Полная версия

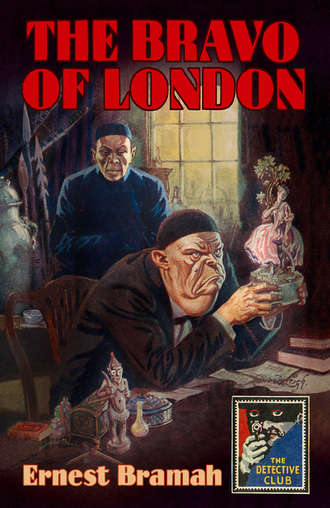

The Bravo of London: And ‘The Bunch of Violets’

‘Fank—“Chilly” Fank,’ he prompted. ‘Now you get me surely?’

‘Never heard the name in my life,’ declared Joolby with no increase of friendliness.

‘Oh, right you are, governor, if you say so,’ accepted Fank, but with the spitefulness of the stinging insect he could not refrain from adding: ‘I don’t suppose I should have been able to imagine you if I hadn’t seen it. Doing anything in this way now?’

‘This,’ freed of its unsavoury covering, was revealed as an uncommonly fine piece of Dresden china. It would have required no particular connoisseurship to recognise that so perfect and delicate a thing might be of almost any value. Joolby, who combined the inspired flair of the natural expert with sundry other anomalous qualities in his distorted composition, did not need to give more than one glance—although that look was professionally frigid.

‘Where did it come from?’ he asked merely.

‘Been in our family for centuries, governor,’ replied Fank glibly, at the same time working in a foxy wink of mutual appreciation; ‘the elder branch of the Fanks, you understand, the Li-ces-ter-shire de Fankses. Oh, all right, sir, if you feel that way’—for Mr Joolby had abruptly dissolved this proposed partnership in humour by pushing the figure aside and putting a hand to his crutches—‘it’s from a house in Grosvenor Crescent.’

‘Tuesday night’s job?’

‘Yes,’ was the reluctant admission.

‘No good to me,’ said the dealer with sharp decision.

‘It’s the real thing, governor,’ pleaded Mr Fank with fawning persuasiveness, ‘or I wouldn’t ask you to make an offer. The late owner thought very highly of it. Had a cabinet all to itself in the drorin’-room there—so I’m told, for of course I had nothing to do with the job personally. Now—’

‘You needn’t tell me whether it’s the real thing or not,’ said Mr Joolby. ‘That’s my look out.’

‘Well then, why not back yer knowledge, sir? It’s bound to pay yer in the end. Say a … well, what, about a couple of … It’s with you, governor.’

‘It’s no good, I tell you,’ reiterated Mr Joolby with seeming indifference. ‘It’s mucher too valuable to be worth anything—unless it can be shown on the counter. Piece like this is known to every big dealer and every likely collector in the land. Offer it to any Tom, Dick or Harry and in ten minutes I might have Scotland Yard nosing about my place like ferrets.’

‘And that would never do, would it, Mr Joolby?’ leered Fank pointedly. ‘Gawd knows what they wouldn’t find here.’

‘They would find nothings wrong because I don’t buy stuff like this that the first numskull brings me. What do you expect me to do with it, fellow? I can’t melt it, or reset it, or cut it up, can I? You might as well bring me the Albert Memorial … Here, take the thing away and drop it in the river.’

‘Oh blimey, governor, it isn’t as bad as all that. What abart America? You did pretty well with those cameos wot come out of that Park Lane flat, I hear.’

‘Eh, what’s that? You say, rascal—’

‘No offence, governor. All I means is you can keep it for a twelvemonth and then get it quietly off to someone at a distance. Plenty of quite respectable collectors out there will be willing to buy it after it’s been pinched for a year.’

‘Well—you can leave it and I’ll see,’ conceded Mr Joolby, to whom Fank’s random shot had evidently suggested a possible opening. ‘At your own risk, mind you. I may be able to sell it for a trifle some day or I may have all my troubles for nothing.’ But just as Chilly Fank was regarding this as satisfactorily settled and wondering how he could best beat up to the next move, the unaccountable dealer seemed to think better—or worse—of it for he pushed the figure from him with every appearance of a final decision. ‘No; I tell you it isn’t worth it. Here, wrap it up again and don’t waste my time. I’d mucher rather not.’

‘That’ll be all right, governor,’ hastily got in Fank, though similar experiences in the past prompted him not to be entirely impressed by a receiver’s methods. ‘I’ll leave it with you anyhow; I know you’ll do the straight thing when it’s planted. And, could you—you don’t mind a bit on account to go on with, do you? I’m not exactly what you’d call up and in just at the moment.’

‘A bit on account, hear him. Come, I like that when I’m having all the troubles and may be out of my pocket in the end. Be off with you, greedy fellow.’

‘Oh rot yer!’ exclaimed Fank, with a sudden flare of passion that at least carried with it the dignity of a genuine emotion; ‘I’ve had just abart enough of you and your blinkin’ game, Toady Joolby. Here, I’d sooner smash the bloody thing, straight, than be such a ruddy mug as to swallow any of your blahsted promises,’ and there being no doubt that Mr Fank for once in a way meant approximately what he said, Joolby had no alternative, since he had every intention of keeping the piece, but to retire as gracefully as possible from his inflexible position.

‘Well, well; we need not lose our tempers, Mr Fank; that isn’t business,’ he said smoothly and without betraying a shadow of resentment. ‘If you are really stoney up—I’m not always very quick at catching the literal meaning of your picturesque expressions—I don’t mind risking—shall we say?—one half a—or no, you shall have a whole Bradbury.’

‘Now you’re talking English, sir,’ declared the mollified Fank (perhaps a little optimistically), ‘but couldn’t you make it a couple? Yer see—well’—as Mr Joolby’s expression gave little indication of rising to this suggestion—‘one and a thin ’un anyway.’

‘Twenty-five bobs,’ conceded Joolby. ‘Take me or leave it,’ and since there was nothing else to be done, this being in fact quite up to his meagre expectation, Chilly held out his hand and took it, only revenging himself by the impudent satisfaction of ostentatiously holding up the note to the light when it was safely in his possession.

‘You need not do that, my young fellow,’ remarked Mr Joolby, observing the action. ‘I know a dud note when I see it.’

‘Oh I don’t doubt that you know one all right, Mr Joolby,’ replied Fank with gutter insolence. ‘It’s this bloke I’m thinking of. You’ve had a lot more experience than me in that way, you see, so I’ve got to be blinkin’ careful,’ and as he turned to go a whole series of portentous nods underlined a mysterious suggestion.

‘What do you mean, you rascal?’ For the first time a possible note of misgiving tinged Mr Joolby’s bloated assurance. ‘Not that it matters—there’s nothing about me to talk of—but have you been—been hearing anything?’

It was Mr Fank’s turn to be cocky: if he couldn’t wangle that extra fifteen bob out of The Toad he could evidently give him the shivers.

‘Hearing, sir?’ he replied from the door, with an air of exaggerated guilelessness. ‘Oh no, Mr Joolby: whatever should I be hearing? Except that in the City you’re very well spoken of to be the next Lord Mayor!’ and to leave no doubt that this pleasantry should be fully understood he took care that his parting aside reached Joolby’s ear: ‘I don’t think!’

‘Fank. Chilly Fank,’ mused Mr Joolby as he returned to his private lair, carrying the newly acquired purchase with him and progressing even more grotesquely than his wont since he could only use one stick for assistance. ‘The last time he came he had an amusing remark to make, something about keeping an aquarium …’

Won Chou was still at his observation post when the door opened again an hour later. Again he sped his message—a different intimation from the last, but conveying a sign of doubt for this time the watcher could not immediately ‘place’ the visitors. These were two, both men—‘a belong number one and a belong number two chop men,’ sagely decided Won Chou—but there was something about the more important of the two that for the limited time at his disposal baffled the Chinaman’s deduction. It was not until they were in the shop and he was attending to them that Won Chou astutely suspected this man perchance to be blind—and sought for a positive indication. Yet he was the one who seemed to take the lead rather than wait to be led and except on an occasional trivial point his movements were entirely free from indecision. Certainly he had paused at the step but that was only the natural hesitation of a stranger to the parts and it was apparently the other who supplied the confirmation.

‘This is the right place by the description, sir,’ the second man said.

‘It is the right place by the smell,’ was the reply, as soon as the door was opened. ‘Twenty centuries and a hundred nationalities mingle here, Parkinson. And not the least foreign—’

‘A native of some description, sir,’ tolerantly supplied the literal Parkinson, taking this to apply to the attendant as he came forward.

‘Can do what?’ politely inquired Won Chou, bowing rather more profoundly than the average shopman would, even to a customer in whom he can recognise potential importance.

‘No can do,’ replied the chief visitor, readily accepting the medium. ‘Bring number one man come this side.’

‘How fashion you say what want?’ suggested Won Chou hopefully.

‘That belong one piece curio house man.’

‘He much plenty busy this now,’ persisted Won Chou, faithfully carrying out his instructions. ‘My makee show carpet, makee show cabinet, chiney, ivoly, picture—makee show one ting, two ting, any ting.’

‘Not do,’ was the decided reply. ‘Go make look-see one time.’

‘All same,’ protested Won Chou, though he began to obey the stronger determination, ‘can do heap wella. Not is?’

A good natured but decided shake of the head was the only answer, and looking extremely sad and slightly hurt Won Chou melted through the doorway—presumably to report beyond that: ‘Much heap number one man make plenty bother.’

‘Look round, Parkinson,’ said his master guardedly. ‘Do you see anything here in particular?’

‘No, sir; nothing that I should designate noteworthy. The characteristic of the emporium is an air of remarkable untidiness.’

‘Yet there is something unusual,’ insisted the other, lifting his sightless face to the four quarters of the shop in turn as though he would read their secret. ‘Something unaccountable, something wrong.’

‘I have always understood that the East End of London was not conspicuously law-abiding,’ assented Parkinson impartially. ‘There is nothing of a dangerous nature impending, I hope, sir?’

‘Not to us, Parkinson; not as yet. But all around there’s something—I can feel it—something evil.’

‘Yes, sir—these prices are that.’ It was impossible to suspect the correct Parkinson of ever intentionally ‘being funny’ but there were times when he came perilously near incurring the suspicion. ‘This small extremely second-hand carpet—five guineas.’

‘Everywhere among this junk of centuries there must be things that have played their part in a hundred bloody crimes—can they escape the stigma?’ soliloquised the blind man, beginning to wander about the bestrewn shop with a self-confidence that would have shaken Won Chou’s conclusions if he had been looking on—especially as Parkinson, knowing by long experience the exact function of his office, made no attempt to guide his master. ‘Here is a sword that may have shared in the tragedy of Glencoe, this horn lantern lured some helpless ship to destruction on the Cornish coast, the very cloak perhaps that disguised Wilkes Booth when he crept up to shoot Abraham Lincoln at the play.’

‘It’s very unpleasant to contemplate, sir,’ agreed Parkinson discreetly.

‘But there is something more than that. There’s an influence—a force—permeating here that’s colder and deeper and deadlier than revenge or greed or decent commonplace hatred … It’s inhuman—unnatural—diabolical. And it’s coming nearer, it begins to fill the air—’ He broke off almost with a physical shudder and in the silence there came from the passage beyond the irregular thuds of Joolby’s sticks approaching. ‘It’s poison,’ he muttered; ‘venom.’

‘Had we better go before anyone comes, sir?’ suggested Parkinson, decorously alarmed. ‘As yet the shop is empty.’

‘No!’ was the reply, as though forced out with an effort. ‘No—face it!’ He turned as he spoke towards the opening door and on the word the uncouth figure, laboriously negotiating the awkward corners, entered. ‘Ah, at last!’

‘Well, you see, sir,’ explained Mr Joolby, now the respectful if somewhat unconventional shopman in the presence of a likely customer, ‘I move slowly so you must excuse being kept waiting. And my boy here—well-meaning fellow but so economical even of words that each one has to do for half a dozen different things—quite different things sometimes.’

‘Man come. Say “Can do”; say “No can do”. All same; go tell; come see,’ protested Won Chou, retiring to some obscure but doubtless ingeniously arranged point of observation, and evidently cherishing a slight sense of unappreciation.

‘Exactly. Perfectly explicit.’ Mr Joolby included his visitors in his crooked grin of indulgent amusement. ‘Now those poisoned weapons you wrote about. I’ve looked them up and I have a wonderful collection and, what is very unusual, all in their original condition. This,’ continued Mr Joolby, busying himself vigorously among a pile of arrows with padded barbs, ‘is a very fine example from Guiana—it guarantees death with convulsions and foaming at the mouth within thirty seconds. They’re getting very rare now because since the natives have become civilized by the missionaries they’ve given up their old simple ways of life—they will have our second-hand rifles because they kill much further.’

‘Highly interesting,’ agreed the customer, ‘but in my case—’

‘Or this beautiful little thing from the Upper Congo. It doesn’t kill outright, but, the slightest scratch—just the merest pin prick—and you turn a bright pea green and gradually swell larger and larger until you finally blow up in a very shocking manner. The slightest scratch—so,’ and in his enthusiasm Mr Joolby slid the arrow quickly through his hand towards Parkinson whose face had only too plainly reflected a fascinated horror from the moment of their host’s appearance. ‘Then the tapioca-poison group from Bolivia—’

‘Save yourself the trouble,’ interrupted the blind man, who had correctly interpreted his attendant’s startled movement. ‘I’m not concerned with—the primitive forms of murder.’

‘Not—?’ Joolby pulled up short on the brink of another panegyric, ‘not with poisoned arrows? But aren’t you the Mr Brooks who was to call this afternoon to see what I had in the way of—?’

‘Some mistake evidently. My name is Carrados and I have made no appointment. Antique coins are my hobby—Greek in particular. I was told that you might probably have something in that way.’

‘Coins; Greek coins.’ Mr Joolby was still a little put out by the mischance of his hasty assumption. ‘I might have; I might have. But coins of that class are rather expensive.’

‘So much the better.’

‘Eh?’ Customers in Padgett Street did not generally, one might infer, express approval on the score of dearness.

‘The more expensive they are, the finer and rarer they will be—naturally. I can generally be satisfied with the best of anything.’

‘So—so?’ vaguely assented the dealer, opening drawer after drawer in the various desks and cabinets around and rooting about with elaborate slowness. ‘And you know all about Greek coins then?’

‘I hope not,’ was the smiling admission.

‘Hope not? Eh? Why?’

‘Because there would be nothing more to learn then. I should have to stop collecting. But doubtless you do?’

‘If I said I did—well, my mother was a Greek so that it should come natural. And my father was a—um, no; there was always a doubt about that man. But one grandfather was a Levantine Jew and the other an Italian cardinal. And one grandmamma was an American negress and the other a Polish revolutionary.’

‘That should ensure a tolerably versatile stock, Mr Joolby.’

‘And further back there was an authentic satyr came into the family tree—so I’m told,’ continued Mr Joolby, addressing himself to his prospective customer but turning to favour the scandalised Parkinson with an implicatory leer. ‘You find that amusing, Mr Carrados, I’m sure?’

‘Not half so amusing as the satyr found it I expect,’ was the retort. ‘But come now—’ for Mr Joolby had meanwhile discovered what he had sought and was looking over the contents of a box with provoking deliberation.

‘To be sure—you came for Greek coins, not for Greek family history, eh? Well, here is something very special indeed—a tetradrachm struck at Amphipolis, in Macedonia, by some Greek ruler of the province but I can’t say who. Perhaps Mr Carrados can enlighten me?’

Without committing himself to this the blind man received the coin on his outstretched hand and with subtile fingers delicately touched off the bold relief that still retained its superlative grace of detail. Next he weighed it carefully in a cupped palm, and then after breathing several times on the metal placed it against his lips. Meanwhile Parkinson looked on with the respect that he would have accorded to any high-class entertainment; Joolby merely sceptically indifferent.

‘Yes,’ announced Carrados at the end of this performance, ‘I think I can do that. At all events I know the man who made it.’

‘Come, come, use your eyes, my good sir,’ scoffed Mr Joolby with a contemptuous chuckle. ‘I thought you understood at least something about coins. This isn’t—I don’t know what you think—a Sunday school medal or a stores ticket. It’s a very rare and valuable specimen and it’s at least two thousand years old. And you “know the man who made it”!’

‘I can’t use my eyes because my eyes are useless: I am blind,’ replied Carrados with unruffled evenness of temper. ‘But I can use my hands, my finger-tips, my tongue, lips, my commonplace nose, and they don’t lead me astray as your credulous, self-opinionated eyes seem to have done—if you really take this thing for a genuine antique,’ and with uncanny proficiency he tossed the coin back into the box before him.

‘You can’t see—you say that you are blind—and yet you tell me, an expert, that it’s a forgery!’

‘It certainly is a forgery, but an exceptionally good one at that—so good that no one but Pietro Stelli, who lives in Padua, could in these degenerate days have made it. Pietro makes such beautiful forgeries that in my less experienced years they have taken even me in. Of course I couldn’t have that so I went to Padua to find out how he worked, and Peter, who is, according to his lights, as simple and honest a soul as ever breathed, willingly let me watch him at it.’

‘And how,’ demanded Mr Joolby, seeming almost to puff out aggression towards this imperturbable braggart; ‘how could you see him what you call “at it”, if, as you say, you are blind? You are just a little too clever, Mr Carrados.’

‘How could I see? Exactly as I can see’—stretching out his hand and manipulating the extraordinarily perceptive fingers meaningly—‘any of the ingenious fakes which sharp people offer the blind man; exactly as I could see any of the thousand and one things that you have about your shop. This’—handling it as he seemed to look tranquilly at Mr Joolby—‘this imitation Persian prayer-rug with its lattice-work design and pomegranate scroll, for instance; exactly as I could, if it were necessary, see you,’ and he took a step forward as though to carry out the word, if Mr Joolby hadn’t hastily fallen back at the prospect.

The prayer-rug was no news to Mr Joolby—although it was ticketed five guineas—but he had had complete faith in the tetradrachm notwithstanding that he had bought it at the price of silver; and despite the fact that he would still continue to describe it as a matchless gem it was annoying to have it so unequivocally doubted. He picked up the box without offering any more of its contents, and hobbling back to the desk with it slammed the drawer home in swelling mortification.

‘Well, if that is your way of judging a valuable antique, Mr Carrados, I don’t think that we shall do any business. I have nothing more to show, thank you.’

‘It is my way of judging everything—men included—Mr Joolby, and it never, never fails,’ replied Carrados, not in the least put out by the dealer’s brusqueness. It was a frequent grievance with certain of this rich and influential man’s friends that he never appeared to resent a rudeness. ‘And why should I,’ the blind man would cheerfully reply, ‘when I have the excellent excuse that I do not see it?’

‘Of course I don’t mean by touch alone,’ he continued, apparently unconscious of the fact that Mr Joolby’s indignant back was now pointedly towards him. ‘Taste, when it’s properly treated, becomes strangely communicative; smell’—there could be no doubt of the significance of this allusion from the direction of the speaker’s nose—‘the chief trouble is that at times smell becomes too communicative. And hearing—I daren’t even tell you what a super-trained ear sometimes learns of the goings-on behind the scenes—but a blind man seldom misses a whisper and he never forgets a voice.’

Apparently Mr Joolby was not interested in the subtleties of perception for he still remained markedly aloof, and yet, had he but known it, an exacting test of the boast so confidently made was even then in process, and one moreover surprisingly mixed up with his own plans. For at that moment, as the visitor turned to go, the inner door was opened a cautious couple of inches and:

‘Look here, J.J.,’ said the unseen in a certainly distinctive voice, ‘I hope you know that I’m waiting to go. If you’re likely to be another week—’

‘Don’t neglect your friend on our account, Mr Joolby,’ remarked Carrados very pleasantly—for Won Chou had at once slipped to the unlatched door as if to head off the intruder. ‘I quite agree. I don’t think that we are likely to do any business either. Good day.’

‘Dog dung!’ softly spat out Mr Joolby as the shop door closed on their departing footsteps.

CHAPTER III

MR BRONSKY HAS MISGIVINGS

AS Mr Carrados and Parkinson left the shop they startled a little group of street children who after the habit of their kind were whispering together, giggling, pushing one another about, screaming mysterious taunts, comparing sores and amusing themselves in the unaccountable but perfectly satisfactory manner of street childhood. Reassured by the harmless appearance of the two intruders the impulse of panic at once passed and a couple of the most precocious little girls went even so far as to smile up at the strangers. More remarkable still, although Parkinson felt constrained by his imperviable dignity to look away, Mr Carrados unerringly returned the innocent greeting.

This incident entailed a break in which the appearance of the visitors, their position in life, place of residence, object in coming and the probable amount of money possessed by each were frankly canvassed, but when that source of entertainment failed the band fell back on what had been their stock game at the moment of interruption. This apparently consisted in daring one another to do various things and in backing out of the contest when the challenge was reciprocated. At last, however, one small maiden, spurred to desperation by repeated ‘dares’, after imploring the others to watch her do it, crept up the step of Mr Joolby’s shop, cautiously pushed open the door and standing well inside (the essence of the test as laid down), chanted in the peculiarly irritating sing-song of her tribe:

‘Toady, toady Jewlicks;

Crawls about on two sticks.

Toady, toady—’

‘Makee go away,’ called out Won Chou from his post, and this not being at once effective he advanced towards the door with a mildly threatening gesture. ‘Makee go much quickly, littee cow-child. Shall do if not gone is.’

The young imp had been prepared for immediate flight the instant anyone appeared, but for some reason Won Chou’s not very aggressive behest must have conveyed a peculiarly galling insult for its effect was to transform the wary gamin into a bristling little spitfire, who hurled back the accumulated scandal of the quarter.