Полная версия

Trusted Mole: A Soldier’s Journey into Bosnia’s Heart of Darkness

The Taller One nods, ‘… because of the serious nature of the arrest …’ Oh, you’re so bloody sure of yourself aren’t you!

The PC looks troubled and turns to me. ‘Who would you call?’

I shrug my shoulders. ‘Dunno.’

‘Well, don’t you want to phone a lawyer?’

‘A lawyer? I don’t know any lawyers. What do I need a lawyer for?’

‘Is there anyone you want to call?’

I think – Mum? ‘Hi Mum, I’ve just been arrested by MoD Plod for being a spy … how’s the weather in Cornwall?’ Sister? She’d freak out.

I shake my head, ‘No. No one.’

The PC frowns again and hands me a booklet. ‘You might want to read this in the cell … your rights.’ He stresses the word, glancing at The Taller One. Something clicks – you’ve just made your second mistake, you plonker – two in less than half an hour!

The Taller One and Pot Belly go one way, back out, and I go the other. I’m led down a linoleum-floored passage, the left-hand side punctuated by grey steel doors. The sergeant stops at the last, selects a key from the long chain on his belt, turns it in the lock and heaves open the solid door. I step into the cell.

‘Want anything just press this button – coffee or a light, just buzz for it.’

The door slams heavily shut. The key turns in the lock. Silence. For the first time in my life I find myself on the wrong side of the law and the wrong side of a cell door. I feel weak and sick. My knees tremble. I’m sweating slightly. Delayed shock starts to creep over me.

The cell stinks. Shit, piss, puke, stale smoke, disinfectant. I stare in shock at my bleak surroundings. The cell measures maybe twelve by twelve feet, painted a faded, chipped blue-grey. There are two fixed wooden benches; on top of each of them a blue plastic mattress is propped against the wall. To the left is a small alcove with a toilet – chipped and dirty porcelain, no seat, no chain.

I sit down heavily on the right-hand bench. It’s cold and hard. Dumbly, I stare down at my leather brogues – so out of place – and then fish around in my pockets for a light. I need a cigarette. Shit. No light.

I press the buzzer. Nothing happens. I wait a minute and buzz again. Still nothing. I’m about to try again when a little metal grate, half way up the door, scrapes open. A bored voice says, ‘Yeah. Whaddaya want?’ Whaddaya want!!! … YOU … somehow, my criminalisation is now complete.

‘… Er … do you have a light, please?’ I’m trying to be polite here.

‘… Yeah …’

As if by magic a cheap red lighter appears between fat fingers. For a second there I think it’s Pot Belly’s hand, but he’s busy ransacking my house. A dirty thumb strikes a flame. Gratefully I bend and suck in my first lungful of smoke.

‘Thanks very mu—’ The grate slams shut. Silence again. I exhale noisily and sit back down. My mind is now going bananas. What? Why? Who? When? How?

The tip of the cigarette glows angrily. I’m smoking hard. I light another one from it. What to do with the stub? I hold it in my hand and search for an ashtray. There isn’t one. Above the other bench there’s a barred, thick, frosted glass window. On its ledge there are five or six Styrofoam cups lined up like soldiers. I grab one. It’s brimming with cigarette butts. So’s the next, only these are smeared with garish red lipstick – I wonder who you were?

I sit and chainsmoke five cigarettes. Blue smoke hangs in the cell. The nervous, sinking feeling in my stomach gets worse. My bowels are churning furiously. My head is bursting. Pain straight up my neck, around my brain and down into my teeth. How did this happen?

One minute you’re a student half way through a two-year Staff Course, one of the so-called ‘elite’ top five per cent; doing well, head above water, bright future. And the next, here you are, career blown to smithereens by an arrest warrant for espionage – for spying!? … espionage? … a traitor? How the fuck did this happen? How? How? How?

Despite the pain, ache and worry I’m thinking furiously. How? Connections, seemingly unrelated snippets from the past year and a half.

I’m trying to connect. Random telephone calls. A mysterious major from MoD security. Taped conversations. Jamie’s telling me that people don’t trust me. I voice my concerns. Nothing happens. No one gets back to me.

And then there are the watchers, followers. Horrible, uncomfortable feeling that I’m being watched, followed … for a long time. Eighteen months perhaps. I’ve seen them occasionally – just faces, out of place, people doing nothing, with no reason to be there. Who were they? Croats? Bosnians? Serbs? Someone is watching me. Paranoia? I know I’m being watched. Who’s doing it? Why?

The cell door crashes open, severing my train of thought. I leap to my feet not quite knowing what to expect. It’s the young PC. He’s looking at me, uncertainly, almost sympathetically.

‘We’re not happy about this. I’ve been upstairs to see the Inspector. He agrees with me. We think your civil rights have been abused. You’re entitled to make a phone call. It was obvious to me that you had no one in mind when I asked you who you’d like to call, so, who do you want to call?’

I’m stunned. I can’t believe it. Good on him for doing his job properly.

‘Dunno. Don’t know anyone,’ I stammer.

He’s adamant. ‘Look, it’s only advice, but you do need a lawyer. Really you do.’

‘But I don’t know any lawy—’

He cuts me short. ‘We’ll call you a duty lawyer if you like.’ I nod. He disappears and the door clangs shut. I glance at my watch. Over two hours since I was booked in. Bloody heavy-handed MoD Plod – GUILTY, now let’s prove the case!

Ten minutes later the PC is back. ‘We’ve got you a lawyer. She’s on the phone right now … come on!’ I’m led from the cell and shown to a phone hanging off a wall. The handset’s almost touching the floor. I pick it up and put it to my ear.

‘Hello, I’m Issy White from Tanner and Taylor in Farnborough. I understand you need help …’ Help. What can you do for me?

‘Yes, I suppose I do.’

‘What can you tell me?’ What can I tell you? What should I tell her? How much? All of it? Some of it? Which bits to leave out?

‘Er … well … it’s all very sensitive … I can’t … well, not on the phone …’

‘I’ll be round shortly.’ She’s curt.

I’m pathetically grateful that someone, anyone, has shown interest. Face to face she’s as brusque as she was on the phone. In three hours she has my story, all but the really sensitive stuff. She doesn’t need to know about that at the moment. I tell her about my time out there, about the List, the gong, the phone calls, about everything that matters. She scribbles furiously throughout.

‘Does all this sound unbelievable to you, Issy?’

She looks up and quite matter of factly says, ‘No. It all sounds true. I can spot a liar a mile off.’ She’s very serious.

‘No. I don’t really mean “unbelievable”, I suppose I mean “weird”.’

‘Weird? …’ She pauses, ‘… I’ve never heard anything like it.’

‘Yeah, well, it’s all true, every word of it …’ I feel tired ‘… It’s all true. It happened.’

Issy promises to get me some more cigarettes. She thinks they’ll be finished with my house by two o’clock. She leaves and tells me she’ll be back for ‘question time’.

Back in the cell I’ve got nothing to do except mull over the same old thoughts. Two o’clock comes and goes. Nothing. Three o’clock. Still nothing. I’m dog tired but still thinking, sick and churning but still thinking. What should I tell them? All of it? That would implicate Rose and Smith. Keep it from them. Tell them the minimum. I know what this is about. It’s about phone calls. It’s about a lot more than that. But for now, it’s about phone calls. I’m not about to bubble away Rose, Smith and the others. Not yet anyway. Keep the List out of it.

I’m sitting there staring at my shoes again, my elbows on my knees, head in my hands. I’ve smoked my last cigarette. There’s nothing else to think about. There’s nothing left anymore. Staff College and all that’s happened in the last two and a half years – a dream, a lifetime ago. And now they’re utterly irrelevant to me. Reality is where the illusion is strongest. This is where it’s strongest. Reality is this cell. Nothing else exists and I’m so tired, so, so tired. I have to sleep. Get some strength. Must sleep.

I take off my blazer and lie down on the bench. I can’t be bothered with the mattress. I cover my head with the blazer. It’s all so cold and dark, just like it was then, a thousand years ago – cold, dark, unknown and terrifying. I close my eyes. The tape starts playing and I’m back there. Reality. I can hear the shouts and screams, feel the cold, the panic and the terror. I’m there again.

TWO Operation Grapple – Bosnia

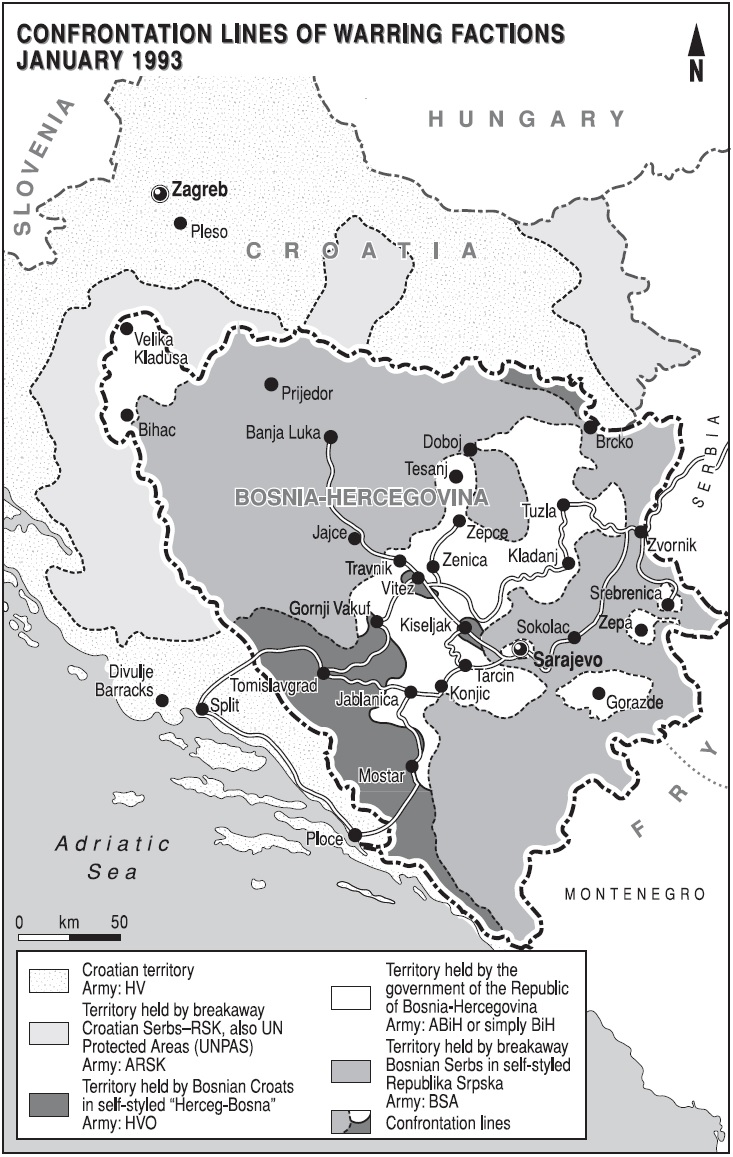

8 January 1993 – British National Support Element Base, Tomislavgrad

The Americans were about to bomb the Iraqis again. On the hour, every hour, the television fixed high in a corner of the dusty warehouse spewed out the impassioned, near hysterical commentaries of the drama unfolding in the Middle East. Iraqi non-compliance with some UN Security Council Resolution seemed to be the issue; cruise missiles were poised to fly, midnight the deadline. In another place at another time we’d all have been glued to the box as we had been in 1991, eagerly anticipating the voyeuristic thrill of technowar. But not this time, not here and not tonight. The crisis in the Persian Gulf seemed so remote, so distant, so unreal. Shattered and numbed by the day’s events, nearly all the soldiers had shuffled off to their makeshift bunk beds, stacked four high around the warehouse.

Being less tired and having nothing more appealing than a sleeping bag on a cold concrete floor to look forward to, I’d delayed getting my head down. I was alone at a small wooden table, determined to finish recording the day’s hectic events in an airmail ‘bluey’ to a stewardess friend at British Airways. I glanced at my bedspace and marvelled that Seb had somehow managed to stuff his massive frame into his doss bag. Even more astonishingly, he’d managed to doze off despite the freezing concrete.

2225. The time flashed on the TV screen as the latest news from the Gulf came in from CNN. I turned back to the letter. Over the page and I’d be done, ‘… so, once the Boss realised what was going on, the three of us spent most of the day driving like madmen to get down here, but it was all over when we arr—.’

Ink splattered across the page. The pen sprang from my fingers as I leapt out of my skin knocking over the table. The newsreader had disappeared from the TV screen, obliterated. My ears were ringing, my mind stunned as a deep WOOOMF slammed into the warehouse, rattled the filthy windows and rolled over and around us. The air was filled with a fluttering, ripping sound and then another shockingly loud detonation somewhere beyond the wall. I was rooted to the spot. My legs started trembling. Adrenalin gushed through my veins.

‘Fuck! Shit! Oh, Christ, not again!’ Expletives echoed around the warehouse.

Pandemonium. All around me soldiers cursing, grunting, wild-eyed, tumbled from their bunks clutching helmets, flak jackets, stuffing feet into boots, laces flying, others scampering off with boots in hand, determinedly dragging their sleeping bags behind them into the darkness of the back of the warehouse.

Seb was on his feet in the same state of stunned confusion as I was. Within seconds the warehouse had emptied. The soldiers seemed to know precisely what to do. Why didn’t we? The greater terror of being left behind seemed to unfreeze me. A corporal raced past. I grabbed at him.

‘Hey! Where do we go? We’ve just arrived.’ Panic in my voice.

He wasn’t going to be stopped. ‘Just follow me, sir!’ he yelled over his shoulder as he disappeared into the gloom. We bolted after him. Ironic that he should be our saviour at that moment; officers were supposed to lead the men. Ridiculous really, but I didn’t care, just so long as he took us to wherever it was everyone else was going.

Cramming ourselves through a small door at the back of the hall, we emerged onto a raised walkway of a loading bay. Turning left we hurried after fleeting, bobbing dark shapes. I hadn’t a clue where we were going and blundered on regardless, driven by panic. We raced through a cavernous, dank boiler room. Another salvo of shells screamed in. Through a door at the far end we were hit by a wall of freezing air. It had been below minus twenty during the day. Now it was even colder.

We were now slipping and stumbling over uneven and frozen gravel. Ahead, stooped and crab-like, dragging doss bags, the black shapes of soldiers darted and weaved – like ghosts caught in the chilling glow of a half moon. Another whirring and ripping of disturbed air. We flung ourselves down grazing palms and knees, cheeks were driven into rough and frozen stones. I clung to the earth as an oily, slithery serpent in my stomach uncurled itself. The night was split for an instant, spiteful red and white followed by a deafening, high-pitched cracking, ringing shockingly loud. Then a deeper note, a rolling wave through the ground beneath, the air swept with an electric, burning hiss.

The desire to remain welded to the earth, panting and cowering, was overwhelming. Although the brain screamed ‘no!’, no sooner had the pulse washed over us than we were up, stumbling across the gravel. With horror I realised we were running towards the impacts. It made no sense. Surely we should be legging it in the opposite direction?

Far in the distance, beyond the broad, flat and featureless plain, now cloaked in darkness, behind a distant, rocky escarpment, two soundless halos of dull yellow flickered briefly. Moments passed and then two flat reports.

‘Incoming!’ screamed a breathless, hysterical voice somewhere ahead.

For seconds, hours, nothing … nothing … then a fluttering warning which sent us diving headlong into the gravel again. More cringing and tensing, detonations, ringing – closer this time. What the fuck are we doing running towards it?

We moved forward, staggering and diving in short bounds for what seemed like an eternity, keeping the edge of the warehouse to our left. In the darkness it was difficult to tell how far we’d gone – time and distance distorted by panic and fear. We rounded the far corner. Beyond a concrete V-shaped ditch was a row of maybe five or six armoured personnel carriers, APCs, neatly parked, squat and black.

I still had the corporal firmly in my sights. In a single bound he vaulted the ditch, raced up to the rear of the left-hand APC, yanked open the rear door and hurled himself inside. Others flung themselves in after him. Another flash on the horizon. Shit!

I was the last into the vehicle and feverishly pulled the door to before the shell landed. It wouldn’t shut. Too many people and too many sleeping bags. It was the bags or me.

‘We don’t need this sodding thing,’ I hissed in desperation, hurling one out into the night. I wrestled the door shut and hauled down on the locking lever just as the shell exploded somewhere to our front.

Inside the APC it was pitch black. Nobody said a word. Nothing could be heard save ragged, terror-edged panting as each man fought to recover his breath. Someone in the front flicked on a torch with a red filter. What little light managed to seep into the back cast eerie patches of dull red across strained, pallid faces. There were far too many of us crammed into the vehicle – knees and elbows everywhere. On my left was a slight youth clad in a boiler suit, who didn’t look like a soldier at all. Opposite me I recognised one of the batch of colloquial interpreters, a staff sergeant in the REME,* evidently posted up to Tomislavgrad, TSG, and now stuck in this APC. He looked terrified. It was his sleeping bag I’d slung out. Two down from me and next to the youth was Seb, still panting furiously. There were others too. Seb’s driver, Marine Dawson, had somehow ended up in the commander’s seat, and somewhere up there was the Sapper corporal, whom we’d blindly followed. There must have been about eight or nine of us stuffed into the small APC.

Our private thoughts were interrupted by a wild banging on the door and muffled shouting. Reluctantly, I eased up the lever and opened the door an inch.

‘Fuck’s sake! Lemme in. Lemme in!’ A helmeted shadow was trying to rip open the door. I held on grimly, not wishing to expose us any more to the outside world.

‘Sorry mate. No room in here … try the one next door …’ I barked through the gap. The shadow swore savagely and disappeared into the night. I slammed the door shut just as another shell screamed in, shattering the night.

‘Oi! You! Get the fucking periscope up!’ It was the corporal, up front somewhere. What was he on about now? Deathly silence. Nothing happened.

‘You in the commander’s seat! Get the periscope up and let’s get a fix on those flashes … work out where the bastards are firing at us from …’ Has be gone mad?

The unfortunate Dawson, who clearly had never been in an APC in his life, frantically started to tug at the various levers and knobs around him. He had no idea what he was supposed to be doing. I’d have been just as clueless. Another shell screamed in.

‘Fuck’s sake, fuck’s sake … get out, get fucking out!’ The corporal had finally lost his rag. A scuffle broke out up front as the shell exploded. In the darkness all you could hear above the high-pitched ringing in your ears were thuds, grunts and the occasional blow as Dawson and the corporal struggled with each other. Somebody whimpered, the APC rocked softly on its suspension, a few more grunts and blows and the unfortunate Marine was ejected from his seat.

Settled in the seat the corporal expertly flipped up the periscope and glued his forehead to the eyepiece. ‘Compass … somebody gimme a compass!’ he yelled without removing his eyes from the optic. His voice rose a note, ‘Shit! ’nother two flashes on the horizon … two rounds incoming!!’

I stared down at the luminous second hand of my watch … five seconds … it swept past ten seconds. Someone started to whimper, another’s breathing rose in volume, great gasping pants … thirteen seconds … my watch started to tremble. I was mesmerised by it … fourteen … fifteen – the air was ripped; two double concussions which rolled into each other. A collective sigh of relief swept through the APC.

‘Where’s that fucking compass?’ The corporal was at it again. Either he was barking mad or had simply been born without fear. He was still determined to get a fix on the guns. I dug out a Silva compass from my smock pocket and passed it up the APC.

‘Time of flight’s about fifteen seconds,’ I shouted up at him.

‘Good. Fifteen seconds, yeah?’ He seemed pleased. What difference did it make? Flashes, bearings, time of flight? The facts couldn’t be altered. We were stuck in this APC. Shells were landing somewhere to our front. A direct hit would destroy the vehicle. A very near miss would destroy it as well, and, with it, us. But I had a sneaking admiration for that unknown corporal. He was one of Kipling’s men, keeping his head and his cool while all around him were losing theirs. At least he was doing something, keeping his mind busy, warding off the intrusion of fear and panic – pure professionalism. I felt useless, unable to contribute in any way, jammed as I was in the rear and prey to my fears and imagination.

What were we doing sitting in an aluminium bucket between the building and the incoming rounds? Surely we’d be safer in the lee of the building, behind it? Another dreadful thought came to mind: the CVR(T) series of vehicles, of which this Spartan was one, were the last of the British Army’s combat vehicles which still ran on petrol. All the others – tanks, armoured infantry fighting vehicles, lorries, Land Rover and plant – ran on diesel. We were sitting on top of hundreds of litres of petrol ‘protected’ only by an aluminium skin. We’d sought refuge inside a petrol bomb. My mind imagined a near miss – red hot steel fragments slicing through aluminium, piercing the fuel tank, which we were sitting on, and wooooossssh ... frying tonight! Fuck this! This was not the place to take cover.

‘Hey! Why don’t we just drive out of here, round the back of the building where it’s safer?’ I shouted at the corporal and anyone else who might care to listen.

‘No driver in the front,’ he shouted back, seemingly unconcerned. I don’t suppose the fuel thing had occurred to him.

‘We had this for four hours this afternoon … just sat here, froze and waited … shit myself,’ mumbled the staff sergeant opposite and then he added savagely, ‘I’ve fucking had enough of this shite!’

‘Another flash!’ screamed the corporal. Bugger him! Why did he have to be so efficient? I didn’t want to know that another shell was arcing towards us. This is the one that’s going to fry us!… three seconds … the panting started … five seconds … where were Corporal Fox and Brigadier Cumming? Where had they taken cover? … seven seconds ... How had we got ourselves into this? How eager and consumed with childish enthusiasm we’d been, desperate not to miss out! How we’d raced down to TSG – and for what? … nine seconds. ... Idiots! The lot of us.

We’d been in Vitez that morning. In fact we’d just left the Cheshire Regiment’s camp at Stara Bila when it happened. We’d driven there from Brigadier Cumming’s tactical headquarters in the hotel in Fojnica. He’d been incensed by an article in the Daily Mail, written by Anna Pukas, which had glorified the British contribution to the UN and had damned, by omission, everyone else’s. We’d dropped by the Public Information house in Vitez late the previous night after a gruelling eleven-hour trip up into the Tesanj salient. Cumming had returned to the Land Rover Discovery clutching a fax of the article. He’d been livid but it had been too late to do anything about it at that hour so we’d returned to Fojnica. The following day we shot back to Vitez where Cumming had words with the Cheshires’ Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Bob Stewart, who had been quoted in the article.

We were heading back to Fojnica and had been on the road some ten minutes. The Brigadier was silent. Corporal Fox was concentrating on keeping the vehicle on the icy road and the accompanying UKLO team – an RAF flight lieutenant called Seb, his driver, Marine Dawson, and their wretched satellite dish in the back of their RB44 truck – in his rear-view mirror. Next to his pistol on the dash the handset of our HF radio spluttered and hissed into life. It was always making strange noises and ‘dropping’ so I never paid much attention to it. Corporal Fox grabbed it and stuck it to his ear.

‘Sir, I’m not sure, but it sounds like something’s going on in TSG … signal’s breaking up and I can’t work out their call sign … sounds like they’re being shelled or are under attack.’ Corporal Simon Fox was a pretty cool character, never flustered, always the laconic Lancastrian. I couldn’t make much sense with the radio either. Static and atmospherics were bad. All we could hear was a booming noise in the background. We decided to head back to Vitez.

The Operations Room at Vitez was packed. We entered to a deathly, expectant hush as everyone strained to hear the transmissions from TSG.

‘… that’s forty-seven and they’re still landing … forty-nine, fifty … still incoming …’ There was no mistaking it: TSG was definitely being shelled and some brave soul was still manning a radio, probably cowering under a desk, and was giving a live commentary as each shell landed.