полная версия

полная версияCab and Caboose: The Story of a Railroad Boy

The crowd slowly melted away; but before they left, everybody had heard one version or another of the story told to President Vanderveer in the dressing-room. Some believed Rod to be innocent of the charge brought against him, and some believed him guilty. Almost all of them said it was a pity that such races could not be won and lost honestly, and there must be some fire where there was so much smoke; and they told each other how they had noticed from the very first that something was wrong with Snyder Appleby’s wheel.

Major Appleby heard the story, first from President Vanderveer, and afterwards from his adopted son, who confirmed it by displaying the side of his face which was swollen and bruised from Rodman’s blow. Fully believing what Snyder told him, the Major became very angry. He declared that no such disgrace had ever before been brought to his house, and that the boy who was the cause of it could no longer be sheltered by his roof. In vain did people talk to him, and urge him to reflect before he acted. He had decided upon his course, and the more they advised him, the more determined he became not to be moved from it.

While he was thus storming and fuming outside the dressing-room, the members of the wheel club were holding a meeting behind its closed door. Did they believe Rodman Blake guilty of the act charged against him or did they not? The debate was a long and exciting one; but the question was finally decided in his favor. They did not believe him capable of doing anything so mean. They would make a thorough investigation of the affair, and aid him by every means in their power to prove his innocence.

This was the purport of the message sent to the young captain by the club secretary, Billy Bliss; but it was sent too late. The members had taken no note of time in the heat of their discussion, and the hour named by Rodman had already elapsed before Billy Bliss started on his errand. The fellows did not think a few minutes more or less would make any difference, though they urged the secretary to hurry and deliver his message as quickly as possible. A few minutes however did make all the difference in the world to Rod Blake. With him an hour meant exactly sixty minutes; and when Billy Bliss reached Major Appleby’s house the boy whom he sought was nowhere to be found.

Major Appleby and his adopted son walked home together, the former full of wrath at what he believed to be the disgraceful action of his nephew, and the latter secretly rejoicing at it. On reaching the house, the Major went at once to Rodman’s room where he found the boy gazing from the window, with a hard, defiant, expression on his face. He was longing for a single loving word; for a mother’s sympathetic ear into which he might pour his griefs; but his pride was prepared to withstand any harshness, as well as to resent the faintest suspicion of injustice.

“Well, sir,” began the Major, “what have you to say for yourself? and how do you explain this disgraceful affair?”

“I cannot explain it, Uncle; but–”

“That will do, sir. If you cannot explain it, I want to hear nothing further. What I do want, however, is that you shall so arrange your future plans that you may no longer be dependent on my roof for shelter. Here is sufficient money for your immediate needs. As my sister’s child you have a certain claim on me. This I shall be willing to honor to the extent of providing you against want, whenever you have settled upon your mode of life, and choose to favor me with your future address. The sooner you can decide upon your course of action the better.” Thus saying the kind-hearted, impetuous, and wrong-headed old Major laid a roll of bills on the table, and left the room.

Fifteen minutes later, or five minutes before Billy Bliss reached the house, Rod Blake also left the room. The roll of bills lay untouched where his uncle had placed it, and he carried only his M. I. P. or bicycle travelling bag, containing the pictures of his parents, a change of underclothing, and a few trifles that were absolutely his own. He passed out of the house by a side door, and was seen but by one person as he plunged into the twilight shadows of the park. Thus, through the gathering darkness, the poor boy, proud, high-spirited, and, as he thought, friendless, set forth alone, to fight his battle with the world.

CHAPTER V.

CHOOSING A CAREER

As Rod Blake, heavy-hearted, and weary, both mentally and physically from his recent struggles, left his uncle’s house, he felt utterly reckless, and paid no heed to the direction his footsteps were taking. His one idea was to get away as quickly, and as far as possible, from those who had treated him so cruelly. “If only the fellows had stood by me,” he thought, “I might have stayed and fought it out. But to have them go back on me, and take Snyder’s word in preference to mine, is too much.”

Had the poor boy but known that Billy Bliss was even then hastening to bear a message of good-will and confidence in him from the “fellows” how greatly his burden of trial would have been lightened. But he did not know, and so he pushed blindly on, suffering as much from his own hasty and ill-considered course of action, as from the more deliberate cruelty of his adopted cousin. At length he came to the brow of a steep slope leading down to the railroad, the very one of which Eltje’s father was president. The railroad had always possessed a fascination for him, and he had often sat on this bank watching the passing trains, wondering at their speed, and speculating as to their destinations. He had frequently thought he should like to lead the life of a railroad man, and had been pleased when the fellows called him “Railroad Blake” on account of his initials. Now, this idea presented itself to him again more strongly than ever.

An express train thundered by. The ruddy glow from the furnace door of its locomotive, which was opened at that moment, revealed the engineman seated in the cab, with one hand on the throttle lever, and peering steadily ahead through the gathering gloom. What a glorious life he led! So full of excitement and constant change. What a power he controlled. How easy it was for him to fly from whatever was unpleasant or trying. As these thoughts flashed through the boy’s mind, the red lights at the rear of the train seemed to blink pleasantly at him, and invite him to follow them.

“I will,” he cried, springing to his feet. “I will follow wherever they may lead me. Why should I not be a railroad man as well as another? They have all been boys and all had to begin some time.”

At this moment he was startled by a sound of a voice close beside him saying, “Supper is ready, Mister Rod.” It was Dan the stable boy; and, as Rodman asked him, almost angrily, how he dared follow him without orders, and what he was spying out his movements for, he replied humbly: “I ain’t a-spying on you, Mister Rod, and I only followed you to tell you supper was ready, ’cause I thought maybe you didn’t know it.”

“Well, I didn’t and it makes no difference whether I did or not,” said Rod. “I have left my uncle’s house for good and all, Dan, and there are no more suppers in it for me.”

“I was afeard so! I was afeard so, Mister Rod,” exclaimed the boy with a real distress in his voice, “an’ to tell the truth that’s why I came after you. I couldn’t a-bear to have you go without saying good-by, and I thought maybe, perhaps, you’d let me go along with you. Please do, Mister Rod. I’ll work for you and serve you faithfully, an’ I’d a heap rather go on a tramp, or any place along with you, than stay here without you. Please, Mister Rod.”

“No, Dan, it would be impossible to take you with me,” said Rodman, who was deeply touched by this proof of his humble friend’s loyalty. “It will be all I can do to find work for myself; but I’m grateful to you all the same for showing that you still think well of me. It’s a great thing, I can tell you, for a fellow in my position to know that he leaves even one friend behind him when he is forced to go away from his only home.”

“You leaves a-plenty of them—a-plenty!” interrupted the stable boy eagerly. “I heerd Miss Eltje telling her father that it was right down cruel not to give you the cup, an’ that you couldn’t do a thing, such as they said, any more than she could, or he could himself. An’ her father said no more did he believe you could, an’ you’d come out of it all right yet. Miss Eltje was right up an’ down mad about it, she was. Oh, I tell you, Mister Rod, you’ve got a-plenty of friends; an’ if you’ll only stay you’ll find ’em jest a-swarmin’.”

At this Rodman laughed outright, and said: “Dan, you are a fine fellow, and you have done me good already. Now what I want you to do is just to stay here and discover some more friends for me. I will manage to let you know what I am doing; but you must not tell anybody a word about me, nor where I am, nor anything. Now good-by, and mind, don’t say a word about having seen me, unless Miss Eltje should happen to ask you. If she should, you might say that I shall always remember her, and be grateful to her for believing in me. Good-by.”

With this Rod plunged down the steep bank to the railroad track, and disappeared in the darkness. He went in the direction of the next station to Euston, about five miles away, as he did not wish to be recognized when he made the attempt to secure a ride on some train to New York. It was to be an attempt only; for he had not a cent of money in his pockets, and had no idea of how he should obtain the coveted ride. In addition to being penniless, he was hungry, and his hunger was increased tenfold by the knowledge that he had no means of satisfying it. Still he was a boy with unlimited confidence in himself. He always had fallen on his feet; and, though this was the worse fix in which he had ever found himself, he had faith that he would come out of it all right somehow. His heart was already so much lighter since he had learned from Dan that some of his friends, and especially Eltje Vanderveer, still believed in him, that his situation did not seem half so desperate as it had an hour before.

Rod was already enough of a railroad man to know that, as he was going east, he must walk on the west bound track. By so doing he would be able to see trains bound west, while they were still at some distance from him, and would be in no danger from those bound east and overtaking him.

When he was about half a mile from the little station, toward which he was walking, he heard the long-drawn, far-away whistle of a locomotive. Was it ahead of him or behind? On account of the bewildering echoes he could not tell. To settle the question he kneeled down, and placed his ear against one of rails of the west bound track. It was cold and silent. Then he tried the east bound track in the same way. This rail seemed to tingle with life, and a faint, humming sound came from it. It was a perfect railroad telephone, and it informed the listener as plainly as words could have told him, that a train was approaching from the west.

He stopped to note its approach. In a few minutes the rails of the east bound track began to quiver with light from the powerful reflector in front of its locomotive. Then they stretched away toward the oncoming train in gleaming bands of indefinite length, while the dazzling light seemed to cut a bright pathway between walls of solid blackness for the use of the advancing monster. As the bewildering glare passed him, Rod saw that the train was a long, heavy-laden freight, and that some of its cars contained cattle. He stood motionless as it rushed past him, shaking the solid earth with its ponderous weight, and he drew a decided breath of relief at the sight of the blinking red eyes on the rear platform of its caboose. How he wished he was in that caboose, riding comfortably toward New York, instead of plodding wearily along on foot, with nothing but uncertainties ahead of him.

CHAPTER VI.

SMILER, THE RAILROAD DOG

As Rod stood gazing at the receding train he noticed a human figure step from the lighted interior of the caboose, through the open doorway, to the platform, apparently kick at something, and almost instantly return into the car. At the same time the boy fancied he heard a sharp cry of pain; but was not sure. As he resumed his tiresome walk, gazing longingly after the vanishing train lights, he saw another light, a white one that moved toward him with a swinging motion, close to the ground. While he was wondering what it was, he almost stumbled over a small animal that stood motionless on the track, directly in front of him. It was a dog. Now Rod dearly loved dogs, and seemed instinctively to know that this one was in some sort of trouble. As he stopped to pat it, the creature uttered a little whine, as though asking his sympathy and help. At the same time it licked his hand.

While he was kneeling beside the dog and trying to discover what its trouble was, the swinging white light approached so closely that he saw it to be a lantern, borne by a man who, in his other hand, carried a long-handled iron wrench. He was the track-walker of that section, who was obliged to inspect every foot of the eight miles of track under his charge, at least twice a day; and the wrench was for the tightening of any loose rail joints that he might discover.

“Hello!” exclaimed this individual as he came before the little group, and held his lantern so as to get a good view of them. “What’s the matter here?”

“I have just found this dog,” replied Rod, “and he seems to be in pain. If you will please hold your light a little closer perhaps I can see what has happened to him.”

The man did as requested, and Rod uttered an exclamation of pleasure as the light fell full upon the dog; for it was the finest specimen of a bull terrier he had ever seen. It was white and brindled, its chest was of unusual breadth, and its square jaws indicated a tenacity of purpose that nothing short of death itself could overcome. Now one of its legs was evidently hurt, and it had an ugly cut under the left ear, from which blood was flowing. Its eyes expressed an almost human intelligence; and, as it looked up at Rod and tried to lick his face, it seemed to say, “I know you will be my friend, and I trust you to help me.” About its neck was a leathern collar, bearing a silver plate, on which was inscribed: “Be kind to me, for I am Smiler the Railroad Dog.”

“I know this dog,” exclaimed the track-walker, as he read these words, “and I reckon every railroad man in the country knows him; or at any rate has heard of him. He used to belong to Andrew Dean, who was killed when his engine went over the bank at Hager’s two years ago. He thought the world of the dog, and it used to travel with him most always; only once in a while it would go visiting on some of the other engines. It was off that way when Andrew got killed, and since then it has travelled all over the country, like as though it was hunting for its old master. The dog lives on trains and engines, and railroad men are always glad to see him. Some of them got up this collar for him a while ago. Why, Smiler, old dog, how did you come here in this fix? I never heard of you getting left or falling off a train before.”

“I think he must have come from the freight that just passed us,” said Rod, “and I shouldn’t wonder,” he added, suddenly recalling the strange movements of the figure he had seen appear for an instant at the caboose door, “if he was kicked off.” Then he described the scene of which he had caught a glimpse as the freight train passed him.

“I’d like to meet the man who’d dare do such a thing,” exclaimed the track-walker. “If I wouldn’t kick him! He’d dance to a lively tune if any of us railroad chaps got hold of him, I can tell you. It must have been an accident, though; for nobody would hurt Smiler. Now I don’t know exactly what to do. Smiler can’t be left here, and I’m afraid he isn’t able to walk very far. If I had time I’d carry him back to the freight. She’s side-tracked only a quarter of a mile from here, waiting for Number 8 to pass. I’m due at Euston inside of an hour, and I don’t dare waste any more time.”

“I’ll take him if you say so,” answered Rod, who had been greatly interested in the dog’s history. “I believe I can carry him that far.”

“All right,” replied the track-walker. “I wish you would. You’ll have to move lively though; for if Number 8 is on time, as she generally is, you haven’t a moment to lose.”

“I’ll do my best,” said the boy, and a moment later he was hurrying down the track with his M. I. P. bag strapped to his shoulders, and with the dog so strangely committed to his care, clasped tightly in his arms. At the same time the track-walker, with his swinging lantern, was making equally good speed in the opposite direction. As Rod rounded a curve, and sighted the lights of the waiting freight train, he heard the warning whistle of Number 8 behind him, and redoubled his exertions. He did not stop even as the fast express whirled past him, though he was nearly blinded by the eddying cloud of dust and cinders that trailed behind it. But, if Number 8 was on time, so was he. Though Smiler had grown heavy as lead in his aching arms, and though his breath was coming in panting gasps, he managed to climb on the rear platform of the caboose, just as the freight was pulling out. How glad he was at that moment of the three weeks training he had just gone through with. It had won him something, even if his name was not to be engraved on the railroad cup of the Steel Wheel Club.

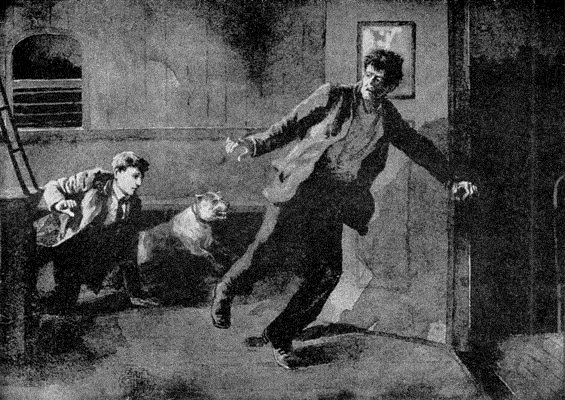

As the boy stood in the rear doorway of the caboose, gazing doubtfully into its interior, a young fellow who looked like a tramp, and who had been lying on one of the cushioned lockers, or benches, that ran along the sides of the car, sprang to his feet with a startled exclamation. At the same moment Smiler drew back his upper lip so as to display a glistening row of teeth, and, uttering a deep growl, tried to escape from Rod’s arms.

“What are you doing in this car! and what do you mean by bringing that dog in here?” cried the fellow angrily, at the same time advancing with a threatening gesture. “Come, clear out of here or I’ll put you out,” he added. The better to defend himself, if he should be attacked, the boy dropped the dog; and, with another fierce growl, forgetful of his hurts, Smiler flew at the stranger’s throat.

CHAPTER VII.

ROD, SMILER, AND THE TRAMP

“Help! Murder! Take off your dog!” yelled the young tramp, throwing up his arm to protect his face from Smiler’s attack, and springing backward. In so doing he tripped and fell heavily to the floor, with the dog on top of him, growling savagely, and tearing at the ragged coat-sleeve in which his teeth were fastened. Fearful lest the dog might inflict some serious injury upon the fellow, Rodman rushed to his assistance. He had just seized hold of Smiler, when a kick from the struggling tramp sent his feet flying from under him, and he too pitched headlong. There ensued a scene which would have been comical enough to a spectator, but which was anything but funny to those who took part in it. Over and over they rolled, striking, biting, kicking, and struggling. The tramp was the first to regain his feet; but almost at the same instant Smiler escaped from Rod’s embrace, and again flew at him. They had rolled over the caboose floor until they were close to its rear door; and now, with a yell of terror, the tramp darted through it, sprang from the moving train, and disappeared in the darkness, leaving a large piece of his trousers in the dog’s mouth. Just then the forward door was opened, and two men with lanterns on their arms, entered the car.

They were Conductor Tobin, and rear-brakeman Joe, his right-hand man, who had just finished switching their train back on the main track, and getting it again started on its way toward New York. At the sight of Rod, who was of course a perfect stranger to them, sitting on the floor, hatless, covered with dust, his clothing bearing many signs of the recent fray, and ruefully feeling of a lump on his forehead that was rapidly increasing in size, and of Smiler whose head was bloody, and who was still worrying the last fragment of clothing that the tramp’s rags had yielded him, they stood for a moment in silent bewilderment.

“Well, I’ll be blowed!” said Conductor Tobin at length.

“Me too,” said Brakeman Joe, who believed in following the lead of his superior officer.

“May I inquire,” asked Conductor Tobin, seating himself on a locker close to where Rod still sat on the floor, “May I inquire who you are? and where you came from? and how you got here? and what’s happened to Smiler? and what’s came of the fellow we left sleeping here a few minutes ago? and what’s the meaning of all this business, anyway?”

“Yes, we’d like to know,” said the Brakeman, taking a seat on the opposite locker, and regarding the boy with a curiosity that was not unmixed with suspicion. Owing to extensive dealings with tramps, Brakeman Joe was very apt to be suspicious of all persons who were dirty, and ragged, and had bumps on their foreheads.

“The trouble is,” replied Rod, looking first at Conductor Tobin and then at Brakeman Joe, “that I don’t know all about it myself. Nobody does except the fellow who just left here in such a hurry, and Smiler, who can’t tell.”

Here the dog, hearing his name mentioned, dragged himself rather stiffly to the boy’s side; for now that the excitement was over, his hurts began to be painful again, and licked his face.

SMILER DRIVES OFF THE TRAMP.—(PAGE 41.)

“Well, you must be one of the right sort, at any rate,” said Conductor Tobin, noting this movement, “for Smiler is a dog that doesn’t make friends except with them as are.”

“He knows what’s what, and who’s who,” added Brakeman Joe, nodding his head. “Don’t you, Smiler, old dog?”

“My name,” continued the boy, “is R. R. Blake.”

“Railroad Blake?” interrupted Conductor Tobin inquiringly.

“Or ‘Runaway Blake’?” asked Brakeman Joe who, still somewhat suspicious, was studying the boy’s face and the M. I. P. bag attached to his shoulders.

“Both,” answered Rod, with a smile. “The boys where I live, or rather where I did live, often call me ‘Railroad Blake,’ and I am a runaway. That is, I was turned away first, and ran away afterwards.”

Then, as briefly as possible, he gave them the whole history of his adventures, beginning with the bicycle race, and ending with the disappearance of the young tramp through the rear door of the caboose in which they sat. Both men listened with the deepest attention, and without interrupting him save by occasional ejaculations, expressive of wonder and sympathy.

“Well, I’ll be blowed!” exclaimed Conductor Tobin, when he had finished; while Brakeman Joe, without a word, went to the rear door and examined the platform, with the hope, as he afterwards explained, of finding there the fellow who had kicked Smiler off the train, and of having a chance to serve him in the same way. Coming back with a disappointed air, he proceeded to light a fire in the little round caboose stove, and prepare a pot of coffee for supper, leaving Rodman’s case to be managed by Conductor Tobin as he thought best.

The latter told the boy that the young tramp, as they called him, was billed through to New York, to look after some cattle that were on the train; but that he was a worthless, ugly fellow, who had not paid the slightest attention to them, and whose only object in accepting the job was evidently to obtain a free ride in the caboose. Smiler, whom he had been delighted to find on the train when it was turned over to him, had taken a great dislike to the fellow from the first. He had growled and shown his teeth whenever the tramp moved about the car, and several times the latter had threatened to teach him better manners. When he and Brakeman Joe went to the forward end of the train, to make ready for side-tracking it, they left the dog sitting on the rear platform of the caboose, and the tramp apparently asleep, as Rod had found him, on one of the lockers. He must have taken advantage of their absence to deal the dog the cruel kick that cut his ear, and landed him, stunned and bruised, on the track where he had been discovered.

“I’m glad he’s gone,” concluded Conductor Tobin, “for if he hadn’t left, we would have fired him for what he did to Smiler. We won’t have that dog hurt on this road, not if we know it. It won’t hurt him to have to walk to New York, and I don’t care if he never gets there. What worries me, though, is who’ll look after those cattle, and go down to the stock-yard with them, now that he’s gone.”