Полная версия

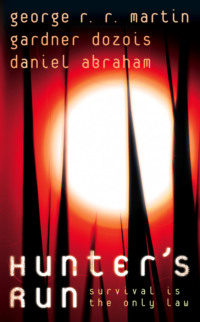

Hunter’s Run

‘You look like shit,’ Elena said, ‘I don’t know why I even let you in my house. Don’t touch that! That’s my breakfast. You can go earn your own!’

Ramon tossed the sausage from hand to hand, grinning, until it cooled enough to take a bite.

‘I work fifty hours a week to make the credit. And what do you do?’ Elena demanded. ‘Loaf around in the terreno cimarrón, come into town to drink whatever you earn. You don’t even have a bed of your own!’

‘Is there coffee?’ Ramon asked. Elena gestured with her chin toward the worn plastic-and-chitin thermos on the kitchen counter. Ramon rinsed a tin cup and filled it with yesterday’s coffee. ‘I’ll make my big find,’ he said. ‘Uranium or tantalum. I’ll make enough money that I won’t have to work again for the rest of my life.’

‘And then you’ll throw me out and get some young puta from the docks to follow you around. I know what men are like.’

Ramon filched another sausage from her plate. She slapped the back of his hand hard enough to sting.

‘There’s a parade today,’ Elena said. ‘After the Blessing of the Fleet. The governor’s making a big show to beam out to the Enye. Make them think we’re all so happy that they came early. There’s going to be dancing and free rum.’

‘The Enye think we’re trained dogs,’ Ramon said around a mouthful of sausage.

Hard lines appeared at the corners of Elena’s mouth, her eyes went cold.

‘I think it would be fun,’ she said, thin venom in her tone. Ramon shrugged. It was her bed he was sleeping in. He’d always known there was a price for its use.

‘I’ll get dressed,’ he said and swilled down the last of the coffee. ‘I’ve got a little money. It can be my treat.’

They skipped the Blessing of the Fleet, Ramon having no interest in hearing priests droning mumbo-jumbo bullshit while pouring dippers of holy water on beaten-up fishing boats, but they’d arrived in time for the parade that followed. The main street that ran past the Palace of the governors was wide enough for five hauling trucks to drive abreast, if they stopped traffic coming the other way. Great floats moved slowly, often stopping for minutes at a time, with secular subjects – a ‘Turu spacecraft’ studded with lights, being pulled by a team of horses; a plastic chupacabra with red-glowing eyes and a jaw that opened and closed to show the great teeth made from old pipes – mixing with oversized displays of Jesus, Bob Marley, and the Virgin of Despegando Station. Here came a twice-life-sized satirical (recognizable but very unflattering) caricature of the governor, huge lips pursed as if ready to kiss the Silver Enyes’ asses, and a ripple of laughter went down the street. The first wave of colonists, the ones who had named the planet São Paulo, had been from Brazil, and although few if any of them had ever been to Portugal, they were universally referred to as ‘the Portuguese’ by the Spanish-speaking colonists, mostly Mexicans, who had arrived with the second and third waves. ‘The Portuguese’ still dominated the upper-level positions in local government and administration, and the highest-paying jobs, and were widely resented and disliked by the Spanish-speaking majority, who felt they’d been made into second-class citizens in their own new home. A chorus of boos and jeers followed the huge float of the governor down the street.

Musicians followed the great lumbering floats: steel bands, string bands, mariachi bands, tuk bands, marching units of zouaves, strolling guitarists playing fado music. Stiltwalkers and tumbling acrobats. Young women in half-finished carnival costumes danced along like birds. With Elena at his side, Ramon was careful not to look at their half-exposed breasts (or to get caught doing so).

The maze of side streets was packed full. Coffee stands and rum sellers; bakers offering frosted pastry redjackets and chupacabras; food carts selling fried fish and tacos, satay and jug-jug; side-show buskers; street artists; fire-eaters; three-card monte dealers – all were making the most of the improvised festival. For the first hour, it was almost enjoyable. After that, the constant noise and press and scent of humanity all around him made Ramon edgy. Elena was her infant-girl self, squealing in delight like a child and dragging him from one place to another, spending his money on candy rope and sugar skulls. He managed to slow her slightly by buying real food – a waxed paper cone of saffron rice, hot peppers, and strips of roasted butterfin flesh, and a tall, thin glass of flavored rum – and by picking a hill in the park nearest the palace where they could sit on the grass and watch the great, slow river of people slide past them.

Elena was sucking the last of the spice from her fingertips and leaning against him, her arm around him like a chain, when Patricio Gallegos caught sight of them and came walking slowly up the rise. His gait had a hitch in it from when he’d broken his hip in a rock-slide; prospecting wasn’t a safe job. Ramon watched him approach.

‘Hey,’ Patricio said. ‘How’s it going, eh?’

Ramon shrugged as best he could with Elena clinging to him like ivy on brick.

‘You?’ Ramon asked.

Patricio wagged a hand – not good, not bad. ‘I’ve been surveying mineral salts on the south coast for one of the corporations. It’s a pain in the ass, but they pay regular. Not like being an independent.’

‘You do what you got to do,’ Ramon said, and Patricio nodded as if he’d said something particularly wise. On the street, the chupacabra float was turning slowly, the great idiot mouth champing at the air. Patricio didn’t leave. Ramon shielded his eyes from the sun and looked up at him.

‘What?’ Ramon said.

‘You hear about the ambassador from Europa?’ Patricio said. ‘He got in a fight last night at the El Rey. Some crazy pendejo stabbed him with a bottle neck or something.’

‘Yeah?’

‘Yeah. He died before they could get him to the hospital. The governor’s real pissed off about it.’

‘So what are you telling me for?’ Ramon asked. ‘I’m not the governor.’

Elena was still as stone beside him, her eyes narrow in an expression of low cunning. Ramon quietly willed Patricio away, or at least to shut up. But the man didn’t pick up on it.

‘The governor’s all busy with the Enye ships coming in. Now he has to track down the guy that killed the ambassador, and show how the colony is able to keep the law and all. I’ve got a cousin who works for the chief constable. It’s ugly over there.’

‘Okay,’ Ramon said.

‘I was just thinking, you know. You hang out at the El Rey sometimes.’

‘Not last night,’ Ramon said, glowering. ‘You can ask Mikel if you want. I wasn’t there all night.’

Patricio smiled and took an awkward step back. The chupacabra made a weak, synthesized roar and the crowd around it shrilled with laughter and applause.

‘Yeah, okay,’ Patricio said. ‘I was just thinking. You know …’

And with the conversation trailing away, Patricio smiled, nodded, and limped back down the hill.

‘It wasn’t you, was it?’ Elena half-whispered, half-hissed. ‘You didn’t kill the fucking ambassador?’

‘I didn’t kill anyone, and sure as hell not a European. I’m not stupid,’ Ramon said. ‘Why don’t you watch your fucking parade, eh?’

Night came on as the parade wound down. At the bottom of the hill, in a field near the palace, they were putting a torch to the pile of wood surrounding Old Man Gloom – Mr Harding, some of the colonists from Barbados called him – a hastily cobbled-together effigy, almost twenty feet tall, with a face like a grotesque caricature of a European or a norteamericano, green-painted cheeks, and an enormous Pinocchio nose. The bonfire blazed, and, wreathed in flames, the giant effigy began to swing its arms and groan in seeming agony, a somehow eerie sight that sent a chill up Ramon’s spine, as if he had been given the dubious privilege of watching a soul being tormented in the fires of Hell.

All the bad luck that dogged people throughout the year was supposed to be burning up with Old Man Gloom, but watching the giant twist and writhe in slow motion in the flames, its deep, electronically amplified moans echoing off the walls of the Palace of the governors, Ramon had a glum presentiment that it was his good luck that was burning instead, that from here on in he was headed for nothing but misery and misfortune.

And one glance at Elena – who had been sitting silently with her jaw set tight and white lines of anger etched around her mouth ever since he had snapped at her – was enough to tell him that it wasn’t going to be very long before that prophecy started to come true.

CHAPTER TWO

He hadn’t intended to go back out for another month. Even though they’d fucked passionately the night before, after one of their most vicious arguments ever, tearing at each other’s bodies like crazed things, he’d decided to leave before she could wake up. If he’d waited, they’d only have had another fight, and she probably would have kicked him out anyway; he’d taken a swing at her with a bottle the night before, and she would be outraged at that once she’d sobered up. Still, if it wasn’t for the killing at the El Rey, he might have tried staying in town. Elena’d probably calm down in a day or two, at least enough that they could speak to each other without shouting, but the news of the European’s death and the governor’s wrath made Diegotown feel close and claustrophobic. When he went to the outfitter’s station to buy rations and water filters, he felt like he was being watched. How many people had been in that crowd? How many of those would know him by sight – or name? The outfitter didn’t have everything on Ramon’s list, but he had bought what was immediately available, and then had flown his van to Manuel Griego’s salvage yard in Nuevo Janeiro. The van needed some work before it could head out into the world, and Ramon wanted it done now.

Griego’s yard squatted at the edge of the city. The hulking frames of old vans and canopy fliers and personal shuttles littered the wide acres. In the hangar, it was equal parts junk shop and clean room. Power cells hung from the rafters, glowing with the eerie light that all Turu technology seemed to carry with it. A nuclear generator the size of a small apartment ran along one wall, humming to itself. Storage units were stacked floor to ceiling; tanks of rare gas and undifferentiated nanoslurry mixed in with half-bald tires and oily drive trains. Half the things in the shop would cost more than a year’s wages just to make use of; half were hardly worth the effort to throw out. Old Griego himself was hammering away on a lift tube as Ramon set his van down on the pad.

‘Hey, ese,’ Griego called out when Ramon popped the doors and came down to the working floor. ‘Long time. Where you been keeping yourself?’

Ramon shrugged.

‘I got a power drop in my back lift tubes,’ he said.

Griego frowned, put down his hammer, and wiped greasy hands on greasy pants.

‘Put on the diagnostic,’ he said. ‘Let’s take a look.’

Of all the men in Diegotown and Nuevo Janeiro – or possibly on this world – Ramon liked old Griego best – which was to say, he only hated him a little. Griego was an expert on all things vehicular, a post-contact Marxist, and, so far as Ramon could make out, totally free of moral judgments. It took them little more than an hour to find where the lift tube’s chipset had lost coherence, replace the card, and start the system’s extensive self-check. As the van stuttered and chuffed to itself, Griego lumbered to one of the gray storage tanks, keyed in a security code, and opened a refrigeration panel to reveal a case of local black beer. He hauled out two bottles, snapping the caps free with a flick of his thick, callused fingers. Ramon took the one that was held out to him, squatted with his back against a drum of spent lubricant, and drank. The beer was thick and yeasty, sediment in the bottom like a spoonful of mud.

‘Pretty good, eh?’ Griego said and drank a quarter of his own at a pull.

‘Not bad,’ Ramon said.

‘So you’re heading out?’

‘This is going to be the big one,’ Ramon said. ‘This time I’m coming back a rich man. You wait. You’ll see.’

‘You better hope not,’ Griego said. ‘Too much money kills men like you and me. God meant us to be poor, or he wouldn’t have made us so mean.’

Ramon grinned. ‘God meant you to be mean, Manuel. He just didn’t want me taking any shit from anybody.’ A quick vision of the European, mouth gaping open, blood gushing out over tombstone teeth, came to him, and he frowned.

Griego was shaking his head. ‘The same thing again, eh? This time’s the one, just like every other time you been out.’ He grinned. ‘You know how many times I heard you say that?’

‘Yep,’ Ramon said. ‘This time’s different, just like always.’

‘Go with God, then,’ Griego said. His grin faded. ‘Everyone’s been scrambling. Trying to get things finished. Aliens caught everyone with their pants around their knees, coming early like this. Funny, though. I don’t see a whole lot of people heading out right now. Pretty much everyone’s coming in for the ships – except you.’

Ramon sneered, but he felt the constant fear in his breast tighten a notch.

‘What? They’re going to give half a shit about a prospector like me? What’s there for me if I stay?’

‘Didn’t say you should,’ Griego said. ‘Just said there’s not many people going out right now.’

I look suspicious, Ramon thought. I look like I’m running from something. He’ll tell the police, and then I’m fucked. He clamped his hand around the bottle so hard his knuckles ached.

‘It’s Elena,’ Ramon said, hoping the half-lie would be convincing enough.

‘Ah,’ Griego said, nodding sagely. ‘I thought it must be something like that.’

‘She kicked me out again,’ Ramon said, trying to sound hang-dog despite the relief washing through him. ‘We had a fight about the parade. It got a little out of hand is all.’

‘She know you’re taking off?’

‘I don’t think she cares,’ Ramon said.

‘Right now, maybe she doesn’t. But you fly out of here and three weeks later she decides that all is forgiven, she’s going to come around tearing up my place.’

Ramon chuckled, remembering the incident that Griego was talking about. He was wrong, though. That hadn’t been about making peace; Elena had convinced herself that Ramon had taken a woman with him when he went out in the field. She hadn’t stopped raging and ranting until she found the girl on whom her paranoia had fixed still in town and involved with one of the magistrates, and even then she still seemed to hold a grudge. Ramon had had to spend almost half the money he’d gotten from his survey work just buying beer and kaafa kyit for all his business contacts whom she’d alienated.

Griego didn’t laugh with him.

‘You know she’s crazy, don’t you?’ he asked instead.

‘She does get pretty wild,’ Ramon said with a half-smile, trying the expression out like it was a new shirt.

‘No, I know wild girls. Elena is fucking loca. I know you like that girl down at the exchange. What’s her name?’

‘Lianna?’ Ramon asked, disbelief in his voice.

‘Yeah that’s the one. Lives over on the north side. Used to be you had a thing with her, didn’t you?’

Ramon remembered those days, when he’d been a younger man, new to the colony. Yes, there had been a woman with coffee-and-milk skin and a laugh that made a man happy just listening to it. Maybe he had even dreamed about her a few times since. But that had carried its own slice of hell with it. Ramon scratched at the scar that striped his belly. Griego raised an eyebrow and Ramon coughed out a laugh.

‘She’s … No. No, she’s not like that. There couldn’t be anything between someone like her and someone like me. And don’t ever let Elena hear you say different.’

Griego gestured his discretion with a wave of his bottle. Ramon took another pull. The thick, earthy taste of the beer was growing on him. He wondered how much alcohol the brew carried.

‘Lianna was a good woman,’ Ramon said. ‘Elena’s like me, though. We understand each other, you know?’ His voice filled with a sudden bitterness that surprised him. ‘We deserve each other.’

‘If you say so,’ Griego said, and the van chimed, its self-test complete. Ramon levered himself up and followed Griego to where the results floated in the air. The power and variance checked at each level, just edging down below optimal on the highest range. Griego waved a crooked finger at the drop.

‘That’s a little weird,’ he said. ‘Maybe we should take another look at –’

‘It’s the cable,’ Ramon said. ‘Salt rats ate through the old one. I had to get gold for the replacement. Couldn’t afford the carbon mesh.’

‘Ah,’ Griego said and clicked his tongue in something between sympathy and disapproval. ‘Yeah, that would do it. Too bad about the rats. That’s the problem with scaring away all the predators, eh? We wind up protecting all the things they used to eat, like salt rats and flatfurs, and then they’re everywhere.’

‘I’ll take a few rats if I don’t have to worry that there’s chupacabras and redjackets in the street every time I go out for a piss,’ Ramon said. ‘Besides, if we didn’t have vermin, how would we know we’d made a real city, right?’

Griego snapped off the display and shrugged. They settled the account; half from Ramon’s available credit, half into an interest bearing tab that the salvage yard’s system kept track of automatically. The sun was setting; the sky pink and gold and blue the color of lapis. Stars glimmered shyly from behind daylight’s veil. And Diegotown spread below them, its lights like a permanent fire. Ramon finished the last of his beer, then spat out the sediment. It left grit between his teeth.

‘The last mouthful’s not the best one,’ Griego said. ‘Still. Beats water.’

‘Amen,’ Ramon said.

‘How long you going out for?’

‘A month,’ Ramon said. ‘Maybe two.’

‘Miss the whole festival.’

‘That’s the idea,’ Ramon agreed.

‘You got enough food for that?’

‘I got hunting gear,’ Ramon said. ‘I could live out there forever if I wanted.’ He was surprised at the wistful, even yearning, tone that he could hear in his own voice.

There was a moment’s silence before Griego spoke again; words that made Ramon’s nerves shrill with sudden fear.

‘You hear about the European that got killed?’

Ramon looked up, startled, but Griego was sucking at his teeth, his expression placid.

‘What about him?’ Ramon asked warily.

‘Governor’s all pissed off about it, from what I hear.’

‘Too bad for the governor, then.’

‘The police came by. Two constables looking real serious. Asked if anyone had been in, getting a van in shape to head out fast. You know, someone who was maybe trying not to be found.’

Ramon nodded, staring at the van. His throat felt tight and the thick beer in his belly seemed to have turned to stone.

‘What did you tell them?’

‘Told them no,’ Griego said with a shrug.

‘There wasn’t anyone?’

‘A couple,’ Griego said. ‘Orlando Wasserman’s kid. And that crazy gringa from Swan’s Neck. But I figured, what the hell, you know? The police don’t pay me, these other people do. So where do my loyalties lie?’

‘Man got killed,’ Ramon said.

‘Yeah,’ Griego agreed, pleasantly. ‘A gringo.’ He spit sideways, then shrugged, as if the death of a gringo or any other kind of European was of no great consequence. ‘I’m just saying it because I’m not the only one they’re asking. You taking off, they may take that the wrong way, give you a hard time about it. Just keep that in mind when you supply up.’

Ramon nodded.

‘They gonna catch him, you think?’ Ramon asked.

‘Oh yeah,’ Griego said. ‘They’ll have to. Bust a gut to do it, if they got to. Show the Enye that we’re a justice-loving people. Not that they care. Shit, fucking Enye lick each other hello. Probably lick the governor and get pissed off if he doesn’t lick them back. Anyway, he’ll make a big show out of the trial, do everything to prove how they got the right guy, then put him down like a fucking dog. You know, whoever it is they decide did it. No one else, there’s always Johnny Joe Cardenas. They’ve been looking for something to hang on him for years.’

‘Maybe it’ll be good that I get out of the city for a while, then,’ Ramon said. He tried a weak smile that felt as obvious as a confession. ‘You know. Just to avoid misunderstandings.’

‘Yeah,’ Griego said. ‘Besides, this is the big one right?’

‘Lucky strike,’ Ramon agreed.

When he started up the van, he could feel the difference. The lift tubes seemed to chime as he lifted up into the sky, all of Diegotown, with its unplanned maze of narrow streets and red-roofed buildings, below him. Elena was down there somewhere. The police too. The body of the European. Mikel Ibrahim and the gravity knife Ramon had handed to him, just handed to him. The murder weapon! And slumped in a bar or a basement opium den – or maybe breaking into someone’s house – Johnny Joe Cardenas, just waiting to hang.

And Lianna, maybe, somewhere in the good section by the port, who didn’t think of Ramon anymore and probably never would.

Ramon’s thoughts were interrupted by the pulsing hum of a shuttle rising up into the thin and distant air. Another load of metal or plastic or fuel or chitin for the welcoming platform. Ramon spun the van north, set it for proximity avoidance, and headed out alone, leaving all the hell and shit and sorrow of Diegotown behind.

CHAPTER THREE

It was a warm day in the Second June. He flew his beat-up old van north across the Fingerlands, the Green-glass country, the river marshes, the Océano Tétrico, heading deep into unknown territory. North of Fiddler’s Jump, the northernmost outpost of the metastasizing human presence on the planet, were thousands of hectares that no one had ever explored, or even thought of exploring, land so far only glimpsed from orbit during the first colony surveys.

The human colony on the planet of São Paulo was only a little more than twenty years old, and the majority of its towns were situated in the subtropic zone of the snaky eastern continent that stretched almost from pole to pole. The colonists were mostly from Brazil and Mexico, with a smattering from Jamaica, Barbados, Puerto Rico, and other Caribbean nations, and their natural inclination was to expand south, into the steamy lands near the equator – they were not effete norteamericanos, after all; they were used to such climates, they knew how to live with the heat, they knew how to farm the jungles, their skins did not sear in the sun. So they looked to the south, and tended to ignore the cold northern territories, perhaps because of an unvocalized common conviction – one anticipated centuries before by the first Spanish settlers in the New World of the Americas – that life was not worth living any place where there was even a remote possibility of snow.

Ramon, however, was part Yaqui, and had grown up in the rugged plateau country of northern Mexico. He liked the hills and white water, and he didn’t mind the cold. He also knew that the Sierra Hueso mountain chain in the northern hemisphere of São Paulo was a more likely place to find rich ore than the flatter country around the Hand or Nuevo Janeiro or Little Dog. The peaks around the Sierra Hueso had been piled up many millions of years before by a collision between continental plates squeezing an ocean out of existence between them; the former seabottom would have been pinched and pushed high into the air along the collision line, and it would be rich in copper and other metals.

Few if any of the muleback prospectors like himself had as yet bothered with the northern lands; pickings were still rich enough down south that the travel time seemed unnecessary to most people. The Sierra Hueso had been mapped from orbit, but no one Ramon knew had ever actually been there, and the territory was still so unexplored that the peaks of the range had not even been individually named. That meant that there were no human settlements within hundreds of miles, and no satellite to relay his network signals this far north; if he got into trouble he would be on his own. He would be one of the first to prospect there, but years would pass, the economic pressure in the south would get higher, and more people would come north, following the charts Ramon had made and sold, interpreting the data he rented out to the corporations and governing bodies. They would follow him like the native scorpion ants – first one, and then a handful, and then countless thousands of small insectoid bodies in the consuming river. Ramon was that first ant, the one driven to risk, to explore. He was a leader not because he chose to be, but because it was his nature to seek distance.