Полная версия

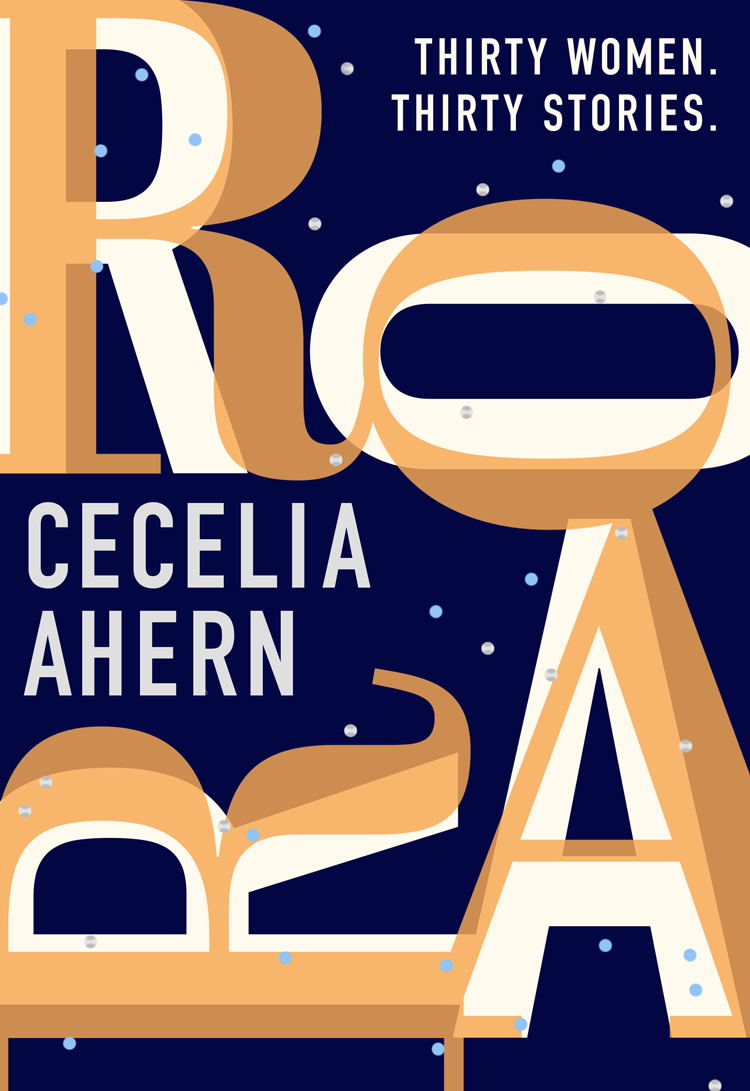

Roar: Uplifting. Intriguing. Thirty short stories from the Sunday Times bestselling author

Copyright

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

Copyright © Cecelia Ahern 2018

Jacket design by Ellie Game © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Cecelia Ahern asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008283490

Ebook Edition © November 2018 ISBN: 9780008283513

Version: 2018-09-04

Dedication

For all the women who …

Epigraph

I am woman, hear me roar, in numbers too big to ignore.

Helen Reddy and Ray Burton

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

1. The Woman Who Slowly Disappeared

2. The Woman Who Was Kept on the Shelf

3. The Woman Who Grew Wings

4. The Woman Who Was Fed by a Duck

5. The Woman Who Found Bite Marks on Her Skin

6. The Woman Who Thought Her Mirror Was Broken

7. The Woman Who Was Swallowed Up by the Floor and Who Met Lots of Other Women Down There Too

8. The Woman Who Ordered the Seabass Special

9. The Woman Who Ate Photographs

10. The Woman Who Forgot Her Name

11. The Woman Who Had a Ticking Clock

12. The Woman Who Sowed Seeds of Doubt

13. The Woman Who Returned and Exchanged Her Husband

14. The Woman Who Lost Her Common Sense

15. The Woman Who Walked in Her Husband’s Shoes

16. The Woman Who Was a Featherbrain

17. The Woman Who Wore Her Heart on Her Sleeve

18. The Woman Who Wore Pink

19. The Woman Who Blew Away

20. The Woman Who Had a Strong Suit

21. The Woman Who Spoke Woman

22. The Woman Who Found the World in Her Oyster

23. The Woman Who Guarded Gonads

24. The Woman Who Was Pigeonholed

25. The Woman Who Jumped on the Bandwagon

26. The Woman Who Smiled

27. The Woman Who Thought the Grass Was Greener on the Other Side

28. The Woman Who Unravelled

29. The Woman Who Cherry-Picked

30. The Woman Who Roared

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Cecelia Ahern

About the Publisher

1

There’s a gentle knock on the door before it opens. Nurse Rada steps inside and closes the door behind her.

‘I’m here,’ the woman says, quietly.

Rada scans the room, following the sound of her voice.

‘I’m here, I’m here, I’m here, I’m here,’ the woman repeats softly, until Rada stops searching.

Her eye level is too high and it’s focused too much to the left, more in line with the bird poo on the window that has eroded over the past three days with the rain.

The woman sighs gently from her seat on the window ledge that overlooks the college campus. She entered this university hospital feeling so hopeful that she could be healed, but instead, after six months, she feels like a lab rat, poked and prodded at by scientists and doctors in increasingly desperate efforts to understand her condition.

She has been diagnosed with a rare complex genetic disorder that causes the chromosomes in her body to fade away. They are not self-destructing or breaking down, they are not even mutating – her organ functions all appear perfectly normal; all tests indicate that everything is fine and healthy. To put it simply, she’s disappearing, but she’s still here.

Her disappearing was gradual at first. Barely noticeable. There was a lot of, ‘Oh, I didn’t see you there,’ a lot of misjudging her edges, bumping against her shoulders, stepping on her toes, but it didn’t ring any alarm bells. Not at first.

She faded in equal measure. It wasn’t a missing hand or a missing toe or suddenly a missing ear, it was a gradual equal fade; she diminished. She became a shimmer, like a heat haze on a highway. She was a faint outline with a wobbly centre. If you strained your eye, you could just about make out she was there, depending on the background and the surroundings. She quickly figured out that the more cluttered and busily decorated the room was, the easier it was for her to be seen. She was practically invisible in front of a plain wall. She sought out patterned wallpaper as her canvas, decorative chair fabrics to sit on; that way, her figure blurred the patterns, gave people cause to squint and take a second look. Even when practically invisible, she was still fighting to be seen.

Scientists and doctors have examined her for months, journalists have interviewed her, photographers have done their best to light and capture her, but none of them were necessarily trying to help her recover. In fact, as caring and sweet as some of them have been, the worse her predicament has grown, the more excited they’ve become. She’s fading away and nobody, not even the world’s best experts, knows why.

‘A letter arrived for you,’ Rada says, stealing her from her thoughts. ‘I think you’ll want to read this one straight away.’

Curiosity piqued, the woman abandons her thoughts. ‘I’m here, I’m here, I’m here, I’m here,’ she says quietly, as she has been instructed to do. Rada follows the sound of her voice, crisp envelope in her extended hand. She holds it out to the air.

‘Thank you,’ the woman says, taking the envelope from her and studying it. Though it’s a sophisticated shade of dusty pink, it reminds her of a child’s birthday party invitation and she feels the same lift of excitement. Rada is eager, which makes the woman curious. Receiving mail is not unusual – she receives dozens of letters every week from all around the world; experts selling themselves, sycophants wanting to befriend her, religious fundamentalists wishing to banish her, sleazy men pleading to indulge every kind of corrupt desire on a woman they can feel but can’t see. Though she’ll admit this envelope does feel different to the rest, with her name written grandly in calligraphy.

‘I recognize the envelope,’ Rada replies, excited, sitting beside her.

She is careful in opening the expensive envelope. It has a luxurious feel, and there’s something deeply promising and comforting about it. She slides the handwritten notecard from the envelope.

‘Professor Elizabeth Montgomery,’ they read in unison.

‘I knew it. This is it!’ Rada says, reaching for the woman’s hand that holds the note, and squeezing.

2

‘I’m here, I’m here, I’m here, I’m here, I’m here,’ the woman repeats, as the medical team assist her with her move to the new facility that will be her home for who knows how long. Rada and the few nurses she has grown close to accompany her from her bedroom to the awaiting limousine that Professor Elizabeth Montgomery has sent for her. Not all the consultants have gathered to say goodbye; the absences are a protest against her leaving after all of their work and dedication to her cause.

‘I’m in,’ she says quietly, and the door closes.

3

There is no physical pain in disappearing. Emotionally, it’s another matter.

The emotional feeling of vanishing began in her early fifties, but she only became aware of the physical dissipation three years ago. The process was slow but steady. She would hear, ‘I didn’t see you there,’ or ‘I didn’t hear you sneak in,’ or a colleague would stop a conversation to fill her in on the beginning of a story that she’d already heard because she’d been there the entire time. She became tired of reminding them she was there from the start, and the frequency of those comments worried her. She started wearing brighter clothes, she highlighted her hair, she spoke more loudly, airing her opinions, she stomped as she walked; anything to stand out from the crowd. She wanted to physically take hold of people’s cheeks and turn them in her direction, to force eye contact. She wanted to yell, Look at me!

On the worst days she would go home feeling completely overwhelmed and desperate. She would look in the mirror just to make sure she was still there, to keep reminding herself of that fact; she even took to carrying a pocket mirror for those moments on the subway when she was sure she had vanished.

She grew up in Boston then moved to New York City. She’d thought that a city of eight million people would be an ideal place to find friendship, love, relationships, start a life. And for a long time she was right, but in recent years she’d learned that the more people there were, the lonelier she felt. Because her loneliness was amplified. She’s on leave now, but before that she worked for a global financial services company with 150,000 employees spread over 156 countries. Her office building on Park Avenue had almost three thousand employees and yet as the years went by she increasingly felt overlooked and unseen.

At thirty-eight she entered premature menopause. It was intense, sweat saturating the bed, often to the point she’d have to change the sheets twice a night. Inside, she felt an explosive anger and frustration. She wanted to be alone during those years. Certain fabrics irritated her skin and flared her hot flushes, which in turn flared her temper. In two years she gained twenty pounds. She purchased new clothes but nothing felt right or fit right. She was uncomfortable in her own skin, felt insecure at male-dominated meetings that she’d previously felt at home in. It seemed to her that every man in the room knew, that everyone could see the sudden whoosh as her neck reddened and her face perspired, as her clothes stuck to her skin in the middle of a presentation or on a business lunch. She didn’t want anybody to look at her during that period. She didn’t want anyone to see her.

When out at night she would see the beautiful young bodies in tiny dresses and ridiculously high-heeled shoes, writhing to songs that she knew and could sing along to because she still lived on this planet even though it was no longer tailored to her, while men her own age paid more attention to the young women on the dance floor than to her.

Even now, she is still a valid person with something to offer the world, yet she doesn’t feel it.

‘Diminishing Woman’ and ‘Disappearing Woman’ the newspaper reports have labelled her; at fifty-eight years old she has made headlines worldwide. Specialists have flown in from around the world to probe her body and mind, only to go away again, unable to come to any conclusions. Despite this, many papers have been written, awards bestowed, plaudits given to the masters of their specialized fields.

It has been six months since her last fade. She is merely a shimmer now, and she is exhausted. She knows that they can’t fix her; she watches each specialist arrive with enthusiasm, examine her with excitement, and then leave weary. Each time she witnesses the loss of their hope, it erodes her own.

4

As she approaches Provincetown, Cape Cod, her new destination, uncertainty and fear make way for hope at the sight before her. Professor Elizabeth Montgomery waits at the door of her practice; once an abandoned lighthouse, it now stands as a grand beacon of hope.

The driver opens the door. The woman steps out.

‘I’m here, I’m here, I’m here, I’m here,’ the woman says, making her way up the path to meet her.

‘What on earth are you saying?’ Professor Montgomery asks, frowning.

‘I was told to say that, at the hospital,’ she says, quietly. ‘So people know where I am.’

‘No, no, no, you don’t speak like that here,’ the professor says, her tone brusque.

The woman feels scolded at first, and upset she has put a foot wrong in her first minute upon arriving, but then she realizes that Professor Montgomery has looked her directly in the eye, has wrapped a welcoming cashmere blanket around her shoulders and is walking her up the steps to the lighthouse while the driver takes the bags. It is the first eye contact she has had with somebody, other than the campus cat, for quite some time.

‘Welcome to the Montgomery Lighthouse Advance for Women,’ Professor Montgomery begins, leading her into the building. ‘It’s a little wordy, and narcissistic, but it has stuck. At the beginning we called it the “Montgomery Retreat for Women” but I soon changed that. To retreat seems negative; the act of moving away from something difficult, dangerous or disagreeable. Flinch, recoil, shrink, disengage. No. Not here. Here we do the opposite. We advance. We move forward, we make progress, we lift up, we grow.’

Yes, yes, yes, this is what she needs. No going back, no looking back.

Dr Montgomery leads her to the check-in area. The lighthouse, while beautiful, feels eerily empty.

‘Tiana, this is our new guest.’

Tiana looks her straight in the eye, and hands her a room key. ‘You’re very welcome.’

‘Thank you,’ the woman whispers. ‘How did she see me?’ she asks.

Dr Montgomery squeezes her shoulder comfortingly. ‘Much to do. Let’s begin, shall we?’

Their first session takes place in a room overlooking Race Point beach. Hearing the crash of the waves, smelling the salty air, the scented candles, the call of the gulls, away from the typical sterile hospital environment that had served as her fortress, the woman allows herself to relax.

Professor Elizabeth Montgomery, sixty-six years old, oozing with brains and qualifications, six children, one divorce, two marriages, and the most glamorous woman she has ever seen in the flesh, sits in a straw chair softened by overflowing cushions, and pours peppermint tea into clashing teacups.

‘My theory,’ Professor Montgomery says, folding her legs close to her body, ‘is that you made yourself disappear.’

‘I did this?’ the woman asks, hearing her voice rise, feeling the flash of her anger as her brief moment is broken.

Professor Montgomery smiles that beautiful smile. ‘I don’t place the blame solely on you. You can share it with society. I blame the adulation and sexualization of young women. I blame the focus on beauty and appearance, the pressure to conform to others’ expectations in a way that men are not required to.’

Her voice is hypnotizing. It is gentle. It is firm. It is without anger. Or judgement. Or bitterness. Or sadness. It just is. Because everything just is.

The woman has goosebumps on her skin. She sits up, her heart pounding. This is something she hasn’t heard before. The first new theory in many months and it stirs her physically and emotionally.

‘As you can imagine, many of my male counterparts don’t agree with me,’ she says wryly, sipping on her tea. ‘It’s a difficult pill to swallow. For them. So I started doing my own thing. You are not the first disappearing woman that I’ve met.’ The woman gapes. ‘I tested and analysed women, just as those experts did with you, but it took me some time to realize how to correctly treat your condition. It took growing older myself to truly understand.

‘I have studied and written about this extensively; as women age, they are written out of the world, no longer visible on television or film, in fashion magazines, and only ever on daytime TV to advertise the breakdown of bodily functions and ailments, or promote potions and lotions to help battle ageing as though it were something that must be fought. Sound familiar?’

The woman nods.

She continues: ‘Older women are represented on television as envious witches who spoil the prospects of the man or younger woman, or as humans who are reactive to others, powerless to direct their own lives; moreover, once they reach fifty-five, their television demographic ceases to exist. It is as if they are not here. Confronted with this, I have discovered women can internalize these “realities”. My teachings have been disparaged as feminist rants but I am not ranting, I am merely observing.’ She sips her peppermint tea and watches the woman who slowly disappeared, slowly come to terms with what she is hearing.

‘You’ve seen women like me before?’ the woman asks, still stunned.

‘Tiana, at the desk, was exactly as you were when she arrived two years ago.’

She allows that to sink in.

‘Who did you see when you entered?’ the Professor asks.

‘Tiana,’ the woman replies.

‘Who else?’

‘You.’

‘Who else?’

‘Nobody.’

‘Look again.’

5

The woman stands and walks to the window. The sea, the sand, a garden. She pauses. She sees a shimmer on a swing on the porch, and nearby a wobbly figure with long black hair looks out to sea. There’s an almost iridescent figure on her knees in the garden, planting flowers. The more she looks, the more women she sees at various stages of diminishment. Like stars appearing in the night sky, the more she trains her eye, the more they appear. Women are everywhere. She had walked right past them all on her arrival.

‘Women need to see women too,’ Professor Montgomery says. ‘If we don’t see each other, if we don’t see ourselves, how can we expect anybody else to?’

The woman is overcome.

‘Society told you that you weren’t important, that you didn’t exist, and you listened. You let the message seep into your pores, eat you from the inside out. You told yourself you weren’t important, and you believed yourself.’

The woman nods in surprise.

‘So what must you do?’ Professor Montgomery wraps her hands around the cup, warming herself, her eyes boring into the woman’s, as though communicating with another, deeper part of her, sending signals, relaying information.

‘I have to trust that I’ll reappear again,’ the woman says, but her voice comes out husky, as if she hasn’t spoken for years. She clears her throat.

‘More than that,’ Professor Montgomery urges.

‘I have to believe in myself.’

‘Society always tells us to believe in ourselves,’ she says, dismissively. ‘Words are easy, phrases are cheap. What specifically must you believe in?’

She thinks, then realizes that this is about more than getting the answers right. What does she want to believe?

‘That I’m important, that I’m needed, relevant, useful, valid …’ She looks down at her cup. ‘Sexy.’ She breathes in and out through her nose, slowly, her confidence building. ‘That I’m worthy. That there is potential, possibility, that I can still take on new challenges. That I can contribute. That I’m interesting. That I’m not finished yet. That people know I’m here.’ Her voice cracks on her final words.

Professor Montgomery places her cup down on the glass table and reaches for the woman’s hands. ‘I know you’re here. I see you.’

In that moment the woman knows for certain that she’ll come back. That there is a way. To begin with, she is focusing on her heart. After that, everything else will follow.

It began shortly after their first date, when she was twenty-six years old, when everything was gleaming, sparkling new. She’d left work early to drive to her new lover, excited to see him, counting down the hours until their next moment together, and she’d found Ronald at home in his living room, hammering away at the wall.

‘What are you doing?’ She’d laughed at the intensity of his expression, the grease, the grime and determination of her newly DIY boyfriend. He was even more attractive to her now.

‘I’m building you a shelf.’ He’d barely paused to look at her before returning to hammering a nail in.

‘A shelf?!’

He continued hammering, then checked the shelf for balance.

‘Is this your way of telling me you want me to move in?’ she laughed, heart thudding. ‘I think you’re supposed to give me a drawer, not a shelf.’

‘Yes, of course I want you to move in. Immediately. And I want you to leave your job and sit on this shelf so that everyone can see you, so that they can admire you, see what I see: the most beautiful woman in the world. You won’t have to lift a finger. You won’t have to do anything. Just sit on this shelf and be loved.’

Her heart had swelled, her eyes filled. By the next day she was sitting on that shelf. Five feet above the floor, in the right-hand alcove of the living room, beside the fireplace. That was where she met Ronald’s family and friends for the first time. They stood around her, drinks in hand, marvelling at the wonder of the new love of Ronald’s life. They sat at the dinner table in the adjoining dining room, and though she couldn’t see everybody she could hear them, she could join in. She felt suspended above them – adored, cherished, respected by his friends, worshipped by his mother, envied by his ex-girlfriends. Ronald would look up at her proudly, that beautiful beam on his face that said it all. Mine. She sparkled with youth and desire, beside his trophy cabinet, which commemorated the football victories from his youth and his more recent golf successes. Above them was a brown trout mounted on the wall on a wooden plate with a brass plaque, the largest trout he’d ever caught, while out with his brother and father. He’d moved the trout to build the shelf, and so it was with even more respect that the men in his life viewed her. When her family and friends came to visit her they could leave feeling assured that she was safe, cocooned, idolized and, more importantly, loved.

She was the most important thing in the world to him. Everything revolved around her and her position in the home, in his life. He pandered to her, he fussed around her. He wanted her on that shelf all of the time. The only moment that came close to the feeling of being so important in his world was Dusting Day. On Dusting Day, he went through all his trophies, polishing and shining them, and of course, he’d lift her from the shelf and lay her down and they would make love. Shiny and polished, renewed with sparkle and vigour, she would climb back up to the shelf again.