полная версия

полная версияDark Hollow

"Possibly because his victim was my friend and lifelong companion. A judge fears his own prejudices."

"Possibly; but you had another reason, judge; a reason which justified you in your own eyes at the time and which justifies you in mine now and always. Am I not right? This is no court-room; the case is one of the past; it can never be reopened; the prisoner is dead. Answer me then, as one sorrowing mortal replies to another, hadn't you another reason?"

The judge, panoplied though he was or thought he was, against all conceivable attack, winced at this repetition of a question he had hoped to ignore, and in his anxiety to hide this involuntary betrayal of weakness, allowed his anger to have full vent, as he cried out in no measured terms:

"What is the meaning of all this? What are you after? Why are you raking up these bygones which only make the present condition of affairs darker and more hopeless? You say that you know some way of making the match between your daughter and my son feasible and proper. I say that nothing can do this. Fact—the sternest of facts is against it. If you found a way, I shouldn't accept it. Oliver Ostrander, under no circumstances and by means of no sophistries, can ever marry the daughter of John Scoville. I should think you would see that for yourself."

"But if John should be proved to have suffered wrongfully? If he should be shown to have been innocent?"

"Innocent?"

"Yes. I have always had doubts of his guilt, even when circumstances bore most heavily against him; and now, as I look back upon the trial and remember certain things, I feel sure that you had doubts of it, yourself."

His rebuke was quick, instant. With a force and earnestness which recalled the court-room he replied:

"Madam, your hopes and wishes have misled you. Your husband was a guilty man; as guilty a man as any judge ever passed sentence upon."

"Oh!" she wailed forth, reeling heavily back and almost succumbing to the shock, she had so thoroughly convinced herself that what she said was true. But hers was a courageous soul. She rallied instantly and approaching him again with face uncovered and her whole potent personality alive with magnetism, she retorted:

"You say that, eye to my eye, hand on my hand, heart beating with my heart above the grave of our children's mutual happiness?"

"I do."

Convinced; for there was no wavering in his eye, no trembling in the hand she had clasped; convinced but ready notwithstanding to repudiate her own convictions, so much of the mother-passion, if not the wife's, tugged at her heart, she remained immovable for a moment, waiting for the impossible, hoping against hope for a withdrawal of his words and the reillumination of hope. Then her hand fell away from his; she gave a great sob, and, lowering her head, muttered:

"John Scoville smote down Algernon Etheridge! O God! O God! what horror!"

A sigh from her one auditor welled up in the silence, holding a note which startled her erect and brought back a memory which drove her again into passionate speech:

"But he swore the day I last visited him in the prison, with his arms pressed tight about me and his eye looking straight into mine as you are looking now, that he never struck that blow. I did not believe him then, there were too many dark spots in my memory of old lies premeditated and destructive of my happiness; but I believed him later, AND I BELIEVE HIM NOW."

"Madam, this is quite unprofitable. A jury of his peers condemned him as guilty and the law compelled me to pass sentence upon him. That his innocent child should be forced, by the inexorable decrees of fate, to suffer for a father's misdoing, I regret as much, perhaps more, than you do; for my son—beloved, though irreconcilably separated from me—suffers with her, you say. But I see no remedy;—NO REMEDY, I repeat. Were Oliver to forget himself so far as to ignore the past and marry Reuther Scoville, a stigma would fall upon them both for which no amount of domestic happiness could ever compensate. Indeed, there can be no domestic happiness for a man and woman so situated. The inevitable must be accepted. Madam, I have said my last word."

"But not heard mine," she panted. "For me to acknowledge the inevitable where my daughter's life and happiness are concerned would make me seem a coward in my own eyes. Helped or unhelped, with the sympathy or without the sympathy of one who I hoped would show himself my friend, I shall proceed with the task to which I have dedicated myself. You will forgive me, judge. You see that John's last declaration of innocence goes farther with me than your belief, backed as it is by the full weight of the law."

Gazing at her as at one gone suddenly demented, he said:

"I fail to understand you, Mrs.—I will call you Mrs. Averill. You speak of a task. What task?"

"The only one I have heart for: the proving that Reuther is not the child of a wilful murderer; that another man did the deed for which he suffered. I can do it. I feel confident that I can do it; and if you will not help me—"

"Help you! After what I have said and reiterated that he is guilty, GUILTY, GUILTY?"

Advancing upon her with each repetition of the word, he towered before her, an imposing, almost formidable figure. Where was her courage now? In what pit of despair had it finally gone down? She eyed him fascinated, feeling her inconsequence and all the madness of her romantic, ill-digested effort, when from somewhere in the maze of confused memories there came to her a cry, not of the disappointed heart but of a daughter's shame, and she saw again the desperate, haunted look with which the stricken child had said in answer to some plea, "A criminal's daughter has no place in this world but with the suffering and the lost"; and nerved anew, she faced again his anger which might well be righteous, and with almost preternatural insight, boldly declared:

"You are too vehement to quite convince me, Judge Ostrander. Acknowledge it or not, there is more doubt than certainty in your mind; a doubt which ultimately will lead you to help me. You are too honest not to. When you see that I have some reason for the hopes I express, your sense of justice will prevail and you will confide to me the point untouched or the fact unmet, which has left this rankling dissatisfaction to fester in your mind. That known, my way should broaden;—a way, at the end of which I see a united couple—my daughter and your son. Oh, she is worthy of him—" the woman broke forth, as he made another repellent and imperative gesture. "Ask any one in the town where we have lived."

Abruptly, and without apology for his rudeness, Judge Ostrander again turned his back and walked away from her to an old-fashioned bookcase which stood in one corner of the room. Halting mechanically before it, he let his eyes roam up and down over the shelves, seeing nothing, as she was well aware, but weighing, as she hoped, the merits of the problem she had propounded him. She was, therefore, unduly startled when with a quick whirl about which brought him face to face with her once more, he impetuously asked:

"Madam, you were in my house this morning. You came in through a gate which Bela had left unlocked. Will you explain how you came to do this? Did you know that he was going down street, leaving the way open behind him? Was there collusion between you?"

Her eyes looked up clearly into his. She felt that she had nothing to disguise or conceal.

"I had urged him to do this, Judge Ostrander. I had met him more than once in the street when he went out to do your errands, and I used all my persuasion to induce him to give me this one opportunity of pleading my cause with you. He was your devoted servant, he showed it in his death, but he never got over his affection for Oliver. He told me that he would wake oftentimes in the night feeling about for the boy he used to carry in his arms. When I told him—"

"Enough! He knew who you were then?"

"He remembered me when I lifted my veil. Oh, I know very well that I had not the right to influence your own man to disobey your orders. But my cause was so pressing and your seclusion seemingly so arbitrary. How could I dream that your nerves could not bear any sudden shock? or that Bela—that giant among negroes—would be so affected by his emotions that he would not see or hear an approaching automobile? You must not blame me for these tragedies; and you must not blame Bela. He was torn by conflicting duties, and only yielded because of his great love for the absent."

"I do not blame Bela."

Startled, she looked at him with wondering eyes. There was a brooding despair in his tone which caught at her heart, and for an instant made her feel the full extent of her temerity. In a vain endeavour to regain her confidence, she falteringly remarked.

"I had listened to what folks said. I had heard that you would receive nobody; talk to nobody. Bela was my only resource."

"Madam, I do not blame YOU."

He was scrutinising her keenly and for the first time understandingly. Whatever her station past or present, she was certainly no ordinary woman, nor was her face without beauty, lit as it was by passion and every ardour of which a loving woman is capable. No man would be likely to resist it unless his armour were thrice forged. Would he himself be able to? He began to experience a cold fear,—a dread which drew a black veil over the future; a blacker veil than that which had hitherto rested upon it.

But his face showed nothing. He was master of that yet. Only his tone. That silenced her. She was therefore scarcely surprised when, with a slight change of attitude which brought their faces more closely together, he proceeded, with a piercing intensity not to be withstood:

"When you entered my house this morning, did you come directly to my room?"

"Yes. Bela told me just how to reach it."

"And when you saw me indisposed—unable, in fact, to greet you—what did you do then?"

With the force and meaning of one who takes an oath, she brought her hand, palm downward on the table before her, as she steadily replied:

"I flew back into the room through which I had come, undecided whether to fly the house or wait for what might happen to you, I had never seen any one in such an attack before, and almost expected to hear you fall forward to the floor. But when you did not and the silence, which seemed so awful, remained unbroken, I pulled the curtain aside and looked in again. There was no change in your posture; and, alarmed now for your sake rather than for my own, I did not dare to go till Bela came back. So I stayed watching."

"Stayed where?"

"In a dark corner of that same room. I never left it till the crowd came in. Then I slid out behind them."

"Was the child with you—at your side I mean, all this time?"

"I never let go her hand."

"Woman, you are keeping nothing back?"

"Nothing but my terror at the sight of Bela running in all bloody to escape the people pressing after him. I thought then that I had been the death of servant as well as master. You can imagine my relief when I heard that yours was but a passing attack."

Sincerity was in her manner and in her voice. The judge breathed more easily, and made the remark:

"No one with hearing unimpaired can realise the suspicion of the deaf, nor can any one who is not subject to attacks like mine conceive the doubts with which a man so cursed views those who have been active about him while the world to him was blank."

Thus he dismissed the present subject, to surprise her by a renewal of the old one.

"What are your reasons," said he, "for the hopes you have just expressed? I think it your duty to tell me before we go any further."

It was an acknowledgment, uttered after his own fashion, of the truth of her plea and the correctness of her woman's insight. She contemplated his face anew, and wondered that the dart she had so inconsiderately launched should have found the one weak joint in this strong man's armour. But she made no immediate reply, rather stopped to ponder, finally saying, with drooped head and nervously working fingers:

"Excuse me for to-night. What I have to tell—or rather, what I have to show you,—requires daylight." Then, as she became conscious of his astonishment, added falteringly:

"Have you any objection to meeting me to-morrow on the bluff overlooking Dark–"

The voice of the clock, and that only! Tick! Tick! Tick! Tick! That only! Why then had she felt it impossible to finish her sentence? The judge was looking at her; he had not moved; nor had an eyelash stirred, but the rest of that sentence had stuck in her throat, and she found herself standing as immovably quiet as he.

Then she remembered. He had loved Algernon Etheridge. Memory still lived. The spot she had mentioned was a horror to him. Weakly she strove to apologise.

"I am sorry," she began, but he cut her short at once.

"Why there?" he asked.

"Because"—her words came slowly, haltingly, as she tremulously, almost fearfully, felt her way with him—"because—there—is—no—other place—where—I can make—my point."

He smiled. It was his first smile in years and naturally was a little constrained,—and to her eyes at least, almost more terrifying than his frown.

"You have a point, then, to make?"

"A good one."

He started as if to approach her, and then stood stock-still.

"Why have you waited till NOW?" he called out, forgetful that they were not alone in the house, forgetful apparently of everything but his surprise and repulsion. "Why not have made use of this point before it was too late? You were at your husband's trial; you were even on the witness-stand?"

She nodded, thoroughly cowed at last both by his indignation and the revelation contained in this question of the judicial mind—"Why now, when the time was THEN?"

Happily, she had an answer.

"Judge Ostrander, I had a reason for that too; and, like my point, it is a good one. But do not ask me for it to-night. To-morrow I will tell you everything. But it will have to be in the place I have mentioned. Will you come to the bluff where the ruins are one-half hour before sunset? Please, be exact as to the time. You will see why, if you come."

He leaned across the table—they were on opposite sides of it—and plunging his eyes into hers stood so, while the clock ticked out one slow minute more, then he drew back, and remarking with an aspect of gloom but with much less appearance of distrust:

"A very odd request, madam. I hope you have good reason for it;" adding, "I bury Bela to-morrow and the cemetery is in this direction. I will meet you where you say and at the hour you name."

And, regarding him closely as he spoke, she saw that for all the correctness of his manner and the bow of respectful courtesy with which he instantly withdrew, that deep would be his anger and unquestionable the results to her if she failed to satisfy him at this meeting of the value of her POINT in reawakening justice and changing public opinion.

IX

EXCERPTS

One of the lodgers at the Claymore Inn had great cause for complaint the next morning. A restless tramping over his head had kept him awake all night. That it was intermittent had made it all the more intolerable. Just when he thought it had stopped, it would start up again,—to and fro, to and fro, as regular as clockwork and much more disturbing.

But the complaint never reached Mrs. Averill. The landlady had been restless herself. Indeed, the night had been one of thought and feeling to more than one person in whom we are interested. The feeling we can understand; the thought—that is, Mrs. Averill's thought—we should do well to follow.

The one great question which had agitated her was this: Should she trust the judge? Ever since the discovery which had changed Reuther's prospects, she had instinctively looked to this one source for aid and sympathy. Her reasons she has already given. His bearing during the trial, the compunction he showed in uttering her husband's sentence were sufficient proof to her that for all his natural revulsion against the crime which had robbed him of his dearest friend, he was the victim of an undercurrent of sympathy for the accused which could mean but one thing—a doubt of the prisoner's actual guilt.

But her faith had been sorely shaken in the interview just related. He was not the friend she had hoped to find. He had insisted upon her husband's guilt, when she had expected consideration and a thoughtful recapitulation of the evidence; and he had remained unmoved, or but very little moved, by the disappointment of his son—his only remaining link to life.

Why? Was the alienation between these two so complete as to block out natural sympathy? Had the separation of years rendered them callous to every mutual impression? She dwelt in tenderness upon the bond uniting herself and Reuther and could not believe in such unresponsiveness. No parent could carry resentment or even righteous anger so far as that. Judge Ostrander might seem cold,—both manner and temper would naturally be much affected by his unique and solitary mode of life,—but at heart he must love Oliver. It was not in nature for it to be otherwise. And yet—

It was at this point in her musing that there came one of the breaks in her restless pacing. She was always of an impulsive temperament, and always giving way to it. Sitting down before paper and ink she wrote the following lines:

My Darling if Unhappy Child:

I know that this sudden journey on my part must strike you as cruel, when, if ever, you need your mother's presence and care. But the love I feel for you, my Reuther, is deep enough to cause you momentary pain for the sake of the great good I hope to bring you out of this shadowy quest. I believe, what I said to you on leaving, that a great injustice was done your father. Feeling so, shall I remain quiescent and see youth and love slip from you, without any effort on my part to set this matter straight? I cannot. I have done you the wrong of silence when knowledge would have saved you shock and bitter disillusion, but I will not add to my fault the inertia of a cowardly soul. Have patience with me, then; and continue to cherish those treasures of truth and affection which you may one day feel free to bestow once more upon one who has a right to each and all of them.

This is your mother's prayer.

DEBORAH SCOVILLE.It was not easy for her to sign herself thus. It was a name which she had tried her best to forget for twelve long, preoccupied years. But how could she use any other in addressing her daughter who had already declared her intention of resuming her father's name, despite the opprobrium it carried and the everlasting bar it must in itself raise between herself and Oliver Ostrander?

Deborah Scoville!

A groan broke from her lips as she rapidly folded that name in, and hid it out of sight in the envelope she as rapidly addressed.

But her purpose had been accomplished, or would be when once this letter reached Reuther. With these words in declaration against her she could not retreat from the stand she had therein taken. It was another instance of burning one's ships upon disembarking, and the effect made upon the writer showed itself at once in her altered manner. Henceforth, the question should be not what awaited her, but how she should show her strength in face of the opposition she now expected to meet from this clear-minded, amply equipped lawyer and judge she had called to her aid.

"A task for his equal, not for an ignorant, untried woman like myself," she thought; and, following another of her impulses, she leaped from her seat at the table and rushed across to her dresser on which she placed two candles, one at her right and another at her left. Then she sat down between them and in the stillness of midnight surveyed herself in the glass, as she might survey the face of a stranger.

What did she see? A countenance no longer young, and yet with some of the charm of youth still lingering in the brooding eyes and in the dangerous curves of a mobile and expressive mouth. But it was not for charm she was looking, but for some signs of power quite apart from that of sex. Did her face express intellect, persistence and, above all, courage? The brow was good;—she would so characterise it in another. Surely a woman with such a forehead might do something even against odds. Nor was her chin weak; sometimes she had thought it too pronounced for beauty; but what had she to do with beauty now? And the neck so proudly erect! the heaving breast! the heart all aflame! Defeat is not for such; or only such defeat as bears within it the germ of future victory.

Is her reading correct? Time will prove. Meanwhile she will have confidence in herself, and that this confidence might be well founded she decided to spend the rest of the night in formulating her plans and laying out her imaginary campaign.

Leaving the dresser she recommenced that rapid walking to and fro which was working such havoc in the nerves of the man in the room below her. When she paused, it was to ransack a trunk and bring out a flat wallet filled with newspaper clippings, many of them discoloured by time, and all of them showing marks of frequent handling.

A handling now to be repeated. For after a few moments spent in arranging them, she deliberately set about their complete reperusal, a task in which it has now become necessary for us to join her.

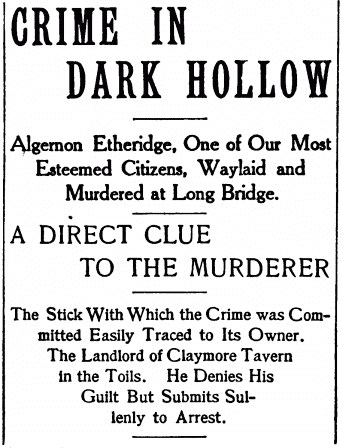

The first was black with old head-lines:

Particulars followed.

"Last evening Shelby's clean record was blackened by outrageous crime. Some time after nightfall a carter was driving home by Factory Road, when just as he was nearing Long Bridge one of his horses shied so violently that he barely escaped being thrown from his seat. As he had never known the animal to shy like this before, he was curious enough to get down and look about him for the cause. Dark Hollow is never light, but it is impenetrable after dark, and not being able to see anything, he knelt down in the road and began to feel about with his hand. This brought results. In a few moments he came upon the body of a man lying without movement, and seemingly without life.

"Long Bridge is not a favourite spot at night, and, knowing that in all probability an hour might elapse before assistance would arrive in the shape of another passer-by, he decided to carry his story straight to Claymore Tavern. Afterwards he was heard to declare that it was fortunate his horses were headed that way instead of the other, or he might have missed seeing the skulking figure which slipped down into the ravine as he made the turn at the far end of the bridge—a figure which had no other response to his loud 'Hola!' than a short cough, hurriedly choked back. He could not see the face or identify the figure, but he knew the cough. He had heard it a hundred times; and, saying to himself, 'I'll find fellers enough at the tavern, but there's one I won't find there and that's John Scoville,' he whipped his horse up the hill and took the road to Claymore.

"And he was right. A dozen fellows started up at his call, but Scoville was not among them. He had been out for two hours; which the carter having heard, he looked down, but said nothing except 'Come along, boys! I'll drive you to the turn of the bridge.'

"But just as they were starting Scoville appeared. He was hatless and dishevelled and reeled heavily with liquor. He also tried to smile, which made the carter lean quickly down and with very little ceremony drag him up into the cart. So with Scoville amongst them they rode quickly back to the bridge, the landlord coughing, the men all grimly silent.

"In crossing the bridge he made more than one effort to escape, but the men were determined, and when they finally stooped over the man lying in Dark Hollow, he was in their midst and was forced to stoop also.

"One flash of the lantern told the dismal tale. The man was not only dead, but murdered. His forehead had been battered in with a knotted stick; all his pockets hung out empty; and from the general disorder of his dress it was evident that his watch had been torn away by a ruthless hand. But the face they failed to recognise till some people, running down from the upper town where the alarm had by this time spread, sent up the shout of 'It's Mr. Etheridge! Judge Ostrander's great friend. Let some one run and notify the judge.'