Полная версия

The Blackmailers: Dossier No. 113

COPYRIGHT

Published by COLLINS CRIME CLUB

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in French as Dossier No.113 by E. Dentu 1867 Translated as The Blackmailers by Ernest Tristan 1907 Published by The Detective Story Club Ltd for Wm Collins Sons & Co. Ltd 1929 Introduction Richard Dalby 2016

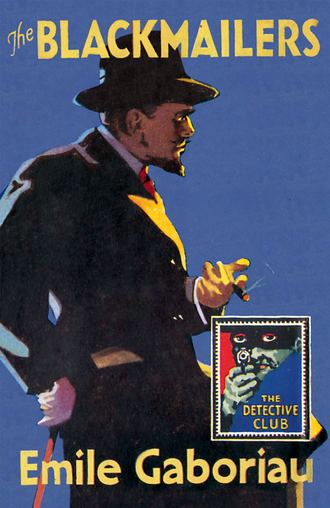

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 1929, 2016

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008137519

Ebook Edition © April 2016 ISBN: 9780008137526

Version: 2016-02-19

CONTENTS

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

CHAPTER XV

CHAPTER XVI

CHAPTER XVII

CHAPTER XVIII

CHAPTER XIX

CHAPTER XX

CHAPTER XXI

CHAPTER XXII

CHAPTER XXIII

CHAPTER XXIV

CHAPTER XXV

ABOUT THE BOOK

THE DETECTIVE STORY CLUB

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

INTRODUCTION

ÉMILE Gaboriau’s ingenious creation Monsieur Lecoq was the first important literary detective to be featured in a series of novels during the 1860s. Published midway between Edgar Allan Poe’s three celebrated stories featuring C. Auguste Dupin (including ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’) in the early 1840s and Arthur Conan Doyle’s first Sherlock Holmes novel in 1887, Monsieur Lecoq was also an exact contemporary of Sergeant Cuff in The Moonstone by Wilkie Collins (1868), considered to be Britain’s first classic detective novel.

Gaboriau moved ahead of his contemporaries by focusing attention on the gathering and interpretation of evidence in the detection of crime. Historically he is second only to Poe in creating pure detective fiction, by writing the first novels in which the nature of the crime, the role of the detective, the misdirections, the reader participation and the solution are all carried through successfully in the contemporary manner, a great inspiration to all who followed in this genre.

Émile Gaboriau was born in the town of Saujon, France, on 9 November 1832, the son of a notary. He spent seven years in the cavalry before settling in Paris, where he wrote poetic mottoes for birthday cakes and songs for street singers.

He then became assistant, secretary and ghost-writer to Paul Féval, author of widely-read criminal romances for feuilletons (inserted as supplements in daily newspapers). Gaboriau gathered much of his material in police courts for Féval, and in 1858 broke away to begin work on his own serialised novels.

After writing seven popular romances, Gaboriau produced his first detective novel, L’Affaire Lerouge, which began its newspaper serialisation in September 1865, and was published in book form the following year. In this story, Gévrol, chief of the detective police in the Paris Sûreté, is in charge, but the major detection is provided by Père Tabaret, an amateur consultant who explains his methods to the young Lecoq. Tabaret has studied the literature of crime for a long time and worked by ratiocination, or precise thinking, to solve a very deceptive crime, said to have been based on a contemporary murder.

Lecoq began in L’Affaire Lerouge as a minor detective with a shady past who had previously contemplated illegal methods of gaining wealth before joining the Sûreté. His career was inspired and closely based on the life and memoirs of the real-life detective Eugène François Vidocq (1775–1857), who also joined the Sûreté after a life of crime.

After his début, Lecoq had much more important leading roles in Le Crime d’Orcival (1867), Le Dossier No.113 (1867), Les Esclaves de Paris (1868, initially in two volumes), and Monsieur Lecoq (1869, also in two volumes). These enthralling mysteries ensured that Lecoq gained countless admirers throughout Europe, including the statesmen Benjamin Disraeli and Otto von Bismarck. As Gaboriau’s reputation grew, so were his novels translated and published in the UK, but none were more successful than the bestselling Lecoq quintet, issued by Routledge in the summer of 1887 in cheap paperback and yellowback editions under the titles The Widow Lerouge, The Mystery of Orcival, File No.113, The Slaves of Paris and Monsieur Lecoq.

In addition to becoming a master of disguise, Lecoq developed valuable crime-fighting techniques, such as using plaster to make impressions of footprints and devising a test of when exactly a bed has been slept in. He was always a supreme master of excavating and analysing deeply-buried vital clues. Perhaps it was no coincidence that the first Sherlock Holmes novel, A Study in Scarlet, followed shortly after the Routledge paperbacks, at Christmas in the same year.

Émile Gaboriau died suddenly on 28 September 1873, supposedly of ‘overwork’, aged only 40, having written 21 novels in thirteen years (fourteen of them in his last seven years of life). He described his works as romans judiciaires, a crime-mystery form much imitated by writers in the century to come.

The third Monsieur Lecoq novel, Le Dossier No.113, was first translated into English in 1875 and published by A. L. Burt in New York. The work was copyrighted to James R. Osgood & Co., but the identity of the translator was not given. Running to 145,000 words, the English translation was literal and rather cumbersome, although the book proved to be popular and was reissued by a number of publishers many times over the next four decades.

In 1907, a new translation by Ernest Tristan was published by Greening & Co. under the more evocative title The Blackmailers, a complete but more efficient interpretation of the book that halved its page count. It was this version that William Collins Sons & Co. of Glasgow later released in their rapidly expanding series of Pocket Classics. Also selected as the sixth book in Collins’ new Detective Story Club imprint, it was published in September 1929 with typical fanfare:

‘Émile Gaboriau is France’s greatest detective writer. The Blackmailers is one of his most thrilling novels, and is full of exciting surprises. The story opens with a sensational bank robbery in Paris, suspicion falling immediately upon Prosper Bertomy, the young cashier whose extravagant living has been the subject of talk among his friends. Further investigation, however, reveals a network of blackmail and villainy which seems as if it would inevitably close round Prosper and the beautiful Madeleine who is deeply in love with him. Can he prove his innocence in the face of such damning evidence?’

The story was filmed in Hollywood in 1932 under the older title File No.113, starring Lew Cody as the subtly renamed ‘Le Coq’.

Although Gaboriau’s fame and reputation were inevitably overshadowed by newer crime writers after his death, he was later championed by several discerning critics including the novelists Valentine Williams (in a 1923 landmark essay, ‘Gaboriau: Father of the Detective Novel’) and Arnold Bennett, who praised all the Lecoq novels in 1928, stating that they are ‘brilliantly presented and, besides the detection and crime-solving, Gaboriau was able to provide a really good, sound and emotional novel’.

After 150 years, Gaboriau’s novels will always deserve to be savoured, appreciated and rediscovered by connoisseurs of early detective fiction.

RICHARD DALBY

January 2016

CHAPTER I

THERE appeared in all the evening papers of Tuesday, February 28, 1865 the following paragraphs:

‘An extensive robbery from a well-known banker of the city, M. André Fauvel, this morning caused great excitement in the neighbourhood of the Rue de Provence. The thieves with extraordinary skill and daring succeeded in entering his office, forcing a safe, which was believed to be burglar-proof, and carrying off the enormous sum of 350,000 francs in banknotes.

‘The police, who were at once informed of the robbery, displayed their usual zeal, and their efforts have been crowned with success. One of the employees, “P.B.”, has been arrested; it is to be hoped that his accomplices will soon be in the clutches of the law.’

During four whole days Paris talked of nothing but this robbery.

Then other serious events happened, an acrobat broke his leg at the circus, a young actress made her début at a little theatre, and the paragraph of February 28 was forgotten.

But this time the newspapers, perhaps on purpose, had been badly or inaccurately informed.

A sum of 350,000 francs had, it was true, been stolen from M. André Fauvel, but not in the way indicated. An employee, in fact, had been detained for a time, but no real charge was made against him. The robbery, though of unusual importance, remained unexplained if not inexplicable.

Here are the facts as related in detail in the report of the inquiry.

CHAPTER II

THE André Fauvel bank premises, No. 87 Rue de Provence, is an important building and with its large staff looks almost like a Government office.

The counting-house of the bank is on the ground floor, and the windows which look out into the street are fitted with bars, so thick and close together as to discourage all attempts at robbery.

A large glass door opens into an immense vestibule in which, from morning to night, three or four messengers are stationed.

To the right are the offices, into which the public are admitted, and a passage leading to the entrance to the strong room. The correspondence, ledger and accountant general’s departments are on the left.

At the rear there is a little courtyard covered in with glass, into which seven or eight doors open. At ordinary times they are not used, but at certain times they are indispensable.

M. André Fauvel’s private room is on the first floor in a fine suite of apartments.

This private room communicates directly with the counting-house by a little black staircase, very narrow and steep, which descends into the chief cashier’s room.

This room, which is called the strong room, is protected from a sudden attack, and from a siege almost, for it is armour plated like a battleship.

Thick plates of sheet-iron protect the doors and the partitions, and a strong grating obstructs the chimney.

Inside these, let into the wall with enormous cramps, is the safe; one of those fantastic and formidable objects which make a poor devil, who can easily carry his fortune in his purse, dream.

The safe, a fine specimen by Becquet, is two metres high and one and a half broad. Made entirely of wrought-iron it is built with three walls, and inside is divided into isolated compartments in case of fire.

One tiny key opens this safe. But the opening with the key is quite an unimportant business. Five movable steel buttons, upon which are engraved all the letters of the alphabet, constitute the secret of its strength. Before putting the key in the lock it is necessary to be able to replace the letters in that order in which they were when the safe was locked.

There, as elsewhere, the safe was closed with a word which was changed from time to time.

This word was only known to the head of the firm and the cashier. Each of them had a key.

With such a property, though possessed of more diamonds than the Duke of Brunswick, a person ought to be able to sleep soundly.

There appears to be only one risk, that of forgetting the ‘Open Sesame’ of the iron door.

On the morning of February 28 the staff arrived as usual.

At half past nine when they were all attending to their duties, a very dark man of uncertain age and military bearing, in deep mourning, entered the office nearest the strong room, in which five or six of the staff were at work. He asked to see the chief cashier.

He was told that the cashier had not yet arrived and that the strong room did not open till ten, a large notice to this effect being displayed in the vestibule.

This reply seemed to disconcert and annoy the newcomer.

‘I thought,’ he said in a dry almost impertinent tone, ‘that I should find someone here to see me, after arranging with M. Fauvel yesterday. I am Count Louis de Clameran, ironmaster at Oloron. I have come to withdraw 300,000 francs deposited here by my brother, whose heir I am. It is surprising that you have not received instructions.’

Neither the title of the noble ironmaster nor his business seemed to touch the staff.

‘The cashier has not yet come,’ they repeated, ‘we can do nothing.’

‘Then let me see M. Fauvel.’ After a certain amount of hesitation, a young member of the staff named Cavaillon, who worked near the window, said:

‘He always goes out about this time.’

‘I shall go then,’ said M. de Clameran.

He went out without saluting or raising his hat, as he had done when he came in.

‘Our client is not very polite,’ said Cavaillon, ‘but he has no luck, for here is Prosper.’

The chief cashier, Prosper Bertomy, was a fine fellow of thirty, he was fair with blue eyes and dressed in the latest style.

He would have been very good-looking but for an exaggerated English manner, making him cold and formal at will, and an air of conceit, which spoiled his naturally laughing face.

‘Ah, here you are,’ said Cavaillon. ‘Someone has been asking for you already!’

‘Who was it? An ironmaster, was it not?’

‘Precisely.’

‘Ah, well, he will came back. Knowing I should be late this morning, I made preparations yesterday.’ Prosper having opened the door of his room as he spoke went in and shut it after him.

‘He is a cashier who does not worry,’ one of the staff said. ‘The chief has had twenty scenes with him for being late, and he takes as much notice as he does of the year forty.’

‘He is quite right, too, for he gets all he wants out of the chief.’

‘Besides, how does he look in the morning? Like a fellow who leads a terrible life and enjoys himself every night. Did you notice his ghastly look this morning?’

‘He must have been playing again, like he did last month. I found out from Couturier that he lost 1,500 francs at a single sitting!’

‘Does he neglect business?’ asked Cavaillon. ‘If you were in his place—’

He stopped short. The strong room door opened, and the cashier came in tottering.

‘I have been robbed!’ he cried.

Prosper’s look, his raucous voice, his tremors, expressed such frightful anguish, that all the staff got up and rushed to him. He almost fell into their arms, he could not stand, he felt ill and had to sit down.

But his colleagues surrounded him, all asking questions at the same time and pressing him to explain.

‘Robbed,’ they said; ‘where, how, by whom?’

Prosper gradually recovered.

‘All I had in the safe,’ he replied, ‘has been taken.’

‘Everything?’

‘Yes, three packets of a hundred one thousand franc notes, and one of fifty. The four packets were wrapped round by a piece of paper and tied together.’ With the rapidity of a flash of lightning the news of the robbery spread through the bank, and the room was quickly filled with a curious crowd.

‘Has the safe been forced?’ Cavaillon asked Prosper.

‘No, it is intact.’

‘Well, then?’

‘It is none the less a fact that last evening I had 350,000 francs and this morning they are gone.’ Everybody was silent; one old servant did not share the general consternation.

‘Do not lose your head like this, M. Bertomy,’ he said. ‘Perhaps the chief has disposed of the money?’

The unfortunate cashier jumped at the idea.

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘you are right; it must be the chief.’

Then, after reflection, he went on in a deeply discouraged tone:

‘No, it is not possible. Never during the five years I have been cashier has M. Fauvel opened the safe without me! Two or three times he has needed funds and has waited for me, or sent for me rather, than touch it in my absence.’

‘That does not matter,’ objected Cavaillon.

‘Before distressing ourselves, we must let him know.’ But M. André Fauvel knew already. A clerk had gone up to his private room and told him what had taken place.

Just as Cavaillon suggested going to tell him he appeared.

M. André Fauvel was a man of about fifty, of medium height, and hair turning grey, who walked with a slight slouch. He had an air of benevolence, a frank open face and red lips. He was born near Aix, and in times of excitement he spoke with a slight provincial accent.

The news he had heard had disturbed him, for he was very pale.

‘What is the matter?’ he asked the employees, who respectfully drew back as he approached. The cashier got up and advanced to meet him.

‘Sir,’ he began, ‘yesterday I sent for 350,000 francs from the bank to make the payment today of which you are

aware.’

‘Why yesterday?’ the banker interrupted ‘I have told you a hundred times to wait till the day.’

‘I know, sir, I was wrong, but the mischief is done. The money has disappeared, without the safe being forced.’

‘You must be mad or dreaming!’ cried M. Fauvel.

Prosper answered almost without trouble or rather with the indifference of one in a hopeless position.

‘I am not mad nor dreaming. I am telling you the truth.’

This calmness seemed to exasperate M. Fauvel. He seized Prosper by the arm and shook him, as he said:

‘Speak! Speak! Who opened the safe?’

‘I cannot say.’

‘Only you and I knew the word; only you and I had the key.’

After these words, which were almost an accusation, Prosper gently freed his arm and continued:

‘No one but I could have taken the money, or you.’

‘You rascal!’ the banker cried with a threatening gesture. Just then there was the noise of an argument outside. A client insisted upon coming in. It was M. de Clameran. He entered with his hat on and said:

‘It is after ten, gentlemen.’

No one replied, but he espied the banker and went to him.

‘I am delighted to see you, sir,’ he said. ‘I called once before this morning, but the cashier had not arrived and you were out.’

‘You are mistaken, sir. I was in my private room.’

‘This young man,’ pointing to Cavaillon, ‘told me so; but on my return just now I was refused admittance. Will you be good enough to tell me whether I can withdraw my money or not.’

M. Fauvel listened to him, trembling with rage the while, and then replied:

‘I shall be glad of a little delay. I have just become aware of a theft of 350,000 francs.’ M. de Clameran bowed ironically. ‘Shall I have long to wait?’ he asked.

‘The time it will take to send to the bank,’ M. Fauvel said, as he turned to his cashier and instructed him to write a note and send a messenger as quickly as possible to the bank.

Prosper made no movement.

‘Don’t you hear me?’ the banker shouted.

The cashier shuddered, as if awakening out of a dream, and answered:

‘That is useless, there is not a hundred thousand francs to your credit.’

At that time Paris was in a state of financial panic. Many old and honourable firms had gone to the wall, ruined by the wave of speculation which had swept over the country.

M. Fauvel noticed the impression produced on the ironmaster and, turning to him, said:

‘Have a little patience, sir, I have plenty of other securities. I shall be back in a minute.’

He went upstairs to his private room and returned in a few minutes with a letter and a packet of securities in his hand.

‘Take this, he said to Couturier, one of the clerks, ‘and go to Rothschild’s with this gentleman. Give them the letter and they will hand you 300,000 francs, which you are to give to this gentleman.’

The ironmaster seemed anxious to excuse his impertinence, but the banker cut him short.

‘All I can do,’ he said, ‘is to offer you my apologies. In business a man has neither friends nor acquaintances. You are quite within your rights. Follow my clerk and you will receive your money.’

Turning to the clerks who had gathered round, he ordered them to get on with their work, and then found himself face to face with Prosper, who had remained standing quite still.

‘You must explain,’ he said; ‘go into your room.’

The cashier did so without a word, and was followed by his employer. The room showed no signs of the robbery having been committed by anyone not familiar with the place. Everything was in order, the safe was open, and upon the upper shelf was a little gold, which had been either forgotten or disdained by the thieves.

‘Now we are alone, Prosper,’ M. Fauvel, who had recovered his usual calm, began, ‘have you nothing to tell me?’

The cashier trembled but replied:

‘Nothing, sir; I have told you everything.’

‘What, nothing? You persist in this absurd story which no one will believe! Trust me, it is your only chance. I am your employer, but I am your friend as well. I cannot forget that you have been with me for fifteen years and done good and loyal service.’

Prosper had never before heard his employer speak so gently and in such a fatherly way, and an expression of surprise came into his face.

‘Have I not,’ continued M. Fauvel, ‘always been like a father to you? You were even a member of my family circle for a long time, till you wearied of that happy life.’

These souvenirs of the past made the unhappy cashier burst into tears, but the banker continued:

‘A son can tell his father everything. Am I not aware of the temptations which assail a young man in Paris? Speak, Prosper, speak!’

‘Ah, what would you have me say?’

‘Tell the truth. Even an honest man can make a mistake, but he always redeems his fault. Say to me: “Yes, the sight of the gold was too much for me, I am young and passionate.”’

‘I,’ Prosper murmured. ‘I—!’

‘Poor child,’ the banker said sadly, ‘do you think I am ignorant of the life you have been leading? Your fellow clerks are jealous of your salary of 12,000 francs a year. I have learned of every one of your follies by an anonymous letter. It is quite right, too, that I should know how the man lives who is entrusted with my life and honour.’