Полная версия

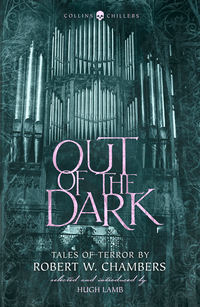

Out of the Dark: Tales of Terror by Robert W. Chambers

‘No,’ said Barris, hastily swallowing his coffee, ‘it’s of no importance; you can tell me about the beast—’

‘Serve you right if I had it brought in on toast,’ I returned.

Pierpont came in radiant, fresh from the bath.

‘Go on with your story, Roy,’ he said; and I told them about Godfrey and his reptile pet.

‘Now what in the name of common sense can Godfrey find interesting in that creature?’ I ended, tossing my cigarette into the fireplace.

‘It’s Japanese, don’t you think?’ said Pierpont.

‘No,’ said Barris, ‘it is not artistically grotesque, it’s vulgar and horrible – it looks cheap and unfinished—’

‘Unfinished – exactly,’ said I, ‘like an American humorist—’

‘Yes,’ said Pierpont, ‘cheap. What about that gold serpent?’

‘Oh, the Metropolitan Museum bought it; you must see it, it’s marvelous.’

Barris and Pierpont had lighted their cigarettes and, after a moment, we all rose and strolled out to the lawn, where chairs and hammocks were placed under the maple trees.

David passed, gun under arm, dogs heeling.

‘Three guns on the meadows at four this afternoon,’ said Pierpont.

‘Roy,’ said Barris as David bowed and started on, ‘what did you do yesterday?’

This was the question that I had been expecting. All night long I had dreamed of Ysonde and the glade in the woods, where, at the bottom of the crystal fountain, I saw the reflection of her eyes. All the morning while bathing and dressing I had been persuading myself that the dream was not worth recounting and that a search for the glade and the imaginary stone carving would be ridiculous. But now, as Barris asked the question, I suddenly decided to tell him the whole story.

‘See here, you fellows,’ I said abruptly, ‘I am going to tell you something queer. You can laugh as much as you please to, but first I want to ask Barris a question or two. You have been in China, Barris?’

‘Yes,’ said Barris, looking straight into my eyes.

‘Would a Chinaman be likely to turn lumberman?’

‘Have you seen a Chinaman?’ he asked in a quiet voice.

‘I don’t know; David and I both imagined we did.’

Barris and Pierpont exchanged glances.

‘Have you seen one also?’ I demanded, turning to include Pierpont.

‘No,’ said Barris slowly; ‘but I know that there is, or has been, a Chinaman in these woods.’

‘The devil!’ said I.

‘Yes,’ said Barris gravely; ‘the devil, if you like – a devil – a member of the Kuen-Yuin.’

I drew my chair close to the hammock where Pierpont lay at full length, holding out to me a ball of pure gold.

‘Well?’ said I, examining the engraving on its surface, which represented a mass of twisted creatures – dragons, I supposed.

‘Well,’ repeated Barris, extending his hand to take the golden ball, ‘this globe of gold engraved with reptiles and Chinese hieroglyphics is the symbol of the Kuen-Yuin.’

‘Where did you get it?’ I asked, feeling that something startling was impending.

‘Pierpont found it by the lake at sunrise this morning. It is the symbol of the Kuen-Yuin,’ he repeated, ‘the terrible Kuen-Yuin, the sorcerers of China, and the most murderously diabolical sect on earth.’

We puffed our cigarettes in silence until Barris rose, and began to pace backward and forward among the trees, twisting his gray moustache.

‘The Kuen-Yuin are sorcerers,’ he said, pausing before the hammock where Pierpont lay watching him; ‘I mean exactly what I say – sorcerers. I’ve seen them – I’ve seen them at their devilish business, and I repeat to you solemnly, that as there are angels above, there is a race of devils on earth and they are sorcerers. Bah!’ he cried, ‘talk to me of Indian magic and Yogis and all that clap-trap! Why, Roy, I tell you that the Kuen-Yuin have absolute control of a hundred millions of people, mind and body, body and soul. Do you know what goes on in the interior of China? Does Europe know – could any human being conceive of the condition of that gigantic hellpit? You read the papers, you hear diplomatic twaddle about Li Hung Chang and the Emperor, you see accounts of battles on sea and land, and you know that Japan has raised a toy tempest along the jagged edge of the great unknown. But you never before heard of the Kuen-Yuin; no, nor has any European except a stray missionary or two, and yet I tell you that when the fires from this pit of hell have eaten through the continent to the coast, the explosion will inundate half a world – and God help the other half.’

Pierpont’s cigarette went out; he lighted another, and looked hard at Barris.

‘But,’ resumed Barris quietly, ‘“sufficient unto the day”, you know – I didn’t intend to say as much as I did – it would do no good – even you and Pierpont will forget it – it seems so impossible and so far away – like the burning out of the sun. What I want to discuss is the possibility or probability of a Chinaman – a member of the Kuen-Yuin, being here, at this moment, in the forest.’

‘If he is,’ said Pierpont, ‘possibly the gold-makers owe their discovery to him.’

‘I do not doubt it for a second,’ said Barris earnestly.

I took the little golden globe in my hand, and examined the characters engraved upon it.

‘Barris,’ said Pierpont, ‘I can’t believe in sorcery while I am wearing one of Sanford’s shooting suits in the pocket of which rests an uncut volume of the “Duchess”.’

‘Neither can I,’ I said, ‘for I read the Evening Post, and I know Mr Godkin would not allow it. Hello! What’s the matter with this gold ball?’

‘What is the matter?’ said Barris grimly.

‘Why – why – it’s changing color – purple, no, crimson – no, it’s green I mean – good Heavens! these dragons are twisting under my fingers—’

‘Impossible!’ muttered Pierpont, leaning over me; ‘those are not dragons—’

‘No!’ I cried excitedly; ‘they are pictures of that reptile that Barris brought back – see – see – how they crawl and turn—’

‘Drop it!’ commanded Barris; and I threw the ball on the turf. In an instant we had all knelt down on the grass beside it, but the globe was again golden, grotesquely wrought with dragons and strange signs.

Pierpont, a little red in the face, picked it up, and handed it to Barris. He placed it on a chair, and sat down beside me.

‘Whew!’ said I, wiping the perspiration from my face, ‘how did you play us that trick, Barris?’

‘Trick?’ said Barris contemptuously.

I looked at Pierpont, and my heart sank. If this was not a trick, what was it? Pierpont returned my glance and colored, but all he said was, ‘It’s devilish queer,’ and Barris answered, ‘Yes, devilish’. Then Barris asked me again to tell my story, and I did, beginning from the time I met David in the spinney to the moment when I sprang into the darkening thicket where that yellow mask had grinned like a phantom skull.

‘Shall we try to find the fountain?’ I asked after a pause.

‘Yes – and – er – the lady,’ suggested Pierpont vaguely.

‘Don’t be an ass,’ I said a little impatiently, ‘you need not come, you know.’

‘Oh, I’ll come,’ said Pierpont, ‘unless you think I am indiscreet—’

‘Shut up, Pierpont,’ said Barris, ‘this thing is serious; I never heard of such a glade or such a fountain, but it’s true that nobody knows this forest thoroughly. It’s worthwhile trying for; Roy, can you find your way back to it?’

‘Easily,’ I answered; ‘when shall we go?’

‘It will knock our snipe shooting on the head,’ said Pierpont, ‘but when one has the opportunity of finding a live dream-lady—’

I rose, deeply offended, but Pierpont was not very penitent and his laughter was irresistible.

‘The lady’s yours by right of discovery,’ he said, ‘I’ll promise not to infringe on your dreams – I’ll dream about other ladies—’

‘Come, come,’ said I, ‘I’ll have Howlett put you to bed in a minute. Barris, if you are ready – we can get back to dinner—’

Barris had risen and was gazing at me earnestly.

‘What’s the matter?’ I asked nervously, for I saw that his eyes were fixed on my forehead, and I thought of Ysonde and the white crescent scar.

‘Is that a birthmark?’ said Barris.

‘Yes – why, Barris?’

‘Nothing – an interesting coincidence—’

‘What! – for Heaven’s sake!’

‘The scar – or rather the birthmark. It is the print of the dragon’s claw – the crescent symbol of Yue-Laou—’

‘And who the devil is Yue-Laou?’ I said crossly.

‘Yue-Laou – the Moon Maker, Dzil-Nbu of the Kuen-Yuin – it’s Chinese Mythology, but it is believed that Yue-Laou has returned to rule the Kuen-Yuin—’

‘The conversation,’ interrupted Pierpont, ‘smacks of peacocks’ feathers and yellow-jackets. The chicken pox has left its card on Roy, and Barris is guying us. Come on, you fellows, and make your call on the dream-lady. Barris, I hear galloping; here come your men.’

Two mud-splashed riders clattered up to the porch and dismounted at a motion from Barris. I noticed that both of them carried repeating rifles and heavy Colt revolvers.

They followed Barris, deferentially, into the dining room, and presently we heard the tinkle of plates and bottles and the low hum of Barris’ musical voice.

Half an hour later they came out again, saluted Pierpont and me, and galloped away in the direction of the Canadian frontier. Ten minutes passed, and, as Barris did not appear, we rose and went into the house, to find him. He was sitting silently before the table, watching the small golden globe, now glowing with scarlet and orange fire, brilliant as a live coal. Howlett, mouth ajar, and eyes starting from the sockets, stood petrified behind him.

‘Are you coming,’ asked Pierpont, a little startled. Barris did not answer. The globe slowly turned to pale gold again – but the face that Barris raised to ours was white as a sheet. Then he stood up, and smiled with an effort which was painful to us all.

‘Give me a pencil and a bit of paper,’ he said.

Howlett brought it. Barris went to the window and wrote rapidly. He folded the paper, placed it in the top drawer of his desk, locked the drawer, handed me the key, and motioned us to precede him.

When we again stood under the maples, he turned to me with an impenetrable expression. ‘You will know when to use the key,’ he said; ‘Come, Pierpont, we must try to find Roy’s fountain.’

VI

At two o’clock that afternoon, at Barris’ suggestion, we gave up the search for the fountain in the glade and cut across the forest to the spinney where David and Howlett were waiting with our guns and the three dogs.

Pierpont guyed me unmercifully about the ‘dream-lady’ as he called her, and, but for the significant coincidence of Ysonde’s and Barris’ questions concerning the white scar on my forehead, I should long ago have been perfectly persuaded that I had dreamed the whole thing. As it was, I had no explanation to offer. We had not been able to find the glade although fifty times I came to landmarks which convinced me that we were just about to enter it. Barris was quiet, scarcely uttering a word to either of us during the entire search. I had never before seen him depressed in spirits. However, when we came in sight of the spinney where a cold bit of grouse and a bottle of Burgundy awaited each, Barris seemed to recover his habitual good humor.

‘Here’s to the dream-lady!’ said Pierpont, raising his glass and standing up.

I did not like it. Even if she was only a dream, it irritated me to hear Pierpont’s mocking voice. Perhaps Barris understood – I don’t know, but he bade Pierpont drink his wine without further noise, and that young man obeyed with a childlike confidence which almost made Barris smile.

‘What about the snipe, David,’ I asked; ‘the meadows should be in good condition.’

‘There is not a snipe on the meadows, sir,’ said David solemnly.

‘Impossible,’ exclaimed Barris, ‘they can’t have left.’

‘They have, sir,’ said David in a sepulchral voice which I hardly recognized.

We all three looked at the old man curiously, waiting for his explanation of this disappointing but sensational report.

David looked at Howlett and Howlett examined the sky.

‘I was going,’ began the old man, with his eyes fastened on Howlett, ‘I was going along by the spinney with the dogs when I heard a noise in the covert and I seen Howlett come walkin’ very fast toward me. In fact,’ continued David, ‘I may say he was runnin’. Was you runnin’, Howlett?’

Howlett said ‘Yes’, with a decorous cough.

‘I beg pardon,’ said David, ‘but I’d rather Howlett told the rest. He saw things which I did not.’

‘Go on, Howlett,’ commanded Pierpont, much interested.

Howlett coughed again behind his large red hand.

‘What David says is true sir,’ he began; ‘I h’observed the dogs at a distance ’ow they was a workin’ sir, and David stood a lightin’ of ’s pipe be’ind the spotted beech when I see a ’ead pop up in the covert ’oldin’ a stick like ’e was h’aimin’ at the dogs sir—’

‘A head holding a stick?’ said Pierpont severely.

‘The ’ead ’ad ’ands, sir,’ explained Howlett, ‘’ands that ’eld a painted stick – like that, sir. ’Owlett, thinks I to myself, this ’ere’s queer, so I jumps in an’ runs, but the beggar ’e seen me an’ w’en I comes alongside of David ’e was gone. “’Ello ’Owlett,” sez David, “what the ’ell” – I beg pardon, sir – “’ow did you come ’ere,” sez ’e very loud. “Run!” sez I, “the Chinaman is harryin’ the dawgs!” “For Gawd’s sake wot Chinaman?” sez David, h’aimin’ ’is gun at every bush. Then I thinks I see ’im an’ we run an’ run, the dawgs a boundin’ close to heel sir, but we don’t see no Chinaman.’

‘I’ll tell the rest,’ said David, as Howlett coughed and stepped in a modest corner behind the dogs.

‘Go on,’ said Barris in a strange voice.

‘Well sir, when Howlett and I stopped chasin’, we was on the cliff overlooking the south meadow. I noticed that there was hundreds of birds there, mostly yellowlegs and plover, and Howlett seen them too. Then before I could say a word to Howlett, something out in the lake gave a splash – a splash as if the whole cliff had fallen into the water. I was that scared that I jumped straight into the bush and Howlett he sat down quick, and all those snipe wheeled up – there was hundreds – all asquealin’ with fright, and the woodduck came bowlin’ over the meadows as if the old Nick was behind.’

David paused and glanced meditatively at the dogs.

‘Go on,’ said Barris in the same strained voice.

‘Nothing more sir. The snipe did not come back.’

‘But that splash in the lake?’

‘I don’t know what it was sir.’

‘A salmon? A salmon couldn’t have frightened the duck and the snipe that way?’

‘No – oh no, sir. If fifty salmon had jumped they couldn’t have made that splash. Couldn’t they, Howlett?’

‘No ’ow,’ said Howlett.

‘Roy,’ said Barris at length, ‘what David tells us settles the snipe shooting for today. I am going to take Pierpont up to the house. Howlett and David will follow with the dogs – I have something to say to them. If you care to come, come along; if not, go and shoot a brace of grouse for dinner and be back by eight if you want to see what Pierpont and I discovered last night.’

David whistled Gamin and Mioche to heel and followed Howlett and his hamper toward the house. I called Voyou to my side, picked up my gun and turned to Barris.

‘I will be back by eight,’ I said; ‘you are expecting to catch one of the gold-makers are you not?’

‘Yes,’ said Barris listlessly.

Pierpont began to speak about the Chinaman but Barris motioned him to follow, and, nodding to me, took the path that Howlett and David had followed toward the house. When they disappeared I tucked my gun under my arm and turned sharply into the forest, Voyou trotting close to my heels.

In spite of myself the continued apparition of the Chinaman made me nervous. If he troubled me again I had fully decided to get the drop on him and find out what he was doing in the Cardinal Woods. If he could give no satisfactory account of himself I would march him in to Barris as a gold-making suspect – I would march him in anyway, I thought, and rid the forest of his ugly face. I wondered what it was that David had heard in the lake. It must have been a big fish, a salmon, I thought; probably David’s and Howlett’s nerves were overwrought after their Celestial chase.

A whine from the dog broke the thread of my meditation and I raised my head. Then I stopped short in my tracks.

The lost glade lay straight before me.

Already the dog had bounded into it, across the velvet turf to the carved stone where a slim figure sat. I saw my dog lay his silky head lovingly against her silken kirtle; I saw her face bend above him, and I caught my breath and slowly entered the sunlit glade.

Half timidly she held out one white hand.

‘Now that you have come,’ she said, ‘I can show you more of my work. I told you that I could do other things besides these dragonflies and moths carved here in stone. Why do you stare at me so? Are you ill?’

‘Ysonde,’ I stammered.

‘Yes,’ she said, with a faint color under her eyes.

‘I – I never expected to see you again,’ I blurted out, ‘—you – I – I – thought I had dreamed—’

‘Dreamed, of me? Perhaps you did, is that strange?’

‘Strange? N—no – but – where did you go when – when we were leaning over the fountain together? I saw your face – your face reflected beside mine and then – then suddenly I saw the blue sky and only a star twinkling.’

‘It was because you fell asleep,’ she said, ‘was it not?’

‘I – asleep?’

‘You slept – I thought you were very tired and I went back—’

‘Back? – where?’

‘Back to my home where I carve my beautiful images; see, here is one I brought to show you today.’

I took the sculptured creature that she held toward me, a massive golden lizard with frail claw-spread wings of gold so thin that the sunlight burned through and fell on the ground in flaming gilded patches.

‘Good Heavens!’ I exclaimed, ‘this is astounding! Where did you learn to do such work? Ysonde, such a thing is beyond price!’

‘Oh, I hope so,’ she said earnestly, ‘I can’t bear to sell my work, but my step-father takes it and sends it away. This is the second thing I have done and yesterday he said I must give it to him. I suppose he is poor.’

‘I don’t see how he can be poor if he gives you gold to model in,’ I said, astonished.

‘Gold!’ she exclaimed, ‘gold! He has a room full of gold! He makes it.’

I sat down on the turf at her feet completely unnerved.

‘Why do you look at me so?’ she asked, a little troubled.

‘Where does your step-father live?’ I said at last.

‘Here.’

‘Here!’

‘In the woods near the lake. You could never find our house.’

‘A house!’

‘Of course. Did you think I lived in a tree? How silly. I live with my step-father in a beautiful house – a small house, but very beautiful. He makes his gold there but the men who carry it away never come to the house, for they don’t know where it is and if they did they could not get in. My step-father carries the gold in lumps to a canvas satchel. When the satchel is full he takes it out into the woods where the men live and I don’t know what they do with it. I wish he could sell the gold and become rich for then I could go back to Yian where all the gardens are sweet and the river flows under the thousand bridges.’

‘Where is this city?’ I asked faintly.

‘Yian? I don’t know. It is sweet with perfume and the sound of silver bells all day long. Yesterday I carried a blossom of dried lotus buds from Yian, in my breast, and all the woods were fragrant. Did you smell it?’

‘Yes.’

‘I wondered last night whether you did. How beautiful your dog is; I love him. Yesterday I thought most about your dog but last night—’

‘Last night,’ I repeated below my breath.

‘I thought of you. Why do you wear the dragon claw?’

I raised my hand impulsively to my forehead, covering the scar.

‘What do you know of the dragon claw?’ I muttered.

‘It is the symbol of Ye-Laou, and Ye-Laou rules the Kuen-Yuin, my step-father says. My step-father tells me everything that I know. We lived in Yian until I was sixteen years old. I am eighteen now; that is two years we have lived in the forest. Look! – see those scarlet birds! What are they? There are birds of the same color in Yian.’

‘Where is Yian, Ysonde?’ I asked with deadly calmness.

‘Yian? I don’t know.’

‘But you have lived there?’

‘Yes, a very long time.’

‘Is it across the ocean, Ysonde?’

‘It is across seven oceans and the great river which is longer than from the earth to the moon.’

‘Who told you that?’

‘Who? My step-father; he tells me everything.’

‘Will you tell me his name, Ysonde?’

‘I don’t know it, he is my step-father, that is all.’

‘And what is your name?’

‘You know it, Ysonde.’

‘Yes, but what other name?’

‘That is all, Ysonde. Have you two names? Why do you look at me so impatiently?’

‘Does your step-father make gold? Have you seen him make it?’

‘Oh yes. He made it also in Yian and I loved to watch the sparks at night whirling like golden bees. Yian is lovely – if it is all like our garden and the gardens around. I can see the thousand bridges from my garden and the white mountain beyond—’

‘And the people – tell me of the people, Ysonde!’ I urged gently.

‘The people of Yian? I could see them in swarms like ants – oh! many, many millions crossing and recrossing the thousand bridges.’

‘But how did they look? Did they dress as I do?’

‘I don’t know. They were very far away, moving specks on the thousand bridges. For sixteen years I saw them every day from my garden but I never went out of my garden into the streets of Yian, for my step-father forbade me.’

‘You never saw a living creature nearby in Yian?’ I asked in despair.

‘My birds, oh such tall, wise-looking birds, all over gray and rose color.’

She leaned over the gleaming water and drew her polished hand across the surface.

‘Why do you ask me these questions,’ she murmured; ‘are you displeased?’

‘Tell me about your step-father,’ I insisted. ‘Does he look as I do? Does he dress, does he speak as I do? Is he American?’

‘American? I don’t know. He does not dress as you do and he does not look as you do. He is old, very, very old. He speaks sometimes as you do, sometimes as they do in Yian. I speak also in both manners.’

‘Then speak as they do in Yian,’ I urged impatiently, ‘speak as – why, Ysonde! why are you crying? Have I hurt you? – I did not intend – I did not dream of your caring! There Ysonde, forgive me – see, I beg you on my knees here at your feet.’

I stopped, my eyes fastened on a small golden ball which hung from her waist by a golden chain. I saw it trembling against her thigh, I saw it change color, now crimson, now purple, now flaming scarlet. It was the symbol of the Kuen-Yuin.

She bent over me and laid her fingers gently on my arm.

‘Why do you ask me such things?’ she said, while the tears glistened on her lashes. ‘It hurts me here—’ she pressed her hand to her breast – ‘it pains – I don’t know why. Ah, now your eyes are hard and cold again; you are looking at the golden globe which hangs from my waist. Do you wish to know also what that is?’

‘Yes,’ I muttered, my eyes fixed on the infernal colored flames which subsided as I spoke, leaving the ball a pale gilt again.