Полная версия

Barry Sheene 1950–2003: The Biography

Don Morley, a professional photographer and journalist since 1955 and one of the most respected photographers in the business, has a different take on Sheene’s aversion to the TT. Morley has probably taken more pictures of Sheene than anyone else and was always privy to the gossip and chatter in the paddocks of the racing world. ‘Barry made a bit of a name for himself slagging off the TT, but it was more to do with money than the dangers of the place,’ he said. ‘A normal Grand Prix lasted three days whereas the TT was a two-week event and it cost the riders an awful lot of money to compete there. There was very little prize money and it was awkward for the GP riders to get to the Isle of Man from the Continent. They had to drive to a port, get a ferry to England, drive again and then get another ferry to the Isle of Man which was a lot more difficult than just driving from the Spanish GP to the French GP, for example. Then they had to pay for a hotel for two weeks instead of just three days as well as all the other expenses. It was good for the organizers, but not the riders. This was in the days before lots of long-haul Grands Prix, and it just didn’t make financial sense.’

In 1972 Giacomo Agostini, who won 10 TTs and 15 World Championship titles, joined Barry’s protest after his close friend Gilberto Parlotti was killed on his TT debut. Ago said he would never race there again, and he kept his word. He was joined by Phil Read, though five years later he changed his mind and did race there again. The event was finally struck from the Grand Prix calendar after 1976, much to Sheene’s approval.

Sheene’s name was dragged up in the press for more than a decade whenever there were calls for the TT to be banned outright, and to this day there is still a lot of resentment among TT fans towards him. But it’s worth remembering that while Sheene hated riding at the TT (‘Why bother when it’s so much easier just to shoot yourself and get it all over with?’), it didn’t stop him racing on other pure road cricuits, most notably Oliver’s Mount in Scarborough, a treacherous, narrow and bumpy parkland circuit. And many Grand Prix circuits such as Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium and Imatra in Finland were armco-lined pure road circuits too.

Certainly Sheene’s criticism of the TT circuit ran somewhat in contradiction to his view on these other dangerous circuits, a fact he attempted to explain in Leader of the Pack. In justifying his decision to continue racing at the Oliver’s Mount track, he said, ‘As with any other circuit, if there are sections which you can’t tackle with confidence, it’s up to you to ride through those sections at the pace best suited to you. You can make up for lost time in other stretches, where there is less likelihood of hurting yourself.’ Surely that same theory could apply to the TT circuit as well as any other?

Mick Grant, himself a seven-times TT winner and a staunch supporter of the event, was one of Barry’s fiercest rivals in the seventies. He testified to Sheene’s abilities on road circuits despite his aversion to the TT. ‘Although Barry knocked the TT, we never actually spoke about it together. My regret with Barry was that he didn’t continue with the TT. Certainly the way he rode on pure road circuits like Scarborough and Imatra, there was no way that he couldn’t have done the TT. I mean, bloomin’ hell, Scarborough requires all the road racing skills you’d ever need, and he could do it. He certainly wasn’t slow round there.’

Still, from 1971 the Isle of Man was out of his hair for good and Barry was free to concentrate on the next round of the World Championship, to which he travelled in a bit more style – in his newly purchased caravan. To the modern GP follower this will sound more like a club racer’s accommodation, but in 1971 it was the last word in luxury. For some, this was the start of Sheene the poser. Upstart relative newcomers to the GP scene were expected to sleep on the floors of their oily vans rather than tow a caravan around like a wealthy American tourist, but to Sheene it just made practical sense. With a more comfortable bed and an area for cooking some decent food, he would be in better shape for the racing. And if it added to his glamour-boy image and helped to improve standards in the paddock, then so much the better. One thing Sheene certainly wasn’t slow to notice was that having a caravan greatly increased his pulling power with the ladies, and for Barry that fact alone was worth the extra expenditure.

Motorcycle racing on the Continent was huge in the seventies despite the utter dearth of professionalism involved in its organization and the lack of money available to its star performers. More than 150,000 people turned up to watch Sheene being narrowly beaten by Angel Nieto at the Dutch TT in Assen, one of the best-attended rounds on the GP calendar. The next meeting in Belgium got off to a bad start when Sheene was fined for spilling fuel on the track. He had been returning from a night out and was driving down the circuit to get to the paddock when his van ran out of diesel. He managed to bleed the fuel system and top the van back up, but not before sloshing some diesel onto the course. A vigilant Belgian policeman witnessed the incident and Barry was fined the now comedic-sounding sum of £6.60. He also incurred the wrath of his fellow riders who had to negotiate the slippery section of the track. But if the weekend got off to a bad start, it ended in the best possible way with Sheene taking his first-ever Grand Prix victory in the 125cc race. It was made a little hollow by the fact that Nieto had retired on the third lap, but Barry didn’t care; a first win is always a watershed, and he couldn’t have been more delighted. As he recalled, ‘Once I had crossed the finishing line, I could hardly contain myself. I wanted to get drunk, kiss as many girls as I could lay my hands on and just dance with joy. That was the proudest moment of my life up to then.’

A second in the 125 and a sixth place in the 250 race on his Yamaha in the East German Grand Prix were followed by a second GP win, this time in the 50cc class in Czechoslovakia. Kreidler had approached Sheene at the Belgian GP about riding one of their factory bikes to help out their full-time rider, Jan de Vries. For Sheene it was a chance to add to his start and prize money with minimum hassle as the factory team would take care of the bike. Race day didn’t start too well: Barry overslept and was ‘peacefully dreaming about two blondes’ when he was rudely awakened by members of the Kreidler team hammering on his caravan door. Pulling on his leathers and wandering bleary-eyed to the starting grid, Sheene was in no mood to go racing. He’d much rather have been left with his imaginary girlfriends. ‘When [I] set off,’ he recalled, ‘I think I gave a huge yawn; I was still half asleep. But I buzzed round as quick as I could in the wet with my head thumping and my teeth chattering with cold.’ In fact he buzzed round quickly enough to win the race from Nieto, who was by now firmly established as his arch rival no matter what class he seemed to race in.

He was certainly the man Sheene needed to beat in the 125cc class if he was to become the youngest ever Grand Prix world champion, and when Nieto’s bike expired during the Swedish round it began to look likely that Barry might just pull off a shock title win from the Spaniard. When Nieto also retired from the Finnish Grand Prix, Sheene held a 19-point lead with just two rounds to go and was being touted as the champion elect. Unfortunately for Sheene, a non-championship event in Hengello, Holland, then all but ruined his chances: he crashed, breaking his wrist and chipping an ankle. It was Barry’s first bad accident, the first time he had broken a bone while racing, and it’s easy to see now why top Grand Prix riders no longer take part in non-championship events, with the exception of the Suzuka 8-Hour race in Japan which remains massively important to the Japanese manufacturers who call all the shots.

Strapped up and in considerable discomfort, Sheene rode to a highly creditable third place in Italy behind Gilberto Parlotti and Angel Nieto and refused to blame his injuries for his failure to win, saying instead that his bike was simply not fast enough on the day. He remained in the hunt for the title, but it was to be yet another non-title event, the prestigious Mallory Park Race of the Year, that really did put an end to his hopes. It seems incredible that Sheene, having had a warning with his crash in Holland, would contest another race and risk further injury so near to the final round of the World Championship, but it was the norm for the time as well as being the only way riders could make enough money to survive a season. This time Sheene was thrown into a banking when his rear tyre lost traction. He was taken to Leicester Royal Infirmary for a check-up but, despite being in great pain, was discharged after being told he hadn’t broken anything. It was an extremely poor diagnosis: Sheene had in fact broken five ribs and suffered compression fractures to three vertebrae.

Oblivious to the fact, he travelled to Spain to take on Nieto for the final showdown in the world title chase. After again racing the 50cc Kreidler, which broke down on the last lap, Barry stooped over a fountain in the paddock to have a drink of water. That’s when he heard the disconcerting and agonizing ‘ping’ as one of his broken ribs popped out of place and threatened to burst through his skin. Never one to shirk from pain, Barry forced the rib back into place and taped up his torso to hold the offending bone in place long enough to last the race. Just making it to the Jarama start grid was the first of many superhuman efforts shown by Barry Sheene in his pursuit of racing glory. He and Nieto had a fantastic scrap all race long and were heading into the final stages when Barry hit some oil and slid off the Suzuki, his race and World Championship hopes over. After all his painful efforts, he had lost his grip on a title which had been so close because of a patch of oil that should have been cleaned up anyway. The only consolation for Sheene was that he didn’t further aggravate his injuries in the crash.

It might have been a disappointing way to end what had been a great year, one that had delivered 38 race wins, but Sheene didn’t dwell on it for long. Having so nearly taken a world crown at his first attempt, he was confident he could definitely lift one the following year. For the 1972 season, he signed for Yamaha to ride its 250cc and 350cc machines in what was his first season with a factory team. At last he was being paid to go racing. The year started off well, and Sheene picked up his first-ever 500cc class win at the King of Brands meeting over Easter. But that only fuelled his confidence and added to the complacency with which he faced the Grands Prix. Things went wrong from the very first round when both Yamahas suffered mechanical breakdowns. The bikes were both slow and unreliable, and Barry didn’t help matters when he badly broke a collarbone during the Italian Grand Prix. The only highlights of the GP season were a third place in Spain and a fourth place in Austria, both in the 250cc class, and that was hardly a step up from the year before when he’d won four Grand Prix races. Sheene was acutely aware of the fact, too.

Such a disastrous season led to bad feelings between Sheene and his Yamaha team and he was desperate to leave by the end of the year to prove that it had been the bikes and not his riding at fault. These bad feelings would come back to haunt Barry years later when he once again rode a Yamaha. Those same lowly mechanics from the 1972 season had risen up the ranks to become senior personnel by 1980, and whenever he asked for a favour Sheene discovered that they had long memories. Had he kept his views on the 250 Yamaha to himself, or at least confined his criticism of the bike to behind closed doors, there would have been no problem. As it was, he made no secret of what he thought of the bike, and there is no surer way to offend the Japanese corporate psyche. Still, Sheene was prepared to shoulder some of the blame for his worst year to date: ‘That poor year in 1972 taught me a salutary lesson about the dangers of becoming big-headed. Over-confidence was the root of my problems.’

With Sheene’s reputation having taken a bit of a battering, he was really out to prove himself in 1973. He had a new contract with Suzuki and a new championship challenge beckoned: the FIM Formula 750 European Championship, in many ways the predecessor of the current World Superbike Championship. The Formula 750 Championship was, to all intents and purposes, a world championship even though it didn’t enjoy the prestige of being conferred with official world-class status. The calendar of dates was just as gruelling as the Grands Prix, and the calibre of riders almost as impressive.

The new breed of 750cc superbike racing had taken off in America in the early seventies and reports had reached Sheene that Suzuki’s new three-cylinder 750 had been clocked at 183mph in testing – allegedly the fastest speed ever attained by a race bike at that time. Sheene couldn’t wait to get his hands on one. Despite the fact that he had cut his teeth in 125 and 50cc racing, he now referred to the smaller-capacity bikes as being very ‘Mickey Mouse’ and was determined to prove he could win in the world’s largest-capacity racing class on what he considered ‘real men’s bikes’. Sheene duly got a Suzuki triple from the US where his brother-in-law, Paul Smart, would be racing one. Smart had been an arch rival of Sheene’s over the past few years but the pair had continued to have a friendly relationship. Barry had been as pleased as anyone when Paul tied the knot with his sister Maggie at the end of 1971, a marriage that still stands today and which produced current racer Scott Smart, Sheene’s nephew.

When Barry eventually took delivery of his new Suzuki it was immediately apparent to him that it was not the exotic piece of machinery he had been expecting. Much midnight oil was burned as he slotted the engine into a Seeley chassis and rebuilt the bike to a more competitive spec. In the end, his hard work paid off. Despite winning only one round of the eight-round championship, Sheene’s two second places, a third and a fourth meant he accumulated enough points to win the title ahead of Australian Jack Findlay, John Dodds and his own team-mate Stan Woods. Of the remaining rounds, he had two non-finishes and was disqualified from the British round at Silverstone for switching bikes between the two race legs. It was Sheene’s most prestigious championship win to date, and he proved that he really had mastered larger-capacity machines by adding the Motor Cycle News Superbike title, Shellsport 500 title and King of Brands crown to his collection.

Sheene was now really starting to make a name for himself, not only as a racer but as a great PR man and a bit of a grafter, as John Cooper explained: ‘Barry was always a very determined chap. He worked on his bikes a lot and they were always nicely prepared and presented. He used to try hard and he was very professional. Preparation is the thing with bikes, and he was always keen, fiddling about, changing the sprockets, altering the forks and the springs – not like today when riders just come in the paddock and dump their bikes on their mechanics. He wasn’t shy of grafting. Years later I used to go down to his house when he lived at Charlwood and all his spanners were laid out neatly in his workshop and his helicopter sat there all nice and clean. He was very organized.’ Cooper, like Chas Mortimer, had known Sheene long before he started racing and was happy to help Frank’s boy in any way he could. ‘We used to help each other out, lending each other bikes and stuff; you know, we were just friends really. But he didn’t need much steering because he always had the makings of being the right man for the job, and that was apparent even in the early days.’

After such a disappointing year in 1972, Sheene was most definitely back. Readers of MCN recognized his achievements by voting him their Man of the Year for the first of five times in his career – a record that stood for almost two decades until Carl Fogarty accepted the award for a sixth time in 1999. Moreover, Sheene’s F750 victory was enough to convince Suzuki that he deserved a ride on their all-new RG500. The four-cylinder, 500cc Grand Prix weapon was to become a racing legend in its own right, winning four world titles between 1976 and 1982, but in those early days it was an absolute beast to ride, all power and no handling. When Sheene first tested the bike in Japan at the end of 1973, he found, like everyone else who had ridden it, that the bike had a nasty habit of weaving viciously at speed and pulling wheelies under power, but it was still the fastest bike he’d ever ridden and he proved it by knocking one and a half seconds off the Ryuyo track record in tests.

The plan for 1974 was not only to defend his Formula 750 title but, more importantly, to contest every round of the ultimate motorcycle series – the 500cc Grand Prix World Championship. It would be Sheene’s first ever year in the premier class and he knew the RG500 was up to winning races once the handling was sorted out. But that was easier said than done, and 1974 was to prove a tough baptism for Sheene. The gremlins in the RG’s handling were never truly rooted out that season, and the bike was further plagued by mechanical faults, as most new machines are. Gearboxes and drive shafts were particularly prone to breaking, and Barry had his fair share of crashes, which only added to his problems.

The first outing for the bike was in March at the Daytona 200 race in Florida. It was Barry’s first time there as well as the Suzuki’s, and that meeting inadvertently led to Sheene adopting the now famous number seven. As he told me during an interview for Two Wheels Only magazine, ‘Seven was always my favourite number even as a kid. I’d want seven this or seven that. Then, when I went to Daytona in 1974, I asked what numbers were available. The Americans usually give new riders really high numbers, but Mert Lawill had retired so seven was available. I was well chuffed.’ The lucky number seven wasn’t the only thing Sheene took away from the States. He also latched on to the American habit of displaying the number for all to see while brightening up his racing attire, too. ‘The Americans made you wear your number on your helmet and leathers too, which was even better, and I kept the look when I got back to Europe afterwards.’

It was just as well that Barry brought something away from Daytona because ignition trouble ruined his chances of getting a result in the race. After that, a fine second place in the first Grand Prix of the year proved to be a false indicator of what to expect. Along with most of the other riders, Sheene sat out the German race in protest at the lack of straw bales surrounding the course, then finished third in Austria after suffering the humiliation of being lapped by Giacomo Agostini and Gianfranco Bonera. Four consecutive non-finishes followed for the fast but fickle Suzuki, and a fourth place in the final Czech round was little consolation for a bitterly disappointing 500cc GP debut season in which Sheene had managed to finish only sixth overall. The defence of his Formula 750 title had been a bit of a wash-out too; Barry hadn’t really had time to concentrate on that series as well as the Grands Prix and had had to give second best to the new, super-fast Yamahas. There were brighter moments, though, like scoring the RG500’s debut win at the British Grand Prix, even though it was a non-championship event and as such shouldn’t really have been called a Grand Prix at all. Barry also won the Mallory Park Race of the Year as well as the Motor Cycle News Superbike Championship and the Shell Oils 500 title, salvaging some home pride after a difficult year.

Suzuki were extremely disheartened, though, and ready to throw in the towel with the RG500 project until Sheene insisted on spending five gruelling weeks in Japan working on the bike to turn it into a winner. By the time he was through, Sheene was convinced he could challenge for the 1975 World Championship. But first there was the Daytona 200 to think about, and this time it would make him an international superstar – for all the wrong reasons.

CHAPTER 3 PLAYBOY

‘Two women sharing my bed was old hat as far as I was concerned.’

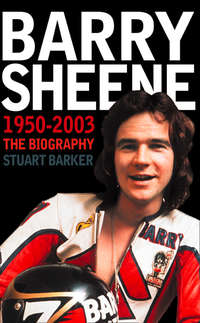

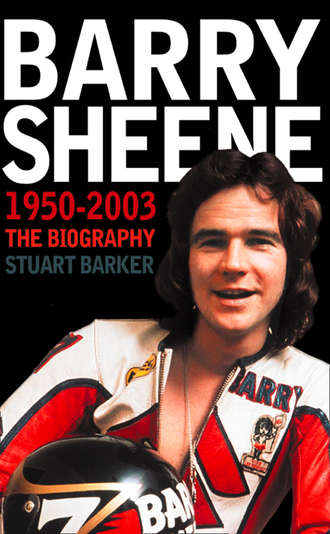

It’s fair to say that there is no long-standing tradition of motorcycle racers being pin-ups, heart-throbs, playboys or style gurus, but Barry Sheene was all of these things and a whole lot more, besides being a phenomenally successful racer. Ever since his first sexual dalliance over a pool table in the crypt of a London church, Barry never left anyone in any doubt about his sexual orientations. Certainly wealth, fame and the perceived glamour of his chosen profession helped considerably in his conquests of the opposite sex, but his boyish good looks and easy charm were already in place long before any material success.

Sheene was born with a natural blond streak in his otherwise brown hair which, he claimed, was a result of his mother having received a nasty shock during pregnancy when a child walked out in front of her car. According to Sheene, who presumably got the story from his mother, the incident was enough to leave a birthmark on his head which in turn caused the blond streak to grow from it; he related this story many times to prove he was not dyeing it and hence ‘not turning into a pouffo’. It seems Sheene was destined to stand out from the crowd even before he was born. Blond streak aside, the long, flowing locks were all his own doing, together with overgrown sideburns a fashion ‘must’ in the seventies. ‘Having your hair cut in the seventies,’ he observed, ‘was like having your legs amputated. It just wasn’t on.’

Sheene was not built like an athlete, but his frame seemed to serve him well enough when it came to the fairer sex, and what he lacked in the Adonis physique stakes he more than made up for with his ready wit and devil-may-care attitude. In 1973, his looks were deemed worthy of an appearance in Vogue magazine, an accolade of which no bike racer before or since can boast. The man behind the lens was none other than David Bailey, one of England’s most celebrated photographers, more used to working with Mick Jagger, the Beatles, Salvador Dali and Jack Nicholson than with motorcycle racers. The Vogue job wasn’t Sheene’s only modelling stint, either; his other assignments included posing in a pair of underpants alongside a semi-naked woman in the Sun – again, not the most traditional extra-curricular activity for a bike racer, a point that was not lost on Sheene. ‘I reckon I finally destroyed the popular concept of a biker when I was pictured in the Sun. This wasn’t quite what traditional bike enthusiasts had come to expect, but I’m sure it helped to undermine the myth that all those who rode motorcycles are dumb, dirty and definitely undesirable.’ Sheene even went on to have his own weekly column in the Sun in the seventies, which gave him a much coveted mouthpiece in the country’s biggest-selling newspaper.

Image was always important for Sheene, and his greatest role model was Bill Ivy, whom he had known and admired since childhood, as he admitted in an interview for Duke Video in 1993. ‘I suppose one of the biggest influences when I’d just started racing was Bill Ivy because [he] used to race for my dad and was a good mate of mine and I loved his lifestyle. I mean, he was always surrounded by crumpet, all young ladies. I suppose I sort of modelled myself on Bill in that he always used to dress the way he pleased and his lifestyle was a lot of fun, and the woman side of it was the bit I envied the most.’ Sheene’s former rival Mick Grant witnessed Barry’s dealings with the media first-hand and reckoned he played up this playboy image. ‘He was just very good with the media. He was probably better with the media than he was at riding, and he was okay at riding.’

Anything Barry did to improve his own personal standing and image usually seemed to have a positive effect on motorcycle racing in general. He might have had to get rid of the saucy patches he wore on his leathers (‘Happiness is a tight pussy’; ‘I’ll make you an offer you can’t refuse’) once he became famous, but he was still capable of attracting attention to himself as a rider. White leathers when most others wore black, the colourful Donald Duck motif on the helmet, the gimmick of making a victory V sign whenever he won a race (which signified victory to the spectators while appearing as something very different to the riders behind him), a caravan to take girls back to rather than an oil-stained van – all these things helped Barry’s personal pulling power as well as the overall image of the sport.