полная версия

полная версияDiary in America, Series One

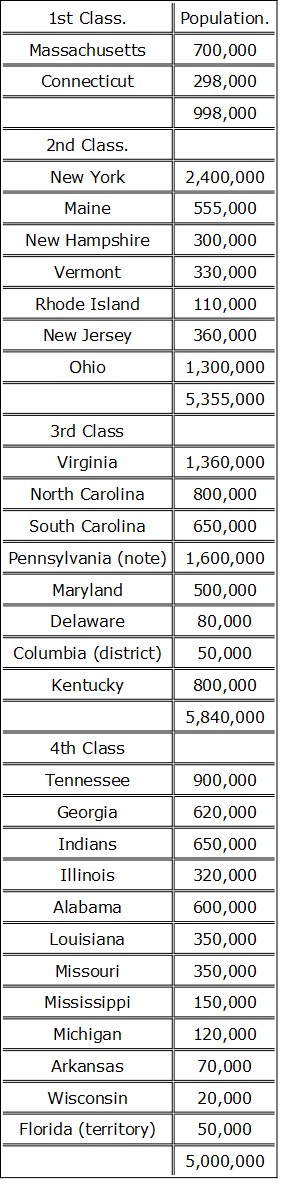

I readily assent to this, and I consider Connecticut equal to Massachusetts; but as you leave these two states, you find that education gradually diminishes. New York is the next in rank, and thus the scale descends until you arrive at absolute ignorance.

I will now give what I consider as a fair and impartial tabular analysis of the degrees of education in the different states in the Union. It may be cavilled at, but it will nevertheless be a fair approximation. It must be remembered that it is not intended to imply that there are not a certain portion of well-educated people in those states put down in class 4, as ignorant states, but they are included in the Northern states, where they principally receive their education.

Degrees of Education in the different States in the Union.

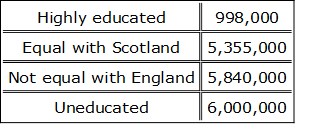

If I am correct, it appears then that we have:—

This census is an estimate of 1836, sufficiently near for the purpose. It is supposed that the population of the united States has since increased about two millions, and of that increase the great majority is in the Western states, where the people are wholly uneducated. Taking, therefore, the first three classes, in which there is education in various degrees, we find that they amount to 12,193,000; against which we may fairly put the 5,000,000 uneducated, adding to it, the 2,000,000 increased population, and 3,000,000 of slaves.

I believe the above to be a fair estimate, although nothing positive can be collected from it. In making a comparison of the degree of education in the United States and in England, one point should not be overlooked. In England, children may be sent to school, but they are taken away as soon as they are useful, and have little time to follow up their education afterwards. Worked like machines, every hour is devoted to labour, and a large portion forget, from disuse, what they have learnt when young. In America, they have the advantage not only of being educated, but of having plenty of time, if they choose, to profit by their education in after life. The mass in America ought, therefore, to be better educated than the mass in England, where circumstances are against it. I must now examine the nature of education given in the United States.

It is admitted as an axiom in the United States, that the only chance they have of upholding their present institutions is by the education of the mass; that is to say, a people who would govern themselves must be enlightened. Convinced of this necessity, every pains has been taken by the Federal and State governments to provide the necessary means of education. This is granted; but we now have to inquire into the nature of the education, and the advantages derived from such education as is received in the United States.

In the first place, what is education? Is teaching a boy to read and write education? If so, a large proportion of the American community may be said to be educated; but, if you supply a man with a chest of tools, does he therefore become a carpenter! You certainly give him the means of working at the trade, but instead of learning it, he may only cut his fingers. Reading and writing without the farther assistance necessary to guide people aright, is nothing more than a chest of tools.

Then, what is education? I consider that education commences before a child can walk: the first principle of education, the most important, and without which all subsequent are but as leather and prunella, is the lesson of obedience—of submitting to parental control—“Honour thy father and thy mother!”

Now, any one who has been in the United States must have perceived that there is little or no parental control. This has been remarked by most of the writers who have visited the country; indeed to an Englishman it is a most remarkable feature. How is it possible for a child to be brought up in the way that it should go, when he is not obedient to the will of his parents? I have often fallen into a melancholy sort of musing after witnessing such remarkable specimens of uncontrolled will in children; and as the father and mother both smiled at it, I have thought that they little knew what sorrow and vexation were probably in store for them, in consequence of their own injudicious treatment of their offspring. Imagine a child of three years old in England behaving thus:—

“Johnny, my dear, come here,” says his mamma.

“I won’t,” cries Johnny.

“You must, my love, you are all wet, and you’ll catch cold.”

“I won’t,” replies Johnny.

“Come, my sweet, and I’ve something for you.”

“I won’t.”

“Oh! Mr —, do, pray make Johnny come in.”

“Come in, Johnny,” says the father.

“I won’t.”

“I tell you, come in directly, sir—do you hear?”

“I won’t,” replies the urchin taking to his heels.

“A sturdy republican, sir,” says his father to me, smiling at the boy’s resolute disobedience.

Be it recollected that I give this as one instance of a thousand which I witnessed during my sojourn in the country.

It may be inquired, how is it that such is the case at present, when the obedience to parents was so rigorously inculcated by the puritan fathers, that by the blue laws, the punishment of disobedience was death? Captain Hall ascribes it to the democracy, and the rights of equality therein acknowledged; but I think, allowing the spirit of their institutions to have some effect in producing this evil, that the principal cause of it is the total neglect of the children by the father, and his absence in his professional pursuits, and the natural weakness of most mothers, when their children are left altogether to their care and guidance.

Mr Sanderson, in his Sketches of Paris, observes:– “The motherly virtues of our women, so eulogised by foreigners, is not entitled to unqualified praise. There is no country in which maternal care is so assiduous; but also there is none in which examples of injudicious tenderness are so frequent.” This I believe to be true; not that the American women are really more injudicious than those of England, but because they are not supported as they should be by the authority of the father, of whom the child should always entertain a certain portion of fear mixed with affection, to counterbalance the indulgence accorded by natural yearnings of a mother’s heart.

The self-will arising from this fundamental error manifests itself throughout the whole career of the American’s existence, and, consequently, it is a self-willed nation par excellence.

At the age of six or seven you will hear both boys and girls contradicting their fathers and mothers, and advancing their own opinions with a firmness which is very striking.

At fourteen or fifteen the boys will seldom remain longer at school. At college, it is the same thing; (note 6) and they learn precisely what they please, and no more. Corporal punishment is not permitted; indeed, if we are to judge from an extract I took from an American paper, the case is reversed.

The following “Rules” are posted up in New Jersey school-house:—

“No kissing girls in school-time; no licking the master during holy days.”

At fifteen or sixteen, if not at college, the boy assumes the man; he enters into business, as a clerk to some merchant, or in some store. His father’s home is abandoned, except when it may suit his convenience, his salary being sufficient for most of his wants. He frequents the bar, calls for gin cocktails, chews tobacco, and talks politics. His theoretical education, whether he has profited much by it or not, is now superseded by a more practical one, in which he obtains a most rapid proficiency. I have no hesitation in asserting that there is more practical knowledge among the Americans than among any other people under the sun. (note 7).

It is singular that in America, everything, whether it be of good of evil, appears to assist the country in going a-head. This very want of parental control, however it may affect the morals of the community, is certainly advantageous to America, as far as her rapid advancement is concerned. Boys are working like men for years before they would be in England; time is money, and they assist to bring in the harvest.

But does this independence on the part of the youth of America end here? On the contrary, what at first was independence, assumes next the form of opposition, and eventually that of control.

The young men before they are qualified by age to claim their rights as citizens, have their societies, their book-clubs, their political meetings, their resolutions, all of which are promulgated in the newspapers; and very often the young men’s societies are called upon by the newspapers to come forward with their opinions. Here is opposition. Mr Cooper says, on page 152 of his “Democrat”:—

“The defects in American deportment are, notwithstanding, numerous and palpable. Among the first may be ranked, insubordination in children, and a great want of respect for age. The former vice may be ascribed to the business habits of the country, which leave so little time for parental instruction, and, perhaps, in some degree to the acts of political agents, who, with their own advantages in view, among the other expedients of their cunning, have resorted to the artifice of separating children from their natural advisers by calling meetings of the young to decide on the fortunes and policy of the country.”

But what is more remarkable, is the fact that society has been usurped by the young people, and the married and old people have been, to a certain degree, excluded from it. A young lady will give a ball, and ask none but young men and young women of her acquaintance; not a chaperon is permitted to enter, and her father and mother are requested to stay upstairs, that they may not interfere with the amusement. This is constantly the case in Philadelphia and Baltimore, and I have heard bitter complaints made by the married people concerning it. Here is control. Mr Sanderson, in his “Sketches of Paris,” observes:—

“They who give a tone to society should have maturity of mind; they should have refinement of taste, which is a quality of age. As long as college beaux and boarding-school misses take the lead, it must be an insipid society, in whatever community it may exist. Is it not villainous in your Quakerships of Philadelphia, to lay us, before we have lived half our time out, upon the shelf! Some of the native tribes, more merciful, eat the old folks out of the way.”

However, retribution follows: in their turn they marry, and are ejected; they have children, and are disobeyed. The pangs which they have occasioned to their own parents are now suffered by them in return, through the conduct of their own children; and thus it goes on, and will go on, until the system is changed.

All this is undeniable; and thus it appears that the youth of America, being under no control, acquire just as much as they please, and no more, of what may be termed theoretical knowledge. Thus is the first great error in American education, for how many boys are there who will learn without coercion, in proportion to the number who will not? Certainly not one in ten, and, therefore it may be assumed that not one in ten is properly instructed. (See note 6.)

Now, that the education of the youth of America is much injured by the want of control on the part of the parents, is easily established by the fact that in those states where the parental control is the greatest, as in Massachusetts, the education is proportionably superior. But this great error is followed by consequences even more lamentable: it is the first dissolving power of the kindred attraction, so manifest throughout all American society. Beyond the period of infancy there is no endearment between the parents and children; none of that sweet spirit of affection between brother and sisters; none of those links which unite one family; of that mutual confidence; that rejoicing in each other’s success; that refuge, when they are depressed or afflicted, in the bosoms of those who love us—the sweetest portion of human existence, which supports us wider, and encourages us firmly to brave, the ills of life—nothing of this exists. In short, there is hardly such a thing in America as “Home, sweet home.” That there are exceptions to this, I grant but I speak of the great majority of cases, and the results upon the character of the nation. Mr Cooper, speaking of the weakness of the family tie in America, says—

“Let the reason be what it will, the effect is to cut us off from a large portion of the happiness that is dependent on the affections.”

The next error of American education is, that in their anxiety to instil into the minds of youth a proper and ardent love of their own institutions, feelings and sentiments are fostered which ought to be most carefully checked. It matters little whether these feelings (in themselves vices) are directed against the institutions of other countries; the vice once engendered remains, and hatred once implanted in the breast of youth, will not be confined in its action. Neither will national conceit remain only national conceit, or vanity be confined to admiration of a form of government; in the present mode of educating the youth of America, all sight is lost of humility, good-will, and the other Christian virtues, which are necessary to constitute a good man, whether he be an American, or of any other country.

Let us examine the manner in which a child is taught. Democracy, equality, the vastness of his own country, the glorious independence, the superiority, of the Americans in all conflicts by sea or land, are impressed upon his mind before he can well read. All their elementary books contain garbled and false accounts of naval and land engagements, in which every credit is given to the Americans, and equal vituperation and disgrace thrown upon their opponents. Monarchy is derided, the equal rights of man declared—all is invective, uncharitableness, and falsehood.

That I may not in this be supposed to have asserted too much, I will quote a reading-lesson from a child’s book, which I purchased in America as a curiosity, and is now in my possession. It is called the “Primary Reader for Young Children,” and contains many stories besides this, relative to the history of the country.

“Lesson” 62“Story about the 4th of July”6. “I must tell you what the people of New York did. In a certain spot in that city there stood a large statue, or representation of King George III. It was made of lead. In one hand he held a sceptre, or kind of sword, and on his head he wore a crown.”

7. “When the news of the Declaration of Independence reached the city, a great multitude were seen running to the statue.”

8. “The cry was heard, ‘Down with it—down with it!’ and soon a rope was placed about its neck, and the leaden King George came tumbling down.”

9. “This might fairly be interpreted as a striking prediction of the downfall of the monarchical form of government in these United States.”

10. “If we look into history, we shall frequently find great events proceeding from as trifling causes as the fall of the leaden statue, which not unaptly represents the character of a despotic prince.”

11. “I shall only add, that when the statue was fairly down, it was cut to pieces, and converted into musket-balls to kill the soldiers whom his majesty had sent over to fight the Americans.”

This is quite sufficient for a specimen. I have no doubt that it will be argued by the Americans—“We are justified in bringing up our youth to love our institutions.” I admit it; but you bring them up to hate other people, before they have sufficient intellect to understand the merits of the case.

The author of “A Voice from America,” observes:—

“Such, to a great extent is the unavoidable effect of that political education which is indispensable to all classes of a self-governed people. They must be trained to it from their cradle; it must go into all schools; it must thoroughly leaven the national literature, it must be ‘line upon line, and precept upon precept,’ here a little and there a little; it must be sung, discoursed, and thought upon everywhere and by every body.”

And so it is; and as if this scholastic drilling were not sufficient, every year brings round the 4th of July, on which is read in every portion of the states the act of independence, in itself sufficiently vituperative, but invariably followed-up by one speech (if not more) from some great personage of the village, hamlet, town, or city, as it may be, in which the more violent he is against monarchy and the English, and the more he flatters his own countrymen, the more is his speech applauded.

Every year is this drilled into the ears of the American boy, until he leaves school, when he takes a political part himself, connecting himself with young men’s society, where he spouts about tyrants, crowned heads, shades of his forefathers, blood flowing like water, independence, and glory.

The Rev. Mr Reid very truly observes, of the reading of the Declaration of Independence:– “There is one thing, however, that may justly claim the calm consideration of a great and generous people. Now that half a century has passed away, is it necessary to the pleasures of this day to revive feelings in the children which, if they were found in the parent, were to be excused only by the extremities to which they were pressed? Is it generous, now that they have achieved the victory, not to forgive the adversary? Is it manly, now that they have nothing to fear from Britain, to indulge in expressions of hate amid vindictiveness, which are the proper language of fear? Would there be less patriotism, because there was more charity? America should feel that her destinies are high and peculiar. She should scorn the patriotism which cherishes the love of one’s own country, by the hatred of all others.”

I think, after what I have brought forward, the reader will agree with me, that the education of the youth in the United States is immoral, and the evidence that it is so, is in the demoralisation which has taken place in the United States since the era of the Declaration of Independence, and which fact is freely admitted by so many American writers:—

“Aetas parentum pejor avis tulitNos nequieres, mox daturos Progeniem vitiosiorem.” Horace, book iii, ode 6.I shall by and by shew some of the effects produced by this injudicious system of education; of which, if it is necessary to uphold their democratical institutions, I can only say, with Dr Franklin, that the Americans “pay much too dear for their whistle.”

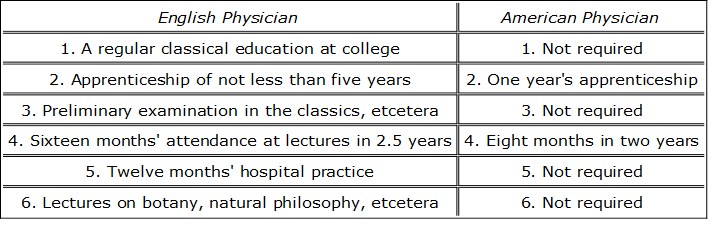

It is, however, a fact, that education (such as I have shown it to be) is in the United States more equally diffused. They have very few citizens of the States (except a portion of those in the West) who may be considered as “hewers of wood and drawers of water,” those duties being performed by the emigrant Irish and German, and the slave population. The education of the higher classes is not by any means equal to that of the old countries or Europe. You meet very rarely with a good classical scholar, or a very highly educated man, although some there certainly are, especially in the legal profession. The Americans have not the leisure for such attainments: hereafter they may have; but at present they do right to look principally to Europe for literature, as they can obtain it thence cheaper and better. In every liberal profession you will find that the ordeal necessary to be gone through is not such as it is with us; if it were, the difficulty of retaining the young men at college would be much increased. To show that such is the case, I will now just give the difference of the acquirements demanded in the new and old country to qualify a young man as an MD.

If the men in America enter so early into life that they have not time to obtain the acquirements supposed to be requisite with us, it is much the same thing with the females of the upper classes, who, from the precocious ripening by the climate and consequent early marriages, may be said to throw down their dolls that they may nurse their children.

The Americans are very justly proud of their women, and appear tacitly to acknowledge the want of theoretical education in their own sex, by the care and attention which they pay to the instruction of the other. Their exertions are, however, to a certain degree, checked by the circumstance, that there is not sufficient time allowed previous to the marriage of the females to give that solidity to their knowledge which would ensure its permanency. They attempt too much for so short a space of time. Two or three years are usually the period during which the young women remain at the establishments, or colleges I may call them (for in reality they are female colleges.) In the prospectus of the Albany Female Academy, I find that the classes run through the following branches:– French, book-keeping, ancient history, ecclesiastical history, history of literature, composition, political economy, American constitution, law, natural theology, mental philosophy, geometry, trigonometry, algebra, natural philosophy, astronomy, chemistry, botany, mineralogy, geology, natural history, and technology, besides drawing, penmanship, etcetera, etcetera.

It is almost impossible for the mind to retain, for any length of time, such a variety of knowledge, forced into it before a female has arrived to the age of sixteen or seventeen, at which age, the study of these sciences, as is the case in England, should commence not finish. I have already mentioned that the examinations which I attended were highly creditable both to preceptors and pupils; but the duties of an American woman as I shall hereafter explain, soon find her other occupation, and the ologies are lost in the realities of life. Diplomas are given at most of these establishments, on the young ladies completing their course of studies. Indeed, it appears to be almost necessary that a young lady should produce this diploma as a certificate of being qualified to bring up young republicans. I observed to an American gentlemen how youthful his wife appeared to be—“Yes,” replied he, “I married her a month after she had graduated.” The following are the terms of a diploma, which was given to a young lady at Cincinnati, and which she permitted me to copy:—

“In testimony of the zeal and industry with which Miss M— T— has prosecuted the prescribed course of studies in the Cincinnati Female Institution, and the honourable proficiency which she has attained in penmanship, arithmetic, English grammar, rhetoric, belles-lettres, composition, ancient and modern geography, ancient and modern history, chemistry, natural philosophy, astronomy, etcetera. etcetera. etcetera, of which she has given proofs by examination.

“And also as a mark of her amiable deportment, intellectual acquirements, and our affectionate regard, we have granted her this letter—the highest honour bestowed in this institution.”

(Seal.) “Given under our hands at Cincinnati, this 19th day of July, Anno Domini 1837.”

The ambition of the Americans to be a-head of other nations in every thing, produces, however, injurious effects, so far as the education of the women is concerned. The Americans will not “leave well alone,” they must “gild refined gold,” rather than not consider themselves in advance of other countries, particularly of England. They alter our language, and think that they have improved upon it; as in the same way they would raise the standard of morals higher than with us, and consequently fall much below us, appearances supplying the place of the reality. In these endeavours they sink into a sickly sentimentality, and, as I have observed before, attempts at refinement in language, really excite improper ideas. As a proof of the ridiculous excess to which this is occasionally carried, I shall insert an address which I observed in print; had such a document appeared in the English newspapers, it would have been considered as a hoax.