Полная версия

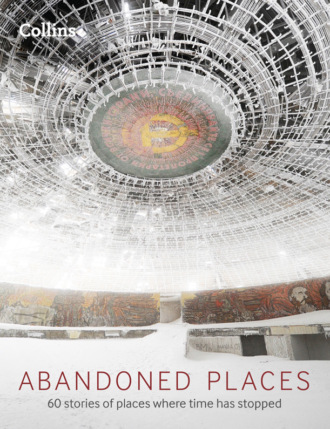

Abandoned Places: 60 stories of places where time stopped

Where did the sculptors go?

‘These stone figures caused us to be filled with wonder, for we could not understand how it was possible that people who are destitute of heavy or thick timber, and also of stout cordage, out of which to construct gear, had been able to erect them.’

So wrote the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen on Easter Sunday, 1722. He had just landed on a rather barren isle with no large trees and a population of around 2,000 people. They had few tools and no mechanical devices. They did not know about the wheel. Their canoes were flimsy and so poorly constructed that they had to be constantly baled out just to stay afloat.

Yet Roggeveen was astonished to see that the island was dotted with hundreds of gigantic stone statues. The islanders had worshipped these moai, by lighting fires at their bases and prostrating themselves to the rising sun.

There were no trees – so how could the inhabitants have made timber for scaffolding and rollers, or thick ropes for hauling the stones? How could a society that was struggling for food spare the time to make and move these gargantuan statues? They obviously couldn’t, and yet the statues were all upright, clear of vegetation and relatively unweathered. This proved that a great civilization had occupied the island in the very recent past. So where had it gone?

Later explorers found a factory-quarry where the moai were cut out of tuff, a compressed volcanic ash. There were dozens of incomplete moai half cut from the rock. Stone tools littered the quarry floor. Several completed moai stood outside the quarry ready for transport to their destination. Had a creative, determined and accomplished people just upped and vanished?

Easter Island is unique among deserted settlements in that it presented its abandonment as a mystery to be solved.

Brave new world

One of the most remarkable things about Easter Island is that it was ever inhabited in the first place. It is one of the most remote populated islands in the world: the nearest inhabited place is Pitcairn Island 2,075 km (1,289 miles) away, while the closest point on the Chilean mainland is 3,512 km (2,182 miles) away.

Moai lined up on their ahu – they face inland.

The only source of fresh water on the island: a volcanic crater.

Humanity first arrived here by canoe from the Marquesas Islands, 3,200 km (2,000 miles) to the west, in AD 1200. At first, life was good for the Rapa Nui, as the inhabitants were known. Pollen analysis has shown that the island was once thickly wooded, and had at least three tree species that grew up to 15 m (49 ft) high. Palms could be felled for the building of large canoes, and the hauhau tree could be used to make ropes. There was an abundance of nesting seabirds and fish. Sturdy canoes enabled the fishermen to take porpoises, which became a vital part of the islanders’ diet.

With ample food for survival the population surged as high as 15,000–20,000. The Rapa Nui had spare time, which they spent making moai. This process was not easy and required great organization: the best stone to carve figures from was found at one site; the preferred rock for the headpieces in a different quarry. The tools were made in yet another location.

Moai abandoned before they reached their ahu (coastal platforms).

Images of the dead

The Rapa Nui sculpted 887 moai. The completed figures were transported over rough, hilly ground to sites all around the island’s coast. There are competing theories about how this was done. The prevailing thinking was that great numbers of trees were felled to create rollers. The moai were then placed on skids or sleds and pulled across the rollers. Other studies maintain that they were walked to their destinations using a rocking technique controlled by teams using ropes.

At their destination they were placed on stone platforms and aligned to face the island’s interior. They were erected to represent the spirits of ancestors, watching over their descendants.

The tallest moai that the islanders erected stood 10 m (33 ft) high and weighed 82 tonnes; but a partially carved sculpture, found abandoned in the quarry, would have stood 21 m (69 ft) high and weighed 270 tonnes.

The island’s population was organized into clans, and moai creation became an artistic battle for tribal bragging rights: the clan that erected the largest and greatest number of moai could claim the highest status.

As moai production spiralled into a virtual frenzy, huge numbers of mature trees must have been brought down. Trees were also being used as fuel for fires and being felled to create fields. The consumption of natural resources began to exceed the rate at which those resources could be regrown. Around the year 1500, the shortage of trees meant many people were living in caves rather than huts. A century later the island was almost completely deforested.

There will have been a point when the islanders realized they were in trouble. The island is only 20 km (12 miles) across and its central peak has a commanding view. It would have been easy to see where the remaining groves of trees were. The man who felled the last tree must have known the irreversible step he was taking.

Now no more moai could be erected. No more canoes could be built, so there would be no more porpoise to eat and no exodus to a promised land.

The loss of the trees also led to the depletion of nutrients in the soil, which reduced crop yield. Food became scarce. Society could no longer afford the luxury of statue-building and so it stopped. With its resources stripped, the island could not support 15,000 people. The Rapa Nui began to die.

A hard lesson to learn

The mysterious abandonment found by the Europeans was therefore more of a slow suicide – and a sobering example of how devastating a man-made ecological disaster can be. In just 400 years a fertile island paradise had been stripped to a husk.

Unfortunately for the Rapa Nui, life was about to get even worse. Slave raids from Peru, diseases brought by visitors and maltreatment all reduced the population further. By 1877 there were only 111 people on the island.

The island’s history since then has been far from straightforward, but today there are 5,800 inhabitants with descendants of the Rapa Nui accounting for around 60 per cent of the population.

Modern-day visitors make the five hour plane trip out into the Pacific to find a strikingly beautiful island with dramatic cliffs, plunging headlands and rolling swards of grass.

They also marvel at the abandoned moai, the physical remains of a ghost culture. The sculptors left testaments to their industry and ingenuity, but precious few explanations for their actions. For the strange irony of the Rapa Nui is that they adapted to live in relative ease so far from other cultures as to be in another world, and yet they couldn’t live with themselves.

Will future civilizations wonder where we went?

ANI

DATE ABANDONED: Eighteenth century

TYPE OF PLACE: Medieval city

LOCATION: Turkey

REASON: Political

INHABITANTS: c. 200,000

CURRENT STATUS: Ruined

A MILLENNIUM AGO THIS WAS THE CAPITAL CITY OF AN EMPIRE THAT STRETCHED FOR HUNDREDS OF KILOMETRES ACROSS EURASIA. IT SURVIVED VIOLENT CENTURIES OF CLASHING KINGS ONLY TO BE FORGOTTEN WHEN THOSE EMPIRES THEMSELVES FADED. NOW IT LIVES ON IN RUINS, FAR FROM THE TOURIST ATTRACTIONS OF TURKEY, A GILDED SHADOW OF ITS FORMER POWER AND GLORY.

The medieval megacity

There were few more magnificent cities anywhere in the world in AD 1000. Perhaps Baghdad could boast the same architectural majesty, and maybe Constantinople had a similar wealth of international trade. But Rome was in ruins, London was a mere Saxon market town and New York was a wooded island. This is Ani: the key military stronghold, the capital city and the cultural heart of a mighty Armenian empire.

Ani lies deep in eastern Turkey, over 1,450 km (900 miles) from Istanbul. Even the nearest town, Kars, is 48 km (30 miles) away. There is precious little in the hinterland but sheep and goats. The plains here roll on and on in every direction, only ended at last by a horizon of slumbering mountains. This feels a long way from civilization; yet a millennium ago it was the centre of one.

The city of 1001 churches

Just before the Norman kings expanded their rule into England, the Bagratuni royal dynasty was crushing local tribal leaders in the area between the Black Sea, Caspian Sea and eastern Mediterranean to create an empire of their own. From AD 961 to AD 1045, Ani was the undisputed capital city of a kingdom that stretched for over 800 km (500 miles) from west to east and 600 km (373 miles) from north to south – a territory that would now include Armenia, eastern Turkey and parts of Azerbaijan, Georgia and northern Iran.

The city was blessed with a superb defensive situation: a steep-sided triangular plateau rising from the ravine of the Akhurian River and the Bostanlar Valley. It also happened to lie at a nexus of trade routes that connected Syria and Byzantium with Persia and Central Asia. The canny Bagratuni capitalized on this location to transform the city into a trade hub close to the Silk Road.

When the seat of Armenian Catholicism relocated to Ani in 992, the city also became the centre of a religious golden age. Churches popped up like desert flowers after a flood, and there were no fewer than twelve bishops within the city leading the faithful in prayer. Ani was famous throughout the region as the ‘City of 1001 Churches’ and the ‘City of Forty Gates’. It was also the sacred resting place of the Bagratuni kings, with an extensive royal mausoleum. The city’s population grew from around 50,000 in the tenth century to well over 100,000 a hundred years later. It probably topped 200,000 at its peak.

Earthquakes have shattered the abandoned churches, mosques and walls of Ani.

Trophy of the empire builders

The city’s strategic location made it a pawn in a vast Eurasian game of chess. It was fought over, sacrificed, taken, even promoted to the status of a queen. The names of the nations fighting changed over the centuries, but Ani saw them all come and go.

From 1044 it came under a wave of Byzantine attacks. In 1064 the town was captured and the inhabitants put to the sword by Seljuk Turks. Over the next 200 years it was owned by Muslim Kurds, Georgians and then Mongols. In the fourteenth century Ani was ruled by another Turkish dynasty, and then the Persians took over, before it became part of the mighty Ottoman Empire in 1579.

By now the city’s day in the sun was dimming into its twilight. The earth’s great empires now lay elsewhere. By the time the site was completely abandoned in 1750, there was only the equivalent of a small town left within the walls.

Lost and found

Ani slumbered in its little nook for a century or so. It was then rediscovered by delighted archaeologists and excavated in 1893. Several thousand of its most important treasures were uncovered and removed before the site could be looted, as happened in the First World War. At the end of that conflict the city was briefly back in Armenian hands before finally being incorporated into Turkey in 1921.

Today the best-preserved monument in the city is the church of St Gregory of Tigran Honents, completed in 1215. On its outer walls, elaborate animal carvings frame panels filled with ancient text. Inside, its frescos still shine with azure, gold and crimson hues as daylight floods the chamber through windows high in the central tower.

Several other churches stand in various states of preservation. A couple look ready to welcome worshippers; some are cloaked in grasses and lichens. The Church of the Redeemer stands like one half of a huge nutshell, its inside exposed to the elements; the church was cleaved in two by a lightning bolt in the 1950s. The rubble from the fallen half has been heaped forlornly in a poor attempt at protecting the half that remains standing.

The Cathedral of Ani has fared better. This architecturally stunning building was completed in AD 1001 and is famed for its pointed arches and clustered piers. These long predate the gothic style of architecture, which would eventually make such features commonplace.

Just down the street from the cathedral is the mosque of Minuchir, the first mosque to be built on the Anatolian plateau. Its 1,000-year-old minaret survives intact along with much of its prayer hall.

Ani was once encircled by powerful defensive walls, and many of these battlements and towers still stand. The walls were doubled in thickness at the northern side where the city was not protected by a river or ravine. Today these sections remain . . . ready to face an enemy that will never come.

There are also the remains of a convent, bathhouses, palaces, streets with shops and ordinary homes, and the abutments of a single-arched bridge over the Arpa River. A few minutes’ walk away in the gorge is an early solution to urban overcrowding – a satellite town of caves cut into the cliffs. The same high architectural standards are evident here: there is even a cave church with frescoes on its walls and ceiling.

The city’s future survival

Earthquakes in 1319, 1832, and 1988, as well as blasting in a nearby quarry and even target practice by the army have all damaged the city’s ancient architecture. Some ham-fisted repair work has done more harm than good. Currently, the city is on the ‘at risk’ register of the World Monuments Fund.

Ani’s sovereignty, meanwhile, remains contested. Today the ruins sit just inside Turkey; Armenia lies a piece of rubble’s throw away across a disputed frontier. Although open to visitors, it remains fenced off in a Turkish military enclave. History would suggest that this may not always remain the case. Ani may have been forgotten by the world at large for several centuries, but the Armenians have always remembered. One day they may yet reclaim their ancient city.

The church of St Gregory of Tigran Honents looks out over the river gorge and the empty plain beyond.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.