Полная версия

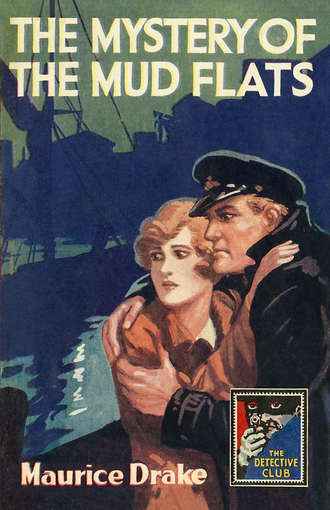

The Mystery of the Mud Flats

‘Off with you,’ he said cheerily. ‘On hatches and clear out and make room for your betters.’

‘The Olive Leaf again?’ I asked.

‘The Kismet. She passed the Hasborough last night with a fair wind. Guess she’s outside the river now, waiting tide.’

‘What’s she bringing?’ I asked.

‘What business is that of yours?’ He put on his standoffish manner in an instant. ‘You’re not paid to ask questions, but to obey orders. Just remember your place, Capt’n, and I’ll remember mine.’

I raged inwardly for having laid myself open to the snub. The brute had been genial as a blood-relation till then. But it was no good quarrelling with one’s livelihood, so we got away without another word. Voogdt took the wheel when we got into the main stream.

‘What’s the Hasborough?’ he asked.

‘A lightship off Norfolk.’

‘Then if the Kismet passed her yesterday, she’s been north, that’s obvious. And if she’s been north, it’s a hundred to one she’s carrying coal. And if she’s carrying coal, which is saleable anywhere, she’ll be loaded deep.’

‘Sherlock Holmes,’ I said, and went below.

When I came on deck half-an-hour later we were passing Flushing, and out at sea a small coaster about our own size was lying at anchor. She was comparatively light, riding high in the water.

‘There’s the Kismet, Sherlock,’ I jeered. ‘And if she’s got more than thirty tons aboard, I’m a Dutchman.’

‘Then either ’tisn’t the Kismet or she isn’t carrying coal,’ he said quietly. Half-an-hour later I had the laugh of him again, for we passed near enough for a glass to show her name in dirty white letters under her bows.

‘What d’ye make of that?’ I handed him my glasses and took the wheel.

He had a long stare and then turned and looked at me queerly.

‘Kismet it is, right enough. Down helm a wee, skipper, and get a bit closer.’

‘What for?’ I said; but I did as he asked.

‘Now hail ’em,’ he said, when we’d got close enough. He was itching with excitement and curiosity.

‘Ahoy!’ I shouted. ‘Kismet, ahoy!’

‘Ahoy!’ came down the wind.

‘Ask ’em where they’re bound,’ Voogdt prompted.

‘Where—are—you—bound?’

‘Goole to Terneuzen with coals,’ came the answer.

‘There you are,’ I said. ‘Now you know. Like most of you private detectives, you’re half right and half wrong. She is the Kismet, and you said she wasn’t. She’s come from the north and she’s got coals, just as you said. And she’s got half a cargo and not a full one, which is flat contrary to your notions. Now what d’ye make of it?’

‘I make rank unbusinesslike ways of it,’ he replied. ‘And on the face of it, that’s all one can say. I’m beat I admit.’

‘Well, what odds?’ I said. ‘We’ve got our money, and that’s enough. If the thing’s being mucked I’m sorry for Ward, but he’s big enough to manage his own affairs. I’ll mind mine, you mind yours, and everybody’ll be pleased.

‘Poking my nose into things has been my business for some years,’ Voogdt snapped at me. ‘You can’t drop the habits of a lifetime in ten minutes, you dunderhead,’ and after that stuck to his wheel, grumbling about dolts and thickwits under his breath.

We were bound for Poole this time, and no sooner had we got our ballast on the quay than Ward made his appearance. Voogdt stared at him hard, and late in the evening came aboard full of information about him.

‘He’s a chemist. He’s got a professor’s job at Mason College, Birmingham.’

‘He’s a sound man—a worker. He’s had the gold medal of the Royal Society of Arts, is a Felton prizeman and heaps more besides. What on earth can he be doing dabbling in a little trading concern like this? A man with his record could get to the top, if he liked, and yet here he is tinkering at this business with a cub like Willis Cheyne for a manager. He isn’t a fool, yet he behaves like one.’

‘Oh, hang!’ I said. ‘You worry me with your twaddle. Let’s do our work, and draw our pay and live in peace. Go to bed. We start loading potatoes tomorrow at six a.m.’

‘Potatoes!’ he said wearily. ‘They’re shipping potatoes to an agricultural country now. Next time we shall carry windmills in sections, or canal water. They’re short of both in Holland, and naturally can pay big freights on ’em. Good-night, 0 massive-brained ruminant. Good-night.’

I thought potatoes were a funny cargo myself, but I wouldn’t encourage him in his silly ways and so swore I considered it natural they should be imported. ‘There’s Ghent handy,’ I said, as we were squabbling about it on the way up Channel. ‘Ghent and all the other Belgian industrial centres close by. A big population wants food, don’t it?—and industries want deals and clay and coal.’

‘In half cargoes!’ he jerked out; but I had him there, having been thinking about the Kismet myself.

‘That’s because of the tide,’ I said. ‘How could they get deep-laden boats, even of our light draught over those mud-banks at neap tides?’

That shut him up and so ended the discussion for the time being and we got in, discharged our potatoes and ballasted as before. Some of the Kismet’s coal still lay by the warehouse, but not more than ten tons at the outside. The rest was gone. Even Voogdt grudgingly admitted there was nothing unusual to comment upon.

But the evening before we sailed we had a shock. Our bags of potatoes were lying neatly stacked by the wharf, twenty-five tons of ballast were aboard, and the hatches were on, ready for sailing. Having an hour or two to wait for the tide I suggested to Voogdt that we should stroll along the bank to Terneuzen and have a drink before we went. When we got to the canal entrance we had to wait, the lock-gates being open. Right beside us was a German coasting schooner, and I thought I’d air my German a bit and impress Voogdt.

‘Wo gehen sie?’ I said to a boy on deck.

‘Emden. Mit Erdapfeln.’

He used the slang word ‘Erdapfeln’ instead of the more correct ‘Kartoffeln’ and I turned to Voogdt to translate without thinking of the sense of the words. But he needed no translator, it was evident.

‘Potatoes,’ he said under his breath, like one dazed. ‘Potatoes! Hear that?’ He leaned over and spoke to the boy himself.

‘Woher sint sie gekommen?’

‘Sas van Gent.’

The thing had soaked into my thick head by this time and we stared at each other in silent amazement. I was being paid a sovereign a ton to bring potatoes three hundred miles to Terneuzen; whilst Sas van Gent, only ten miles up the canal, was exporting them in bulk to Emden. No explanations could spare that. We forgot the drink we’d come out for, and turned to walk back to the Luck and Charity with our heads in a whirl.

Half-way back I stopped in my stride. ‘I read a yarn once,’ I said, ‘about a man who saw a Government announcement in the papers that the Woods and Forests had oak-trees to sell, and another from the Admiralty to say that they wanted oak timber. So he stepped in and sold England her own property and retired on it.’

Voogdt patted me on the shoulder softly, speaking with exaggerated gentleness, as though to a sick child.

‘Don’t fash yourself, my son,’ he said. ‘This thing is beyond your great brain. ’Tisn’t a fool Government this time. It’s the rules of trade, and demand and supply, and a dozen other things, all being turned upside-down. It’s water flowing up a hill, James, that’s what it is. It’s rank raving lunacy, apparently run at a profit, and that’s impossible. Impossible, I tell you.’

Walking slowly and thinking hard, Cheyne overtook us as we neared the wharf, and asked us into the office for a drink. To my surprise Voogdt, answering him, put on a raw Cockney drawl, and spoke as though he were an illiterate coasting hand.

We sailed for Torquay this time, but conversation languished on the voyage. The more I thought of that German-bound boat the crazier the whole thing seemed, and, think as I would, I couldn’t see a light anywhere, Once or twice I made some sort of suggestion, more in protest against the clashing facts than anything else, but each time Voogdt shut me up sharp.

‘Oh! go and boil your head,’ he said rudely. ‘I’ve been over and under and all round it; and all I can say is that it’s against nature. But you mark my words, Mr James Carthew Hyphen West, if any more funny things like that happen, I shall go slap off my rocker.’

Another cargo of potatoes awaited us at Torquay, and Voogdt nearly danced on the deck when I told him so.

‘I hate being beat. That’s what I’m suffering from,’ he said, half laughing at himself. ‘After all, the explanation’s clear enough. Ward or somebody in the company has money, and Cheyne’s induced ’em to put it in this fool venture. When it’s gone the company will shut shop and Cheyne’ll go to sea again, having had a royal holiday ashore. That’s all. It can’t be anything else Let’s get the spuds aboard I hate doing it I hate waste. But after all we may as well have some unknown fool’s money as anybody else. Here’s my last word about it, skipper; always see you’re paid in advance and lay by against a rainy day.’

There was no difficulty about that. Cheyne was always ready to make an advance whenever I asked him, even when sometimes the money was for my own purposes. We sprung our topmast a month later, and though, strictly speaking, I ought to have paid for repairs myself, Cheyne authorised me to get a new spar at his expense. ‘Get a good stick and don’t waste time about it.’ That was always his cry. ‘Hurry. Hurry. Make quick voyages.’

‘And he’s losing money on every voyage, sure,’ Voogdt said once almost despairingly.

After the second potato trip he wrote to a friend of his in London, asking for particulars of our employers, only to find the so-called company was not registered as a company at all. He showed me the letter.

‘There you are,’ said he. ‘That settles it. They must have got hold of a capitalist mug, and they’re bleeding him. Only—’ He stopped.

‘Only what?’

‘Well, I should have thought a fellow like Cheyne would have opened his sham store in a more amusing place. The Riviera, say. And there’s Ward. Cheyne may be a rogue and a fool, but Ward’s neither, if I’m any judge of a man. What’s he doing in that galley?’

It didn’t worry me that I couldn’t answer his questions—if I can’t understand a thing, I just disregard it and get on with the work; but to him unsatisfied curiosity was like a prickle in his flesh.

However, as time wore on he seemed to be easier in his mind, and after a few trips we’d got the hang of the trade and were just making voyage after voyage without remark. Each voyage was much like the last. We nearly always had light cargoes, and took away as much ballast as we could get in two tides. We always traded in the English Channel, and nearly always to different ports. In fact the only port we called at twice was Dartmouth, and on our second visit, three months after the first, we lay at Kingswear, on the other side of the river. In those three months we’d made about ten journeys: to Looe, Penzance, Falmouth, Fowey, Teignmouth, Plymouth, Newhaven, Southampton and Kingsbridge. By that time we were so accustomed to the round that even Voogdt accepted each new order without remark.

My bank account was growing and as I’d given Voogdt and ’Kiah bonuses from time to time, we were a flourishing concern. Whatever folly the company represented we had no reason to complain.

Early in September we were ordered to Guernsey, but just outside the Scheldt it came on to blow real nasty from the south-west. It looked like an equinoctial gale, and we stood across to the North Foreland intending to drop anchor there till it blew itself out. It lasted two days, and whilst we were lying at anchor we saw the Kismet coming down river towards us, reefed down but with a bit of topsail hoisted. Just as she passed Birchington, about a mile from us, she got a sudden buster of a squall off the shore, and before you could say ‘knife’ her topmast was over her side. She luffed up towards the shore, all she could, and dropped anchor to clear away the raffle and mess. At Voogdt’s suggestion we rowed over in our dinghy to proffer assistance. The wind was gusty and strong, but the water smooth, and we soon reached her and climbed aboard.

The skipper, elderly, and a typical coasting master, stood in the waist placidly directing his three hands as they hacked and cut away the wreckage. He was dressed coaster-fashion, in blue coat, guernsey and trousers, gaudy red carpet slippers and a bowler hat, once black, but now green with age. He nodded to us as we went to bear a hand, and when things were getting tidy invited us into his cabin and offered us a drink.

I told him we were from the Luck and Charity, and that turned our talk on our only mutual acquaintances—our employers. The old man seemed well pleased with them, and apparently knew a good deal more about them than we did.

‘Mr Cheyne—a fine young fellow ’e is. A true sailor, I call i’m. Miss Brand’s ’is cousin—she’s a most amoosin’ young person; and there’s Miss Lavington. She’s a real lady, that.’

‘Have Miss Brand and Miss Lavington got anything to do with the company, then?’ I asked in surprise.

‘Sure-ly. It’s mostly Miss Lavington’s money in it. Mr Ward, ’e’s a partner, too. Them four.’

I caught Voogdt’s eye. ‘Only those four?’ I asked.

‘I don’t know of any other.’

‘Have you been with them long?’

‘Jus’ over a year. I signed charter for another year only las’ month. Good people, they are. Mr Ward spoke mos’ complimentary about the last year’s working, an’ gave me a fifty-pound bonus an’ a shilling a ton rise.’

‘What are you getting now, then, Capt’n?’

‘Nine-an-six a ton burthen between the Tyne an’ Terneuzen.’

‘Don’t you go farther north than the Tyne?’

‘No. The Olive Leaf, she trades from the Scotch ports. They’re thinking of putting on another boat for the Irish Sea. If they can’t get one to suit them, Mr Ward says they’ll build.’

Voogdt asked a question, forgetting that etiquette demanded he should hold his tongue in the presence of his betters, and the old skipper shut him up at once. After that we both felt rather uncomfortable and took our leave as early as we could.

Next day the wind eased a bit and shifted into the north-west, so we set sail for Guernsey. The last we saw of the Kismet as we rounded the Foreland her people were getting their new topmast aloft.

CHAPTER V

IN THE MATTER OF A DESERTING SEAMAN

AS a general rule one of the most talkative of men, Voogdt none the less had his silent days, days when he grudged even monosyllables, only grunting assent or dissent in answer to direct questions. Sometimes such a mood would last him half-a-week; once it was over he talked like a mill, as though to make up for lost time. He was a good talker, and his silences were the less agreeable for the contrast.

Throughout the summer I had never known him so silent as during this trip to Guernsey. The gale had left a long sea behind it that did nothing to enhance our comfort aboard, and a sulky shipmate only added to my annoyance. By the time we reached St Peters Port I could have kicked him with the greatest goodwill in the world.

He cheered up a bit when we got in harbour, and I began to be sorry for him—with a little touch of contempt, perhaps—thinking that it was the roughish weather he had been suffering from. He worked well, as he always did now, getting out the ballast, but in the evening staggered me by announcing that he was leaving the Luck and Charity.

‘What on earth for?’ I asked, fairly taken aback.

‘That was our agreement, James, if you remember. I was to leave you where and when I pleased. Well, I please now and here.’

‘But why? Have I done anything?’

‘What haven’t you done? You picked me up out at elbows and starving, and you’ve put fresh life into me. That’s what you’ve done. And I’m going to repay you by deserting just as the winter’s coming on. I feel a sweep, old man, but I must go.’

‘Is it the winter you’re afraid of?’ I asked.

‘Call it that. I can’t give you a better reason or I would. Don’t make any more difficulties about it. I feel ashamed to leave you like this, but I tell you I must go. That’s all.’

‘What are you going to do? Have you enough money to get on with?’

‘No; I haven’t. That’s another thing I had qualms in tackling you about. Will you lend me forty or fifty quid? I can’t give you any security beyond my bare promise to repay.’

That was a surprise. Of course his pay hadn’t been large—only thirty bob a week—but, as I was doing well, I had considered it my place to make things easier for the other two. On weekly boats the men are expected to find themselves out of their weekly thirty shillings, but Voogdt had messed with me, and both he and ’Kiah had drawn good bonuses on each voyage. ’Kiah I knew had banked nearly twenty pounds, and I told Voogdt so.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.