Полная версия

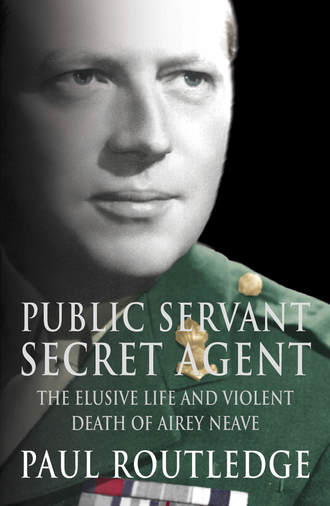

Public Servant, Secret Agent: The elusive life and violent death of Airey Neave

When the war rudely interrupted this agreeable scene, Neave was among the first to volunteer for active service. His experiences at Calais in 1940, his subsequent capture and imprisonment by the Germans, followed by escape from Colditz in 1942, brought him to the attention of British military intelligence on his arrival in neutral Switzerland, whence he was fast-tracked back to Britain and immediately recruited to MI9, the escape and evasion organisation for Allied servicemen. Nominally an independent section of the war effort, MI9 was in fact – and much to Neave’s delight – a wholly-owned subsidiary of MI6, the Secret Intelligence Service.

Neave worked in this clandestine operation for three years, training agents to be sent into the escape ‘ratlines’ of Occupied Europe and debriefing escapers before following hard on the heels of the invading Allies in July 1944. His service also took him to forward engagement areas in France, Belgium and Holland, where he successfully spirited out remnants of Operation Market Garden, the abortive Arnhem raid. He ended the war a DSO and an MC. The closing stages of the war found Neave in Paris and Brussels in 1944 running British operations to grant awards and medals to MI9 agents who had helped Allied servicemen to escape or evade the enemy. Such operations had a further, undisclosed objective: that of identifying agents who would continue to be valuable after the war in the context of a Cold War (or worse) between Western nations and the Soviet Union. The bureaux drew up lists of ‘reliable’ contacts who would be useful in the event of a Soviet invasion of Western Europe. It was sensitive work, not least because so many of the Resistance were Communists and at this stage still sympathetic to the Soviet Union.

This covert enterprise, known as Operation Gladio, brought together a wide range of skills, from those involving psychological warfare and sabotage to escape and evasion. Gladio’s purpose was to set up ‘stay-behind’ units that would be active in a Europe threatened or even occupied by the USSR. Their existence has never been officially recognised, nor disclosed. Stephen Dorril argues: ‘It appears that sections of MI6 were already thinking in terms of the next war, and part of that was a fear that the Red Army would continue from Berlin and go straight to the Channel coast. They wanted stay-behind units against the Red Army in the same way that they wanted them against the Germans. Some of these units put in place in 1944 were almost immediately being resurrected as anti-Communist units – ratlines for escape and evasion.’7 SOE would take on the sabotage role, while Neave’s old firm would carry on as before.

But in post-war austere Britain the climate was against such initiatives: money for secret operations was getting tight and it was difficult to sustain a continuity between wartime and post-war groups. The Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee disapproved of such activities and the emphasis shifted from formal policy to the unofficial but well-connected world of former intelligence operatives. The thread continued in dining clubs, the Special Services Club and in the part-time Territorial Army. MI9 was reborn as Intelligence School 9 (TA) and Neave was commanding officer from 1949 to 1951, at a time when he was seeking to enter public life as a Conservative MP. IS9 later became 23 SAS Regiment, based in the Midlands, with a role to counter domestic subversion.

While his political career blossomed in the late 1950s, Neave’s links with the secret state necessarily became more obscure. It is known that sometime in 1955, he approved the appointment of British spy Greville Wynne as the representative in Eastern Europe of the pressure-vessel manufacturers John Thompson, of which Neave was a director. Like Neave, Wynne had worked for MI6 during the war. He returned to spying in the mid fifties and used his business trips behind the Iron Curtain to recruit the Soviet spymaster Oleg Penkovsky, before being unmasked and jailed. He was freed in exchange for Russian agent Gordon Lonsdale. Wynne confessed that ‘after a time, espionage is like a drug, you become to a greater or lesser extent addicted.’ It is inconceivable that Neave was unaware of Wynne’s MI6 role. Neave continued to meet with his old comrades, and to harbour fears of Communist subversion, but to the world at large he was a quiet, thoughtful man, assumed by commentators to be on the centre-left of his party. After his relatively brief, and not very glorious, ministerial career at the Transport and Air departments, he returned to the back benches in 1959. From there he campaigned successfully for compensation for British survivors of Sachsenhausen concentration camp, but unsuccessfully for the release from Spandau prison of Nazi war criminal Rudolf Hess, whose flight to Scotland in May 1941 had delivered him into British hands. He sought to assuage the suffering of refugees through his voluntary work for the UN High Commission for Refugees. In addition, he became a governor of Imperial College, London, and chairman of the Commons Select Committee on Science and Technology.

But behind the façade there still burned a sense of mission. He watched with apprehension the collectivist drift of Britain and the growing power of the trade unions. He believed the danger of expansionist Communism was both real and present and he believed fiercely in freedom. In the record of his wartime exploits, They Have Their Exits, he laid down his credo, ‘No one who has not known the pain of imprisonment understands the meaning of liberty’, a line that is engraved on the walls of the museum in Colditz castle as a testament to his dedication. The title of Neave’s book was taken from As You Like It: ‘All the world’s a stage/And all the men and women merely players; / They have their exits and their entrances; / And one man in his time plays many parts.’ No quotation more satisfyingly expresses the different sides of Airey Neave. He was a man who played many parts but the drama was discreet and informal. He played many roles behind the scene. Given the nature and scale of his involvement with the security services, it may also be argued that Neave valued his own freedom and that of those around him so much that he was prepared to countenance extreme measures to safeguard his concept of liberty. Roger Bolton, a television producer who knew him and put together a documentary on his assassination, argues the paradox that Neave was a moral man willing to do things that immoral people were not: ‘If necessary, he took the gun out and there were difficult things to be done but for the most honourable of reasons.’8

Why did he imagine that he knew better than the rest? Neave was not a particularly gifted politician, and it seems unlikely that he would have risen to the ranks of a Conservative Cabinet in the ordinary way. And yet, of the Tory MPs of his generation, Neave left the most indelible mark on political history by riding an inner conviction that his grasp was somehow superior. He felt he should turn that comprehension to common advantage; he was a spook who believed he knew, and who acted on his beliefs and loyalties. He was not alone in such self-assurance, which is the stock in trade of the spy. Although he was not an orthodox MI6 officer, Neave shared the outlook of the security services and remained close to them. He may have been an elected politician in a democracy, but he shared the misgivings about the world around him expressed most cogently by George Kennedy Young, with whom Neave was actively acquainted.

While still deputy director of MI6, some time in the late 1950s, Young issued a circular to his staff on the role of the spy in the modern world. He noted scathingly the ‘ceaseless talk’ about the rule of law, civilised relations between nations, the spread of the democratic process, self-determination and national sovereignty, respect for the rights of man and human dignity to be found in the press, in Parliament, the United Nations and from the pulpit: ‘The reality, we all know perfectly well, is quite the opposite, and consists of an ever-increasing spread of lawlessness, disregard of international contract, cruelty and corruption. The nuclear stalemate is matched by a moral stalemate.’ Young further stated that ultimately it was the spy who was called upon to remedy situations created by the deficiencies of ministers, diplomats, generals and priests, and that the spy found himself ‘the main guardian of intellectual integrity.’9 Neave’s nature is readily discernible here: the man who keeps himself to himself, but knows. The man who hates ostentation but goes about his dedicated business with a discreet energy, working for his Queen, country and traditions.

The Britain of the early 1970s, with its crippling strikes, inflation and civil war in all but name in Ulster, called forth men like him on a mission to save the country they loved. At least, that was the way they saw it. From the recesses of the security services, from the upper reaches of the City, from London’s clubland, and from the right of the Conservative Party, came volunteers eager to fight the good fight, Neave among them. But if his greatest contribution to politics was to mastermind the coup that dethroned Edward Heath (employing the ‘psy-ops’ skills he had acquired in his intelligence years) and brought the leadership of the Tory Party to Margaret Thatcher, it did not rob him of a taste for the covert. Soon after Thatcher took over, amid nervousness in the City as inflation soared to 25 per cent and with the pound at little more than 70 per cent of its 1971 value, Neave attended a reception of Tory MPs given by George Kennedy Young, by now the ex-deputy director of MI6. General Walter Walker, former Commander-in-Chief of NATO’s Northern Command, was also there. In 1973, at the height of industrial unrest, he had set up Civil Assistance, a quasi-private army of ‘apprehensive patriots’ to give aid to the authorities.

It was never called upon to carry out this function but the theme did not lose its attractions. Neave became involved in Tory Action, a right-wing pressure group within the party, and the National Association for Freedom (NAFF), set up in late 1975 to counter ‘Marxist subversion’. This organisation had more success than Civil Assistance, notably in the legal harrying of strikers. However, the most intriguing – and sinister – of Neave’s operations came in 1976 when he became involved with Colin Wallace, an army intelligence officer working for Army Information Policy in Northern Ireland. Operation Clockwork Orange, initially created to undermine republican terrorists through a disinformation machine to the media, would spread its tentacles into the higher echelons of British politics to probe and exploit the weaknesses of key figures. Aware of Wallace’s MI5 background and his disinformation programme, Neave would maintain his contacts with him when he was appointed Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary.

Neave’s connections with the secret state, past and present, gave rise to speculation that he could also be given the task of liaising between the government and the intelligence services – a job similar to that undertaken by Colonel George Wigg, Paymaster-General in Harold Wilson’s government.10 Wigg, known in Parliament as ‘the Bloodhound’, certainly admired Neave, describing him as ‘a smart operator who learned from me’. Plainly, the spooks’ mutual admiration society crossed boundaries. It also influenced intelligence policy. Neave’s high opinion of Maurice Oldfield was almost certainly instrumental in Thatcher’s decision to appoint the former head of MI6 as Coordinator of Security and Intelligence in Northern Ireland in October 1979. Oldfield, in charge of MI6 from 1965 to 1977, had survived a bomb attack on his London flat in 1975.

In parliament, Neave gave full support to Roy Mason, the hard-line Labour Ulster Secretary, urging him to go further and ‘pick off the gangsters’ of the IRA. Neave’s policy for Ireland, insofar as it was understood in London and Dublin, was a twin-track strategy of devolving some powers to local councils in Ulster, coupled with the toughest possible military crackdown on republican terrorism. He had no time for power-sharing between nationalists and Unionists, arguing that it had failed and should not be tried again. It was the agenda of a soldier rather than a politician who understood Ireland and the Irish. Nonetheless, his blood-curdling warnings of the wrath that was to come when the Conservatives took office made republicans sit up and take notice of him. They feared him. He believed he had a special insight into the guerrilla mind. ‘I know how the IRA should be dealt with because I was a terrorist myself once,’ he told an Irish journalist.11

Neave would have had the British army at his disposal. Indeed, he still thought of himself as ‘one of them’. He believed that specially trained soldiers should be used to ‘get the godfathers of the IRA’ and rejected any suggestion of amnesty for convicted terrorists as part of a peace deal. It was quite clear that the price of liberty in Ulster could involve the annihilation of those engaged in violence for political ends. This Cromwellian solution was what Neave meant by liberty. The policy was to bring about his own death before it could be implemented.

Yet, for all the convulsions created by Neave’s death, the secret state has left his assassination in a limbo of oblivion. Apart from an (officially) abortive police enquiry, which also involved the security services, there has been no attempt to investigate Neave’s life and death. Sources as diverse as Enoch Powell and ex-collaborators with Neave believe that the authorities themselves may have had a hand in the bloody affair. Even his own daughter Marigold believes the facts have been suppressed. ‘I think there was a cover-up,’ she said across her kitchen table in deepest Worcestershire one cold January morning. ‘They only say “he died a soldier’s death”.’ 12

2 Origins

Airey Neave was born at 24 De Vere Gardens, Knightsbridge, a stone’s throw from Kensington Palace and just down the road from the Royal Albert Hall, on 23 January 1916. His father, Sheffield Airey Neave, continued an eccentric family tradition and burdened his son with family surnames, adding to his own that of his wife Dorothy Middleton. Thus, Neave was christened Airey Middleton Sheffield. As he grew up, Airey began to hate his whimsical collection of names, so much so that he rechristened himself Anthony during the war years and only reverted to Airey when he entered public life.

Airey must have quickly appreciated that his family was steeped in history. Of Flemish – Norman origin, the Neaves came to England in the wake of William the Conqueror and settled in Norfolk about 200 years before the earliest recorded member of the family, Robert le Neve, who lived in Tivetshall, Norfolk, in 1399. His forebears lived in villages around Norwich where they became landowners and sheep farmers. As they prospered in the wool trade, some le Neves struck out further afield, to Kent and Scotland, but they stayed chiefly in East Anglia, gaining social distinction. Sir William le Neve, a native of Norfolk, was Clarenceux King-of-Arms at the College of Heralds in London in 1660.

The failure of the wool trade in the mid-seventeenth century drove some enterprising members of the family to seek their fortunes in London, with mixed results. One generation was wiped out by the Black Death in the 1660s (the victims are reputedly buried under a church in Threadneedle Street) but Richard Neave, who lived from 1666 to 1741, fared better, establishing a prosperous business in London, with offices in the Minories. He made most of his wealth from the manufacture of soap, a new and very fashionable product for the period. He bought land east of London outside the city limits, where his sons began to establish what would become London docks. His business also expanded overseas, with estates in the West Indies, and he put his accumulated resources into his own bank in the City.

The business further prospered through judicious marriages and Richard’s grandson, bearing the same name, bought the Dagnam estate in Essex, so beginning the family’s long connection with the county which remains to this day. His grandson became Governor of the Bank of England in 1780 and a baronet in 1795. The family crest, a French fleur-de-lis, with a single lily growing out of a crown, long predates the adoption of the Neave motto, Sola Proba Quae Honesta, which translates literally as ‘Right Things Only Are Honourable’. Speculation about possible royal connections linked to the appearance of a crown on the crest, admits Airey’s cousin Julius Neave, has given rise to ‘some fanciful but quite unsubstantiated theories’ as to the family’s origins.

However, the family’s upward mobility was undeniable. Sheffield Neave, another Governor of the Bank of England (1857–9), gave his Christian name to succeeding generations (some noted for their longevity), one of whom was Airey’s grandfather, Sheffield Henry Morier Neave (1853–1936), well-known in Essex for his eccentricity. He inherited a fortune while still at Eton, and went up to Balliol College, Oxford, where he acquired a degree but showed no inclination to pursue a profession thereafter. With plenty of money and no need to work, he indulged his passion for big game hunting, spending long periods in Africa, where he became convinced that control of the malarial tsetse fly was the only bar to great agricultural prosperity in sub-Saharan Africa. He returned to England and studied to become a doctor in middle age, eventually rising to become Physician of The Queen’s Hospital.

At the age of twenty-five, Sheffield Neave married Gertrude Charlotte, daughter of Julius Talbot Airey. They lived at Mill Green Park, Ingatestone, which was to become the family seat, and it was to Mill Green that Neave would return after his incarceration in Colditz. He dreamed vividly of the house during his captivity, and lyrically described its chestnut trees, its May blossom and the white entrance gates in his first book, They Have Their Exits.

Sheffield Neave had his own Essex stag hounds and was a legend in the field. Ever the eccentric, the stags he hunted were not wild but carted to the meet in the same vehicle as the hounds: ‘There was never any question of the hounds killing the stag, who was much too valuable to be lost in this way,’ Julius Neave has explained.1 ‘They all came home to Mill Green at the end of the day and were stabled together.’ Sheffield gave up stag-hunting at the turn of the nineteenth century, complaining that ‘Essex is getting too built over’, but he rode to hounds until nearly eighty, when he took up golf instead. Long after his death a particularly vicious jump over a ditch and stream was still known as ‘Neave’s leap’.

Gertrude Neave, the epitome of a Victorian lady, was an accomplished pianist and also composed music. She came from a distinguished family, one of her relations being General Lord Airey, chief of staff to Lord Raglan, Commander-in-Chief of the British army in the Crimean War. He was, reputedly, the ‘someone who blundered’ over confused orders which led to the Charge of the Light Brigade. Gertrude and Sheffield had two sons and two daughters. The elder son, Sheffield Airey, born in 1879, was Airey Neave’s father; the younger, Richard, became a professional soldier and saw service in the Boer War, India and in Gallipoli in 1916. He also served in Ireland during the Troubles of 1920–22, and Airey may well have heard stories of ‘the Fenians’ from his uncle.

Airey’s father went to prep school in Churchstoke, in the Welsh Marches, and then (as befits the grandson of a Governor of the Bank of England) on to Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford, to read natural sciences. He inherited his father’s fascination with Africa and the diseases spread by insects. In the years before the Great War, he travelled in 1904–5 on the Naturalist Geodetic Survey of Northern Rhodesia, and to Katanga as entomologist to the Sleeping Sickness Commission of 1906–8. On his return from Africa, he served in a similar capacity on the Entomological Research Committee for four years before being appointed Assistant Director of the Imperial Institute of Entomology at the age of only thirty-four. He was to hold the post for thirty-three more years and then took over as director in 1942, the year Airey escaped from Colditz, before retiring in 1946.

A big, dominant man with a moustache, Sheffield Neave was a distant figure, immersed in his scientific work and given to a Victorian aloofness from his children. After Airey’s birth, the family moved to a house in High Street, Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, where four more children were born: Averil, Rosamund and Viola, and then a second son, Digby. Dorothy Neave, descended from an Anglo-Irish family, played a traditional role in the family: she ran a comfortable if unostentatious household. There were servants and appearances to keep up but Dorothy was often unwell and died of cancer in 1943 when Airey was working for MI9. Airey’s daughter Marigold says that he did not have a good relationship with his father. ‘He was very much a scientist. Perhaps that is what made him not very easy to get on with. He was very remote, a very Victorian figure.’2 If not physically robust, Airey’s mother possessed a mental determination unusual in her position. ‘Grandmother was quite forward-looking, quite progressive for those days. She was a liberal with a small “l”,’ recorded Marigold. ‘His childhood was not very easy. His mother was very often ill. Officially, he looks very much like her, but he never talked about her. He talked about his father, but not in very glowing terms. He was a very strict character, powerful and good-looking: a strong face, very dark eyes. And physically he was very tough. It was a clash of personalities.’ Group Captain Leonard Cheshire, the Dam Busters war hero, friend and contemporary at Merton, would come to a similar conclusion. Neave, he wrote, was highly independent and always ready to follow his inner convictions. ‘No matter what the opposition, he would often do things that were a little wild, though always in rather a nice way and never unkindly.’ This trait endeared him to school and university friends, ‘but possibly had a different effect upon his father who one has the impression did not always give him the encouragement which inwardly he needed. Thus, at a very early age he learned to conceal his inner disappointments.’3

Airey Neave attended the Montessori School in Beaconsfield, a progressive school where his individuality was respected. In 1925, at the age of nine, he was sent to St Ronan’s Preparatory School in Worthing, Sussex. The headmaster, Stanley Harris, was a remarkable man who had played football for England, and captained the Corinthians, the famous amateur team. The essence of his educational philosophy was captured in the school prayer, known as Harry’s Prayer, which ran:

If perchance this school may be A happier place because of me Stronger for the strength I bring Brighter for the songs I sing Purer for the path I tread Wiser for the light I shed Then I can leave without a sigh For in any event have I been I.

Set in several acres on the outskirts of Worthing, St Ronan’s placed great emphasis on academic excellence, sport and self-development. In many ways an archetypal English prep school – numbering future air vice-marshals and an Asquith among its pupils – it was built in red brick and sat against the backdrop of the South Downs. Despite the usual rigours of such places, the school had a patriotic rather than militaristic air about it. There was no cadet corps but boys were taught shooting, and from time to time a former army sergeant – so old that he had been with Kitchener at Khartoum – came to the school to teach gymnastics and boxing. With their days filled, in the evenings boys were allowed to pursue their own interests. In Neave’s time, some of them built a primitive radio – a crystal set with ‘cat’s whiskers’ tuning. Others drew maps of imaginary countries, bestowing such nations with complex railway timetables. Essentially, they had to learn to make their own amusement, and learn to fend for themselves, all of which helped develop a form of independence.

In 1926 Stanley Harris died of cancer and his place was taken by his brother, Walter Bruce (Dick) Harris, then a housemaster at nearby Lancing College. If Airey was a better than average pupil he was not spectacularly so, and seems to have been suited to his first form which was ‘composed mostly of boys with plenty of ability, one or two of whom however have no great idea of work’. In 1925, he won a combined subjects prize, but in class 1A in 1927 he was fourteenth. By the following year he had crept up to eleventh, then ninth and finally sixth, with 1, 205 points. That autumn, he also won the Latin prize. The highest placing he received was third, but mostly he fluctuated around the lower end of the top ten. The boys were expected to take a full part in the life of the school. Airey played a waiter in the school play in 1928, and the St Ronan’s magazine observed: ‘A word must be given to Neave who by progressive stages became the perfect waiter.’ Praise indeed.