Полная версия

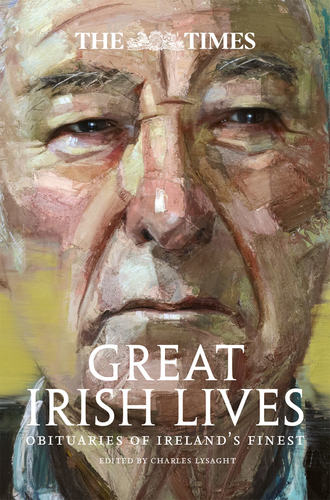

The Times Great Irish Lives: Obituaries of Ireland’s Finest

A whole chapter of legend has grown up about Lord Morris’s name and his reputation as a wit. Countless stories are told of his sharp sayings, some of them authentic and most of them characteristic. Perhaps none are more striking than some of the utterances attributed to him when he sat on the Bench in Ireland. During the earlier developments of Fenianism some Irish Judges expended a vast amount of rhetorical indignation on the puny traitors of that day. Morris dealt with them in a different fashion. He wasted no words upon them, but dismissed their futile folly with a moderate sentence and with cutting contempt. In a case where some young farmer’s sons were tried on a charge of illegal drilling and carrying arms by night, Morris said:- “There you go on with your marching and counter-marching, making fools of yourselves, when you ought to be out in the fields, turning dung.” On another occasion, when an eloquent advocate had extenuated some criminal act on the ground that “the people” were in sympathy with the offenders, the Chief Justice remarked, “I never knew a small town in Ireland that hadn’t a black-guard in it who called himself ‘the people.’” Of trial by jury in the sister island he had no very high opinion. “In the West,” he said, “the Court is generally packed with people whose names all begin with one letter, Michael Morris on the Bench, ten men of the name of Murphy and two men of the name of Moriarty in the jury-box, and two other Moriartys in the dock, and the two Moriartys on the jury going in fear of their lives of the ten Murphys if they don’t find against their own friends.”

As Chief Justice he had a high regard for the dignity and independence of his own Court, and especially resented any claim on the part of the Treasury to interfere. Once, it is said, a most distinguished official was sent over from Whitehall to Dublin, after a long correspondence on the side of the Department about the expenditure of fuel in the Courtrooms and Judge’s chamber, to obtain the answer that the vigilant guardians of the public purse had failed to extract in writing. He was received politely by the Chief Justice, who said that he would put him in communication with the proper person; and, ringing the bell, which was answered by the elderly female who acted as Court-keeper, he remarked, as he turned on his heel and left the room, “Mary, this is the man that’s come about the coals.” Shortly after the Land Act of 1881 became law a very important case was carried to the Court of Appeal, of which Morris, as Chief Justice of the Common Pleas, was an ex officio member. Morris was not summoned, and, meeting the Lord Chancellor in the street, he expressed his surprise. The Chancellor, with some embarrassment, explained that he had not wished to put the Chief Justice to inconvenience, that he had summoned a sufficient number of Judges to constitute the tribunal, and that, in fact, there were not chairs enough on the bench of the Court of Appeal to accommodate any more. “Oh!” (said Morris, according to this story). “That need make no difference. I’ll bring my own chair out of my own Court, and I’ll form my own opinion and deliver my own judgment, Lord Chancellor!” In the early days of the Home Rule policy the Chief Justice, it is said, was a guest at a great official banquet in Dublin, where a lady of high position, full of enthusiasm for Mr Gladstone’s latest transmigration, asked him whether the great majority of those present were not ardent Home Rulers. “Indeed, Lady,” said Morris, “I suppose that, with the exception of his Excellency and yourself, and, perhaps, half a dozen of the servants, there aren’t three in the room!”

Lord Morris and Killanin married, in 1860, Anna, daughter of the Hon. G. H. Hughes, Baron of the Court of Exchequer in Ireland. By her he had four sons and six daughters. The eldest son, Martin Henry FitzPatrick, a graduate of the University of Dublin, a barrister of Lincoln’s Inn, succeeds, on his father’s death, to the Barony of Killanin and to the baronetcy. The life peerage of Lord Morris of Spiddal ceases, of course, to exist.

* * *

ARCHBISHOP CROKE

23 JULY 1902

DR THOMAS WILLIAM CROKE, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Cashel and Emly – perhaps the most remarkable Irish ecclesiastic since the death of Cardinal Cullen, though there was little in common between the two men – was born close to the town of Mallow, county Cork, on May 19, 1824. His people were well-to-do farmers. Though his mother was a Protestant, he was destined from an early age by his uncle, who took charge of his education, for the priesthood. He was never in Maynooth, the great training college of the Irish priesthood, but spent ten years in colleges on the Continent established during the operation of the Penal Laws for the education of priests intended for the mission in Ireland and Great Britain. At the age of 14, he entered the Irish College in Paris, and spent six years there; another year was passed in a college in Menin, in Belgium, and after an additional three years in the Irish College in Rome he obtained the degree of Doctor of Divinity, and was ordained priest in 1848. Then for brief periods he was Professor in the Diocesan College, Carlow, and in the Irish College, Paris, after which he returned to his native diocese of Cloyne, Cork, as a missionary priest. In 1858 he was appointed president of St Colman’s College, Fermoy; after seven years he returned to the mission as parish priest of Doneraile. In 1870, when he was 45 years of age, he was appointed by the Pope, on the nomination of Cardinal Cullen, to the bishopric of Auckland, New Zealand. In 1875 the bishopric of Cashel and Emly became vacant. The parish priests of the see met, as usual, to propose three names – dignissimus, dignior, dignus – from whom the Pope was to select the Archbishop. But on the recommendation of Cardinal Cullen the three names were set aside by the Holy See, and Dr Croke was recalled from New Zealand to take charge of the Archdiocese of Cashel and Emly. He was received with extreme coldness by the priests; but a patriotic oration he delivered at the O’Connell Centenary in August, 1875, made him extremely popular. He was thence known as “the patriot Archbishop.”

In the early fifties, while he was a curate in the diocese of Cloyne, Dr Croke took an active part in the land agitation for “the three F’s” – fixity of tenure, fair rents, and free sale – conducted by Gavan Duffy. The movement did not long survive. It was deserted by most of those who had created it. Gavan Duffy, describing Ireland as like “a corpse on the dissecting table,” resigned his seat in Parliament and emigrated to Victoria. Before his departure Dr Croke wrote him a letter, which thus concluded:- “For myself I have determined never to join any Irish agitation, never to sign any petition to Government, and never to trust to any one man or body of men, living in my time, for the recovery of Ireland’s independence. All hope with me in Irish affairs is dead and buried. I have ever esteemed you at once the honestest and most gifted of my country-men and your departure from Ireland leaves me no hope.” In 1879, clean on a quarter of a century after that despairing letter had been written, Mr Parnell went down to the little market town of Thurles, in Tipperary, where Dr Croke resided, to request the Archbishop to give his support to the Land League agitation which had just been inaugurated. Dr Croke stated some years afterwards that he was at first reluctant to join the movement and that he only yielded his consent when Mr Parnell actually went on his knees before him, saying, “I must have the Bishops at the head of this movement, else it will not succeed.” However, Dr Croke soon became the most active Land Leaguer among the Roman Catholic hierarchy. He supported the agitation in vigorous letters and speeches. But he thought the no- rent manifesto, issued on the proclamation of the Land League by Mr W. E. Forster, in 1881, was going too far. He wrote an address to the people of Ireland denouncing it, not, indeed, so much because it was immoral, as because it was illogical. He said that the trim reply to the proclamation of the Land League was to refuse to pay taxes rather than to repudiate debts due to a number of individuals, who had no responsibility for the action of the Government. Two years later he sent another letter to the Press advocating a national testimonial to Mr Parnell for his services to Ireland. Pope Leo XIII issued an encyclical letter condemning the tribute, but this had the effect of increasing the subscription, and ultimately Mr Parnell was presented with a cheque for £40,000. Dr Croke and a number of other Bishops were summoned to Rome to explain their conduct to the Holy See. When he returned he received a most enthusiastic welcome, and in a speech at a public meeting declared he was “unchanged and unchangeable.”

In 1890 it fell to the lot of Dr Croke to draw up, on behalf of the Roman Catholic hierarchy of Ireland, an address to the Irish people declaring that Mr Parnell was not a fit man to be their leader, because of the disclosures of the O’Shea divorce case. This address was not issued until after the publication of Mr Gladstone’s letter stating that his efforts on behalf of Home Rule would be fruitless if Mr Parnell were retained as chairman of the Irish party. The charge was subsequently made against the hierarchy that they had postponed taking action until they saw how things were going decisively, but Dr Croke explained, five years later, that the delay was due entirely to the fact that the document had to be sent to Bishop after Bishop for signature. After the fall of Mr Parnell Dr Croke retired from public life. Appeals were frequently made to him to try to settle the differences between Parnellites and anti-Parnellites, O’Brienites and Healyites, but he refused absolutely to intervene.

Dr Croke, physically, was over 6ft. high and well made in proportion. In his youth and early manhood he had been a champion athlete in leaping and jumping, and was distinguished also in the hurling and football fields. All through life he took the keenest interest in the national sports and pastimes of the Irish people. On the foundation of the Gaelic Athletic Association in 1885 for the revival of Irish games he became its president. In his address on the subject he said:-

“Ball playing, hurling, football kicking, according to Irish rules, ‘casting’ (or throwing the stone), leaping in various ways, wrestling, handy-grips, top-pegging, leap-frog, rounders, tip-in-the-hat, and all such favourite exercises and amusements amongst men and boys may now be said to be not only dead and buried, but in several localities to be entirely forgotten and unknown. And what have we got in their stead? We have got such foreign and fantastic field sports as lawn tennis, polo, croquet, cricket and the like. Very excellent, I believe, and health-giving exercises in their way, still not racy of the soil, but rather alien to it.”

There might be, he added, “something rather pleasing to the eye in the get-up of the modern young man who, arrayed in light attire, with party-coloured cap on, and racket in hand, is making his way, with or without a companion, to the tennis ground,” but he preferred the youthful athletes of his early years – “bereft of shoes and coat and thus prepared to play at hand-ball, to fly over any number of horses, to throw the sledge of winding-stone, and to test each other’s mettle and activity by the trying ordeal of three leaps, or a hop, step, and jump.”

Dr Croke was of a genial and warm-hearted nature. He delighted in hospitality at his palace in Thurles, and after dinner was fond of regaling his guests with humorous Irish stories and Irish comic songs. He had a contempt for books, but especially abhorred collections of sermons. He did not hesitate to declare that Irish history was too cheerless a chronicle for him to study. It was infinitely better, he also said, to try to make history, even in a small way, than to write volumes about it.

* * *

MICHAEL DAVITT

31 MAY 1906

MR MICHAEL DAVITT died early this morning at a private hospital, in Lower Mount-street, Dublin, where he had been lying in a critical condition for some days. Michael Davitt, probably the most resolute and implacable enemy of the connexion between Great Britain and Ireland that has appeared in modern time, was born at Straid, a small village in county Mayo, in March, 1846, a few weeks before the birth of Charles Stewart Parnell, his associate in after life, though coming from a very different social stratum. Davitt’s father was a petty peasant farmer, who was evicted in 1851 for non-payment of rent, which, however, it is alleged, had not been raised during the period of his tenancy. The family then migrated to Lancashire, and settled in the small manufacturing town of Haslingden, where the boy found employment in a cotton mill, and, though a Roman Catholic, got his elementary education at a Wesleyan school. When he was 11 years old a machinery accident deprived him of his right arm, but he got casual occupation as a newsboy, as an assistant letter-carrier, and ultimately as an employé in a small printing office. Reading widely if not wisely, he drifted rapidly into the ranks of the Fenian Brotherhood, which became actively aggressive in 1865. When an abortive attempt was made by the Fenians to capture Chester Castle, early in 1867, Davitt, according to an admiring biographer, “though unable to shoulder a rifle with his single arm, carried a small store of cartridges in a bag made from a pocket-handkerchief.” When the baffled band of conspirators broke up, Davitt escaped detection and returned to Haslingden, where he immediately resumed “active operations,” arranging for the secret export of firearms to Ireland. This led to his arrest in 31 May, 1870, on a charge of “treason felony,” on which he was tried at the Old Bailey, with a confederate, before Lord Chief Justice Cockburn, and convicted, without hesitation, by the jury. A letter in Davitt’s handwriting was produced and sworn to, a passage in which, the Chief Justice said, in passing a sentence of 15 years’ penal servitude, showed that there was “some dark and dangerous design against the life of some man.” Towards the close of 1877, however, Davitt was released, after serving half of his sentence in Dartmoor Convict Prison, and a few months later he visited the United States, where his mother, herself of American birth, though of Irish blood, had settled with other members of the family. Before crossing the Atlantic he had rejoined the “Irish Republican Brotherhood,” the branch of the Fenian organization established in Ireland, and was elected a member of the “Supreme Council,” which practically admitted him to confidential relations, as the Special Commission found, with the Clan-na-Gael and the whole body of American-Irish Fenians. He told the Commissioners himself that he had “a well-defined purpose” in visiting the States, which, as his further evidence showed, was to “make the Land Question the stepping-stone to national independence.” With another Fenian and ex-convict, John Devoy, Davitt, during his stay in America, studied the methods of revolution through agrarian agitation devised 30 years before by Fintan Lalor, and on his return to Ireland the confederates launched the “new departure,” with the assent and co-operation of the emissaries of the Clan-na-Gael, the aim being to combine the physical force faction and the agrarian revolutionists in a common policy, embracing an attack on rents and the acquisition of complete control over local elected bodies. Into this policy Mr Parnell was gradually drawn, and the Land League, originally started at Irishtown, in Mayo, early in 1879, developed, half a year later, into a “national organization,” with its seat in Dublin, Parnell as president, and Davitt as one of the secretaries. In view of the anti-clerical developments of Davitt’s later career, it is worthy of notice that the Irishtown meeting was called to denounce a landlord who was also a parish priest, one Canon Burke. Parnell’s visit to America, his violent speeches there, the assurances given to the physical force party that their methods were not to be interfered with were among the first results of the foundation of the Land League. Davitt himself crossed the Atlantic in May, 1880, just after the general election, and for several months acted “as the link between the two wings of the Irish party,” explaining to the Fenians that the aims of the two sections did not clash and that they might be of mutual aid to one another.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.