Полная версия

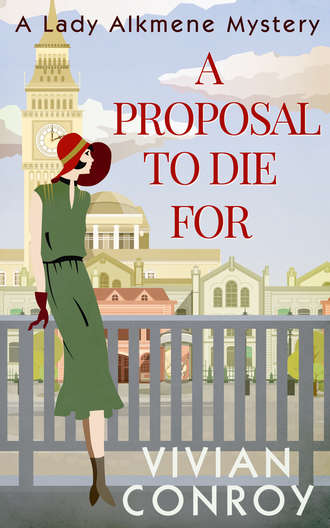

A Proposal to Die For

A murderous beginning

With her father away in India, Lady Alkmene Callender finds being left to her own devices in London intolerably dull, until the glamorous Broadway star Evelyn Steinbeck arrives in town! Gossip abounds about the New York socialite, but when Ms Steinbeck’s wealthy uncle, Silas Norwhich, is found dead Lady Alkmene finds her interest is piqued. Because this death sounds a lot to her like murder…

Desperate to uncover the truth, Lady Alkmene begins to look into Ms Steinbeck’s past – only to be hampered by the arrival of journalist Jake Dubois – who believes she is merely an amateur lady-detective meddling in matters she knows nothing about!

But Lady Alkmene refuses to be deterred from the case and together they dig deeper, only to discover that some secrets should never come to light…

The twenties have never been so dangerous…

Available from Vivian Conroy

A Lady Alkmene Callender Mystery series

A Proposal to Die For

Diamonds of Death

Deadly Treasures

A PROPOSAL TO DIE FOR

Vivian Conroy

www.CarinaUK.com

VIVIAN CONROY

discovered Agatha Christie at thirteen and quickly devoured all the Poirot and Miss Marple stories. Over time Lord Peter Wimsey and Brother Cadfael joined her favourite sleuths. Even more fun than reading was thinking up her own fog-filled alleys, missing heirs and priceless artefacts. So Vivian created feisty Lady Alkmene and enigmatic reporter Jake Dubois sleuthing in 1920s’ London and the countryside, first appearing in A Proposal to Die For. For the latest on #LadyAlkmene, with a dash of dogs and chocolate, follow Vivian on Twitter via @VivWrites

Thanks to all editors, agents and authors who share insights into the writing and publishing process.

A special thanks to my fantastic editor at Carina UK/HarperCollins Victoria Oundjian, for loving Lady Alkmene from the first chapter of A Proposal to Die For – read off Carina’s Will You Marry Me? special call – and to the design team for the amazing cover that reflects the era so well.

Note

Writing mysteries set in the 1920s, I’m grateful for all online information – think dress, transportation, etiquette and much more – to ensure an authentic period feel. Still, Lady Alkmene’s world remains fictional, including street addresses, establishments and even entire villages of my invention.

Contents

Cover

Blurb

Book List

Title Page

Author Bio

Acknowledgements

Note

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Excerpt

Endpages

Copyright

Chapter One

‘Marry me.’

The whispered words reached Lady Alkmene Callender’s ears just as she was reaching for the gold lighter on the mantelpiece to relight the cigarette in her ivory holder.

Freddie used to be a dear and bring her Turkish ones, but since he had been disinherited by his father for his gambling debts, his opportunities to travel had been significantly reduced, as had Alkmene’s stash of cigarettes. These ones, obtained from a tobacconist on Callenburg Square, had the taste of propriety about them that made them decidedly less appetizing than the exotic ones she had to hide from her housekeeper – who always complained the lace curtains got yellowish from the smoke.

‘Marry me,’ the insistent voice repeated, and Alkmene’s gaze wandered from the mirror over the mantelpiece to the table with drinks beside it.

Behind that table was a screen of Chinese silk, decorated with tiny figures tiptoeing over bridges between temples and blossoming cherry trees.

The voice seemed to emerge from behind the screen.

Another voice replied, in an almost callous tone, ‘You know I cannot. The old man would die of apoplexy.’

‘Not that he doesn’t deserve it. If he died, you’d inherit his entire fortune and we could elope.’

‘Where to?’

‘Gretna Green, I suppose. Where else does one elope to?’

Alkmene decided on the spot that the male speaker had a lack of fantasy, which would make him unsuitable for her adventurous mind. If you did elope, you’d better do it the right way, boarding the Orient Express.

‘I mean,’ the female said, in an impatient tone, ‘where would we live, how would we live? Off my fortune I suppose? I don’t think the major would give me a dime.’

‘What has the major got to do with it? Once the old man is dead and we are married, the money is yours.’

There was a particular interest in money in this young man’s approach that was disconcerting, Alkmene decided, but if the female on the other side of the Chinese silk didn’t notice or care, it was none of her business.

‘Alkmene, dushka…’

Alkmene turned on her heel to find the countess of Veveine smiling up at her from under too much make-up. The tiny Russian princess, who had married down to be with the love of her life, wore a striking dark green gown with a waterfall of diamonds around her neck. Matching earrings almost hung to her shoulders, and a tiara graced her silver hair. ‘I had expected to see you at the theatre last week. Everybody who is somebody was there.’

‘I was…’ reading up on the fastest-working exotic poisons ‘…detained unfortunately. But I trust you had a pleasant night?’

‘The new baritone from Greece was a revelation.’ The tiny woman winked. ‘You should meet him some time. Just the right height for you. Never marry a man who is shorter. You will always have to look down on him, and it is never wise to marry a man on whom one must look down.’

Alkmene returned her smile. ‘I will remember that.’

She heard a light scratch of wood and turned her head to see a young woman adjusting the Chinese screen. She wore a bright blue dress and matching diadem, her platinum blonde hair shining under the light of the chandelier.

She looked up and caught Alkmene’s eye. ‘The thing always tips over to the side. Would crash the table and destroy all of those marvellous crystal glasses.’

She had a heavy American accent, but Alkmene recognized her voice anyway. It was the woman who had moments ago been discussing her marital prospects and a possible elopement with a man behind the screen. Her accent had been a lot less obvious then. But her reference to the major not giving her ‘a dime’ did suggest she was American.

Intrigued, Alkmene came over and said, ‘Let me give you a hand with that. It is huge.’

She glanced behind the screen, but there was nothing to be seen. Nobody – hardly room enough for two persons to stand. If she wasn’t perfectly sure she had heard the conspiring voices, she’d have deemed it impossible.

She pretended to test the screen’s stability by grabbing the top and pulling at it. ‘It seems solid enough to me.’

The young lady smiled at her. ‘Why, thank you, much obliged. A drink perhaps?’ She had already gestured to a waiter to bring them fresh glasses of champagne.

Outside a car horn honked, and someone lifted the curtain to look out and see who was arriving so late to the party. Alkmene didn’t have to look to know. Self-made millionaire Buck Seaton liked to be noticed wherever he arrived. No doubt upon his entrance he’d be hollering about a terrible traffic jam in Piccadilly, to make sure he could spend the next hour talking about his new automobile. It would probably be American, like this young lady by her side.

As the blonde handed her a glass of bubbles, Alkmene said, ‘How do you like London? Have you been here long?’

‘Just a few weeks.’ The blonde took a sip of her champagne, careful not to smudge her bright red lipstick. The colour might be cheap on another, but with her it underlined her stark classic beauty. As of a silver screen icon.

Alkmene said, ‘There is a wonderful exhibition right now in a renowned art gallery on Regent Street.’

‘I’ve already been there,’ the blonde said with a weak smile. ‘My uncle is an admirer of art. Sculptures, paintings. He even said he might hire someone to have my portrait done. A bit old-fashioned if you ask me. I’d rather have him hire me a star photographer. In the time I’d have to sit still for a portrait he could have taken my picture a hundred times. And not in front of some dull old bookcase either, but balancing on the railing of London Bridge.’

At Alkmene’s stunned expression the other woman burst into heartfelt laughter.

There was commotion at the door as Buck Seaton emerged, still wearing the preposterous goggles he always used when driving an open automobile. Pulling them off, he stretched his already impressive height to look around the room and spotted the blonde. ‘Evelyn!’ He waved the goggles in the air.

The blonde’s face lit at once, and she took a hurried leave, readjusting her long gloves as she made her way over to the millionaire. He leaned over confidently, kissing her on the cheek and speaking to her in an urgent manner.

‘I saw her last week at the theatre,’ the countess said in a pensive tone. ‘She was with a much older man.’

‘Must be the uncle she just mentioned to me,’ Alkmene said. ‘The art lover. You did not know him?’

The countess shook her head. ‘He has never been introduced to me. I actually thought they must both have been new to London for I had never seen either of them before and I do see people everywhere, you know. It was very odd. They came when the performance had already begun and they left during the break.’

‘Maybe they just didn’t like the singing,’ Alkmene concluded.

The countess shook her head. ‘It was not the performance. I think there was an argument in their box. A young man arrived, and there was a heated discussion.’

Ah. The countess had been training her opera glasses on the other boxes instead of on the stage. Alkmene also found it difficult to concentrate on sung love triangles for long stretches, even if the baritone was a tall dark Greek. ‘This young man, can he have been her fiancé or something?’ She was still curious about the man who had been with the blonde behind the Chinese screen just now.

Elopement rather suggested the relationship was illicit, but who knew, he might be a long-suffering fiancé who finally wanted to marry the girl and be done with it.

The countess’s fine brows drew together in concentration. ‘I do not think so. The old man seemed very surprised to see him – and upset. I think almost…startled. Like he had seen a man returned from the dead.’

Alkmene hitched a brow. ‘Returned from the dead? You mean, like he didn’t want to meet him?’

‘No, literally.’ The countess waved a breakable hand covered with a thin web of green veins. ‘Like he had seen someone whom he believed to be dead and all of a sudden he was there, in his life again. Making demands on him.’

Alkmene pursed her lips. ‘That sounds rather intriguing. I wish I had been there, and could have seen them for myself.’ Their gestures during the argument, or just the clothes of the unexpected arrival, could have told her so much. Leaning over eagerly, she asked, ‘This man returned from the dead, was he a gentleman, well dressed, in place there, or rather different? A foreigner perhaps?’

‘He was young, tall, broad in the shoulders. Well dressed, but not rich, if you know what I mean. Not like all of those sons of earls and dukes, running about.’

The countess sounded so deprecating that Alkmene had to laugh. ‘They are not all bad, you know.’

The countess waved a hand. ‘Ah, but they have never had to work for anything, long for anything, strive for it with all of their energy. They have it all; they get things with a flick of the hand. It doesn’t make men of them. Oh…’ She suddenly focused across the room and said, waving past Alkmene, ‘There is a dear friend I must see. Take care. Greet your father from me.’

Alkmene did not take the trouble to explain her father was off again on one of his botanical quests, this time to India, and was not expected to be back before Michaelmas.

The idea of all those weeks of delicious luxurious freedom beckoned her, and with a smile she reached for another glass of champagne.

Two days later, over toast with Cook’s excellent prune preserve, Alkmene unfolded the morning paper, still pristine as her father was not there to smudge it with egg yolk and bacon grease while he studied the social column so he could send attentions for weddings and births and always appear to be an engaged gentleman instead of a hermit who only knew the Latin names of plants.

He was so good at hiding his social deficiencies that people kept sending him invitations to balls and soirées he had stopped attending two decades ago. In his defence it had to be said that Alkmene usually pinched the envelopes from out between his other letters as soon as the post came in. Her father was a dear but a disaster in the wild, and he preferred the company of his microscope and his mould specimens anyway.

On page 2 a heading read: Banker dies in accident.

Unexpected death always had an unhealthy appeal to Alkmene, and she perused the few lines underneath with great interest.

‘Yesterday morning around eight Mr Silas Norwhich, a former banker, was discovered dead by his manservant in his library, apparently having fallen and struck his head on the rim of the hearth the night before. As it had been the servants’ night off, nobody had noticed the incident until the next morning.

‘A widower with no children, Mr Norwhich lived a very secluded life, focusing solely on his substantial art collection. The collection, containing masterpieces from Rembrandt, Van Gogh, Monet and Rodin, will now pass to his only heir: his niece, the actress Evelyn Steinbeck, recently come in from New York City, where she is a rising star on Broadway.

‘Miss Steinbeck wasn’t home at the time of the accident and has been treated by a doctor for nervous shock.’

It was rather a short and poor piece, lacking any form of useful information about the death, but Alkmene forgot the prune preserve and studied the text as if it contained the vital clues to the whereabouts of a gold mine.Buck Seaton had called the young woman who had appeared from behind the screen the other night Evelyn. She had spoken with an American accent and admitted she had only been in London for a few weeks. She had also mentioned an uncle who was an art lover.

The countess, who had seen the blonde at the theatre, had mentioned her being there with an older man who was not known to her socially, which fit with the newspaper’s assertion that the murdered man had lived a very secluded life.

Apparently until his vivacious niece from New York had arrived.

He had wanted to have her portrait painted and had taken her out to the theatre.

Not that Evelyn Steinbeck seemed to have appreciated the trouble her uncle took for her. She had spurned the portrait in favour of photographs.

Of her balancing on the railing of London Bridge no less. A testimony to a daring character, taking risks rather than fitting the mould.

And her talk of the old man and him dying of apoplexy behind the screen had been callous, almost cruel. Like she wanted to get rid of excess weight.

Alkmene stared into the distance. Evelyn had discussed her uncle’s death with a man, and lo and behold, two days later he was dead and she would inherit his art collection. Judging by the mention of some of the pieces it contained, it had to be worth a fortune. An excellent motive for murder.

But what about the young intruder into the theatre who had given the old man such a fright? The argument between them had been the cause for the old man to leave the performance early. Out of fear?

Had the intruder followed him to see where he lived? Killed him when he had been alone? It had been the servants’ night off so if somebody had rung the bell, the old man would have answered the door himself.

Alkmene narrowed her eyes. A push, a fall and no one around to see a thing…

With a beautiful, manipulative heiress and an intimidating stranger part of this story, there had to be something more behind the ‘accidental’ death. It warranted further investigation.

She left her breakfast for what it was, already shrugging out of her purple embroidered dressing gown while still climbing the stairs.

There was no place like the Waldeck tea room to catch some gossip about a sudden death.

Chapter Two

Alkmene entered the Waldeck tea room through the double doors with elaborate glass-in-lead overhead. The sunshine piercing the coloured glass conjured up a mosaic of rainbows on the wall above the counter filled with pastries. Customers ordered their pie of choice there and carried it to their table where a waiter served them with tea or coffee from delicate china cups decorated with the tea room’s trademark roses.

As Alkmene let her eye wander across the mouth-watering offerings, her ears picked up on the light laughter of the countess of Veveine.

The Russian princess visited the tea room every day but Sundays, taking a seat by the window where she could watch people go by and putting her order on her ever-growing bill.

With the money she could spend, she could have several pies, but she always took the pavlova, a special creation by the French chef Maurice.

Alkmene wasn’t entirely sure if the pavlova was that good, or Maurice would be mortally insulted if the countess didn’t order it. As a typical chef with a fierce pride in what he did, he didn’t allow anybody to slight his creations and it was whispered he had even refused to do a big banquet at an earl’s New Year’s party after the earl’s wife had made a comment about his mayonnaise.

‘I’ll have the Schwarzwälder Kirsch.’ Alkmene smiled at the young woman behind the counter who ably manoeuvred a gleaming steel spatula underneath the largest piece and transferred it onto a plate.

Carrying the masterpiece carefully down the two steps leading into the tea room’s main room, Alkmene pretended to be engrossed and unaware of the countess’s presence. In reality she was sure the woman had already seen her come in and would call out to her the moment she put her foot on the black-and-white inlaid floor.

But nothing happened.

Surprised, Alkmene glanced at the window table, seeing the countess, in a deep purple gown with matching stones in her necklace and bracelet, sitting and leaning over to a handsome man with a shock of black hair, rather too long to be decent.

The countess’s companion, an elderly woman who never stopped knitting, sat over her work, head down, needles clicking furiously, her demure fervour a silent reproach against her mistress’s behaviour.

Alkmene had to agree the countess’s cheeks were suspiciously red and her laughter was high-pitched with excitement.

The man looked up from the countess, straight at Alkmene. He had dark, probing eyes in a face exposed to rather too much sunshine. His suit was an unobtrusive dark blue, but the sunshine sparkled on the gold cuff links. Alkmene bet his shoes would turn out to be handmade, of the finest leather.

A man who liked to treat himself.

A self-made millionaire like Buck Seaton perhaps, looking for titled friends to add the lustre of old names to the shine of his fortune. People like him would buy their way into the peerage if they could.

Always reluctant to be used to any purpose, Alkmene put her plate down on an empty table and took the time to strip off her immaculate gloves. Keeping her back straight the way her nanny had told her a thousand times, she scanned the other side of the room for an acquaintance who might enlighten her about Mr Silas Norwhich’s unfortunate ‘accident’.

After all, that was what she was here for.

But already there were light footfalls behind her, and the countess’s companion put a hand on her arm. ‘Come,’ she said in such a heavy accent that the word was almost unrecognizable. ‘Come!’

Alkmene picked up the plate again and followed the scurrying figure to the countess’s table.

The waiter who had just appeared to take her order came dutifully along, staying one pace behind her.

The countess waved at him. ‘More tea for all of us. Sit down, Alkmene. We were just having the most interesting conversation. This young man is telling me everything about the terrible disaster with the SS Athena.’

Alkmene shot him a quick glance as she seated herself. She had only read about the disaster, but the account had raised a number of pertinent questions in her mind.

Especially about the part played by those members of the crew who had survived while so many of the passengers had not.

She asked, ‘You were on the ship when it sank?’

He shook his head. ‘I have been talking to survivors.’

The countess leaned over. ‘Did you know that there have been rumours the captain survived because he fled, while he should have stayed in his place? It is terrible that people have no sense of integrity any more. In the old days people would rather have died in the armour, as you English say, than live on having run away.’

‘I suppose one does odd things when one looks death in the eye,’ the man said.

He studied Alkmene with a critical intensity that made her wince. She hadn’t put on her best clothes because she had not been sure where her quest would take her. If it should be to the lunchroom where secretaries and the like had their lunches, she wanted to blend in, not stand out like a spoiled rich lady who had mistaken the establishment. It was exciting to go undercover, play somebody else, somebody astute and able, who was not forever invited for her family name.

But for this man her clothes didn’t appear to be rich enough for Waldeck’s.

He probably didn’t consider her worth his time, if he was here to hunt for loaded ladies who felt flattered by the attentions of a much younger man.

Admittedly, the countess was married and would never be unfaithful to the love of her life, but she might give this young man some money if he told her in deep earnest about something he wanted, a dream he had already worked hard for.

Last summer one of Father’s countryside acquaintances had found out that his sister had lent a substantial sum of money to a smooth-talking young man who had found a gold mine in Africa and only needed the money to mine it. Needless to say, he had vanished with the money – never to be heard of again.

The gullible woman had been so mortified she had left her gossiping friends behind for a stay with a friend in Rome. Alkmene agreed with her that if you had to rethink your own stupidity, it could best be done in the Mediterranean sun.

The waiter brought a cup for her and filled it with a deliciously aromatic tea. Alkmene detected a hint of lavender and some other sweet fragrance she couldn’t quite identify. She wanted to ask about it, determined to buy it for her own collection at home, but the countess forestalled her by placing a delicate hand on Alkmene’s arm, while saying to the well-dressed man, in a conspiratorial tone, ‘Mr Dubois, you must tell Alkmene what you have discovered so far.’