his dreams. With his grades plummeting, he spent late nights in his bedroom at his parents’ house, hatching his plan. While the homebrew scene was dominated by fantasy and sci-fi games, Jones wanted to bring the fast action of arcade hits such as Galaga to home machines. His first game, a kill-the-devil shooter called Menace, was released in 1988 and sold an impressive fifteen thousand copies, earning critical acclaim and £20,000—enough for this car fanatic to buy a 16-valve Vauxhall Astra.

To capitalize on the buzz, he left school and started his own game company, DMA Design, a reference to a computer term, Direct Memory Access. Jones hired friends from the computer club and moved the team into a two-room office on the second floor of a narrow red-and-green building, just above a baby accessories shop called Gooseberry Bush. Pasty-faced with polygonal hair, they looked like extras from a Big Country video. By day, they’d code; by night, hit up the local pubs or compete in games at their office. It was Animal House for nerds. They trashed the office so much that Jones’s wife insisted on coming over to clean the toilet.

This wasn’t just fun and games, though. DMA exemplified the DIY spirit of the times: all you needed was a computer and a dream. Jones was on a mission to make games as cool and fast as his sports car. “We have three to five minutes to capture people,” as he once said. “I don’t care how great your game is, you have three to five minutes.” The edict worked again. Blood Money, billed as “the ultimate arcade game,” came out in 1989 and sold more than thirty thousand copies in two months. Jones felt elated. He was on his way.

In the competitive arena of game making, developers would compete to exploit the latest, greatest programming innovations. One day, a DMA programmer discovered how to animate as many as a hundred characters on screen at a time and made a demo for the team. Jones watched in awe as a line of tiny creatures stupidly marched to their deaths—smashed by a ten-ton weight or incinerated in the mouth of a gun. It was just the sort of dark Scottish humor that got everyone laughing. Let’s make a game out of that!

They called it Lemmings. The object was to save the creatures from dying. Jones’s crew devilishly dreamed up the most punishing fates for the little beasts: falling into holes, getting crushed by boulders, being incinerated in lakes of fire, or getting ripped to shreds by machines. To survive, you had to assign each creature a skill, from digging to climbing, building to bashing. With more than 120 scenes of zig-zagging creatures, the game didn’t only play—it teemed with life.

Lemmings was released on Valentine’s Day 1991 with a warning label: “We Are Not Responsible For: Loss of sanity. Loss of Sleep. Loss of Hair.” Lemmings became an immediate hit, selling fifty thousand copies on its first day alone. The game would go on to earn DMA more than £1.5 million, selling nearly 2 million copies worldwide. “To say that Lemmings took the computer gaming world by storm would be like saying that Henry Ford made a slight impact on the car market,” one reporter wrote.

Just twenty-five, Jones was one of the wealthiest—and most famous—game designers on the planet. His journey from drop-out to millionaire made him one of the industry’s biggest success stories. Ecstatic, he treated himself with his flashiest sports car yet, a Ferrari. Jones hit the road, speeding through the grim city past the gangs. If only there was a game in that.

“FUCK! Fuck! Fuck!”

It was just another day at DMA, and the biggest and most pungent coder on the team was having one of his tantrums again. Game making could be a mind-numbing craft—fashioning living worlds from abstract code—and sometimes this guy had to blow off steam. But as he stood banging his head against a wall and shouting, he saw a sprightly Japanese man beside him. “Oh, my God,” muttered another coder nearby, “that’s Miyamoto!”

Sure enough—it was him, Shigeru Miyamoto, the elfin genius of Nintendo, the inventor of Mario. Not long before, it would have been unthinkable that the biggest name in gaming would grace this little indie start-up in Dundee. Yet with the extraordinary success of Lemmings, Jones had scored a multimillion-pound contract to create two games for the Nintendo 64. “We think David Jones is one of the very few people in the world that are in the Spielberg category,” Howard Lincoln, now the president of Nintendo of America, told the press. Miyamoto, who took the screaming coder in stride, had come to experience the magic of DMA firsthand.

Flush with cash, DMA had moved to a 2,500-square-foot office in a mirrored, militaristic building inside the Dundee Technology Park on the west end of town. Jones invested £250,000 in outfitting their rooms with the best technology they could buy. DMA was said to have one of England’s biggest installations of refrigerator-size Silicon Graphics computers—so big that the minister of defense expressed security concerns. DMA needed the muscle power to bring Jones’s geekiest dream to life: “a living, breathing city.”

Virtual worlds were the stuff of science fiction but still not much of a reality in gaming. The appeal was obvious. Real life could be unpredictable and frustrating, but a synthetic world was something you could control. Jones had, as he put it, “a fascination with how alive and dynamic we could make the city from very little memory and very little processing speed. How could we make something living inside the machine?”

Jones set his team free to come up with their answers. Programmer Mike Dailly engineered a cityscape from a top-down point of view. Another DMAer coded dinosaurs running through the streets. Another replaced the dinosaurs with something cooler, more contemporary, and closer to the boss’s heart: cars. As Dailly watched the little virtual cars speed through the city, he thought, “We have something.”

Jones liked the concept of Cops and Robbers—casting players as the police out to bust the bad guys. “Cops and robbers is a natural rule set that everybody understands,” he said. “They know how to drive a car. They know what a gun does.” Thinking Cops and Robbers too generic a title, they renamed it Race ’n’ Chase instead.

Walking into DMA was like seeing a bunch of grown men playing with a Hot Wheels set—except on their PCs. From the overhead view onscreen, tiny pixilated cars cruised the streets, blips of people climbed onto buses and trains that stopped along their routes. Jones pushed for a more and more realistic simulation. Though cars could speed down the street, they had to stop at traffic lights that blinked from red to green. Jones watched gleefully as his little world teemed with life.