полная версия

полная версияBlackwood's Edinburgh Magazine - Volume 61, No. 376, February, 1847

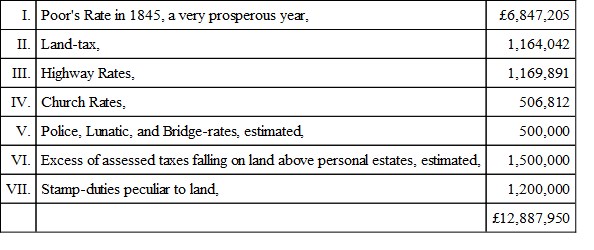

Persons not practically acquainted with these matters may think this statement is overcharged: on the contrary, it is within the truth in some instances. We know an instance of a great iron master, whose profits average above £100,000 a-year, who pays less poor's rates for the poor he has mainly created, than a landholder in the same parish, of £2000 a-year, who never brought a pauper on its funds in his life. Such is the consequences of the present barbarous system of levying the poor's rate as an income tax on the landlords who are burdened with paupers, and only a house tax on the manufacturers who create and profit by them. The first thing to be done towards the introduction of a just system of direct taxation is to lay the maintenance of the poor equally on all classes; and above all to abolish the present most unjust system of making it only a house tax on the producers of poor in towns, and an income tax on their feeders in the country.

The Land Tax is another burden, exclusively affecting real property, which should either be abolished, altogether or levied equally on all classes. Its amount is not so great as the poor's rate, nevertheless it is considerable, as it produces about £1,172,000 a-year.22

The whole Assessed Taxes, though not avowedly and exclusively a tax on the landed interest, are, practically speaking, and in reality, a burden on them almost entirely; at least they are so much heavier on the landowners than the inhabitants of towns, that the burden is nothing in comparison on urban indwellers. Had they been practically felt as a grievance by the urban population they would long since have shared the fate of the house tax and been abolished. They have so long been kept up only because, with a few exceptions, they press almost exclusively upon that passive and supine class of landlords, the natural prey of Chancellors of the Exchequer, whom it seems generally impossible by any exertions, or the advent of any danger how urgent soever, to rouse to any common measure of defence. It no doubt sounds well to say that the assessed taxes are laid generally on luxuries, and therefore they are paid equally by all classes which indulge in them. But a closer examination will show that this view is entirely fallacious, and that the subjects actually taxed, though really luxuries to urban, are necessary aids to rural life. For example, a carriage, a riding horse, a coachman, a groom, are really luxuries in town, and their use may be considered as a fair test of affluent, or at least easy circumstances. But in the country they are absolutely necessaries. They are indispensable to business, to health, to mutual communication, to society, to existence. What similarity is there between the situation of a merchant with £1000 a-year, living in a comfortable town house, with an omnibus driving past his door every five minutes, a stand of cabs within call, and dining three days in the week at a club where he needs no servants of his own; and a landholder enjoying the same income, living in a country situation, with no neighbour within five miles, and having six miles to ride or drive to the nearest town or railway station where his business is to be transacted, or where a public conveyance can be reached?

Gardeners, park-keepers, foresters and the like, are generally not luxuries in the country, they are a necessary part of an establishment which is to turn the land to a profitable use. You might as well tax operatives in mills, or miners in collieries, or mechanics in manufactories, as such servants. Yet they are all swept into the assessed taxes, upon the rude and unfounded presumption that they are, equally with a large establishment of men-servants in towns, an indication of affluent circumstances. The window tax is incomparably, more oppressive in country houses than in town ones, from their greater size in general, and being for the most part constructed at a period when no attention was paid to the number of windows, and they were generally made very small from being formed before the window tax was laid on. Taking all these circumstances into view, it is not going too far to assert, that on equal fortunes the assessed taxes are twice as heavy in the country as in towns; and that of £3,312,000 which they produce annually, after deducting the land tax, about £2,500,000, is paid by landowners either in town or country. It is inconceivable—no one a priori could credit it—how few householders in town, and not being landowners, pay any assessed taxes at all—or any of such amount as to be really a burden. The total number of houses charged to the window tax, in Great Britain, is 447,000, and the duty levied on them is, £1,613,774, or, at an average, about £3, 10s. a-house, while the number of inhabited houses was, in 1841, 3,164,000, or above seven times the number. The total number charged with one man-servant, is only 49,320, and, persons keeping men-servants at all, 110,849,23 facts indicating how extremely partial is the operation of these taxes, and how severely they fall on the class most heavily burdened in other respects, and therefore least able to bear them.

The Highway Rates are another burden exclusively affecting land, although the whole community derive benefit from their use. This burden, exclusive of the sum levied at turnpike gates, in England amounted to £1,169,891, a-year.24 This charge, heavy as it is, is felt as the more vexatious, that the rate-payers are not at liberty either to limit the use of the road, for which they pay, to themselves, or to allow it to fall into disrepair. An indictment of the road lies at common law, if it becomes unfit for traffic, even at the instance of any party using the road, though he does not pay any part of the rate. In other words, the neighbouring landholders are compelled to keep up the roads for the benefit of the public generally, who contribute nothing towards their maintenance. This matter becomes the more serious that in consequence of the general adoption and immense spread of railways, the traffic on the principal lines of road in England, has either almost entirely disappeared, or become inadequate to contributing any thing material to the support even of the turnpikes hitherto entirely maintained by them. It is not difficult to foresee, that the time is not far distant when nearly the whole roads of England will fall as a burden on the rate payers; for these roads cannot be abandoned, or the country off the railway lines would have no communication at all. And the sums paid by railway companies, how large soever, to landholders, afford no general compensation; for they benefit a few in the close vicinity of the railways only, while the highway rate affects all.

The Church Rate is another burden exclusively affecting land, though all classes obtain the benefit of it in the comfort and convenience of churches. It amounted, in 1839, the last year for which a return was made, to £506,512.25 Nothing can be clearer than that this is a burden truly affecting real estates. It is entirely different from tithes, which are not, correctly speaking, a burden on land, but a separate estate apart from that of the landlord, which never was his, for which he has given no valuable consideration. But on what principle of justice is the burden of upholding churches exclusively laid on the land, when all classes sit in churches, and enjoy the benefit of their accommodation. The thing is evidently and palpably unjust, and won't bear an argument.

The Police, Lunatic Asylum, and Bridge Rates, constitute another burden on real property to which no other property is subject, which, though not universally introduced, are very oppressive in those counties where their establishment has been found necessary. Mr. Blamire, a very competent witness, estimates these incidental and partial charges at 2s. 1d. an acre.26 The land is still liable also to a heavy disbursement on account of the Militia, if that national force should be again called out. There has been no return yet laid before parliament of these partial burdens on land, but they cannot be estimated at less than the church rate, or £500,000 a-year.

The Stamp Duties, from deeds and instruments which produce annually £1,646,000 a-year, fall for the most part as a burden on real property. This must be evident to every person who considers that real estates in land or houses are the great security on which money is advanced in every part of the country, and the extremely heavy burdens, in the shape of a direct payment in the requisite stamps for deeds to government, is imposed on the transmission and burdening of such property. It is particularly severe, in proportion to the value of the subjects burdened, in the mortgaging or alienating of small freeholds or heritable subjects. It is stated in the Lords' Report, on the burdens affecting real property, "The stamp on a conveyance of a certain length, on a sale of real subjects of the value of £50, would cost 12-1/2 per cent, or £6, 10s.; on a £100 sale, to 5 per cent; on a £200 sale, to 2-1/2 per cent; on a £500 sale, to £1, 14s. 3d. per £100; and above that sum, to one per cent." The weight on the establishment of mortgages, especially on small sums, is not less remarkable. The same report adds, "A mortgage for £50 costs, in stamps, and law expenses, thirty per cent.; a mortgage for £100, twenty per cent.; one for £450 seven per cent.; for £1500 three per cent.; for £12,500 one per cent.; for £25,000 fifteen shillings per cent, and for £100,000 twelve shillings per cent."27 These burdens on the sale or mortgaging of real property are felt as the more oppressive, when it is recollected that movable property to the greatest amount, as in the public funds, or the like, may be alienated, or burdened in the most valid and effectual manner for the cost of a power of attorney, which is a guinea and half-a-crown per cent. to the broker who executes the transaction. Materials do not exist for separating exactly the deed-stamps falling as a burden on land transmissions and mortgages, from those affecting personal estates; but it is certainly within the mark to say, that they are three-fourths of the whole stamp-duties on deeds and instruments, or £1,200,000 a-year.

Thus, it appears that, setting aside the tithe, as not the land-owner's property, and, therefore, a separate estate, and not, properly speaking, a burden on land; and saying nothing of the malt-tax, which produces annually £4,500,000 a-year, on the supposition that, at present at least, that falls as a burden on the consumer; and saying nothing of the income-tax, which, as will immediately appear, falls as a much severer burden on land-rents than commercial incomes,—these distinct, clear, and indisputable burdens laid on land, from which property of other sorts in England are exempt, stand thus:—

The rental of real property in England, rated to the Poor's Rates, is £62,540,030;28 but the real rental, as ascertained by the more rigid and accurate returns for the Income-tax, is £85,802,735. On the first of these sums, the taxes exclusively falling on land amount to a tax of twenty-five, on the last of eighteen per cent. annually. This is in addition to the Income-tax, and all the indirect taxes which the owners of land and houses pay in common with all the rest of the community, and which by it are complained of as so oppressive.

Enough, it is thought, has now been said to prove the extreme inequality and injustice with which direct public burdens are levied in this country, and the necessity for a thorough and searching revision of our system of taxation, in this respect, especially since, from the way in which the tide sets, it has become so evident that direct will progressively be more extensively substituted for indirect taxation. But, in addition to these, there are several other circumstances which aggravate fourfold the burdens thus exclusively laid on real property.

I. In the first place, the alterations in the monetary system of the country, by the resumption of cash payments in 1819, followed up in Scotland and Ireland, as well as England, by the stringent Bankers' Act of 1844, has added fully forty per cent. to the weight of all taxes and other burdens, public or private, affecting landed property, because it has altered, to that extent, the value of money, and diminished the price of the articles of rural produce from which the laud-holders' means of paying them are derived. If the prices of wheat and of all other kinds of agricultural produce, for ten years before 1819, and ten years before 1845, be compared, it will at once appear that the difference is even greater than has been here stated.29 But that consideration is of vital importance in this question, for if the price of all kinds of rural produce has declined nearly as nine to six by the operation of these monetary changes, the weight of debts and taxes, of course, must have been increased in the same proportion. We are not now to enter into any argument as to the expedience or necessity of that great change in our monetary system: we assume it as a fact, and refer to it only as rendering imperative a revision of the direct taxes bearing so heavily on the great interests whose means of paying them have been thus so seriously abridged.

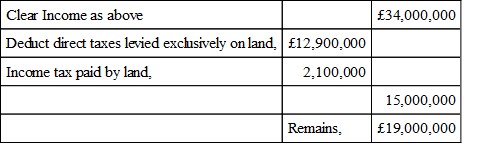

II. In the second place, and this is a most important circumstance, the burdens which have been mentioned all fall as a burden on the landowner, how much soever his property may be charged with mortgages, jointures, or other real burdens. These must all be paid in full by himself alone, how small soever be the fraction of the nominal income of his estate which remains to him after discharging the annual amount of its real burdens. There is no right to deduct poor's rates, land tax, or other burdens affecting land, from mortgages, or even jointure holders, unless they are expressly declared liable to such, which is very seldom the case. These annual charges must all be paid clear to the creditor, without any deduction, except that of the income tax, which the debtor is allowed to retain by the Act imposing it. But this consideration is of vital importance to the landholders when the amount of their mortgages and other real burdens is taken into consideration. Their annual amount has been estimated by very competent judges at two-thirds of the income derived from land, although, as there is no general record in England for real burdens, their amount cannot at present be accurately ascertained. But take it, in order to be within the mark, at three-fifths of the real rental, as ascertained by the income tax returns, these show, as already stated, an income of £85,000,000 annually derived from land. Take three-fifths, or £51,000,000 of this sum as absorbed annually by mortgagers and annuitants holding real and preferable securities over land, and there will remain £34,000,000 annually to the holders of land and houses. Now on this £34,000,000 the real burdens above mentioned, amounting to £12,900,000 a-year, are fastened. If to these be added the income tax paid by the land, amounting, by the income tax returns, to £2,112,000, the clear income derived by landholders from the real property of England, with the direct taxes paid by them, will stand thus—

Thus it appears that out of thirty-four millions of clear rental left to the owners of real property in England, no less than fifteen millions, or nearly a half, is taken from them annually in the shape of direct taxes which they cannot by any possibility avoid! How long would the commercial or city industry of England stand direct taxes to the amount of 46 per cent on their clear income? If that had been the state of their finances, we should have had no clamour in 1831 for enlarged representation, or in 1846 for the destruction, to their advantage, of all the protection to other branches of industry. We should have had no Anti-Corn Law League subscriptions of £100,000 to buy up all the venal talent in the form of itinerant orators and pamphleteers in the country. We should have had no conversions of conceding premiers by the weight of external agitation. In social, not less than military warfare, the longest purse carries the day; and the party which is the heaviest burdened is sure to be in the end overthrown.

III. The abolition of the Corn Laws, partially at present, entirely at the end of two years and a half, by the bill of 1846, not only has made this enormous burden of 46 per cent. on their clear income deductis debitis a permanent load on the landowners, but it has rendered it a hopeless one, because it has destroyed every means which they previously might have possessed of indemnifying themselves for its weight, by sharing its oppression with other classes. This is a matter of the very highest importance, which will soon make itself felt, though, in consequence of the nearly total failure of the potato crop in the west of Great Britain and Ireland, it has not yet been so. The usual resource of persons, who are burdened with heavy payments to government, is to lay as much as they can of it on others, by enhancing as much as possible the price of their produce. It is in this way that indirect taxes fall in general on the consumer; and it is on this principle that, in estimating the burdens exclusively affecting land, we have not included the malt duty, because it is in great part at least paid by the consumers of beer or porter. But, of course, if it becomes from any cause impossible for the party burdened, in the first instance, to raise the price of his produce, or if, on the contrary, he is compelled to lower it, the whole tax will fall direct on himself, because he will be without the means of laying it on the purchaser from him.

Now, the abolition of the Corn Laws has done this. In two years and a half, the whole grain of Poland and America will be admitted into the English market at the nominal duty of a shilling a quarter. It will be impossible for the farmers and landowners after that to keep up the price of grain of any sort in the British market beyond the prices in Prussia, and with the addition of 5s. a quarter for the cost of transit, and perhaps half as much for the profit of the importer. Wheat, beyond all question, will fall on an average of years to forty shillings a quarter, barley and oats to twenty. This is just as certain as the parallel reduction of average prices of wheat from 87s. a quarter to 56s. has been by the money law of 1819. Accordingly, now that the stress is over, they have no longer an interest to conceal or pervert the truth; the anti-corn law journals are the first to proclaim this result as certain, and they coolly recommend the English farmers to abandon altogether the cultivation of wheat, which can no longer be expected to pay, and to lay out their lands in pasture grass and the producing of garden stuffs. But amidst this general and now admitted decline in the price of grain, the 46 per cent. of direct burdens on land will continue unchanged; happy if it does not receive a large augmentation. The effect of this will be to augment the weight of the burdens to which they are already subjected on the landholders by at least twenty per cent., and, in addition, to throw upon them the whole malt tax, now amounting to £4,500,000 a-year. The moment the British farmer is obliged to lower the price of his barley to the level of the continental nations, where labour is so much cheaper, and rents comparatively light, the whole malt tax falls, without deduction or limitation, on British agriculture.

IV. The income tax, though apparently a burden equally affecting all classes, in reality attaches with much more severity to the landed than to any other class. There is, indeed, an advantage unduly enjoyed by capitalists of all sorts, landed or moneyed, in comparison with annuitants or professional men, which, as will immediately appear, loudly calls for a remedy. But, as compared with the merchant or moneyed man, who derives his income from trade or realised capital in a movable form, the landholder is, in every direct taxation, exposed to a most serious disadvantage. His income cannot be concealed, and it is returned by others than himself. The farmer or tenant, who has no interest in the matter, returns his landlord's rent. The trader, shopkeeper, or merchant estimates and returns his own income. The possessions of the first, and their annual rental, are universally known, and concealment as to them is impossible or sure of detection; the gains of the last are entirely secret, and wrapped up, even to the owner, in books or accounts, generally unintelligible in all cases but those of considerable merchants—to all but the persons who prepared them. Whoever is practically acquainted with human nature will at once perceive the immense effect which this difference must have on the amount of the burden, in appearance the same, as it affects the different classes of society.

And the result of this difference appears in the most decisive manner, in the amount of the sums paid by the different classes of society, as shown by the income tax returns. From them, it appears that the contributions from commerce, trades, and professions of all sorts, is not quite half of that obtained from landed property. The first is, in round numbers, £2,700,000; the second, £1,500,000.30 But let it be recollected that the £1,541,000 a-year, which, in 1845, was paid by professional men of all descriptions, in Great Britain, included, besides merchants and traders, the whole class of professional men not traders, as lawyers, attorneys, physicians, &c. At the very lowest computation their share of this must amount to £341,000 a-year. There remains then £1,200,000 as the contribution of trade and commerce, of all kinds, from Great Britain, while that from land is £2,670,000 a-year, or considerably more than double. Can it be believed that this is founded on a fair return of incomes by the commercial classes? Are they prepared to admit that their property and income, and consequent interest and title to sway in the state, is not half of that which is derived from land? Or do they shelter themselves under the comfortable assurance that their real income is incomparably greater, and that they quietly escape with a half or a third of the income tax which they ought to pay? We leave it to the trading class, and their abettors in the press, to settle this question with the commissioners of income tax throughout the country. We mention the fact, that trade and commerce do not pay half the income tax that land does, as a reason, among the many others which exist, for a thorough and radical reform of our financial system, so far as direct taxation is concerned.

Whoever considers seriously, and in an impartial spirit, the various particulars which have now been stated, will not only cease to wonder at the frequent, it may almost be said universal, embarrassment of the landed proprietors, but he will arrive at the conclusion, that if they continue much longer unchanged, they must terminate in their general ruin. We say general ruin, because it will not be universal. The great landowners, the magnates, whether moneyed or territorial, of the land will alone survive the general wreck. They will, by degrees, swallow up all the smaller estates in their neighbourhood; and it will come to be literally true in Britain what was said, by a Roman emperor, of Gaul, in the decline of the empire, "That the estates of the rich go on continually increasing and absorbing all lesser estates around them, till they come to the estate of another as rich as themselves." With direct taxes, amounting to 50 or 60 per cent. on the disposable income, which, under the change of prices, induced by the change in the corn laws, they will very soon be, even without any addition from farther taxes, it is wholly impossible that any landowner who does not possess enormous tracts of country, or vast funded or moneyed property in addition to his territorial possessions, can avoid insolvency. What the effect of the total destruction of the middle class of British landholders must be on the balance of the constitution, and the state of society in these islands, it is not our present purpose to inquire. Suffice it to say, that it is precisely the state of things which signalised the later stages of the Roman empire, and coincides with so many other circumstances in marking the striking analogy between our present condition and that which proved fatal to the ancient masters of the world.