Полная версия

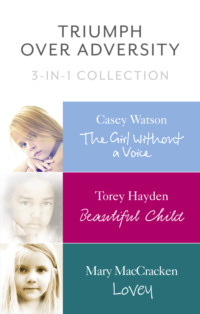

The Girl Without a Voice: The true story of a terrified child whose silence spoke volumes

I knew I was last-chance saloon where Henry was concerned. If he didn’t change his fighting ways, he’d be permanently excluded, and I felt sorry for him. I had a bit of a soft spot for him too.

I looked at him now. ‘Henry,’ I chided, ‘I know you didn’t beat those boys up, just like I know that, being the oldest here, you’re going to step up to the plate. You’re going to help me, aren’t you? Help make sure that Imogen doesn’t get a hard time? Point out to the younger ones that she’s just a little different – can you do that? I can count on you to do that for me, can’t I?’

I watched Henry digest this and break into a grin. ‘I can be like your terminator, Miss, can’t I? If the others pick on her I can zap them with my bionic arm, can’t I? They’d soon stop saying stuff then, wouldn’t they?’

I laughed. ‘Er, I don’t think I want you to be doing any zapping. But it would be a great help if you could just watch over her for a few days – you know, when I’ve got my back turned and stuff.’

This seemed to make him happy, because as he walked back to the group, his shoulders high, he announced that, as the oldest, he was officially looking out for the new girl. ‘So no funny business,’ he said, before turning back to me. Upon which he winked. I had to stop myself from laughing out loud.

Gavin’s take on the apparent oddity was more practical. After a barrage of questions – Why couldn’t she talk? Had she got ADHD? Was she ‘on meds’? – he had the solution. ‘You should give her some Ritalin,’ he observed. ‘That’ll sort her out.’

One of my rules, given that I tended to spend my days with challenging children, was that easier-said-than-done-thing at the end of the working day of making a determined effort to take off my ‘miss’ hat and put on my ‘mum’ one.

I always smiled to myself at school when the kids themselves found it difficult; when – at least at the beginning of the day, anyway – they would accidentally call me Mum instead of Miss. They’d always blush then, often furiously, but I took it as a compliment. I’d never wanted to be the sort of teacher who kept such a distance from their charges that it was a mistake that no child would ever make. Quite the contrary – I took these slips as evidence I was working in the right job; that I was someone they felt comfortable around. That was important – if they were comfortable enough to forget themselves around me then I would be in so much better a position to support them. Which could make the difference, in some cases, between returning to mainstream classes, back among peers, learning, and travelling even further down the road to isolation.

And I also knew that my drive to help them was partly as a consequence of seeing first hand how much that mattered, through helping Kieron with the many challenges of growing up with Asperger’s.

Which he was still doing, as I observed when, letting myself into the house and slipping off my coat and shoes, it was to find him slumped on the sofa in front of the telly, as was currently his habit.

He was waiting, I knew. Waiting for me to come in and give him his tea, before Mike and Riley both got home from work. I went into the kitchen and pulled out a plate and some cutlery.

‘Honestly,’ I called to him as I dished out some casserole from the slow cooker, ‘why you can’t wait till the others get home is beyond me, Kieron. And if you can’t wait, you could at least get off the sofa and help yourself to something.’

He looked across and gave me one of his pained looks as he turned down the TV volume. ‘Oh, Mum,’ he moaned. ‘Don’t get on at me. I’m stressed out enough as it is!’

‘And what exactly have you got to be stressed about?’ I asked him as I took the bowl of steaming casserole through to the dining-room table. I had strict rules about the eating of meals and where it was allowed to happen, even if I was generally a little on the soft side when it came to my son. ‘Come on,’ I said. ‘Come through here and eat this before it gets cold. So, tell me,’ I added as I set it down, and glancing at the evidence of a day spent mostly watching telly rather than career planning, ‘have you thought any more about what you’re going to do?’

Kieron scraped back a dining chair and plonked himself down wearily. ‘Oh God, Mum,’ he stropped. ‘Five minutes you’ve been in and already you’re getting on at me!’

I ruffled his hair and pulled a chair out. My cup of coffee could probably wait. ‘Sorry, love,’ I said. ‘I don’t want to get on at you. I want to help you. Dad and I were only saying this morning, perhaps we could sit down with you this evening – you know – go through some options with you maybe? It’s no good for you, this – sitting around on your own all day, moping. You’ll just get fed up, and you know what you’re like – next thing, you’ll end up getting in a state.’

He shovelled in a couple of mouthfuls before replying. He could eat for Britain could Kieron. ‘I’m not in a state, Mum – I’m just bored. And I don’t mean to snap. It’s just that Jack and James and Si – they’ve got stuff going on, haven’t they? Jack’s got his new job, the others are at college …’ He trailed off, and downed another mouthful. ‘And it’s like … well, it’s like it’s all right for them because they know what they’re doing – and they know because they can all do stuff. But I can’t. I don’t think I can do anything that real grown-ups do. I’m crap at all that.’

‘Nonsense!’ I said firmly. It was a familiar refrain lately. As soon as he thought about the change inherent in making such big decisions, he took the safer route – putting it off for another day. ‘Kieron,’ I told him, ‘you are not “crap”, and of course you can do things.’

He could, too. Though his GCSE results had disappointed him, being mostly Ds, it wasn’t as straightforward as it might have been. He’d struggled with dyslexia since primary school and his diagnosis of Asperger’s had only come in the last two years, meaning valuable time and support that could have helped him achieve higher grades hadn’t been available to him till much later in his school life. That he was capable of more wasn’t in doubt – the teachers had all said so. I reiterated that fact again now. ‘You can do anything you set your mind to,’ I told him. ‘You just have to decide what it is you want to do, that’s all. And that’s what you have to put your mind to – deciding – not avoiding. Which is why you and Dad and I need to sit down and have a proper talk. Anyway, right now I’m off upstairs to change and have a shower before they’re back. And make sure you put that plate back when you’re done, okay? Okay?’

‘Um, oh, yeah. Will do,’ he said, having, in typical teenage boy fashion, already tuned me out in favour of the bit of programme he could still see through the glass doors between the table and the telly.

Honestly, I thought to myself as I headed up the stairs, if anyone had told me when they were little that I’d be worrying about my kids so much at this age, I’d have thought they were mad. But of course, I’d been wrong – older didn’t necessarily mean less difficult to parent. It was just that you did your worrying on a different level.

But at least Kieron could communicate his worries – well, up to a point and after a fashion anyway. I thought back to the anxious-looking little girl who’d be joining my class the following morning. How could she be helped in her troubles – and she clearly had some troubles on her shoulder – if she couldn’t communicate anything to anyone?

Chapter 4

I was feeling lighter of heart as I walked into school the following morning, at least where Kieron was concerned. Where I had only prompted mild teenage disgruntlement, Mike had produced progress, and we’d all gone to bed with a plan that seemed workable – for Kieron to at least think about exploring the possibility of applying to the local college to do a two-year course in Media Studies, with an emphasis on music production.

It had been a friend of Mike’s from work that had suggested it. His son had just finished one and had really enjoyed it, and, better still, it had clearly served him well. He was now doing an apprenticeship with a theatre group in London, learning how to produce music for shows.

Mike had done a soft-sell on it, knowing that to go in guns blazing would be likely to make Kieron anxious by default. Instead, he couched it in terms that made it sound more like a hobby he could dabble in than an actual college course. After all, he loved music as much as he loved football and superheroes (i.e. a lot), and once we looked into things further and found the teaching style was mostly small-group based, it began to seem much less daunting than he’d originally thought. He was still reticent, but he was also asking questions, at least, which was an encouraging development. But now came the biggie: his task for today was to take the bold and scary step of phoning the admissions office to try and make an appointment.

Whether he’d have managed it by the time I got home from work remained to be seen. I felt hopeful, though, and able to turn my attention to the probably equally scared young girl who was joining us today.

I could see Imogen and her grandmother when I walked into reception. They were seated in the corner, on the small sofa that was stationed there for the purpose, and both silently watched my progress through the double doors.

I was pleased to see they’d arrived early as it would be much less daunting for Imogen if she could come straight to my classroom with me than run the gamut of all the other kids arriving.

I raised an arm and waved. ‘Morning!’ I called to them, smiling. They both stood as I approached, as if to attention.

Mrs Hinchcliffe was holding Imogen’s arm protectively, but it was clear she was keen to be gone. ‘Do I have to stay with her?’ she asked me, having acknowledged my greeting.

I shook my head. ‘No, no, that’s fine,’ I told her. ‘Imogen can come with me now.’ I turned and met her gaze. ‘Okay? And will you be picking Imogen up again?’ I asked Mrs Hinchcliffe, ‘or will she be making her own way home?’

Imogen’s grandmother shuffled, a touch uncomfortably, I thought, before she answered. ‘No,’ she said, finally. ‘She knows her way home. It’s only five minutes away. And she won’t want me here, I’m sure. Showing her up …’

Now it was my turn to feel uncomfortable. It really did feel odd to be talking about this girl as if she was an inanimate object. ‘Okay, then,’ I said. ‘Well, we’ll be off then, shall we, Imogen? And I’ll see you, well … whenever, Mrs Hinchcliffe. Though it occurred to me that perhaps we could speak on the phone later – have a bit of a catch-up? If that’s all right.’

She seemed a little surprised at my suggestion, but said that, yes, it would be fine, then headed back out into the warm autumn sunshine, throwing a ‘Be good, Imogen’ back towards us by way of a goodbye.

I’d already decided to skip my usual half-hour in the staffroom and as we were in school so early – there were still ten minutes to go till the bell went – take the opportunity to acclimatise Imogen to her new surroundings before the other children all came crashing in.

‘Come on,’ I told her now, beckoning her towards the doors to the main corridor. ‘Follow me.’

She seemed reluctant to make eye contact, but fell into step with me, chin very firmly on chest. But not before I could see the strange blank expression that had now taken over her face. It really was mask-like; as if, now Nan had gone, a shutter had come down. It made the silence between us feel even more uncomfortable.

I chatted as we walked, trying to fill it. I told her about my own children, and how I would have been in school before her and her Nan were, had it not been for my daughter Riley and her scattiness in the mornings and how this particular morning she’d had us all in a spin, rushing around trying to find her a pair of her ‘stupid’ tights. I kept glancing at Imogen as I spoke, but it wasn’t clear that she was even listening, since there was no response at all.

‘There are going to be five other children joining us in a bit,’ I went on. ‘Three boys, two other girls – and they’re all looking forward to meeting you. I think you’ll like them – particularly the girls, Molly and Shona. They’re a little younger than you – Shona’s in year 8 but Molly’s still in year 7 – and they’re both lovely girls.’

The walk wasn’t a long one, but it seemed so. It was a strange business, inanely chirping away to a girl who seemed not to want to listen or respond. And I wondered – what was going through her head right now? Still, my research had told me that this was the right thing to do – just keep on talking, even if it was into a void. And that, I thought, as we reached my classroom, I was good at.

‘Here we are!’ I said, as we approached the door. ‘My little kingdom!’

It was something to see, too – a proper work of art. In contrast to every other classroom door in the school, mine was highly decorated; covered, top to bottom, in daffodils and daisies, all painted by various children who had passed through it and all cut out and covered in sticky-back plastic, in traditional Blue Peter style. A work of art in its own right, everyone in school commented on it, and I was pleased to see it prompt a reaction. No, not in words, but Imogen did seem to do a bit of a double-take on seeing it.

‘We’ll have to get you to paint a flower for it, too, eh?’ I told her as I unlocked it. I laughed. ‘I think there’s just about room!’

Again, there was almost nothing in the way of a response, and it was an equally odd business trying to do my usual welcome spiel. I ushered Imogen to a seat, and as I proceeded to point out the various aspects of the classroom I felt increasingly like an air hostess – one who was trying to keep the attention of my single indifferent passenger, who only glanced up occasionally and apparently indifferently.

‘And that door there,’ I said, once I’d run through all the basic whats and wheres, ‘is the emergency exit, as you can see, but we often take a table or two out there if the weather is nice. Might do today, in fact. We’ll see …’

It was hard work, but just as I was wondering if I should next show her the brace position, I was rescued by the arrival of Henry.

‘Morning, Miss!’ he said brightly, grinning widely at the pair of us.

‘I’m Henry,’ he told Imogen with a confident can-do air. ‘I came in early so I could check you were here. What’s your name again?’

Meeting his eye now, Imogen seemed to physically shrink. Down went the head onto the chest, too.

‘Her name is Imogen,’ I reminded him. ‘Imogen, Henry is our oldest. In fact he’s your age, and he kind of helps me out, don’t you, Henry? With some of the younger ones.’

I watched Henry swell with pride. ‘Yeah, I do,’ he confirmed. ‘I make sure they don’t mess about too much for Miss. An’ I told them they gotta be all right with you, too. So they will be, okay?’

There was no response to this from Imogen, so I supplied one for her. ‘Thanks, Henry,’ I told him. ‘And you’re right. I’m sure they will be. Now, shall we get some drinks made before the others get here?’

Henry moved towards my little corner and grabbed the kettle so he could fill it for me. I was so impressed with him; was this the same boy who was an inch from exclusion? Maybe stewarding Imogen would be really good for him. ‘Hot chocolate?’ I asked Imogen. ‘That’s how we tend to start the day here. With a nice cup of hot chocolate and a biscuit.’

She glanced up and I noticed her gaze flutter up towards me. And was I mistaken or was that the trace of a smile? It was something, at any rate. Something we could build on. Perhaps we might be able to communicate after all. Right now, though, I took it as evidence that she would indeed like a hot chocolate, so I joined Henry and set about arranging all the plastic cups, plus my mug, ready for my next cup of coffee.

I’d done well with my hot-chocolate stash, which I’d shamelessly blagged not long after I’d arrived in the school. There was a drinks vending machine in the sixth-form block, and a man came every month to fill it, and one day, by chance, we’d met along one of the corridors and had fallen into conversation. I’d told him about how several of my kids came into school hungry and thirsty, and he’d told me about how a small proportion of the drinks had torn sleeves and couldn’t go into the machines he serviced. They were usually thrown away, too. Would I like them?

It was a match made in heaven. I got a new supply of hot chocolate once a month, and he got a free cup of tea before he left and, more often than not, a biscuit as well.

It was a full ten minutes before the other kids arrived, and they were long ones, Imogen silently sipping her drink and Henry sneaking peeks at her as he did likewise. After his initial chattiness he didn’t seem to know quite what to do now, and kept glancing towards the door, hoping for reinforcements. I think we were both relieved when a rumble in the corridor bore fruit and the other four kids came bowling in, Shona and Molly arm in arm as per usual, and Ben and Gavin doing their usual pushing and shoving.

‘Ah,’ I said, ‘here’s the rest of our little group, Imogen. Right,’ I told them, ‘come on in and take your seats everyone, and let’s get this party started.’

I made quick introductions as I prepared chocolate for the rest, and told the girls to go and sit at Imogen’s table. Today, with even numbers, we’d have a boys’ group and a girls’ group – for this morning’s activity, at any rate. I also got out the biscuits, eyeing Ben as I always did. Ben, I knew, was one of the kids who never got breakfast, as his dad worked shifts and would be asleep when he’d left for school. I’d once asked him if he could maybe grab some toast to see him through, but his response was that there wasn’t often any bread.

I couldn’t think of Ben without feeling a sharp pang of sympathy, and today was no different. I glanced at him now, yawning away, looking as if he’d just tumbled out of bed fully clothed. His off-white shirt, unironed and crumpled, had its two bottom buttons missing, and was only half tucked into his grubby school trousers. He didn’t have a school jumper, and when I’d asked him about that he’d told me it was because his dad didn’t think it was worth spending the money as he’d probably be excluded soon and would be off to a different school.

‘You can have one of my spares,’ I’d said, this being the logical solution, but Ben, loyal to the last, and not wanting charity, shook his head. ‘Thanks, Miss,’ he’d said. ‘But if my dad don’t want me to have one then I won’t have one.’

Free biscuits, however, were another matter – no one in my classroom ever seemed to turn them down and, though I could see Molly was embarrassed, listening to Shona trying to engage Imogen in conversation – she was blushing furiously – the atmosphere in the room wasn’t quite as awkward as I’d feared.

And my plan for the morning would hopefully encourage that further.

‘Right,’ I said, once everyone had a drink and a biscuit. ‘Chatter time is over. Time to listen.’

I handed out two packets of dried spaghetti and two bags of marshmallows, to the general appreciation of all concerned.

‘Wobbly Towers!’ said Henry as I did so. ‘Yess!’

‘Yes, Wobbly Towers,’ I explained, for the benefit of Imogen and the others – Henry was the only one of the group who’d done the activity before, the other children having only been with me for a month or so. ‘Henry’s correct,’ I said. ‘That’s what we’re doing this morning. And today it’s going to be boys against girls.’

I then went on to explain the basics of ‘Wobbly Towers’, one of my most popular and well-used group activities. I would give the children an hour, during which they had to spend half an hour designing and planning the structure of a wobbly tower, and then build one out of the sticks of dried spaghetti and the marshmallows. It was a little bit like creating the molecular structure models you’d see in science classes, but we made no mention of atoms and bonds or anything complex like that. They simply had to create something that would stand unsupported for at least one minute, with a prize going to the team who, in my ‘professional’ opinion, had been the most inventive with their construction ideas.

Wobbly Towers was a team activity, which meant it was also a great ice-breaker, which was why I did it so often. With children coming and going all the time it was important to plan activities that helped with the bonding process; especially important, given that the kids that came to me often did so because of their struggles to find friends.

Henry’s hand shot up as soon as I’d finished speaking.

‘Yes, Henry?’ I said, one eye on Imogen’s impassive face.

‘Miss, do we get to eat the marshmallows after we’ve finished?’

‘Hmm, let me think …’ I said, pretending to muse as I went to my desk to get paper and pencils for everyone. ‘Well, if you take the full half hour to plan properly (the kids were always itching to plunge in impulsively and start building, so that was important) and if you do create a tower that stays upright for the whole minute … then, yes, I suppose I could let you share the marshmallows out at the end.’

There were smiles all round. We had the same conversation, pretty much, every time we did it.

‘Epic,’ said Henry to his fellow boys, as they took the pieces of paper I was proffering. ‘Let’s show the girls, eh?’

Molly and Shona tutted as they came up behind them, Imogen falling into step behind Shona, and taking the paper and pencil she passed back to her.

‘There we are,’ Shona said to her. ‘Just put your name at the top, seeing as how you don’t like to talk. And Molly and me will tell you what you’ve got to write on it. Oh, and yes –’ She turned to me. ‘Miss, can I have another bit of paper? There,’ she said, as I passed her another and she handed it over to Imogen. ‘You can use that bit of paper to tell us stuff, can’t you? It’ll be like when I had tonsillitis and I lost my voice all day. I had to write everything down then, too.’

Nice one, Shona! I thought, as the children began to settle to their planning. What a clever, intuitive, emotionally intelligent girl she was. She would be okay, would Shona, I decided. Her late parents would have been so proud of her.

Which got me to thinking – what was the situation with Imogen’s exactly? With the dad? The second wife? And where exactly was her mum? What precisely was the root of her current troubling situation? I would find out more about the family at some point, I imagined. But in the meantime, as of today, I was on a mission.

If there was no physical reason for Imogen’s silence – and it seemed there wasn’t – then my own mission, I decided, as the children set about their engineering one, was to find a way to get her to speak. To me.

Chapter 5

Leaving the children occupied with their exciting engineering activity left me freed up to do a little more research. I’d already looked up the basics of selective mutism on the internet, and everything I’d discovered so far had told me pretty much the same thing: that children with the condition ‘opted out’ of speaking in social situations – of which school was an obvious example. Most of the time, however, they spoke completely normally in close family environments, when no one else was listening – as in at home.

I wasn’t sure about that key phrase ‘opt out’, though. It seemed to me – again, reading the research I had come across – that it wasn’t a case of a child ‘opting’ not to speak, but rather of them literally being unable to do so. In fact, another thing I learned was that children found it so distressing that they would actively avoid situations which would bring on their mutism. And, unfortunately, you couldn’t avoid school.

But where had it come from? In Imogen’s case, what had been the trigger? That there had been one didn’t seem to be in doubt. So it was a case of going back, then – back in time to look at the history. Because if I could tease out what had caused it, I had the best tool to help her. Without knowing it, we wouldn’t be addressing the problem – only the symptoms. Simple logic, but it seemed the best place to start.