полная версия

полная версияAutobiography of Benjamin Franklin

You ask what I mean? You love stories, and will excuse my telling one of myself.

When I was a child of seven year old, my friends, on a holiday, filled my pocket with coppers. I went directly to a shop where they sold toys for children; and being charmed with the sound of a whistle, that I met by the way in the hands of another boy, I voluntarily offered and gave all my money for one. I then came home, and went whistling all over the house, much pleased with my whistle, but disturbing all the family. My brothers, and sisters, and cousins, understanding the bargain I had made, told me I had given four times as much for it as it was worth; put me in mind what good things I might have bought with the rest of the money; and laughed at me so much for my folly, that I cried with vexation; and the reflection gave me more chagrin than the whistle gave me pleasure.

This, however, was afterwards of use to me, the impression continuing on my mind; so that often, when I was tempted to buy some unnecessary thing, I said to myself, Don't give too much for the whistle; and I saved my money.

As I grew up, came into the world, and observed the actions of men, I thought I met with many, very many, who gave too much for the whistle.

When I saw one too ambitious of court favor, sacrificing his time in attendance on levees, his repose, his liberty, his virtue, and perhaps his friends, to attain it, I have said to myself, This man gives too much for his whistle.

When I saw another fond of popularity, constantly employing himself in political bustles, neglecting his own affairs, and ruining them by neglect, He pays, indeed, said I, too much for his whistle.

If I knew a miser who gave up every kind of comfortable living, all the pleasure of doing good to others, all the esteem of his fellow citizens, and the joys of benevolent friendship, for the sake of accumulating wealth, Poor man, said I, you pay too much for your whistle.

When I met with a man of pleasure, sacrificing every laudable improvement of the mind, or of his fortune, to mere corporeal sensations, and ruining his health in their pursuit, Mistaken man, said I, you are providing pain for yourself, instead of pleasure; you give too much for your whistle.

If I see one fond of appearance, or fine clothes, fine houses, fine furniture, fine equipages, all above his fortune, for which he contracts debts, and ends his career in a prison, Alas! say I, he has paid dear, very dear, for his whistle.

When I see a beautiful, sweet-tempered girl married to an ill-natured brute of a husband, What a pity, say I, that she should pay so much for a whistle!

In short, I conceive that great part of the miseries of mankind are brought upon them by the false estimates they have made of the value of things, and by their giving too much for their whistles.

Yet I ought to have charity for these unhappy people, when I consider, that, with all this wisdom of which I am boasting, there are certain things in the world so tempting, for example, the apples of King John, which happily are not to be bought; for if they were put to sale by auction, I might very easily be led to ruin myself in the purchase, and find that I had once more given too much for the whistle.

Adieu, my dear friend, and believe me ever yours very sincerely and with unalterable affection,

B. Franklin.A LETTER TO SAMUEL MATHER

Passy, May 12, 1784.Revd Sir,

It is now more than 60 years since I left Boston, but I remember well both your father and grandfather, having heard them both in the pulpit, and seen them in their houses. The last time I saw your father was in the beginning of 1724, when I visited him after my first trip to Pennsylvania. He received me in his library, and on my taking leave showed me a shorter way out of the house through a narrow passage, which was crossed by a beam overhead. We were still talking as I withdrew, he accompanying me behind, and I turning partly towards him, when he said hastily, "Stoop, stoop!" I did not understand him, till I felt my head hit against the beam. He was a man that never missed any occasion of giving instruction, and upon this he said to me, "You are young, and have the world before you; stoop as you go through it, and you will miss many hard thumps." This advice, thus beat into my head, has frequently been of use to me; and I often think of it, when I see pride mortified, and misfortunes brought upon people by their carrying their heads too high.

B. Franklin.THE ENDBIBLIOGRAPHY

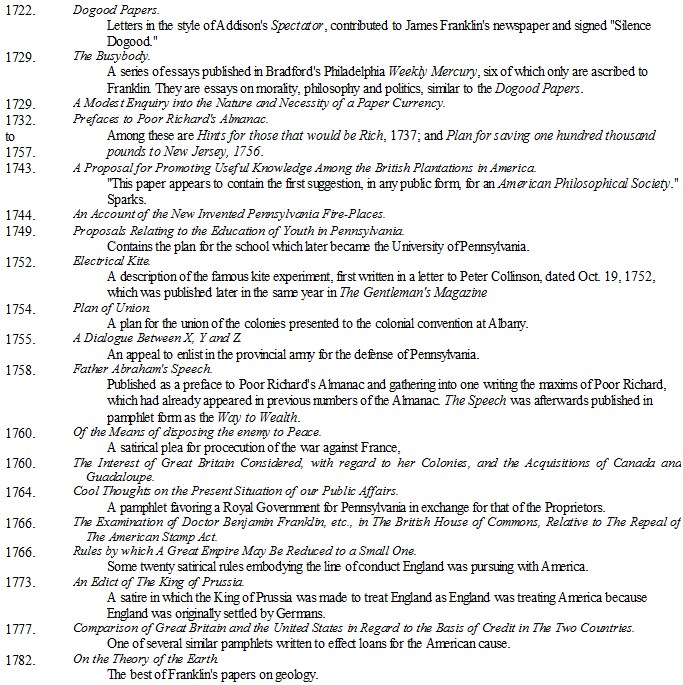

The last and most complete edition of Franklin's works is that by the late Professor Albert H. Smyth, published in ten volumes by the Macmillan Company, New York, under the title, The Writings of Benjamin Franklin. The other standard edition is the Works of Benjamin Franklin by John Bigelow (New York, 1887). Mr. Bigelow's first edition of the Autobiography in one volume was published by the J. B. Lippincott Company of Philadelphia in 1868. The life of Franklin as a writer is well treated by J. B. McMaster in a volume of The American Men of Letters Series; his life as a statesman and diplomat, by J. T. Morse, American Statesmen Series, one volume; Houghton, Mifflin Company publish both books. A more exhaustive account of the life and times of Franklin may be found in James Parton's Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin (2 vols., New York, 1864). Paul Leicester Ford's The Many-Sided Franklin is a most chatty and readable book, replete with anecdotes and excellently and fully illustrated. An excellent criticism by Woodrow Wilson introduces an edition of the Autobiography in The Century Classics (Century Co., New York, 1901). Interesting magazine articles are those of E. E. Hale, Christian Examiner, lxxi, 447; W. P. Trent, McClure's Magazine, viii, 273; John Hay, The Century Magazine, lxxi, 447.

See also the histories of American literature by C. F. Richardson, Moses Coit Tyler, Brander Matthews, John Nichol, and Barrett Wendell, as well as the various encyclopedias. An excellent bibliography of Franklin is that of Paul Leicester Ford, entitled A List of Books Written by, or Relating to Benjamin Franklin (New York, 1889).

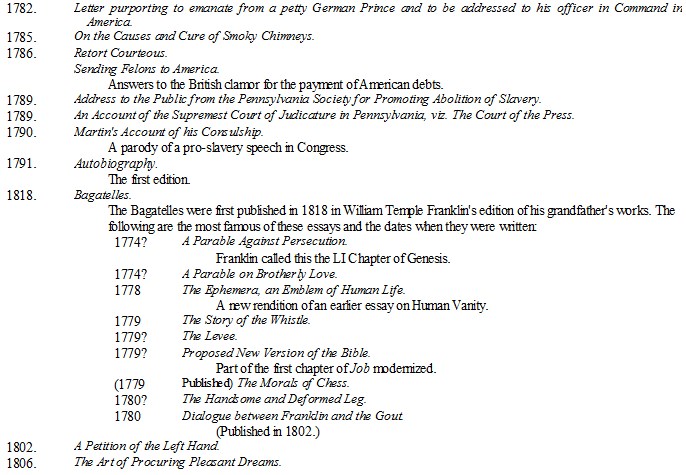

The following list of Franklin's works contains the more interesting publications, together with the dates of first issue.

MEDAL GIVEN BY THE BOSTON PUBLIC SCHOOLS FROM THE FRANKLIN FUND

1

The Many-Sided Franklin. Paul L. Ford.

2

For the division into chapters and the chapter titles, however, the present editor is responsible.

3

A small village not far from Winchester in Hampshire, southern England. Here was the country seat of the Bishop of St. Asaph, Dr. Jonathan Shipley, the "good Bishop," as Dr. Franklin used to style him. Their relations were intimate and confidential. In his pulpit, and in the House of Lords, as well as in society, the bishop always opposed the harsh measures of the Crown toward the Colonies.—Bigelow.

4

In this connection Woodrow Wilson says, "And yet the surprising and delightful thing about this book (the Autobiography) is that, take it all in all, it has not the low tone of conceit, but is a staunch man's sober and unaffected assessment of himself and the circumstances of his career."

5

See Introduction.

6

A small landowner.

7

January 17, new style. This change in the calendar was made in 1582 by Pope Gregory XIII, and adopted in England in 1752. Every year whose number in the common reckoning since Christ is not divisible by 4, as well as every year whose number is divisible by 100 but not by 400, shall have 365 days, and all other years shall have 366 days. In the eighteenth century there was a difference of eleven days between the old and the new style of reckoning, which the English Parliament canceled by making the 3rd of September, 1752, the 14th. The Julian calendar, or "old style," is still retained in Russia and Greece, whose dates consequently are now 13 days behind those of other Christian countries.

8

The specimen is not in the manuscript of the Autobiography.

9

Secret gatherings of dissenters from the established Church.

10

Franklin was born on Sunday, January 6, old style, 1706, in a house on Milk Street, opposite the Old South Meeting House, where he was baptized on the day of his birth, during a snowstorm. The house where he was born was burned in 1810.—Griffin.

11

Cotton Mather (1663-1728), clergyman, author, and scholar. Pastor of the North Church, Boston. He took an active part in the persecution of witchcraft.

12

Nantucket.

13

Tenth.

14

System of short-hand.

15

This marble having decayed, the citizens of Boston in 1827 erected in its place a granite obelisk, twenty-one feet high, bearing the original inscription quoted in the text and another explaining the erection of the monument.

16

Small books, sold by chapmen or peddlers.

17

Grub-street: famous in English literature as the home of poor writers.

18

A daily London journal, comprising satirical essays on social subjects, published by Addison and Steele in 1711-1712. The Spectator and its predecessor, the Tatler (1709), marked the beginning of periodical literature.

19

John Locke (1632-1704), a celebrated English philosopher, founder of the so-called "common-sense" school of philosophers. He drew up a constitution for the colonists of Carolina.

20

A noted society of scholarly and devout men occupying the abbey of Port Royal near Paris, who published learned works, among them the one here referred to, better known as the Port Royal Logic.

21

Socrates confuted his opponents in argument by asking questions so skillfully devised that the answers would confirm the questioner's position or show the error of the opponent.

22

Alexander Pope (1688-1744), the greatest English poet of the first half of the eighteenth century.

23

Franklin's memory does not serve him correctly here. The Courant was really the fifth newspaper established in America, although generally called the fourth, because the first, Public Occurrences, published in Boston in 1690, was suppressed after the first issue. Following is the order in which the other four papers were published: Boston News Letter, 1704; Boston Gazette, December 21, 1719; The American Weekly Mercury, Philadelphia, December 22, 1719; The New England Courant, 1721.

24

Disclosed.

25

Kill van Kull, the channel separating Staten Island from New Jersey on the north.

26

Samuel Richardson, the father of the English novel, wrote Pamela, Clarissa Harlowe, and the History of Sir Charles Grandison, novels published in the form of letters.

27

Manuscript.

28

The frames for holding type are in two sections, the upper for capitals and the lower for small letters.

29

Protestants of the South of France, who became fanatical under the persecutions of Louis XIV, and thought they had the gift of prophecy. They had as mottoes "No Taxes" and "Liberty of Conscience."

30

Temple Franklin considered this specific figure vulgar and changed it to "stared with astonishment."

31

Pennsylvania and Delaware.

32

A peep-show in a box.

33

There were no mints in the colonies, so the metal money was of foreign coinage and not nearly so common as paper money, which was printed in large quantities in America, even in small denominations.

34

Spanish dollar about equivalent to our dollar.

35

"In one of the later editions of the Dunciad occur the following lines:

'Silence, ye wolves! while Ralph to Cynthia howls,And makes night hideous—answer him, ye owls.'To this the poet adds the following note:

'James Ralph, a name inserted after the first editions, not known till he writ a swearing-piece called Sawney, very abusive of Dr. Swift, Mr. Gay, and myself.'"

36

One of the oldest parts of London, north of St. Paul's Cathedral, called "Little Britain" because the Dukes of Brittany used to live there. See the essay entitled "Little Britain" in Washington Irving's Sketch Book.

37

A gold coin worth about four dollars in our money.

38

A popular comedian, manager of Drury Lane Theater.

39

Street north of St. Paul's, occupied by publishing houses.

40

Law schools and lawyers' residences situated southwest of St. Paul's, between Fleet Street and the Thames.

41

Edward Young (1681-1765), an English poet. See his satires, Vol. III, Epist. ii, page 70.

42

The printing press at which Franklin worked is preserved in the Patent Office at Washington.

43

Franklin now left the work of operating the printing presses, which was largely a matter of manual labor, and began setting type, which required more skill and intelligence.

44

A printing house is called a chapel because Caxton, the first English printer, did his printing in a chapel connected with Westminster Abbey.

45

A holiday taken to prolong the dissipation of Saturday's wages.

46

The story is that she met Christ on His way to crucifixion and offered Him her handkerchief to wipe the blood from His face, after which the handkerchief always bore the image of Christ's bleeding face.

47

James Salter, a former servant of Hans Sloane, lived in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. "His house, a barber-shop, was known as 'Don Saltero's Coffee-House.' The curiosities were in glass cases and constituted an amazing and motley collection—a petrified crab from China, a 'lignified hog,' Job's tears, Madagascar lances, William the Conqueror's flaming sword, and Henry the Eighth's coat of mail."—Smyth.

48

About three miles.

49

About $167.

50

"Not found in the manuscript journal, which was left among Franklin's papers."—Bigelow.

51

A crimp was the agent of a shipping company. Crimps were sometimes employed to decoy men into such service as is here mentioned.

52

The creed of an eighteenth century theological sect which, while believing in God, refused to credit the possibility of miracles and to acknowledge the validity of revelation.

53

A great English poet, dramatist, and critic (1631-1700). The lines are inaccurately quoted from Dryden's Œdipus, Act III, Scene I, line 293.

54

A Spanish term meaning a combination for political intrigue; here a club or society.

55

A sheet 8-1/2 by 13-1/2 inches, having the words pro patria in translucent letters in the body of the paper. Pica—a size of type; as, A B C D: Long Primer—a smaller size of type; as, A B C D.

56

To arrange and lock up pages or columns of type in a rectangular iron frame, ready for printing.

57

Reduced to complete disorder.

58

I got his son once £500.—Marg. note.

59

Recalled to be redeemed.

60

This part of Philadelphia is now the center of the wholesale business district.

61

Paper money is a promise to pay its face value in gold or silver. When a state or nation issues more such promises than there is a likelihood of its being able to redeem, the paper representing the promises depreciates in value. Before the success of the Colonies in the Revolution was assured, it took hundreds of dollars of their paper money to buy a pair of boots.

62

Mrs. Franklin survived her marriage over forty years. Franklin's correspondence abounds with evidence that their union was a happy one. "We are grown old together, and if she has any faults, I am so used to them that I don't perceive them." The following is a stanza from one of Franklin's own songs written for the Junto:

"Of their Chloes and Phyllises poets may prate,I sing my plain country Joan,These twelve years my wife, still the joy of my life,Blest day that I made her my own."63

Here the first part of the Autobiography, written at Twyford in 1771, ends. The second part, which follows, was written at Passy in 1784.

64

After this memorandum, Franklin inserted letters from Abel James and Benjamin Vaughan, urging him to continue his Autobiography.

65

Franklin expressed a different view about the duty of attending church later.

66

Compare Philippians iv, 8.

67

A famous Greek philosopher, who lived about 582-500 B. C. The Golden Verses here ascribed to him are probably of later origin. "The time which he recommends for this work is about even or bed-time, that we may conclude the action of the day with the judgment of conscience, making the examination of our conversation an evening song to God."

68

This "little book" is dated July 1, 1733.—W. T. F.

69

"O philosophy, guide of life! O searcher out of virtue and exterminator of vice! One day spent well and in accordance with thy precepts is worth an immortality of sin."—Tusculan Inquiries, Book V.

70

Professor McMaster tells us that when Franklin was American Agent in France, his lack of business order was a source of annoyance to his colleagues and friends. "Strangers who came to see him were amazed to behold papers of the greatest importance scattered in the most careless way over the table and floor."

71

While there can be no question that Franklin's moral improvement and happiness were due to the practice of these virtues, yet most people will agree that we shall have to go back of his plan for the impelling motive to a virtuous life. Franklin's own suggestion that the scheme smacks of "foppery in morals" seems justified. Woodrow Wilson well puts it: "Men do not take fire from such thoughts, unless something deeper, which is missing here, shine through them. What may have seemed to the eighteenth century a system of morals seems to us nothing more vital than a collection of the precepts of good sense and sound conduct. What redeems it from pettiness in this book is the scope of power and of usefulness to be seen in Franklin himself, who set these standards up in all seriousness and candor for his own life." See Galatians, chapter V, for the Christian plan of moral perfection.

72

Nothing so likely to make a man's fortune as virtue.—Marg. note.

73

This is a marginal memorandum.—B.

74

The almanac at that time was a kind of periodical as well as a guide to natural phenomena and the weather. Franklin took his title from Poor Robin, a famous English almanac, and from Richard Saunders, a well-known almanac publisher. For the maxims of Poor Richard, see pages 331-335.

75

June 23 and July 7, 1730.—Smyth.

76

See "A List of Books written by, or relating to Benjamin Franklin," by Paul Leicester Ford. 1889. p. 15.—Smyth.

77

Dr. James Foster (1697-1753):—

"Let modest Foster, if he will excel

Ten metropolitans in preaching well."

–Pope (Epilogue to the Satires, I, 132).

"Those who had not heard Farinelli sing and Foster preach were not qualified to appear in genteel company," Hawkins. "History of Music."—Smyth.

78

"The authority of Franklin, the most eminently practical man of his age, in favor of reserving the study of the dead languages until the mind has reached a certain maturity, is confirmed by the confession of one of the most eminent scholars of any age.

79

George Whitefield, pronounced Hwit'field (1714-1770), a celebrated English clergyman and pulpit orator, one of the founders of Methodism.

80

A part of the palace of Westminster, now forming the vestibule to the Houses of Parliament in London.

81

Wm. Penn's agents sought recruits for the colony of Pennsylvania in the low countries of Germany, and there are still in eastern Pennsylvania many Germans, inaccurately called Pennsylvania Dutch. Many of them use a Germanized English.

82

James Logan (1674-1751) came to America with William Penn in 1699, and was the business agent for the Penn family. He bequeathed his valuable library, preserved at his country seat, "Senton," to the city of Philadelphia.—Smyth.

83

See the votes.—Marg. note.

84

The Franklin stove is still in use.

85

Warwick Furnace, Chester County, Pennsylvania, across the Schuylkill River from Pottstown.

86

Tench Francis, uncle of Sir Philip Francis, emigrated from England to Maryland, and became attorney for Lord Baltimore. He removed to Philadelphia and was attorney-general of Pennsylvania from 1741 to 1755. He died in Philadelphia August 16, 1758.—Smyth.

87

Later called the University of Pennsylvania.

88

See the votes to have this more correctly.—Marg. note.

89

Gilbert Tennent (1703-1764) came to America with his father, Rev. William Tennent, and taught for a time in the "Log College," from which sprang the College of New Jersey.—Smyth.

90

See votes.

91

Vauxhall Gardens, once a popular and fashionable London resort, situated on the Thames above Lambeth. The Gardens were closed in 1859, but they will always be remembered because of Sir Roger de Coverley's visit to them in the Spectator and from the descriptions in Smollett's Humphry Clinker and Thackeray's Vanity Fair.

![Memoirs of Benjamin Franklin; Written by Himself. [Vol. 2 of 2]](/covers_200/24858395.jpg)