полная версия

полная версияRambles and Recollections of an Indian Official

593

The area is much larger than 40 acres, being really about 150 acres. Each side is approximately 3½ furlongs.

594

This remarkable eulogium is quoted with approval by another enthusiastic admirer of Akbar, Count von Noer (Prince Frederick Augustus of Schleswig-Holstein), who observes that 'as Akbar was unique amongst his contemporaries, so was his place of burial among Indian tombs—indeed, one may say with confidence, among the sepulchres of Asia.' (The Emperor Akbar, a Contribution towards the History of India in the 16th Century, by Frederick Augustus, Count of Noer; edited from the Author's papers by Dr. Gustav von Buchwald; translated from the German by Annette S. Beveridge. Calcutta, 1890.) This work of Count von Noer, unsatisfactory though it is in many respects, is still the best exiting modern account of Akbar's reign. The competent scholar who will undertake the exhaustive treatment of the life and reign of Akbar will be in possession of perhaps the finest great historical subject as yet unappropriated. The editor long cherished the idea of writing such an exhaustive work, but if he should now attempt to deal with the fascinating theme, he must be content with a less ambitions performance. Colonel Malleson's little book in the 'Rulers of India' series, although serviceable as a sketch, adds nothing to the world's knowledge. Akbar's reign (1556-1605) was almost exactly coincident with that of Queen Elizabeth (1558-1603). The character and deeds of the Indian monarch will bear criticism as well as those of his great English contemporary. 'In dealing', observes Mr. Lane-Poole, 'with the difficulties arising in the Government of a peculiarly heterogeneous empire, he stands absently supreme among Oriental sovereigns, and may even challenge comparison with the greatest of European rulers.'

Unhappily, there is reason to believe that the marble slab no longer covers the bones of Akbar. Manucci states positively that 'During the time that Aurangzēb was actively at war with Shivā Jī [scil. the Marāthās], the villagers of whom I spoke before broke into the mausoleum in the year 1691 [in words], and after stealing all the stones and all the gold work to be found, extracted the king's bones and had the temerity to throw them on a fire and burn them' (Storia do Mogor, i. 142). The statement is repeated with some additional particulars in a later passage, which concludes with the words: 'Dragging out the bones of Akbar, they threw them angrily into the fire and burnt them' (ibid. ii. 320). Irvine notes that the plundering of the tomb by the Jāts is mentioned in detail by only one other writer, Ishar Dās Nāgar, author of the Fatūhāt-I- Alamgīrī, a manuscript in the British Museum. Manucci seems to be the sole authority for the alleged burning of Akbar's bones. I should be glad to disbelieve him, but cannot find any reason for doing so.

595

The names and titles of the empress 'over whose remains the Tāj is built' were Nawāb Aliyā Begam, Arjumand Bānū, Mumtāz-i-Mahall. The title Nūr Mahall, as applied to her, is without authority: it properly belongs to her aunt. 'It is usual in this country', Bernier observes, 'to give similar names to the members of the reigning family. Thus the wife of Chah-Jehan—so renowned for her beauty, and whose splendid mausoleum is more worthy of a place among the wonders of the world than the unshapen masses and heaps of stones in Egypt—was named Tāge Mehalle [Mumtāz-i-Mahall], or the Crown of the Seraglio; and the wife of Jehan-Guyre, who so long wielded the sceptre, while her husband abandoned himself to drunkenness and dissipation, was known first by the name of Nour Mehalle, the Light of the Seraglio, and afterwards by that of Nour-Jehan-Begum, the Light of the World.' (Bernier, Travels, ed. Constable, and V. A. Smith, 1914, p. 5.)

596

Properly, Ghiās-ud-dīn, meaning 'succourer of religion'. The word Ghiās cannot stand as a name by itself.

597

The author's slight description of Itimād-ud-daula's exquisite sepulchre is, in the original edition, illustrated by two coloured plates, one of the exterior, and the other of the interior (restored). The lack of grandeur in this building is amply atoned for by its elegance and marvellous beauty of detail. An inscription, dated A.H. 1027 = A.D. 1618, alleged to exist in connexion with the building, has not, apparently, been published. (N.W.P. Gazetteer, 1st ed., vol. vii, p. 687.)

Fergusson's description and just criticism deserve quotation. 'The tomb known as that of Itimād-ud-daula, at Agra, . . . cannot be passed over, not only from its own beauty of design, but also because it marks an epoch in the style to which it belongs. It was erected by Nūr-Jahān in memory of her father, who died in 1621, and [it] was completed in 1628. It is situated on the left bank of the river, in the midst of a garden surrounded by a wall measuring 540 feet on each side. In the centre of this, on a raised platform, stands the tomb itself, a square measuring 69 feet on each side. It is two stories in height, and at each angle is an octagonal tower, surmounted by an open pavilion. The towers, however, are rather squat in proportion, and the general design of the building very far from being so pleasing as that of many less pretentious tombs in the neighbourhood. Had it, indeed, been built in red sandstone, or even with an inlay of white marble like that of Humāyūn, it would not have attracted much attention, its real merit consists in being wholly in white marble, and being covered throughout with a mosaic in 'pietra dura'—the first, apparently, and certainly one of the most splendid, examples of that class of ornamentation in India....

'As one of the first, the tomb of Itimād-ud-daula was certainly one of the least successful specimens of its class. The patterns do not quite fit the places where they are put, and the spaces are not always those best suited for this style of decoration. [Altogether I cannot help fancying that the Italians had more to do with the design of this building than was at all desirable, and they are to blame for its want of grace.[a]] But, on the other hand, the beautiful tracery of the pierced marble slabs of its Windows, which resemble those of Salīm Chishtī's tomb at Fatehpur Sikrī, the beauty of its white marble walls, and the rich colour of its decorations, make up so beautiful a whole, that it is only on comparing it with the works of Shāh Jahān that we are justified in finding fault.' (Indian and Eastern Architecture, ed. 1910, pp. 305-7.) Further details will be found in Syad Muhammad Latīf, Agra (Calcutta, 1896); A.S.R. iv, pp. 137-41 (Calcutta, 1874); and more satisfactorily, in E. W. Smith, Moghul Colour Decoration of Agra (Allahabad, 1901), pp. 18-20, pl. lxv-lxxvii. Mr. E. W. Smith, if he had lived, would have produced a separate volume descriptive of this unique building.

The building is now carefully guarded and kept in repair. The restoration of the inlay of precious stones is so enormously expensive that much progress in that branch of the work is impracticable. The mausoleum contains seven tombs.

a. This sentence has been deleted by Dr. Burgess in his edition, 1910.

598

This tale is mythical. The alleged circumstances could not be known to any person besides the father and mother, neither of whom would be likely to make them public. Blochmann (transl. Āīn, i. 508) gives a full account of Itimād-ud-daula and his family. The historians state that Nūr Jahān was born at Kandahār, on the way to India. Her father was the son of a high Persian official, but for some reason or other was obliged to quit Persia with his family. He was a native of Teheran, not of 'Western Tartary'. The personal name of Nūr Jahān was Mihr-un-nisā.

599

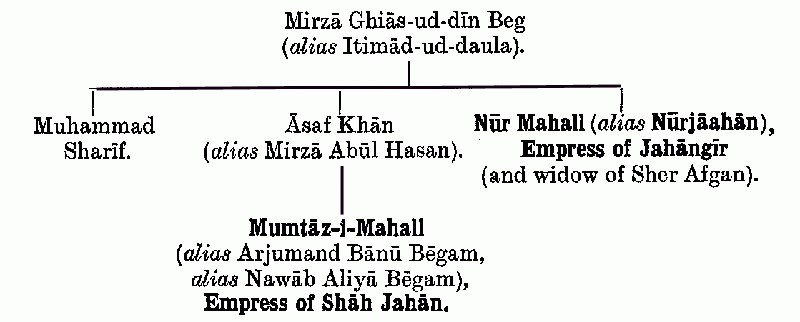

This story is erroneous, and inconsistent with the correct statement in the heading of the chapter that Nūr Jahān, daughter of Ghiās-ud-dīn, was aunt of the Lady of the Tāj. The author makes out Ghiās-ud-dīn (whom he corruptly calls Aeeas) to be a distant relation of Āsaf Khan. In reality, Āsaf Khān (whose original name was Mirzā Abūl Hasan) was the second son of Ghiās-ud- dīn, and was elder brother of Nūr Jahān, The genealogy, so far as relevant, is best shown in a tabular form, thus:—

600

Alī Qulī Beg, from Persia entered Akbar's service, and in the war with the Rānā of Chitōr, served under Prince Salīm (Jahāngīr), who gave him the title of Shēr Afgan, 'tiger-thrower', with reverence to his deeds of prowess. The spelling afgan is correct. The word is the radical of the Persian verb afgandan, 'to throw down'.

601

In October, 1605.

602

Properly Kutb-ud-dīn Khan. He was foster-brother of Prince Salīm (Jahāngīr), and his appointment as viceroy alarmed Shēr Afgan, and caused the latter to throw up his appointment in Bengal. The word Kutb (Qutb) cannot stand alone as a name. Kutb (Qutb)-ud-dīn means 'pole-star of religion'.

603

Tāndān, or Tānra. Ancient town, now a petty village, in Mālda District, Bengal, the capital of Bengal after the decadence of Gaur. Its history is obscure, and the very site of the city has not been accurately determined. It is certain that it was in the immediate neighbourhood of Gaur, and south- west of that town beyond the Bhāgīrathī. Old Tāndān has been utterly swept away by the changes in the course of the Pāglā. It was occupied by the Afghan king of Bengal in A.D. 1564, and is not mentioned after 1660. (I.G., 1908.)

604

This narrative, notwithstanding all the minute details with which it is garnished, cannot be accepted as sober history; and I do not know from what source the author obtained it. 'This lady, whose maiden name was Muhr-un-Nisā, or "Seal of Womankind", had attracted the admiration of Jahāngīr when he was crown prince, but Akbar married her to a young Turkomān and settled them in Bengal. After Jahāngīr's accession the husband was killed in a quarrel with the governor of the province, and the wife was placed under the care of one of Akbar's widows, with whom she remained four years, and then married Jahāngīr (1610). There is nothing to justify a suspicion of the Emperor's connivance in the husband's death; nor do Indian historians corroborate the invidious criticisms of "Normal" by European travellers; on the contrary, they portray Nūr-Mahall as a pattern of all the virtues, and worthy to wield the supreme influence which she obtained over the Emperor.' (Lane-Poole, The History of the Moghul Emperors of Hindustan illustrated by their Coins, p. xix.) The authorities on which this statement is founded are given in E. & D., vol. vi, pp. 397 and 402-5. See also Blochmann, Āīn, vol. i, pp. 496, 524. Details of such stories in the various chronicles always differ. Jahāngīr openly rejoiced in the death of Shēr Afgan, and it is by no means clear that he was not responsible for the event. He was not troubled by nice scruples. The first element in the lady's personal name seems to be Mihr, 'sun', not Muhr, 'seal'. The words are identical in ordinary Persian writing.

605

The long interval which elapsed between Shēr Afgan's death and the marriage with the Emperor is a fact opposed to the assumptions which the author adopts that Nūr Mahall was 'nothing loth', and that the death of her first husband was contrived by Jahāngīr.

606

Quaint Sir Thomas Herbert thus expresses himself: 'Meher Metzia [Mihr-un-nisā] is forthwith espoused with all solemnity to the King, and her name changed to Nourshabegem [Nūr Shāh Bēgam], or Nor-mahal, i.e., Light or Glory of the Court; her Father upon this affinity advanced upon all the other Umbraes ['umarā', or nobles]; her brother, Assaph-Chan [Āsaf Khān], and most of her kindred, smiled upon, with the addition of Honours, Wealth, and Command. And in this Sun-shine of content Jangheer [Jahāngīr] spends some years with his lovely Queen, without regarding ought save Cupid's Currantoes' (Travels, ed. 1677, p. 74). Authority exists for the title Āsaf Jāh, as well as for the variant Āsaf Khān.

Coins were struck in the joint names of Jahāngīr and his consort, bearing a rhyming Persian couplet to the effect that

'By command of Jahāngīr the King, from the name of Nūr Jahān his Queen, gold gained a hundred beauties.'

The Queen's administration is censured by some of the European travellers who visited India during Jahāngīr's reign as being venal and inefficient, and she is accused of cruelty and perfidy. She died on the 18th December (N.S.), 1645, and was buried by the aide of Jahāngīr in his mausoleum at Lahore. At her death she was in her 72nd year, according to the Muhammadan lunar reckoning, and would thus have been thirty-four solar years of age when the Emperor married her in 1610 (Beale: Blochmann).

607

According to Sir Thomas Herbert (Travels, ed. 1677, p. 99), 'Queen Normahal and her three daughters' were confined by order of Shāh Jahān in A.D. 1628.

608

Son of Bhagwān Dās, of Ambēr or Jaipur, in Rājputāna, and one of the greatest of Akbar's officers.

609

Also known as Azīz Kokah, a foster-brother of Akbar.

610

This story may or may not be true; but a charge of this kind is absolutely incapable of proof, and would be readily generated in the palace atmosphere.

611

According to a contemporary authority, the blinding was only partial, and the prince recovered the sight of one eye (E. & D. vi. 448). With regard to such details the discrepancies in the histories are innumerable.

612

A.H. 1031 = A.D. 1621-2. The charge seems to be true.

613

A.H. 1036 = A.D. 1626-7.

614

This is a blunder. Jahāngīr's fourth son was named Jahāndār, and died in or about A.H. 1035 = A.D. 1625-6. Dāniyāl was third son of Akbar, and younger brother of Jahāngīr. He died from delirium tremens in A.D. 1605, a few months before the death of Akbar,

615

Jahāngīr died, when returning from Kāshmīr, on the 8th November, A.D. 1627 (N.S.), and was buried near Lahore. The fight with Shahryār took place at Lahore.

616

Bulākī assumed the title of Dāwar Baksh during his short reign, and struck coins at Lahore. He 'vanished—probably to Persia—after his three months' pretence of royalty; and on 25th January, 1628 (18 Jumāda I, 1037), Shāh-Jahān ascended at Agra the throne which he was to occupy for thirty years'. Shahryār was known by the nickname of Nā-shudanī, or 'Good-for-nothing' (Lane- Poole, The History of the Moghul Emperors of Hindustan, illustrated by their Coins, p. xxiii). The two nephews of Jahāngīr, the sons of Dāniyāl, slaughtered at this time, had been, according to Herbert, baptized as Christians (Travels, ed. 1677, pp. 74, 98). There are great discrepancies in the accounts given by various authorities concerning the fate of Bulākī and the other victims of Shāh Jahān. A dissuasion of the evidence would take too much apace, and must be inconclusive, the fact being that the proceedings were secret, and pains were taken to conceal the truth.

617

The dates of birth are, in Old Style:-Dārā Shikoh, March 20, 1615; Sultan Shujā, May 12, 1616; Aurangzēb, October 10, 1619; and Murād Baksh, not stated (Beale).

618

Ante, Chapter 2, text following [8]. The quotation is from Part III, chap. 19, p. 35 of The Travels of Monsieur de Thevenot, now made English. London, Printed in the year MDCLXXXVII. The author, in his quotation, omits between 'that' and 'The Dutch' the clause 'This indeed is certain that there are few Heathens and Parsis in respect of Mahometans there, and these surpass all the other sects in power as they do in number.'

619

During the reign of Akbar, many Christians, Portuguese, English, and others, visited Agra, and a considerable number settled there. A Roman Catholic church was built, the steeple of which was pulled down by Shāh Jahān. The oldest inscriptions in the cemetery adjoining the Roman Catholic cathedral are in the Armenian character. Three Catholic cemeteries exist at or near Agra, namely

(1) the old Catholic graveyard at the village of Lashkarpur, dating from the time of Akbar, who made a grant of the site about A.D. 1600. This cemetery includes the Martyrs' Chapel, also known as the Chapel of Father Santus (Santucci), which was erected in memory of Khoja Mortenepus, an Armenian merchant, whose epitaph is dated 1611. The next oldest tombstone, that of Father Emmanuel d' Anhaya, who died in prison, bears the date August, 1633. Father Joseph de Castro, who died at Lahore, on December 15, 1646, lies in the same building.

(2) A cemetery in Pādrītola, the native Christian ward of the city behind the old cathedral. Father Tieffenthaler is buried there.

(3) A cemetery in an unnamed village, granted by Jahāngīr, and situated a mile north of Lashkarpur. An unpublished letter in the British Museum shows that Jahāngīr closed the churches in his dominions in 1615. Notwithstanding, the College at Agra was founded about 1617 by an Armenian who is known by his title Mirzā Zul-Qarnain. The acute persecution by Shāh Jahān occurred in 1631.

The artillery men in the Mogul service were not all European Christians. Turks from the Ottoman Empire were freely employed. (See Ep. Ind., ii, 132 note.)

The facts concerning the early history of Christianity in Northern India have been imperfectly studied. In this note I have used chiefly a pamphlet by Father H. Hosten, S. J., entitled Jesuit Missionaries in Northern India, &c. (Catholic Orphan Press, Calcutta, 1907), and the confused little book by Fanthome, Reminiscences of Agra (2nd ed., Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta, 1895). The Jesuit and Capuchin Fathers are working at the subject and hope to elucidate it. From the A.S. Progress Rep. N. Circle, Muhammadan Monuments, for 1911-12, p. 21, it appears that arrangements for the proper maintenance of the Old Catholic cemetery are in hand.

The author's observations concerning the official relations of Christianity in India do not apply at all to the very ancient churches of the South (See E.H.I., 3rd ed., 1914, App. M, pp. 245-7). Even in the north, the modern missionary operations may claim to be 'independent of office'.

620

Govardhan is a very sacred place of pilgrimage, full of temples, situated in the Mathurā (Muttra) district, sixteen miles west of Mathurā, Regulation V of 1826 annexed Govardhan to the Agra district. In 1832 Mathurā was made the head- quarters of a new district, Govardhan and other territory being transferred from Agra.

621

The Purānas, even when narrating history after a fashion, are cast in the form of prophecies. The Bhāgavat Purāna is especially devoted to the legends of Krishna. The Hindī version of the 10th Book (skandha) is known as the 'Prēm Sāgar', or 'Ocean of Love', and is, perhaps, the most wearisome book in the world.

622

This flight occurred during the struggles following the battle of Plassy in 1757, which were terminated by the battle of Buxar in 1764, and the grant to the East India Company of the civil administration of Bengal, Bihār and Orissa in the following year. Shāh Ālam bore, in weakness and misery, the burden of the imperial title from 1759 to 1806. From 1765 to 1771 he was the dependent of the English at Allahabad. From 1771 to 1803 he was usually under the control of Marāthā chiefs, and from the time of Lord Lake's entry into Delhi, in 1803 he became simply a prisoner of the British Government. His successors occupied the same position. In 1788 he was barbarously blinded by the Rohilla chief, Ghulām Kādir.

623

Akbar II. His position as Emperor was purely titular.

624

The name is printed as Booalee Shina in the original edition. His full designation is Abū Alī al-Husain ibn Abdullah ibn Sīnā, which means 'that Sīnā was his grandfather. Avicenna is a corruption of either Abū Sīnā or Ibn Sīnā. He lived a strenuous, passionate life, but found time to compose about a hundred treatises on medicine and almost every subject known to Arabian science. He died in A.D. 1037. A good biography of him will be found in Encyclo. Brit., 11th ed., 1910.

625

Otherwise called Eurasians, or, according to the latest official decree, Anglo-Indians.

626

'Diplomatic characters' would now be described as officers of the Political Department.

627

These remarks of the author should help to dispel the common delusion that the English officials of the olden time spoke the Indian languages better than their more highly trained successors.

628

The author wrote these words at the moment of the inauguration by Lord William Bentinck and Macaulay of the new policy which established English as the official language of India, and the vehicle for the higher instruction of its people, as enunciated in the resolution dated 7th March, 1835, and described by Boulger in Lord William Bentinck (Rulers of India, 1897), chap. 8. The decision then formed and acted on alone rendered possible the employment of natives of India in the higher branches of the administration. Such employment has gradually year by year increased, and certainly will further increase, at least up to the extreme limit of safety. Indians now (1914) occupy seats in the Council of India in London, and in the Executive and Legislative Councils of the Governor- General, Provincial Governors, and Lieutenant-Governors. They hold most of the judicial appointments and fill many responsible executive offices.

629

Khojah Nasīr-ud-dīn of Tūs in Persia was a great astronomer, philosopher, and mathematician in the thirteenth century. The author's Imām-ud-dīn Ghazzālī is intended for Abū Hāmid Imām al Ghazzālī, one of the most famous of Musulmān doctors. He was born at Tūs, the modern Mashhad (Meshed) in Khurāsān, and died in A.D. 1111. His works are numerous. One is entitled The Ruin of Philosophies, and another, the most celebrated, is The Resuscitation of Religious Sciences (F. J. Arbuthnot, A Manual of Arabian History and Literature, London, 1890). These authors are again referred to in a subsequent chapter. I am not able to judge the propriety of Sleeman's enthusiastic praise.

630

The gentleman referred to was Mr. John Wilton, who was appointed to the service in 1775.

631

The cantonments at Dinapore (properly Dānāpur) are ten miles distant from the great city of Patna.

632

The rupee was worth more than two shillings in 1810. The remuneration of high officials by commission has been long abolished.

633

There used to be two opium agents, one at Patna, and the other at Ghāzīpur, who administered the Opium Department under the control of the Board of Revenue in Calcutta. In deference to the demands of the Chinese Government and of public opinion in England, the Agency at Ghāzīpur has been closed, and the Government of India is withdrawing gradually from the opium trade. Such lucrative sinecures as those described in the text have long ceased to exist.

634

These Persian words would not now be used in orders to servants.