Полная версия

The Ships of Merior

JANNY WURTS

The Ships of Merior

The Wars Of Light And Shadows: Volume 2

HarperVoyager An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 1994

Copyright © Janny Wurts 1994

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780586210703

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2010 ISBN: 9780007346936

Version: 2018-12-04

Dedication

To my husband,

Don Maitz,

with all my love;

for understanding of desperate, long deadlines

above and beyond the call of duty.

This one’s for you.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

I. MISCREANT

II. VAGRANT

III. FIRST INFAMY

IV. CONVOCATION

V. MASQUE

VI. CRUX

VII SHIP’S PORT

VIII. RENEWAL

IX. SECOND INFAMY

X. MERIOR BY THE SEA

XI. DISCLOSURE

XII. ELAIRA

XIII. WAR HOST

XIV. VALLEYGAP TO WERPOINT

Keep Reading

Glossary

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by the Author

About the Publisher

I. MISCREANT

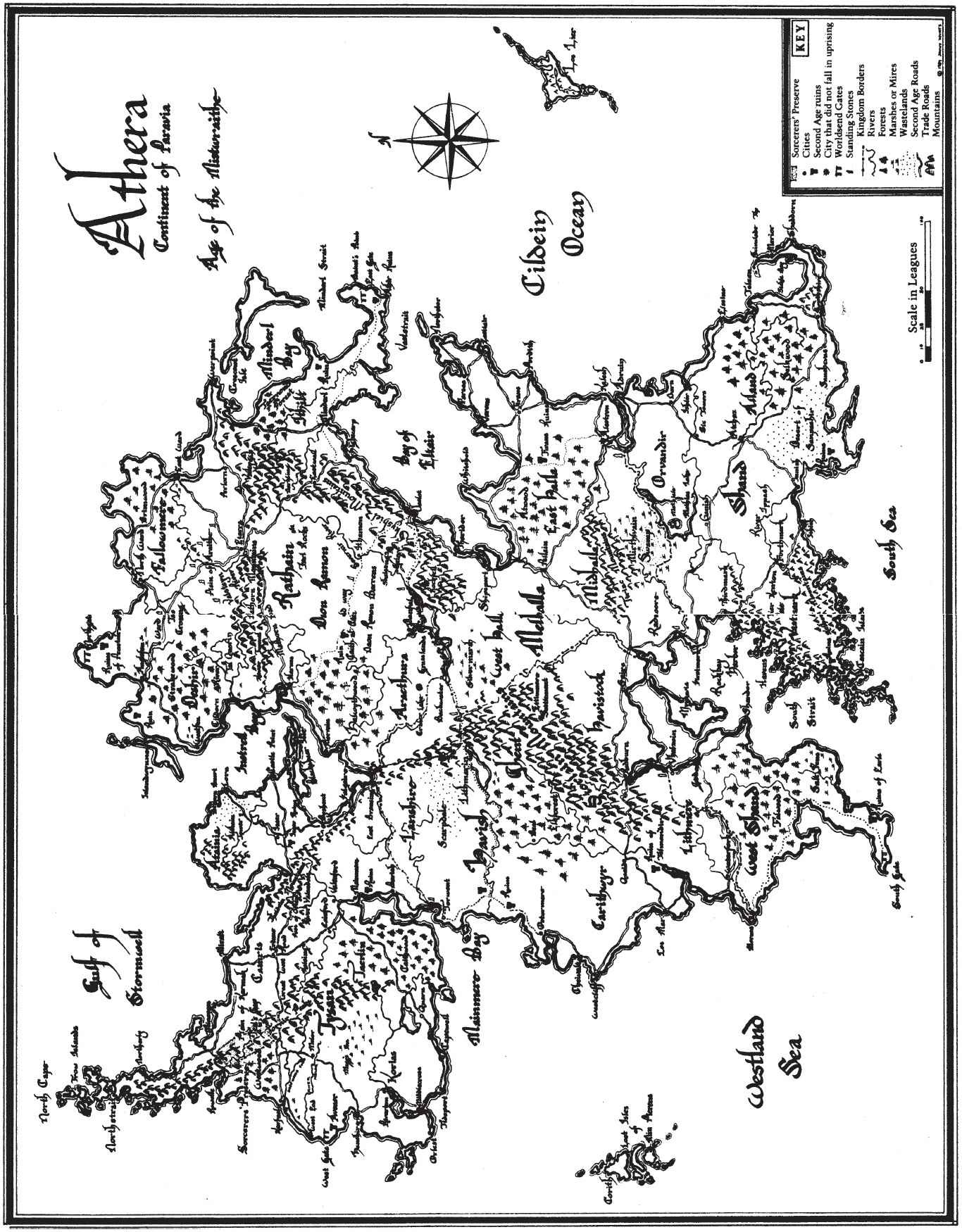

On the morning the Fellowship sorcerer who had crowned the King at Ostermere fared northward on the old disused road, the five years of peace precariously reestablished since the carnage that followed the Mistwraith’s defeat as yet showed no sign of breaking.

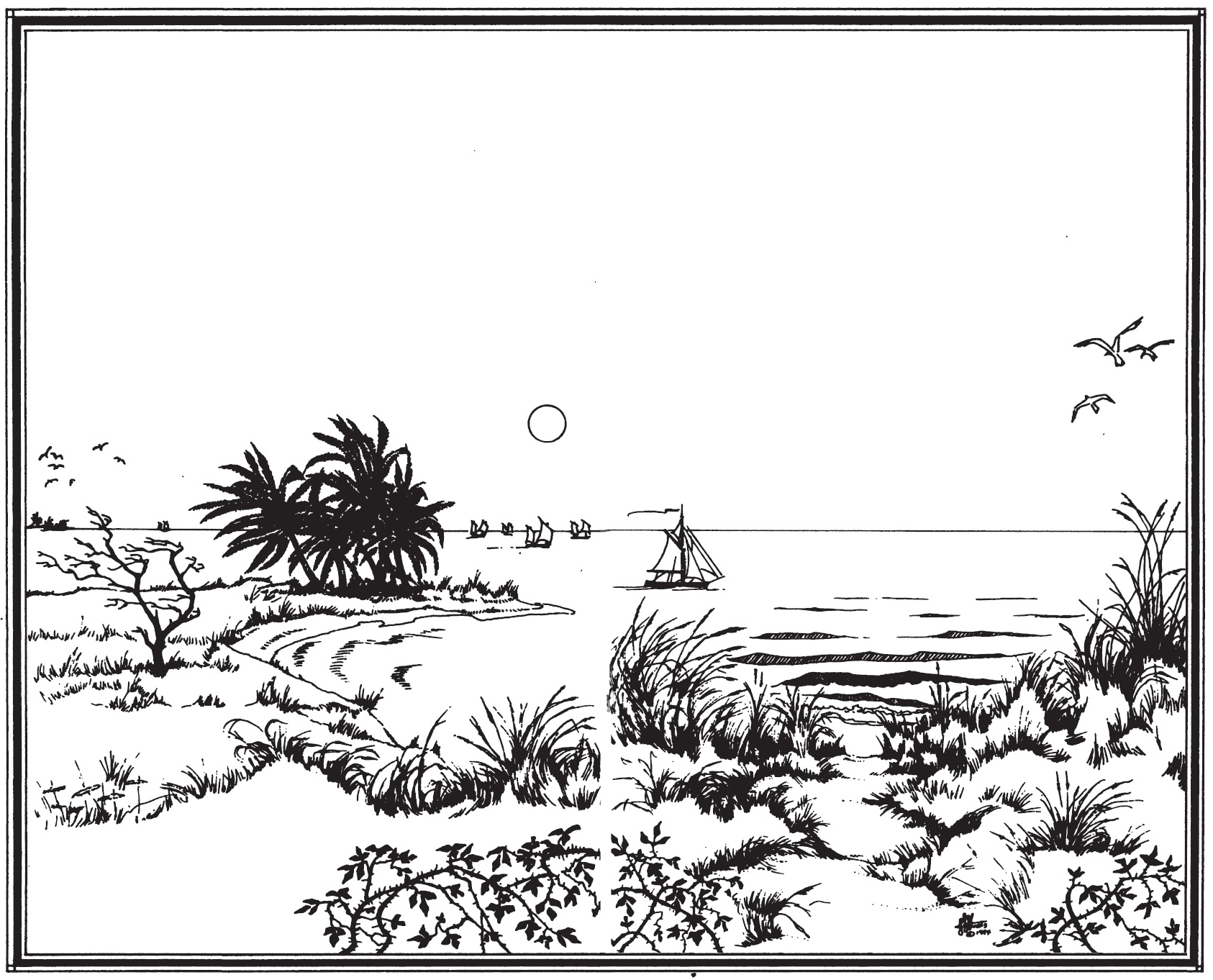

The moment seemed unlikely for happenstance to intrude and shape a spiralling succession of events to upend loyalties and kingdoms. Havish’s coastal landscape with its jagged, shady valleys wore the mottled greens of late spring. Dew still spangled the leaf-tips, touched brilliant by early sunlight. Asandir rode in his shirtsleeves, the dark, silver-banded mantle lately worn for the royal coronation folded inside his saddle pack. Hair of the same fine silver blew uncovered in the gusts that whipped off the sea; that tossed the clumped bracken on the hill crests and fanned gorse against lichened outcrops of quartz rock. The black stud who bore him strode hock-deep in grass, alone beneath cloudless sky. Wildflowers thrashed by its passage sweetened the air with perfume and the jagging flight of disturbed bees.

For the first time in centuries of service, Asandir was solitary, and on an errand of no pressing urgency? The ruthless war, the upsets to rule and to trade that had savaged the north in the wake of the Mistwraith’s imprisonment had settled, if not into the well-governed order secured for Havish, then at least into patterns that confined latent hatreds to the avenues of statecraft and politics. Better than most, Asandir knew the respite was fated not to last. His memories were bitter and hurtful, of the great curse cast by the Mistwraith to set both its captors at odds; the land’s restoration to clear sky bought at a cost of two mortal destinies and the land’s lasting peace.

Unless the Fellowship sorcerers could find means to break Desh-thiere’s geas of hatred against the royal half-brothers whose gifts brought its bane, the freed sunlight that warmed the growing earth could yet be paid for in blood. With the restored throne of Havish firmly under its crowned heir, Asandir at last rode to join his colleagues in their effort to unbind the Mistwraith’s two victims from the vicious throes of its vengeance.

Relaxed in rare contentment, too recently delivered from centuries of sunless damp to take the hale spring earth for granted, he let his spirit soar with the winds. The road he had chosen was years overgrown, little more than a crease that meandered through thorn and brushbrake to re-emerge where the growth was browsed close by deer. Despite the banished mists, the townsmen still held uneasy fears of open spaces, once the sites of forgotten mysteries. Northbound travellers innately preferred to book their passage by ship.

Untroubled by the after-presence of Paravian spirits, not at all disturbed by the foundations of ancient ruins that underlay the hammocks of wild roses, the sorcerer rode with his reins looped. He followed the way without misstep, guided by memories that predated the most weathered, broken wall. His appearance of reverie was deceptive. At each turn, his mage-heightened senses resonated with the natural energies that surrounded him. The sun on his shoulders became a benediction, both counterpoint and celebration to the ringing reverberation that was light striking shadow off edges of wild stone.

When a dissonance snagged in the weave, reflex and habit snapped Asandir’s complaisance. His powers of perception tightened to trace the immediate cause.

Whatever bad news approached from the south, his mount’s wary senses caught no sign. The stallion snorted, shook out his mane, and let Asandir rein him over to the verge of the trail. Long minutes later, a drum roll of galloping hooves startled the larks to songless flight. When the messenger on his labouring mount hove into view, the sorcerer sat his saddle, frowning; while the stud, bored with waiting, cropped grass.

The courier wore royal colours, the distinctive scarlet tabard and gold hawk blazon of the king’s personal service snapped into creases against the breeze. No common message bearer, he owned the carriage of a champion fighter. But the battle-brash courage that graced his reputation was missing as he hauled his horse to a prancing, head-shaking halt.

The man was a fool, who eagerly brought trouble to the ear of a Fellowship sorcerer.

Briskly annoyed, Asandir spoke before the king’s rider could master his uncertainty. ‘I know you were sent by your liege. If my spellbinder Dakar is cause and root of some problem, I say now, as I told his Majesty and the realm’s steward on my departure: there is no possible difficulty that might stem from an apprentice’s misdeeds that your High King’s justice cannot handle.’

The messenger nursed lathered reins to divert his eye-rolling mount from her sidewards crabsteps through the bracken. ‘Begging pardon, Sorcerer. But Dakar got himself drunk. There was a fight.’ Sweating pale before Asandir’s displeasure, he finished in a crisp rush. ‘Your spellbinder’s got himself knifed and King Eldir’s healers say he’ll bleed to death.’

‘Oh, indeed?’ The words bit the quiet like sheared metal. Asandir’s brows cocked up. Features laced over with creases showed a moment of fierce surprise. Then he started his black up from a mouthful of grass and spun him thundering back toward the city.

Alone in the derelict roadway on a sidling, race-bred horse, the royal courier had no mind to linger. He was not clan kindred, to feel at ease in the wild places where the old stones lay carved with uncanny patterns to snag and bewitch a man’s thoughts. The instant his overstrung mare quit her tussle with the bit, he nursed her along at a trot, relieved to be spared the company of a sorcerer any right-thinking mortal knew better than to presume not to fear.

The city known as the jewel of the southwest coast flung an ungainly sprawl of battlements across the crown of a cove. Built over warrens of limestone caves once used as a smuggler’s haven, the architecture reflected twelve centuries of changing tastes, battered as much by storms as by war, and bearing like layers in sediment the mismatched masonry of refortifications and repairs. Sea trade provided the marrow of Ostermere’s wealth. Walls of tawny brick abutted bulwarks of native limestone, scabrous with moss and smothered in lee-facing crannies by salt-stunted runners of wild ivy. The whole overlooked a series of weathered ledges that commanded a west-facing inlet, each tier crusted with half-timber shops and slate-roofed mansions still gay with bunting and gold streamers from celebration of the king’s accession. If the merchant galleys docked along the seaside gates no longer flew banners at their mastheads, if the guards by the harbourmaster’s office had shed ceremonial accoutrements for boiled leather hauberks and plain steel, a charge of excitement yet lingered.

In all the realm, this city had been honoured as the royal seat until the walls at Telmandir could be raised out of ruin and restored to the splendours of years past. An alertness like frost clung to the men hand-picked for the royal guard. Out of pride for their youthful sovereign, they had the unused north postern winched open and the shanty market that encroached upon its bailey cleared of beggars and squatters’ stalls when Asandir’s stallion clattered through.

In a courtyard still gloomy under overhanging tenements, the sorcerer dismounted. He tossed his reins to a barefoot boy groom grown familiar with the stud through the months of change as town governance had been replaced by sovereign monarchy. Without pause for greeting, Asandir strode off, scattering geese and a loose pig from the puddled run-off by the wash house. He dodged through men in sweaty tunics who unloaded tuns from an ale dray, avoided a bucket-bearing scullion and crossed without mishap through the tumbling brown melee of a deerhound bitch’s cavorting pups.

Just arrived, all but brushed aside with the same brisk lack of ceremony, the captain of Ostermere’s garrison pumped on fat legs to join the sorcerer. A capricious gust snatched his unbelted surcoat. Clutching scarlet broadcloth with both hands to escape getting muffled by his clothing, he relayed facts with a directness at odds with his untidy turnout.

‘It was a damnfool accident, the Mad Prophet so drunken he could barely stand upright. He’d visited the kitchens to meet a maid he claimed he’d an assignation with. Muddled as he was, he kissed the wrong doxy. Her husband came in at just the right time to lose his temper.’ The city captain gave a one-handed shrug, his brows beetled over his beefy nose. ‘The knife was handy on the butcher’s block, and the wound-’ Asandir cut him off. ‘The details won’t matter.’ He reached the servants’ postern, flung it open fast enough to whistle air, and added, ‘Your gate guards are missing their gold buttons.’

Ostermere’s ranking captain swore. An unlikely, swordsman’s agility allowed him to nip through the fast-closing panel. ‘The meatbrains got themselves fleeced at dice. Not a man of them will own up, but since you ask, there were bystanders who fingered Dakar as the instigator.’

‘I thought so.’ Light through an ancient arrow-slit sliced across Asandir’s shoulders as he traversed the corridor behind the pantries and began in long strides to climb stairs. Instructions trailed echoing behind him. ‘Inform your royal liege I’m here. Ask if he’ll please attend me at once in Dakar’s bedchamber.’

Dismissed with one foot raised to mount an empty landing, the city captain spun about. ‘Ask my liege, indeed! I know a command when I hear one. And I’d beg on my knees for Dharkaron Avenger’s own judgement before I’d shift places with Dakar.’

From far above, Asandir’s voice cracked back in crisp reverberation. ‘For the Mad Prophet’s transgressions this time, Dharkaron’s judgement would be too merciful.’

High-browed, intelligent, and shrewdly even-tempered for a lad of eighteen years, King Eldir arrived in a state of disarray as striking as his ranking captain’s. Swiping back tousled brown hair, sweat-damp from a running ascent of several flights of tower stairs, he heaved off cloak, sash and tabard, and shed a gold-trimmed load of state velvets without apology onto a bench in a lover’s nook. In just dread of Asandir’s inquiry, he jerked down the tails of an undertunic threadbare enough to have belonged to an apprentice labourer and mouthed exasperated excuses to himself. ‘I’m sorry. But the drawers the tailors’ guild sent had enough ties and eyelets to corset a whore, and too much lace makes me itch.’

Eldir broke off, embarrassed. The sorcerer he hastened to meet was not attending his injured charge, but standing stone-still in the hallway, one shoulder braced against the doorjamb and his face bent into shadow.

The young king paled in dismay. ‘Ath’s mercy! We reached you too late to help.’

Asandir glanced up, eyes bright. ‘Certainly not.’ He inclined his head toward the door. Muffled voices issued from the other side, one male and laboured, another one female, bewailing misfortune in lisping sympathy.

Eldir’s interest quickened. Even in extremis, it appeared the infamous Mad Prophet had pursued his ill-starred assignation. Then, practical enough to restrain his wild thoughts, Havish’s sovereign sighed in disappointment. ‘You’ve healed him already, I see.’

The sorcerer shook his head. Dire as oncoming storm, he spun in the corridor, tripped the latch without noise and barged into Dakar’s bedchamber.

The panel opened to reveal a pleasant, sunwashed alcove, cushioned chairs carved with grape clusters, and a feather mattress piled with quilts. The casement admitted a flood of ocean air lightly tainted by the tar the chandlers sold to black rigging. Swathed like a sausage in eiderdown, a chubby man lay with a face wan as bread dough and a beard like the curled fringe on a water-spaniel. Caught leaning over to kiss him, the pretty blonde kitchen maid with the knife-wielding husband murmured into his ear, ‘I will grieve for you and pray to Ath to preserve your undying memory.’

‘Which won’t be the least bit necessary!’ Asandir cracked from his planted stance by the doorway.

At his shoulder, Eldir started.

The maid snapped erect with a squeal and the quilts jerked, the victim beneath galvanized to a fish-flop start of surprise. A fondling hand recoiled from under a froth of lace petticoats as Dakar swivelled cinnamon eyes, widened now to rolling rings of white.

The tableau endured a frozen moment. Already pale, the sorcerer’s wounded apprentice gasped a bitten-off curse, then to outward appearance fell comatose.

‘Out!’ Asandir jerked his chin toward the girl, who cast aside dignity, gathered her skirts above her knees and fled trailing unlaced furbelows.

As her footsteps dwindled down the corridor, the sorcerer kicked the door closed. A paralysed stillness descended, against which the rumble of ale tuns over cobbles seemed to thunder off the courtyard walls outside. Beyond the opened shutter, the call of the changing watch drifted off the wall walks, mingled with the bellow of the baker’s oaths as he collared a laggard scullion. The yap of gambolling puppies, the grind of wagons across Ostermere market and the screeling cries of scavenging gulls seemed unreal, even dreamlike, before the stark tension in the room.

Asandir first addressed the king, who waited, frowning thoughtfully. ‘Although I ask that the secrets of mages be kept from common knowledge in your court, I would have you understand just how far my apprentice has misled you.’ He stepped to Dakar’s bedside and with no shred of solicitude, ripped away quilting and sheets.

Dakar bit his lip, poker stiff, while his master yanked off the sodden dressing that swaddled the side the baking girl’s husband had punctured.

The linen came free, gory as any bandage might be if pulled untimely from a mortal wound. Except the flesh beneath was unmarked.

King Eldir gaped in surprise.

Dakar,’ Asandir informed, ‘is this day five hundred and eighty-seven years old. He has longevity training. As you see, the suffering of wounds and illness is entirely within his powers to mend.’

‘He was in no danger,’ Eldir stated in rising, incredulous fury. He folded his arms, head tipped sidewards, while skin smudged with the first shaved trace of a beard deepened to a violent, fresh flush. That moment, he needed no crown to lend him majesty. ‘For whim, the realm’s champion was sent out and told to run my fastest mare to death to fetch your master?’

Naked and pink and far too corpulent to cower into a feather mattress, Dakar shoved stubby hands in the hair at his temples. He licked dry lips, flinched from Asandir and squirmed. ‘I’m sorry.’ His shrug was less charming than desperate.

‘Were you my subject, I’d have your life.’ Eldir flicked a glance at the sorcerer, whose eyes were like butcher’s steel fresh from the whetstone. ‘Since you’re not my feal man, regretfully, I can’t offer that kindness.’

Sweat rolled through Dakar’s fingers and snaked across his plump wrists. His breathing came now in jerks, while lard at his knees jumped and quivered.

Eldir inclined his head toward Asandir. ‘Perhaps I should wait for you without?’ Mindful of his dignity, he side-stepped toward the door.

Alone and defenceless before his master, Dakar covered his face. Through his palms, he said, ‘Ath! If it’s to be tracing mazes through sand grains again, for mercy, get on with your traps and be done with me.’

That wasn’t what I had in mind.’ Asandir advanced to the bedside. He said something almost too soft to hear, cut by a wild, ragged cry from Dakar that trailed off to snivelling, then silence.

Eldir rushed his step to shut the door. But the panel was caught short before it slammed, and Asandir stepped through. He set the latch with steady fingers, turned around to regard the King of Havish, and said succinctly, ‘Nightmares. They should occupy the Mad Prophet at least until sundown. He’ll emerge hungry, and I sadly fear, not in the least bit chastened.’ Between one breath and the next, the sorcerer recovered his humour. ‘Do I owe you for more than your guardsmen’s allotment of gold buttons?’

‘Not me.’ Eldir sighed, strain and uncertainty returned to pull at the corners of his mouth. ‘The oldest son of the town seneschal staked his mother’s jewellery on bad cards, and I’m not sure exactly who started the dare. But the cook’s fattened hog escaped its pen. The creature wound up in a warehouse and spoiled the raw wool consigned for the dyers at Narms. Truth to tell, the guild master’s council of Ostermere is howling for Dakar’s blood. My guard captain held orders to clap him in chains when the fight broke out in the kitchen.’

‘I leave my apprentice to protect you for one day and find you exhausted by a hard lesson in diplomacy.’ Asandir’s grin flashed like a burst of sudden sunlight. He laid a steering hand on the royal shoulder and started off down the corridor. ‘From this moment, consider my apprentice removed from the realm’s concerns. Your steward Machiel should be able to guard your safety well enough, since you’ve managed to hold Havish secure through Dakar’s irresponsible worst. I’ve decided exactly what I shall do with our errant prophet and I doubt he takes it well.’

‘You’d punish him further?’ The habits of an unassuming boyhood still with him, Eldir paused by the window-seat to gather his discarded state finery. ‘What could be worse than harrowing the man with uninterrupted bad dreams?’

‘Very little.’ Asandir’s eyes gleamed with sharp irony. ‘When Dakar awakens, you will send him from court on a travelling allowance I’ll leave for his reassignment. Tell him his task is to keep Prince Arithon of Rathain from getting murdered by Etarra’s new division of field troops.’

Eldir stopped cold in the corridor. After five years, accounts were still repeated of the bloody war that had slaughtered two thirds of Etarra’s garrison and left the northern clansmen feal to Arithon nearly decimated in the cause of defending his life. Motivated by a feud between half-brothers embroiled in bitter enmity; lent deadly stakes by the same powers of sorcery that had once defeated the Mistwraith; and fanned hotter by age-old friction still standing elsewhere between clanborn and townsman, the conflict had since brought the unified opposition of every merchant city in Rathain. The prince with blood-right to rule there was a marked and hunted man. Every trade guild within his own borders was eager to skewer him in cold blood.

Havish’s emphatically neutral sovereign made a sound between a cough and a grunt as he considered Dakar’s penchant for trouble appended to the man called Master of Shadow, that half of the north wanted dead. ‘I shouldn’t presume to advise, but isn’t that fairly begging fate to get Rathain a killed prince?’

‘So one might think,’ Asandir mused, not in the least bit concerned. ‘Except Arithon s’Ffalenn needs none of Dakar’s help just now. On the contrary, he’s perhaps the one man alive who may be capable of holding the Mad Prophet to heel. The match should prove engagingly fascinating. Each man holds the other in the utmost of scorn and contempt.’

Petition

The next event in the widening chain of happenstance provoked by the Mistwraith’s bane arose at full summer, when visitors from Rathain’s clan survivors sought audience with another high chieftain in the neighbouring realm to the west. Hailed as she knelt on damp pine needles in the midst of dressing out a deer, Lady Maenalle bent a hawk-sharp gaze on the breathless messenger.

‘Fatemaster’s justice, why now?’ Bloodied to the wrists, her knife poised over a welter of steaming entrails, the woman who also shouldered the power of Tysan’s regency shoved up from her knees with a quickness that belied her sixty years. Feet straddled over the half-gutted carcass, the man’s leathers she preferred for daily wear belted to a waist still whipcord trim, Maenalle pushed back close-cropped hair with the back of her least sticky wrist. She said to the boy who had jogged up a mountainside to fetch her, ‘Speak clearly. These aren’t the usual clan spokesmen we’ve received from Rathain before?’

‘Lady, not this time.’ Sure her displeasure boded ill for the scouts, whose advance word now seemed negligently scant on facts, the boy answered fast. ‘The company numbers fifteen, led by a tall man named Red-beard. His war captain Caolle travels with him.’

‘Jieret Red-beard? The young s’Valerient heir?’ Grim in dismay, Maenalle cast a bothered glance over her gore-spattered leathers. ‘But he’s Deshir’s chieftain, and Earl of the North!’