полная версия

полная версияRollo on the Rhine

"Yes," said Rollo. "The silver vessels were on a little shelf at first, at the side of the altar, and he went at the proper time and kneeled with them by the side of the priest, until the priest was ready to take them."

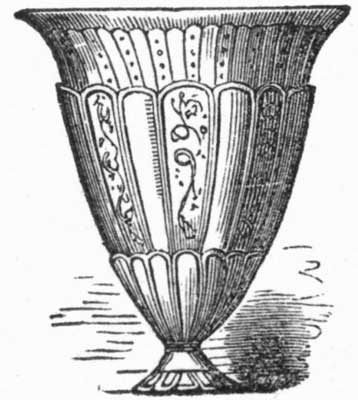

"One of these vessels," continued Mr. George, "contained wine, the other water. When the priest held his large silver cup out to him, the man poured some of the wine into it."

"Yes," said Rollo. "And I saw the priest wiping out the cup very carefully, with a large white napkin, before he held it out for the wine."

"True," said Mr. George. "When he took the wine in his cup, it was common wine, in its natural state; but afterwards, by being consecrated to the service of the mass, it was changed, they all believe, into the blood of Christ. It looked, they knew, just as it did before; but though it thus still retained all the appearance of wine, they believe that it became really and truly the blood of Christ, and that the priest in drinking it would make a sacrifice of Christ anew for the salvation of the souls of those who should witness and join in the ceremony.

"In the same manner a small round piece of bread, shaped like a large wafer, when consecrated by the priest's prayers, becomes, they think, really and truly the body of Christ; and the priest by eating it performs a sacrifice, just as he does by drinking the wine. When he has consecrated this wafer, he holds it up for a moment, that the people may look upon it; and they, in looking upon it, think they see a portion of the true body of Christ, which is about to be offered up by the priest as a sacrifice for their sins."

"Yes," said Rollo, "I remember when he held up the wafer. I did not know what it was."

"Did you not see that all the people bowed their heads just then," rejoined Mr. George, "and said something to themselves in a very reverent manner."

"Yes," said Rollo, "but I did not understand what it meant."

"Thus you see," continued Mr. George, "that the essential thing at a Catholic service like this, as they regard it, is the eating of the body and the drinking of the blood of Jesus Christ, as a new sacrifice for the sins of the people who are present and consenting in heart to the ceremony. There are a great many subordinate operations and rites. The assistant goes back and forth a great many times from one side of the altar to the other, stopping to bow and kneel every time he passes the crucifix. The priest makes a great deal of ceremony of wiping out the cup before he receives the wine. Then there is a long service, which he reads in a low voice, and there are many prayers which he offers, and he turns to various passages of the Scriptures, and reads portions here and there. The people do not hear any thing that he says and does, nor is it necessary, according to their ideas of the service, that they should do so; for they know very well that the priest is consecrating the bread or the wine, and changing it into the body and the blood of Christ, in order that it may be ready for the sacrifice. Then, when the wine is changed, the priest drinks it in a very solemn manner, raising it to his lips three several times, so as to take it in three portions. Then he holds the cup out to his assistant again, who pours a little water into it from his other vessel; and the priest then, after moving the cup round and round, to be sure that the water mixes itself well with the wine which was left on the inner service of the cup, drinks that too. He does this in order to make sure that no portion of the precious blood remains in the cup. He then wipes it out carefully with his napkin, and puts it away."

"Yes," said Rollo, "I saw all those things. And after he had got through, he covered the cup with a cloth, embroidered with gold, and carried it away."

"And after that," continued Rollo, "the assistant, with an extinguisher on the top of a tall pole, put out the candles, and then he went away."

"Yes," said Mr. George, and so the service was concluded.

"Thus you see," continued Mr. George, "that for all that the people come for, to such a service as that, it was not necessary that they should hear at all. There was not any thing to be said to them. There was only something to be done for them; and so long as it was done, and done properly, they standing by and consenting, it was not of much consequence whether they could see and hear or not. So the priest turned his face away from them towards the altar; and when he had any thing to say, he spoke the words in a very low and inaudible voice."

"It is impossible," said Rollo, after a short pause, "that the wine should become blood, and the wafer flesh, while they yet look just as they did before."

THE EMIGRANTS.

"True," said Mr. George, "it seems impossible to us, who hear of it for the first time, after we have grown up to years of discretion; but that does not prevent its being honestly believed by people that have been taught to consider it true from their earliest infancy."

"Do you suppose the priests themselves believe it?" asked Rollo.

"Yes," said Mr. George, "a great many of them undoubtedly do. We find, it is true, every where, that the most intelligent and well educated men will continue, all their lives, to believe very strange things, provided they were taught to believe them when they were very young; and provided, also, that their worldly interests are in any way concerned in their continuing to believe them."

Just at this time, Rollo's attention was attracted to what seemed to be an encampment on the roadside at a little distance before them. It was a family of emigrants that were going down the river, and had stopped to rest. The horses had been unharnessed, and were eating, and the wagon was surrounded with a family consisting of men, women, and children, who were sitting on the bank taking their suppers. Rollo wished very much that he understood German, so as to go and talk with them. But he did not, and so he contented himself with wishing them guten abend, which means good evening, as he went by.

He went on after this, without any farther adventure, to the village, and after attending church there, he returned with his uncle down along the bank of the river to the hotel.

Chapter IX.

Ehrenbreitstein

The people of the Rhine have not allowed all the old castles to go to ruin. Some have been carefully preserved from age to age, and never allowed to go out of repair. Others that had gone to decay, or had been destroyed in the wars, have been repaired and rebuilt in modern times, and are now in better condition than ever.

Some of the strongholds that have thus been restored are now great fortresses, held by the governors of the states and kingdoms that border on the river; others of them are fitted up as summer residences for the persons, whether princes or private people, that happen to own them. About midway between the beginning and the end of the mountainous region of the Rhine is a place where there are two very important works of this kind. One of them is far the largest and most important of all on the river. This is the Castle of Ehrenbreitstein. Ehrenbreitstein is not only a very strong and important fortification, but it guards a very important point.

This point is the place where the River Moselle, one of the principal branches of the Rhine, comes in. The valley of the Moselle is a very rich and fertile one, and in proportion to its extent is almost as valuable as that of the Rhine. The junction of the two rivers is the place for defending both of these valleys, and has consequently, in all ages of the world, been a very important post. The Romans built a town here, in the days of Julius Cæsar, and the town has continued to the present day. It is called Coblenz. The Romans named it originally Confluentes, which means the confluence; and this name, in the course of ages, has gradually become changed to Coblenz.

Coblenz is built on a three-cornered piece of flat land, exactly on the point where the two rivers come together. There is a bridge over the mouth of the Moselle where it comes into the Rhine, and another over the Rhine itself. The bridge over the Moselle is of stone, and was built a great many hundred years ago. That over the Rhine is what is called a bridge of boats.

A row of large and solid boats is anchored in the river, side by side, with their heads up the stream, and then the bridge is made by a platform which extends across from boat to boat, across the whole breadth of the stream.

Near the Coblenz side of the bridge there are two or three lengths of it which can be taken out when necessary, in order to let the steamers, or rafts, or tow boats, that may be coming up or down the river, pass through. Rollo was very much interested, while he remained at Coblenz, in looking out from the windows of his hotel, which faced the river, and seeing them open this bridge, to let the steamers and vessels pass through. A length of the bridge, consisting sometimes of two boats with the platform over it, and sometimes of three, would separate from the others, and float down the stream until it cleared itself from the rest of the bridge, and then would move by some mysterious means to one side, and so make an opening. Then, when the steamer, or whatever else it was, had passed through, the detached portion of the bridge would come back again slowly and carefully to its place.

Of course all the travel on the bridge would be interrupted during this operation; but as soon as the connection was again restored, the streams of people would immediately begin to move again over the bridge, as before.

Across the bridge, on the heights upon the other side, Rollo could see the great Castle of Ehrenbreitstein, together with an innumerable multitude of walls, parapets, bastions, towers, battlements, and other constructions pertaining to such a work.

One day Mr. George and Rollo went over to see this fortress. They were stopped a few minutes at the bridge, by a steamer going through. There was a large company of soldiers stopped too, part of the garrison of Ehrenbreitstein that had been over to attend a parade on the public square at Coblenz, and were now going home, so that Rollo was not sorry for the detention, as it gave him a fine opportunity to see the soldiers, and to examine the Prussian uniform. It consisted of a blue frock coat and white trousers, with an elegant brass-mounted helmet for a cap.

The way up to the castle was by a long and winding road, built up artificially on arches of solid masonry. This road was every where overlooked by walls, with portholes and embrasures for cannon, and all along it, at short distances, were immense gateways exceedingly massive and strong, which could all be shut in time of siege. When Mr. George and Rollo reached the top of the castle, they found a great esplanade there, surrounded with buildings for barracks, and for the storing of arms and provisions. The view from this esplanade was magnificent beyond description. You could see far up and down the River Rhine, and far up the Moselle, while all Coblenz, and the two bridges, and the town below the castle, and three other immense forts that stood on the other side of the river, were directly beneath.

Rollo went into some of the barracks, and also up to the top of the buildings. The buildings were all arched over above, and covered with earth ten feet deep, with grass growing on the top. The men were mowing this grass when Mr. George and Rollo were there. The object of this earth on the roofs of the buildings is to prevent the bombshells of the enemy from breaking down through the roofs and killing the men.

On the afternoon of the same day that Mr. George and Rollo visited Ehrenbreitstein, they went up the river a few miles in a boat to see a smaller castle, which has been repaired and changed into a private residence. The name of it is Stoltzenfels. They rode up the mountain that this castle was built upon on donkeys. The road was very good, but the place was so steep that it was necessary to make it twist and turn, in winding its way up, in the most extraordinary manner. In one place it actually went over itself by an arched bridge thrown across the ravine. In fact, this path was just like a corkscrew.

Rollo was exceedingly delighted with the castle of Stoltzenfels. A man who was there conducted him and his uncle, together with a small company of other visitors who arrived at the same time, all over it. It would be impossible to describe it, there were so many curious courts, and towers, and winding passage ways, and little gardens, and terraces, all built in a sort of nest among the rocks, of the most irregular and wildest character.

The rooms were all beautifully finished and furnished, and they were full of old relics of feudal times. The floors were of polished oak, and the visitors, when walking over them, wore over their boots and shoes great slippers made of felt, which were provided there for the purpose.

Chapter X.

Rollo's Letter

At one place where Mr. George and Rollo stopped to spend a night, Rollo wrote a letter to Jenny. It was as follows:—

St. Goar on the Rhine.}Friday Evening. }Dear Jenny: We have got into a very lonely place. I did not know there was such a lonely place on the Rhine. The name of it is St. Goar; but they pronounce it St. Gwar. The river is shut in closely by the mountains on both sides, and also above and below; so that it seems as if we were in a very deep valley, with a pond of water in the bottom of it.

Away across the river is a long row of white houses, crowded in between the edge of the water and the mountain. On the mountain above is an old ruined castle, called the Cat. There is another old ruin a few miles below, called the Mouse. I can see both of these ruins from my windows.

There is a little town on this side of the village too. We went out this morning to see it. It is very small, and the streets are very narrow. We came to the queerest old church you ever saw. It was all entangled up with other buildings, and there were so many arches, and flights of steps, and various courts all around it, that it was a long time before we could find out where the door was.

While we were looking about, a little girl came up and asked us something. We supposed she asked us whether we wished to see the church; so we said Ja, and then she ran away. Presently we saw a boy coming along, and he asked us something, and we said Ja; and then he ran away. We did not know what they meant by going away; but the fact was, they went to find some men who kept the keys. It seems there are two men who keep keys, and the girl went for one and the boy for the other; and so, after we had waited about five minutes under an arch which led to an old door, two men came with keys to let us in. Uncle George paid them both, because he said the second man that came looked disappointed. He paid the girl and the boy too; so he had four persons to pay; and when we got in, we found that it was nothing but a Protestant church, after all. I like the Catholic churches the best. They are a great deal the funniest.

We went to see the Catholic church afterwards. There was a monstrous old gallery all on one side of the church, and none on the other. Then there was an organ away up in a loft, and all sorts of old images and statues. I never saw such an old looking place.

As we walked along the streets, or rather the pathways between the houses, we could see the rocks and mountains away up over our heads, almost hanging over the town. They are very pretty rocks, being all green, with grapevines and bushes.

Close by the town too, up a long and very steep path, is a monstrous old ruin. The name of it is Rheinfels. I can see it from the balcony of my windows. Besides, uncle George and I went up to it this afternoon. It is nothing but old walls, and arches, and dark dungeons, all tumbling down. There was a little fence and a gate across the entrance, and the gate was locked. But there was a man who asked us something in German; but we could see it all just as well without going in; so we said Nein, which means no.

They say that a great many years ago the French took this castle, and then, to prevent its doing the enemy any good forever afterwards, they put a great deal of gunpowder into the cellars, and blew it up. I did not care much about the old ruins, but I should have liked very well to have seen them blow it up.

The waiter has just come to call us to go out and hear the echo, and so I must go. I will tell you about it afterwards.

The man played on a trumpet down on the bank of the river, and we could hear the echo from the rocks and mountains on the other side. He also fired a gun two or three times. After the gun was fired, for a few minutes all was still; but then there came back a sharp crack from the other shore, and then a long, rumbling sound from up the river and down the river, like a peal of distant thunder.

It is a gloomy place here after all, and I shall be glad when I get out of it; for the river is down in the bottom of such a deep gorge, that we cannot see out any where. There are some old castles about on the hills, and they look pretty enough at a distance; but when you get near them they are nothing but old walls all tumbling down. The vineyards are not pretty either. They are all on terraces kept up by long stone walls; and when you are down on the river, and look up to them, you cannot see any thing but the walls, with the edge of the vineyards, like a little green fringe, along on the top. But there is no great loss in this, for the vineyards are not pretty when you can see them. They look just like fields full of beans growing on short poles.

I shall be glad when we get out of this place; but uncle George says he is going to stay here all day to-morrow, to write letters and to bring up his journal. But never mind; I can have a pretty good time sitting on the steps that go down to the water, and seeing the vessels, and steamboats, and rafts go by.

Your affectionate cousin,Rollo.P.S. The Cat and the Mouse used to fight each other in old times, and the Mouse used to beat. Was not that funny?

Chapter XI.

The Raft

The morning after Rollo had finished the letter to Jenny, as recorded in the last chapter, his uncle George told him at breakfast time that he might amuse himself that day in any way he pleased.

"I shall be busy writing," said Mr. George, "nearly all the morning. It is such a still and quiet place here that I think I had better stay and finish up my writing. Besides, it must be an economical place, I think, and we can stay here a day cheaper than we can farther up the river, at the large towns."

"Shall we come to the large towns soon?" asked Rollo.

"Yes," replied his uncle. "This deep gorge only continues fifteen or twenty miles farther, and then we come out into open country, and to the region of large towns. You see there is no occasion for any other towns in this part of the Rhine than villages of vinedressers, except here and there a little city where a branch river comes in."

"Well," said Rollo, "I shall be glad when we get out. But I will go down to the shore, and play about there for a while."

Accordingly, as soon as Rollo had finished his breakfast, he went down to the shore.

The hotel faced the river, though there was a road outside of it, between it and the water. From the outer edge of the road there was a steep slope, leading down to the water's edge. This slope was paved with stones, to prevent the earth from being washed away by the water in times of flood. Here and there along this slope were steps leading down to the water. At the foot of these steps were boats, and opposite to them, in the road, there were boatmen standing in groups here and there, ready to take any body across the river that wished to go.

Rollo went down to the shore, and took his seat on the upper step of one of the stairways, and began to look about him over the water. There were two other boys sitting near by; but Rollo could not talk to them, for they knew only German.

Presently one of the boatmen came up to him, and pointing to a boat, asked him a question. Rollo did not understand what the man said, but he supposed that he was asking him if he did not wish for a boat. So Rollo said Nein, and the man went away.

There was a village across the river, in full view from where Rollo sat. This village consisted of a row of white stone houses facing the river, and extending along the margin of it, at the foot of the mountains. There seemed to be just room for them between the mountains and the shore. Among the houses was to be seen, here and there, the spire of an antique church, or an old tower, or a ruined wall. After sitting quietly on the steps until he had seen two steamers go down, and a fleet of canal boats from Holland towed up, Rollo took it into his head that it might be a good plan for him to go across the river. So he went in to ask his uncle George if he thought it would be safe for him to go.

"You will take a boatman?" said Mr. George.

"Yes," said Rollo.

"And how long shall you wish to be gone?"

"About an hour," said Rollo.

"Very well," said Mr. George, "you may go."

So Rollo went down to the shore again, and as he now began to look at the boats as if he wished to get into one of them, a man came to him again, and asked him the same question. Rollo said Ja. So the man went down to his boat, and drew it up to the lowest step of the stairs where Rollo was standing. Rollo got in, and taking his seat, pointed over to the other side of the river. The man then pushed off. The current was, however, very swift, and so the boatman poled the boat far up the stream before he would venture to put out into it; and then he was carried down a great way in going across.

When they reached the landing on the opposite shore, Rollo asked the man, "How much?" He knew what the German was for how much. The man said, "Two groschen." So Rollo took the two groschen from his pocket and paid him. Two groschen are about five cents.

Rollo walked about in the village where he had landed for nearly half an hour; and then, taking another boat on that side, he returned as he had come. On his way back he saw a great raft coming down. He immediately conceived the idea of taking a little sail on that raft, down the river. He wanted to see "how it would seem" to be on such an immense raft, and how the men managed it. So he went in to propose the plan to his uncle George. He said that he should like to go down the river a little way on the raft, and then walk back.

"Yes," said Mr. George, "or you might come up in the next steamer."

"So I might," said Rollo.

"I have no objection," said Mr. George.

"How far down may I go?" said Rollo.

"Why, you had better not go more than ten or fifteen miles," said Mr. George, "for the raft goes slowly,—probably not more than two or three miles an hour,—and it would take you four or five hours, perhaps, to go down ten miles. You would, however, come back quick in the steamer. Go down stairs and consider the subject carefully, and form your plan complete. Consider how you will manage to get on board the raft, and to get off again; and where you will stop to take the steamer, and when you will get home; and when you have planned it all completely, come to me again."

So Rollo went down, and after making various inquiries and calculations, he returned in about ten minutes to Mr. George, with the following plan.

"The waiter tells me," said he, "that the captain of the raft will take me down as far as I want to go, and set me ashore any where, in his boat, for two or three groschen, and that one of the boatmen here will take me out to the raft, when she comes by, for two groschen. A good place for me to stop would be Boppard, which is about ten or twelve miles below here. The raft will get there about two o'clock. Then there will be a steamer coming along by there at three, which will bring up here at four, just about dinner time. The waiter says that he will go out with me to the raft, and explain it all to the captain, because the captain would not understand me, as he only knows German."

![Rollo's Philosophy. [Air]](/covers_200/36364270.jpg)