Полная версия

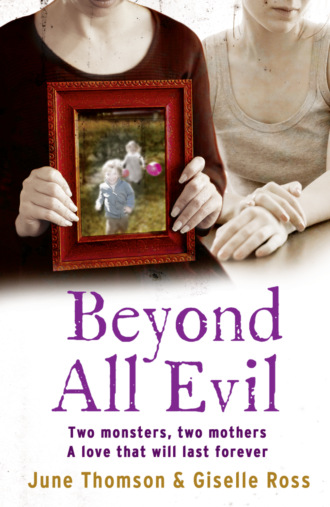

Beyond All Evil: Two monsters, two mothers, a love that will last forever

What had the world to offer me that I could not find at home?

June: You were so fortunate. If my mum couldn’t love me, how could anyone else?

Mum had cleared at arguably the most vulnerable time in the life of a teenage girl.

I was sad, deeply sad, but I tried to hide it behind a mask of indifference and bravado. A mother’s love should be the rock upon which each of our lives is built, but in my case it wasn’t to be the case.

Did my mother not love me enough to stay? If she had loved me why would she leave me? Perhaps I’m being too harsh, but I could not help how I felt then, and I can’t help how I feel now.

I’m certain she must have loved me in her own way – or is that just something I comfort myself with? I still don’t know. What I do know is that from that moment I knew I couldn’t rely on her.

Her leaving had dredged up many emotions which I now realised had been experienced subconsciously. Even when she was in my life, I did not feel the closeness with her that I had with my father.

I had been able to identify with my pals’ closeness to their own fathers because that was my experience. I never doubted for a single second that Dad loved me. Our closeness was a living thing and it remains so. I have no idea what the catalyst was for Mum leaving us for good. I wouldn’t see her for many years and then I would learn that she had eventually met someone else.

Mum and Dad had very different personalities and it was a period when ordinary couples were not expected to be openly affectionate towards each other. So there had been no real tell-tale signs indicating her impending departure. One day she was there, the next she was gone.

To this day, Dad will still not say a bad word about her, but I have always had the impression that he was secretly relieved when she left.

It must have been very difficult for him but he was armoured by his reputation for being a good and decent man. He was held in such high esteem and so well liked in the community that no one dared gossip about the breakdown of his marriage.

Dad was a foreman at the local dye works and he continued to work in the factory and function as father and mother to us all. In those days, in those circumstances, no one would have raised an eyebrow if Jim Martin had decided to deliver his children into the care of social workers. In fact, this was commonplace when a working man was deserted by his wife.

He was, however, made of sterner stuff. It must have been hard for him in a town such as Kilbirnie, in Ayrshire, a grim, grey industrial place that produced a similar breed of people.

Dad did not whine. He just did the best he could and his best was very good.

Ironically, I would repay him by going off the rails.

Giselle: Wherever I turned, wherever I looked, Ma and Da were always there …

The words written in my final school report card declared that Giselle Ross had grown into an amenable young woman who might do well in the world if she would just ‘push herself forward a bit more’.

Fat chance. I had no wish to push myself forward, or to trek too far into the world beyond the confines of my home and family. The word ‘confine’ conjures up a sense of being restricted. I wasn’t. I embraced the safety of home life. I harboured no ambition for a high-powered executive career. Was that wrong of me? Maybe. But I was being true to myself. One must never confuse contentment with a lack of ambition.

Teenage love affairs were mysteries to be experienced by others. I had never had a boyfriend. I was – and I remained for a long time – an innocent. My days revolved around the home, like a wheel that turned contentedly through one day to the next. Ma and Da were the hub, my brothers and sisters the spokes of the wheel. I had no notion of becoming a mother, but Ma demanded that her house be ‘filled with babies’, and in time it would. I would then become a brilliant auntie to the children in this ever-extending family.

When Katie had her two children, Paul and little Giselle, I drew them into my loving world. I saw them every day. I was like a second mother to them, as Katie would become a second mother to my Paul and little Jay-Jay when they came along.

From time to time, Ma and Da would, to coin a phrase, make efforts to persuade me to get a life. I had a life, a wonderful life, and one that satisfied all of my needs. I felt no jealousy of others who lived a different kind of life.

And so it would go on.

June: You were the perfect daughter; I was acting like a brat …

I wasn’t so much bad as wilful, an attention-seeker. These days psychologists would have a name for it and I’m sure they could come up with any number of reasons to explain why I began acting out. It doesn’t take a degree in psychology to recognise that the change in my behaviour coincided with abandonment and a flood of teenage hormones. I may have been secretly relieved that Mum was out of our lives but it did leave a huge void.

Afterwards, I felt as if I were searching, always searching, for something or someone to fill the emptiness. I pushed back the boundaries – pinching and drinking vodka from Dad’s cupboard; staying out late; running away from home. All stupid stuff, really. I just yearned to be noticed, to be valued; for someone to put their arms around me and assure me that I was safe. In the aftermath of my misdemeanours, my granny was drafted in to bring me back to my senses. She was a lovely old woman with a particularly simplistic view of the universe, which, as far as she was concerned, was painted in black and white.

She would declare, ‘Just remember, June, once you’ve made your bed you have to lie on it – think of what you’re doing to yourself and your dad.’

Poor Dad. He was so busy with work and looking after the home that the only way – in my confused mind – that I could get his full attention was by getting into bother. I can still remember the weary conversations, the pained expressions on his face.

‘Why are you doing this, June?’ he would say in an exasperated tone of voice, in reference to my latest escapade. ‘Why can’t you just behave like everyone else?’ he would go on.

Dad could not fathom why I was playing truant constantly and getting into daft scrapes. In retrospect, it is almost as if I was being ‘bad’ to test his love, trying to establish how far I could push him before he, too, abandoned me.

‘I can’t,’ I would reply, without knowing why, my face set in a perpetual scowl. His hurt looks wounded me to the core, but I could not help myself.

One of the worst things I did to him was to run away from home. I decided I would hitchhike to London. I set off with two pals, not giving a second thought to the pain it would cause him. When it was discovered that we were gone, he had everyone out looking for us: friends, relatives, the police. Our big adventure was, of course, doomed to failure. We actually made it south of the border but it wasn’t long before we ran out of money and were forced to throw ourselves on the mercy of the police. We were returned home in disgrace by social workers.

Dad was mortified and he lambasted me. Did I know the trouble I had caused? Did I realise how worried he had been? What kind of example was I to my brothers and sister? I stood, head bowed, stung by his words – but for some inexplicable reason a part of me was pleased to be the centre of attention.

I would never again run away from Dad, but it would take me a long time to shake off my recalcitrance. If someone said, ‘Don’t do that, June,’ that is precisely what I would do. What I needed was to be truly loved, to find someone of my own, someone who would make me the centre of his whole world. I would find him. Desperation shines like a beacon, and so often a light in the darkness attracts a predator.

His name was Rab Thomson.

Giselle: As time passed, we were walking to the same destination – but from different starting points …

The woman in the mirror was far less vulnerable than the girl had been. I swept the brush through my gleaming red hair. Ma had been right. The hair I had hated so much as a teenager had become my crowning glory.

It had been a long time since I had first stood in front of this looking-glass, bemoaning my perceived imperfections. I still did not care much for what I saw, but I was safe, perennially cloistered by invisible walls that had been built over so many years by my loving family. My brothers and sisters had long since gone, creating new lives of their own outwith the fortress. I remained. My ‘job’ was still to look after my parents.

My mother’s health had deteriorated badly. She suffered from chronic asthma, which obviously affected her breathing. It was extremely debilitating. She would spend nights in the living room, sleeping in a chair, propped up by pillows. I was never far away. I delighted in being able to look after her – and Da – as they had looked after all of us. I still had no sense that I was sacrificing myself and I had long since come to terms with my detachment from the ‘real’ world. It was a price worth paying. I was content. I saw the good in people, rather than the bad. I had learned how to do that from Ma. She helped her neighbours. She would not pass a beggar without giving him money. She bought sweets for children who had none.

When we were young, Ma and Da would take us on trips, days out in the car, walks in the countryside, strolls along seaside promenades. It was my turn now to chaperone them. I loved them. I loved their safe world. I embraced it. I never wanted to leave it. It might have remained so until one day, at the age of 32, I walked into our local post office with Ma. The man standing behind the polished wooden counter had soft brown eyes and he smiled at me.

His name was Ashok Kalyanjee.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.