Полная версия

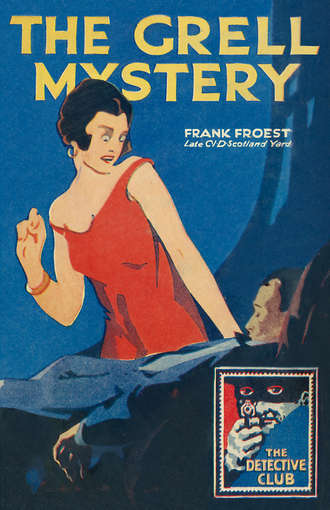

The Grell Mystery

‘I have come to apologise for my rudeness at Grosvenor Gardens,’ he began. ‘I was worried, and you were, of course, upset. Now we are both more calm, I come to ask you if you would like to add anything to what you said. Of course, you’ll be called to give evidence at the inquest, and it would make it easier for you as well as for us if we knew what you were going to say.’

Fairfield shrugged his shoulders. ‘I have told you all you will learn from me,’ he said quickly. ‘I suppose you’ve seen Lady Eileen Meredith.’

‘No.’ The lie was prompt, but the superintendent salved his conscience with the thought that it was a necessary one. ‘I don’t know that she can tell us anything of value.’

An expression of relief flitted over the face of Grell’s friend. After all, it was something to have the worst postponed. A man may face swift danger with debonair courage, may be undaunted by perils or emergencies of sport, of travel, of everyday life. But few innocent men can believe that a net is slowly closing round them which will end in the obloquy of the Central Criminal Court, or in a shameful death, without feeling something of the terror of the hunted. ‘The terror of the law’ is very real in such cases. Fairfield was no coward, but his nerves had begun to go under the strain of the suspense. It would have been different had he been able to do anything—to find relief in action. But he had to remain passively impotent.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘I expect you’re very busy, Mr Foyle. I don’t want to keep you.’

The detective received the snub with an amiable smile. ‘I won’t force my company on you, Sir Ralph. If you will just dictate to me a description of the string of pearls that Grell showed you, I will go. Can you let me have a pen and some paper?’

Ungraciously enough Fairfield flung open a small inlaid writing-desk, and Foyle took down the description as though he really needed it. As he finished he held out the pen to Fairfield.

‘Will you sign that, please? No, here.’

Their hands were almost touching. Foyle half rose and stumbled clumsily, clutching the other’s wrist to save himself. The baronet’s hand and fingers were pressed down heavily on the still wet writing. The detective recovered his balance and apologised profusely, at the same time picking up the sheet of paper.

‘I don’t know how I came to do that. I am very sorry. It’s smudged the paper a bit, but that won’t matter. It’s still readable. Good-bye, Sir Ralph.’

So admirably had the accident been contrived that even Fairfield never suspected that it was anything but genuine. In a public telephone-box, a few hundred yards away, Heldon Foyle was examining the half-sheet of notepaper side by side with the photograph of the finger-prints on the dagger. A telephone-box is admirably constructed for the private examination of documents if one’s back is towards the door and one is bent over the directory. Line by line Foyle traced ‘laterals,’ ‘lakes,’ and ‘accidentals,’ calling to his aid a magnifying glass from his waistcoat pocket.

When he emerged he was rubbing his chin vigorously. The prints were totally different. Sir Ralph Fairfield was not the murderer of the man so astoundingly like Robert Grell.

CHAPTER X

THE evidence of the finger-prints was entirely negative. Though Foyle believed that Fairfield was innocent, he never permitted himself to be swayed by his opinions into neglecting a possibility. It was still possible that the baronet might have been concerned in the crime even though they were someone else’s prints on the dagger. At any rate Fairfield was suppressing something. It could do no harm to continue the watch that had been set upon him. So Foyle left Green and his companion to continue their unobtrusive vigil.

To justify his stay in the box—for he was artist enough to do things thoroughly even though it might be unnecessary—he lifted the receiver and put a call through to Scotland Yard.

‘This is Foyle speaking,’ he said when at last he had got the man he asked for. ‘Is there anything fresh for me?’

‘Nothing important, sir, except that Blake has found a curiosity dealer who says that the knife is one that must have come from South America. It is, he says, an unusual sort of Mexican dagger.’

‘Oh. Is the man who says that to be relied on? He isn’t just guessing? We can do all the guessing we want ourselves.’

‘No, sir, we think he’s all right. It’s Marfield—one of the biggest men in the trade. By the way, sir, there’s a lot of newspaper men been asking for you since you left. They want to know about Goldenburg.’

‘So do I,’ retorted the other. ‘You’d better be strictly truthful with ’em, Mainland. Tell ’em you know no more than is on the reward bill. They won’t believe you, anyway. You can say I’ve gone home to bed, and that there will be nothing more doing this evening. Good-bye.’

‘A Mexican dagger,’ he muttered to himself as he left the telephone-box. ‘Now, if I were a story-book detective I should assume that the murderer was either a South American or had travelled in South America. It looked the kind of thing a woman might carry in her garter. And a veiled woman called on him that night’—he made a wry face. ‘Foyle, my lad, you’re assuming things. That way madness lies. The dagger might have been bought anywhere as a curiosity, and the veiled woman may have been a purely innocent caller.’

His meditations had brought him to a great restaurant off the Strand. He passed through the swing doors into the lavishly gilded dining-room, and selected a table somewhere near the centre. With the air of a man taking his ease after a strenuous day in the City, he ordered his dinner carefully, seeking the waiter’s advice now and again. Then his eye roved carelessly over the throng of diners while he waited for his orders to be fulfilled. The apparently casual scrutiny lasted rather less than a minute. Then he shifted his seat so that he could see without effort the table where two men lingered over their liqueurs. A moment later one of the men noted the solitary figure of the detective.

He emptied his glass without haste and signalled to the waiter. Before that functionary had made out the bill Foyle had strolled over to the table, his face beaming, his hand outstretched.

‘How are you, Eden?’ he cried effusively. ‘Who’d have thought of seeing you here! Business good? Still picking flowers?’

An expression of annoyance crossed the face of the slighter built of the two men, yet he shook hands readily.

‘Why, it’s Mr Foyle!’ he exclaimed heartily. ‘How are you? We were just going. Let me introduce Mr Maxwell.’

They called him the Garden of Eden at Scotland Yard—probably because the unwary might have thought him full of innocence. His smooth, bronzed boyish face showed ingenuousness and candour in every line. A glittering diamond pin adorned his necktie, a massive gold chain spanned his waistcoat, a gold ring with a single great ruby was on his finger. That was the only ostentation about him, and his quiet, well-cut clothes were in good taste.

Foyle acknowledged the introduction.

‘From the colonies, I suppose, Mr Maxwell? I suppose Eden has told you he’s just come over.’ Eden surveyed the detective with wide-open, innocent blue eyes in which there dwelt hurt reproach. ‘I hate to separate you, but I’ve got important business with him. Perhaps you’ll meet another time.’

‘Yes, you’ll excuse me now, old man,’ chimed in Eden blandly. ‘Call for me at the Palatial at eleven tomorrow, and we’ll make a day of it.’

Maxwell had no sooner accepted his dismissal than Foyle led the other over to his table. Eden walked with the manner of one uncertain what was about to happen.

‘It is all right, Mr Foyle,’ he protested eagerly. ‘It is all right. I haven’t touched him for a sou.’

Foyle began on the soup placidly.

‘You’re a joker, Jimmy,’ he smiled. ‘Don’t get uneasy. I’m not going to carry you inside. Only you’ll have to leave the Palatial tonight, Jimmy—tonight, do you understand? And if Maxwell turns up with a complaint against you there’ll be pretty bad trouble. You’ll be put out of temptation for good and all. There’s such a thing as preventive detention in this country now, you know.’

The Garden of Eden looked pained.

‘Truth, Mr Foyle, I haven’t done a thing,’ he declared earnestly. ‘I’m trying the straight game now.’

Heldon Foyle wagged his head.

‘And staying at the Palatial,’ he smiled. ‘Oh, Jimmy, Jimmy! I believe you, of course.’ And he went on with his soup.

Suddenly he looked up. ‘When did you last see Goldenburg?’ he demanded curtly. ‘No nonsense, mind, Jimmy.’

Eden’s face had cleared. ‘So that’s the lay, is it?’ he said with relief. ‘I saw the bills out for him, and I don’t mind helping you if I can, Mr Foyle. He was never what you’d call a proper pal, and I don’t bear any malice, though you’ve just done me out of a cool five hundred. That mug who’s just gone’—he jerked his head towards the door—‘was going to follow my tip and back a horse that won’t win tomorrow. That’s a bit hard, isn’t it, Mr Foyle?’

From his breast-pocket Foyle took a ten-pound note and slid it across the table. He followed Eden’s meaning.

‘Cough it up,’ he advised.

The Garden of Eden took the note and thrust it into his trousers pocket.

‘He was in Victoria Station, talking to a foreign-looking chap, on Wednesday night.’ A look of astonishment crossed his face while he spoke. ‘By the living jingo, there’s the very man he was talking to coming in now.’

Foyle folded his serviette neatly and rose.

‘Right, Jimmy. I’ll talk to you later. Go to the Yard and wait till I come,’ he said, and, walking swiftly across the room, thrust his arm through that of the new arrival.

‘You are the man who used to be Mr Grell’s valet,’ he said quietly in French. ‘I am a police officer, and you must come with me.’

CHAPTER XI

THE man tried to jerk himself free, but the detective’s fingers closed tightly about his wrist.

‘There is no use making a scene, my man,’ he said, still speaking in French, his voice stern, but pitched in a low key. ‘You are Ivan something-or-other, and you know of the murder of your master. So come along.’

‘It’s a mistake,’ protested the other volubly in the same language. His words slurred into each other in his excitement. ‘I am not the man you take me for. I am Pierre Bazarre, a jeweller of Paris, and I have my credentials. I will not submit to this abominable outrage. I know nothing of M. Grell; you shall not arrest me—’

Heldon Foyle cut him short. He had, without the appearance of force, quietly forced his prisoner outside the restaurant and signalled to a passing taxicab.

‘I am not arresting you,’ he said, ignoring the protestations of the other. ‘I am going to detain you till you give a satisfactory explanation of your reason for leaving Mr Grell’s house on the night of the murder.’

They were on the edge of the pavement close to the cab. Ivan with a quick oath wheeled inward, and struck savagely at the superintendent’s face. Foyle’s grip did not relax. He merely lowered his head, seemingly without haste, and, as the man swung forward with the momentum of the blow, jabbed with his own free hand at his body. So neatly was it done that passers-by saw nothing but an apparently drunken man collapse on the pavement in spite of the endeavours of his friend to hold him up.

The whole breath had been knocked out of Ivan’s body by those two swift body-blows. Before he could recover, Foyle had lifted him bodily into the cab.

‘King Street,’ he said quietly to the driver, and sat down opposite to Ivan, alert and watchful.

‘Sorry if I hurt you,’ he apologised. ‘It will be all right in a minute. It has only upset your wind a little. That will pass off.’

Ivan, his hands pressed tightly to the pit of his stomach, groaned. Presently he straightened himself up, and Foyle, calmly ignoring the assault, produced a cigar-case.

‘Have a cigar? I’ve no doubt you’ll be able to make things all right when we get to the station. There’s nothing to worry about. You will just have a little talk with me, and as soon as one or two points are cleared up you’ll be able to go.’

The case was struck angrily aside. Foyle smiled, and although his whole body was taut in anticipation of any fresh attempt at violence, he quietly struck a match and lit one himself.

‘As you like,’ he said imperturbably. ‘They’re good cigars. I have them sent over to me by a friend direct from Havana.’

All the while he was speaking he was scrutinising the man who had been Grell’s valet with deliberate care. Ivan was sleek and well-groomed, with a dark face and prominent cheekbones that betrayed his Caucasian origin. The brows were drawn tightly in a surly frown; a heavy dark moustache hid the upper lip, and though the shoulders were sloping he was obviously a man of considerable physical strength.

Foyle felt that it was going to be no easy matter to win this man’s confidence. Yet he was determined to do so. Beyond the fact that he had vanished when the murder was discovered, there was nothing so far to suggest that he was the actual culprit. Certain it was, however, that he must have knowledge of matters which would prove valuable. If he would volunteer the information, well and good. The detective did not wish to have to question him, for such a course, however advisable it might appear, could be made to assume an ugly look in the hands of the astute counsel, should the man be charged with the crime. Where by French or American methods a statement might have been extracted by bullying or by cross-examination, here it had to be extracted by diplomacy if possible.

Sullen and silent, Ivan alighted from the cab as it drew up under the blue lamp outside King Street police station. He passed arm-in-arm with Foyle up the steps. With a nod to the uniformed inspector in the outer office, the superintendent led him into the offices set apart for the divisional detachment of the Criminal Investigation Department. A broad-shouldered man with side whiskers, who was writing at a desk, looked up as they entered.

‘Good morning, Mr Norman,’ said Foyle. ‘This gentleman wants to tell me something about the Grell case. Just give him a chair, will you, and send in a shorthand writer who understands French to take a statement.’

‘I shall make no statement,’ broke in the Russian angrily, speaking in French, but with a readiness that showed he was able to follow English. ‘It’s all a mistake—a mistake for which you will pay heavily.’

‘Ah! that’s just what I wish to get at. There seems to be a little confusion. Perhaps I have been over-zealous, but the fact is, Monsieur—er—Bazarre, you are wearing a false moustache, and that rather aroused my suspicions—see?’

His hand did not seem to move, yet a second later the heavy moustache had been torn from the man’s face. He started to his feet with an exclamation. Foyle waved him back to his chair.

‘I only wanted to feel sure that I was right. Now, monsieur, I want to make it clear that I have no right to ask you anything. If you wish to say anything, it will be taken down, and what action I take depends on what you say.’

Ivan scowled into the fire and preserved a stubborn silence. Whether he knew it or not, he held all the advantage. Unless he committed himself by some incautious word, there was little to implicate him in the murder. Suspicion there might be, but legal proof there was none. It would scarcely do to arrest him on such flimsy evidence. The Russian police had failed to trace his antecedents, and the Criminal Investigation Department were ignorant even of his surname. He had been known simply as Ivan at Grosvenor Gardens.

Foyle tried again, and this time his voice was silky and soft as ever as he uttered a plainer threat.

‘I want to help you if I can. I don’t want to have to charge you with the murder of Mr Grell.’

The warm blood surged crimson to Ivan’s face. In an instant he was out of his chair and had leapt at the throat of the detective. So rapid, so unexpected was the movement that, although Heldon Foyle had not ceased his careful watchfulness, and although he writhed quickly aside, he was borne back by his assailant. The two crashed heavily to the floor. As they rolled over, struggling desperately, the grip upon the detective’s throat grew ever tighter and tighter.

Half a dozen men had rushed into the room at the noise of the struggle, and strove vainly to tear the Russian from his hold. But he hung on with the tenacity of a mastiff. There was a ringing in Foyle’s ear and a red blur before his eyes. With a superhuman effort he got his elbow under the Russian’s chin and pressed it back sharply.

The grip relaxed ever so slightly, but it was enough. Instantly Foyle had wrested himself free, and Ivan was pinioned to the floor by the others.

‘Handcuffs,’ said the superintendent sharply.

Someone got a pair on the prisoner’s wrists, and he was jerked none too gently to his feet. A couple of men still held him. At a word from Foyle the others had gone about their business, with the exception of Norman. The superintendent flicked the dust from his clothes, and picked something, which had fallen during the struggle, from the floor.

‘You admit you are Ivan, then?’ he said quietly.

The Russian showed his teeth in a beast-like snarl.

‘Yes, I am Ivan,’ he said. ‘Make what you can of that, but you cannot have me hanged for the murder of Mr Grell—and you know why.’

‘Because Mr Grell is not dead,’ retorted the detective smoothly. ‘Yes, I know that.’

He counted the rough-and-tumble but little against the fact that the Russian had now admitted that he knew it was not Grell’s body that had been found in the study. Here was a starting-point at last.

‘What I want now,’ he went on slowly, ‘is an explanation of how you came to have possession of these.’

He held up the thing he had picked from the floor. It was a case of blue Morocco leather, and as he opened it a magnificent string of pearls showed startlingly white against a dark background.

‘These pearls were bought at Streeters’ by Mr Grell as a wedding present to Lady Eileen Meredith,’ he said. ‘How do they come in your possession?’

‘They were given to me by Mr Grell,’ cried Ivan. The fierce passion that had made him attack Foyle on the hint of arrest seemed to have melted away.

Heldon Foyle’s mask of a face showed no sign of the incredulity he felt. He made no comment, but ran his hands swiftly through the Russian’s pockets, piling money, keys, watch, and other articles in a little heap on the table. Beyond a single letter there were no documents on the man. He scanned the missive quickly. It was an ordinary commonplace note from a jeweller in Paris, addressed to Ivan Abramovitch. This he placed aside.

‘May as well have his finger-prints,’ he said, and one of the officers present pressed Ivan’s hands on a piece of inky tin, and then on a piece of paper. The superintendent glanced casually at the impression.

‘All right,’ he said. ‘Take those handcuffs off. You may go, Mr Abramovitch.’

The Russian stood motionless, as though not understanding. Foyle wheeled about as though the whole matter had been dismissed from his mind, and caught Norman by the sleeve.

‘Drop everything,’ he said in a curt whisper. ‘Take a couple of men and don’t let that man out of your sight for an instant. I’ll have you relieved from the Yard in an hour’s time.’

‘Aren’t you going to charge him, sir?’ asked the other in astonishment.

‘Not likely,’ said Foyle, with a laugh.

CHAPTER XII

HELDON FOYLE walked thoughtfully back to Scotland Yard, satisfied that the shadowing of Ivan Abramovitch was in competent hands. With the strong man’s confidence in himself, he had no fears as to his decision to release the man. He was beginning to have a shadowy idea of the relation of pieces in his jig-saw puzzle. Ivan, he knew, ought to have been arrested if only for failing to give a satisfactory account of his possession of the pearl necklace. But the superintendent had, as he mentally phrased it, ‘tied a string to him,’ and it would not be his fault if nothing resulted.

It was well after midnight before he had finished his work at Scotland Yard. He had had a long interview with the Garden of Eden, in which promises were adroitly mingled with threats. In the result the ‘bunco-steerer’ had promised to keep his eyes and ears alert for news of anyone resembling Goldenburg. There was a string of other callers who had been discreetly sorted out by the superintendent’s diplomatic lieutenants. Finally, he pulled out the book which dealt with the case, and with the aid of a typist added several more chapters. With a sigh of relief, he at last sauntered out into the cool, fresh midnight air.

Nine o’clock next morning saw him again in his office. Sir Hilary Thornton was his first caller. Foyle put aside his reports at his chief’s opening question.

‘Yes, we’ve taken every human precaution to preserve secrecy,’ he replied. ‘Everyone who knows that it is not Grell’s body in the house has been pledged to hold his tongue. I have managed to get the inquest put back for three days, so that there will be no evidence of identification till then. That gives us a chance. And I’ve made out a confidential report to be sent to the Foreign Office, so that Grell’s Government shan’t get restive. Here are the latest reports, sir.’

The Assistant Commissioner bent over the sheaf of typewritten documents for a little in complete absorption. As he came to the last sheet he gave a start of surprise.

‘So you let this man Ivan go? Do you think that wise?’

‘I’m fishing,’ answered Foyle enigmatically. ‘I couldn’t have better bait than Ivan. There are three men sticking to him like limpets now, and a couple are keeping an eye on Sir Ralph Fairfield. I think that will be all right. Do you remember the Mighton Grange case? We knew there had been a murder, but couldn’t do anything till we found the body. Dutful, the murderer, would have slid off to some place where there’s no extradition, but for the fact that I had him arrested on a charge of being in the unlawful possession of a pickaxe handle. This affair is the converse of that. We can’t afford to have Ivan under lock and key.’

Sir Hilary Thornton bit his lip and looked steadfastly at the scarlet geranium on the window-sill, as though in search of enlightenment.

‘I believe I see,’ he exclaimed after a pause. ‘Ivan must have been something more than a valet. He’s a superior type of man, and the conclusion to be drawn if he knows that Grell is alive—’

‘Precisely,’ interrupted the superintendent.

‘Any result from the offer of a reward for Goldenburg?’

A flicker of amusement dwelt in Heldon Foyle’s blue eyes. ‘Yes. He has been seen by different people within an hour or two of each other in Glasgow, Southampton, Gloucester, Cherbourg, Plymouth, and Cardiff. Our information on that point is not precisely helpful. Of course, we’ve got the local police making inquiries in each case, but I don’t anticipate they will find out much. Still, it will keep ’em amused.’

The necessity of a conference broke up further conversation. Gathered in the building were some thirty or forty departmental chiefs of the C.I.D., the picked men of their profession. Most of them were divisional detective inspectors who were in charge of districts, and some few were men who had special duties. They were ranged about tables in a lofty room, its green distempered walls hung with stiff photographs of living and retired officials. Men of all types were there, from the spruce, smartly groomed detectives of the West End to the burly, ill-dressed detectives of the East. Between them they spoke every known language. Here was Penny, who had specialised in forgeries; Brown, who knew every trick of coiners; Malby, the terror of race-course sharps; Menzies, who had as keen a scent for the gambling hell as a hound for a fox; Poole, who was intimate with the ways of railway thieves and shoplifters. Not one but thoroughly understood his profession, and knew where to look for his information.