Полная версия

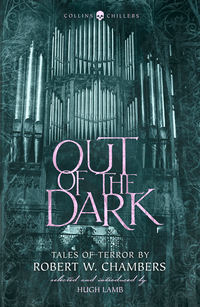

Out of the Dark: Tales of Terror by Robert W. Chambers

‘The callous brute!’ I muttered to myself, ‘I’ll wake him up – I’ll—’

I sat straight up on the bench and looked steadily at a figure which was moving toward me under the spluttering electric light.

It was the woman I had met in the Park.

She came straight up to me, her pale face gleaming like marble in the dark, her slim hands outstretched.

‘I have been looking for you all day – all day,’ she said, in the same low thrilling tones – ‘I want the letters back; have you them here?’

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘I have them here – take them in Heaven’s name; they have done enough evil for one day!’

She took the letters from my hand; I saw the ring, made of the double serpents, flashing on her slim finger, and I stepped closer, and looked her in the eyes.

‘Who are you?’ I asked.

‘I? My name is of no importance to you,’ she answered.

‘You are right,’ I said, ‘I do not care to know your name. That ring of yours—’

‘What of my ring?’ she murmured.

‘Nothing – a dead woman lying in the Morgue wears such a ring. Do you know what your letters have done? No? Well I read them to a miserable wretch and he blew his brains out!’

‘You read them to a man!’

‘I did. He killed himself.’

‘Who was that man?’

‘Captain d’Yniol—’

With something between a sob and a laugh she seized my hand and covered it with kisses, and I, astonished and angry, pulled my hand away from her cold lips and sat down on the bench.

‘You needn’t thank me,’ I said sharply; ‘if I had known that – but no matter. Perhaps after all the poor devil is better off somewhere in other regions with his sweetheart who was drowned – yes, I imagine he is. He was blind and ill – and broken-hearted.’

‘Blind?’ she asked gently.

‘Yes. Did you know him?’

‘I knew him.’

‘And his sweetheart, Aline?’

‘Aline,’ she repeated softly, ‘—she is dead. I come to thank you in her name.’

‘For what? – for his death?’

‘Ah, yes, for that.’

‘Where did you get those letters?’ I asked her, suddenly.

She did not answer, but stood fingering the wet letters.

Before I could speak again she moved away into the shadows of the trees, lightly, silently, and far down the dark walk I saw her diamond flashing.

Grimly brooding, I rose and passed through the Battery to the steps of the Elevated Road. These I climbed, bought my ticket, and stepped out to the damp platform. When a train came I crowded in with the rest, still pondering on my vengeance, feeling and believing that I was to scourge the conscience of the man who speculated on death.

At last the train stopped at 28th Street, and I hurried out and down the steps and away to the Morgue.

When I entered the Morgue, Skelton, the keeper, was standing before a slab that glistened faintly under the wretched gas jets. He heard my footsteps, and turned around to see who was coming. Then he nodded, saying, ‘Mr Hilton, just take a look at this here stiff – I’ll be back in a moment – this is the one that all the papers take to be Miss Tufft – but they’re all off, because this stiff has been here now for two weeks.’

I drew out my sketching-block and pencils.

‘Which is it, Skelton?’ I asked, fumbling for my rubber.

‘This one, Mr Hilton, the girl what’s smilin’. Picked up off Sandy Hook, too. Looks as if she was asleep, eh?’

‘What’s she got in her hand – clenched tight? Oh, a letter. Turn up the gas, Skelton, I want to see her face.’

The old man turned up the gas jet, and the flame blazed and whistled in the damp, fetid air. Then suddenly my eyes fell on the dead.

Rigid, scarcely breathing, I stared at the ring, made of two twisted serpents set with a great diamond – I saw the wet letters crushed in her slender hand – I looked, and – God help me! – I looked upon the dead face of the girl with whom I had been speaking on the Battery!

‘Dead for a month at least,’ said Skelton, calmly.

Then, as I felt my senses leaving me, I screamed out, and at the same instant somebody from behind seized my shoulder and shook me savagely – shook me until I opened my eyes again and gasped and coughed.

‘Now then, young feller!’ said a Park policeman bending over me, ‘if you go to sleep on a bench, somebody’ll lift your watch!’

I turned, rubbing my eyes desperately.

Then it was all a dream – and no shrinking girl had come to me with damp letters – I had not gone to the office – there was no such person as Miss Tufft – Jamison was not an unfeeling villain – no, indeed! – he treated us all much better than we deserved, and he was kind and generous too. And the ghastly suicide! Thank God that also was a myth – and the Morgue and the Battery at night where that pale-faced girl had – ugh!

I felt for my sketch-block, found it; turned the pages of all the animals that I had sketched, the hippopotami, the buffalo, the tigers – ah! where was that sketch in which I had made the woman in shabby black the principal figure, with the brooding vultures all around and the crowd in the sunshine—? It was gone.

I hunted everywhere, in every pocket. It was gone.

At last I rose and moved along the narrow asphalt path in the falling twilight.

And as I turned into the broader walk, I was aware of a group, a policeman holding a lantern, some gardeners, and a knot of loungers gathered about something – a dark mass on the ground.

‘Found ’em just so,’ one of the gardeners was saying, ‘better not touch ’em until the coroner comes.’

The policeman shifted his bull’s-eye a little; the rays fell on two faces, on two bodies, half supported against a park bench. On the finger of the girl glittered a splendid diamond, set between the fangs of two gold serpents. The man had shot himself; he clasped two wet letters in his hand. The girl’s clothing and hair were wringing wet, and her face was the face of a drowned person.

‘Well, sir,’ said the policeman, looking at me; ‘you seem to know these two people – by your looks—’

‘I never saw them before,’ I gasped, and walked on, trembling in every nerve.

For among the folds of her shabby black dress I had noticed the end of a paper – my sketch that I had missed!

PASSEUR

When he had finished his pipe he tapped the brier bowl against the chimney until the ashes powdered the charred log smouldering across the andirons. Then he sat back in his chair, absently touched the hot pipe-bowl with the tip of each finger until it grew cool enough to be dropped into his coat pocket.

Twice he raised his eyes to the little American clock ticking upon the mantel. He had half an hour to wait.

The three candles that lighted the room might be trimmed to advantage; this would give him something to do. A pair of scissors lay open upon the bureau, and he rose and picked them up. For a while he stood dreamily shutting and opening the scissors, his eyes roaming about the room. There was an easel in the corner, and a pile of dusty canvases behind it; behind the canvases there was a shadow – that gray, menacing shadow that never moved.

When he had trimmed each candle he wiped the smoky scissors on a paint rag and flung them on the bureau again. The clock pointed to ten; he had been occupied exactly three minutes.

The bureau was littered with neckties, pipes, combs and brushes, matches, reels and fly-books, collars, shirt studs, a new pair of Scotch shooting stockings, and a woman’s work-basket.

He picked out all the neckties, folded them once, and hung them over a bit of twine that stretched across the looking-glass; the shirt studs he shovelled into the top drawer along with brushes, combs, and stockings; the reels and fly-books he dusted with his handkerchief and placed methodically along the mantelshelf. Twice he stretched out his hand towards the woman’s work-basket, but his hand fell to his side again, and he turned away into the room staring at the dying fire.

Outside the snow-sealed window a shutter broke loose and banged monotonously, until he flung open the panes and fastened it. The soft, wet snow, that had choked the window-panes all day, was frozen hard now, and he had to break the polished crust before he could find the rusty shutter hinge.

He leaned out for a moment, his numbed hands resting on the snow, the roar of a rising snow-squall in his ears; and out across the desolate garden and stark hedgerow he saw the flat black river spreading through the gloom.

A candle sputtered and snapped behind him; a sheet of drawing paper fluttered across the floor, and he closed the panes and turned back into the room, both hands in his worn pockets.

The little American clock on the mantel ticked and ticked, but the hands lagged, for he had not been occupied five minutes in all. He went up to the mantel and watched the hands of the clock. A minute – longer than a year to him – crept by.

Around the room the furniture stood ranged – a chair or two of yellow pine, a table, the easel, and in one corner the broad curtained bed; and behind each lay shadows, menacing shadows that never moved.

A little pale flame started up from the smoking log on the andirons; the room sang with the sudden hiss of escaping wood gases. After a little the back of the log caught fire; jets of blue flared up here and there with mellow sounds like the lighting of gas-burners in a row, and in a moment a thin sheet of yellow flame wrapped the whole charred log.

Then the shadows moved; not the shadows behind the furniture – they never moved – but other shadows, thin, gray, confusing, that came and spread their slim patterns all around him, and trembled and trembled.

He dared not step or tread upon them, they were too real; they meshed the floor around his feet, they ensnared his knees, they fell across his breast like ropes. Some night, in the silence of the moors, when wind and river were still, he feared these strands of shadow might tighten – creep higher around his throat and tighten. But even then he knew that those other shadows would never move, those gray shapes that knelt crouching in every corner.

When he looked up at the clock again ten minutes had struggled past. Time was disturbed in the room; the strands of shadow seemed entangled among the hands of the clock, dragging them back from their rotation. He wondered if the shadows would strangle Time, some still night when the wind and the flat river were silent.

There grew a sudden chill across the floor; the cracks of the boards let it in. He leaned down and drew his sabots towards him from their place near the andirons, and slipped them over his chaussons; and as he straightened up, his eyes mechanically sought the mantel above, where in the dusk another pair of sabots stood, little slender, delicate sabots, carved from red beech. A year’s dust grayed their surface; a year’s rust dulled the silver band across the instep. He said this to himself aloud, knowing that it was within a few minutes of the year.

His own sabots came from Mort-Dieu; they were shaved square and banded with steel. But in days past he had thought that no sabot in Mort-Dieu was delicate enough to touch the instep of the Mort-Dieu passeur. So he sent to the shore light-house, and they sent to Lorient, where the women are coquettish and show their hair under the coiffe, and wear dainty sabots; and in this town, where vanity corrupts and there is much lace on coiffe and collarette, a pair of delicate sabots was found, banded with silver and chiselled in red beech. The sabots stood on the mantel above the fire now, dusty and tarnished.

There was a sound from the window, the soft murmur of snow blotting glass panes. The wind, too, muttered under the eaves. Presently it would begin to whisper to him from the chimney – he knew it – and he held his hands over his ears and stared at the clock.

In the hamlet of Mort-Dieu the panes sing all day of the sea secrets, but in the night the ghosts of little gray birds fill the branches, singing of the sunshine of past years. He heard the song as he sat, and he crushed his hands over his ears; but the gray birds joined with the wind in the chimney, and he heard all that he dared not hear, and he thought all that he dared not hope or think, and the swift tears scalded his eyes.

In Mort-Dieu the nights are longer than anywhere on earth; he knew it – why should he not know? This had been so for a year; it was different before. There were so many things different before; days and nights vanished like minutes then; the pines told no secrets of the sea, and the gray birds had not yet come to Mort-Dieu. Also, there was Jeanne, passeur at the Carmes.

When he first saw her she was poling the square, flat-bottomed ferry-skiff from the Carmes to Mort-Dieu, a red skirt fluttering just below her knees. The next time he saw her he had to call to her across the placid river, ‘Ohé! Ohé! passeur!’ She came, poling that flat skiff, her deep blue eyes fixed pensively on him, the scarlet skirt and kerchief idly flapping in the April wind. Then day followed day when the far call ‘Passeur!’ grew clearer and more joyous, and the faint answering cry, ‘I come!’ rippled across the water like music tinged with laughter. Then spring came, and with spring came love – love, carried free across the ferry from the Carmes to Mort-Dieu.

The flame above the charred log whistled, flickered, and went out in a jet of wood vapour, only to play like lightning above the gas and relight again. The clock ticked more loudly, and the song from the pines filled the room. But in his straining eyes a summer landscape was reflected, where white clouds sailed and white foam curled under the square bow of a little skiff. And he pressed his numbed hands tighter to his ears to drown the cry, ‘Passeur! Passeur!’

And now for a moment the clock ceased ticking. It was time to go – who but he should know it, he who went out into the night swinging his lantern? And he went. He had gone each night from the first – from that first strange winter evening when a strange voice answered him across the river, the voice of the new passeur. He had never heard her voice again.

So he passed down the windy wooden stairs, lantern hanging lighted in his hand, and stepped out into the storm. Through sheets of drifting snow, over heaps of frozen seaweed and icy drift he moved, shifting his lantern right and left, until its glimmer on the water warned him. Then he called out into the night, ‘Passeur!’ The frozen spray spattered his face and crusted the lantern; he heard the distant boom of breakers beyond the bar, and the noise of mighty winds among the seaward cliffs.

‘Passeur!’

Across the broad flat river, black as a sea of pitch, a tiny light sparkled a moment. Again he cried, ‘Passeur!’

‘I come!’

He turned ghastly white, for it was her voice – or was he crazy? – and he sprang waist deep into the icy current and cried out again, but his voice ended in a sob.

Slowly through the snow the flat skiff took shape, creeping nearer and nearer. But she was not at the pole – he saw that; there was a tall, thin man, shrouded to his eyes in oilskin; and he leaped into the boat and bade the ferryman hasten.

Halfway across he rose in the skiff, and called, ‘Jeanne!’ But the roar of the storm and the thrashing of the icy waves drowned his voice. Yet he heard her again, and she called to him by name.

When at last the boat grated upon the invisible shore, he lifted his lantern, stumbling among the rocks, and calling to her, as though his voice could silence the voice that had spoken a year ago that night. And it could not. He sank shivering upon his knees, and looked out into the darkness, where an ocean rolled across a world. Then his stiff lips moved, and he repeated her name, but the hand of the ferryman fell gently upon his head.

And when he raised his eyes he saw that the ferryman was Death.

IN THE COURT OF THE DRAGON

‘Oh Thou who burn’st in heart for those who burn

In Hell, whose fires thyself shall feed in turn;

How long be crying, “Mercy on them, God!”

Why, who are thou to teach and He to learn?’

In the Church of St Barnabé vespers were over; the clergy left the altar; the little choir-boys flocked across the chancel and settled in the stalls. A Suisse in rich uniform marched down the south aisle, sounding his staff at every fourth step on the stone pavement; behind him came that eloquent preacher and good man, Monseigneur C—.

My chair was near the chancel rail. I now turned toward the west end of the church. The other people between the altar and the pulpit turned too. There was a little scraping and rustling while the congregation seated itself again; the preacher mounted the pulpit stairs, and the organ voluntary ceased.

I had always found the organ-playing at St Barnabé highly interesting. Learned and scientific it was, too much so for my small knowledge, but expressing a vivid if cold intelligence. Moreover, it possessed the French quality of taste; taste reigned supreme, self-controlled, dignified and reticent.

Today, however, from the first choir I had felt a change for the worse, a sinister change. During vespers it had been chiefly the chancel organ which supported the beautiful choir, but now and again, quite wantonly as it seemed, from the west gallery where the great organ stands, a heavy hand had struck across the church, at the serene peace of those clear voices. It was something more than harsh and dissonant, and it betrayed no lack of skill. As it recurred again and again, it set me thinking of what my architect’s books say about the custom in early times to consecrate the choir as soon as it was built, and that the nave, being finished sometimes half a century later, often did not get any blessing at all: I wondered idly if that had been the case at St Barnabé, and whether something not usually supposed to be at home in a Christian church, might have entered undetected, and taken possession of the west gallery. I had read of such things happening too, but not in works on architecture.

Then I remembered that St Barnabé was not much more than a hundred years old, and smiled at the incongruous association of mediaeval superstitions with that cheerful little piece of eighteenth century rococo.

But now vespers were over, and there should have followed a few quiet chords, fit to accompany meditation, while we waited for the sermon. Instead of that, the discord at the lower end of the church broke out with the departure of the clergy, as if now nothing could control it.

I belong to those children of an older and simpler generation, who do not love to seek for psychological subtleties in art; and I have ever refused to find in music anything more than melody and harmony, but I felt that in the labyrinth of sounds now issuing from that instrument there was something being hunted. Up and down the pedals chased him, while the manuals blared approval. Poor devil! whoever he was there seemed small hope of escape!

My nervous annoyance changed to anger. Who was doing this? How dare he play like that in the midst of divine service? I glanced at the people near me: not one appeared to be in the least disturbed. The placid brows of the kneeling nuns, still turned toward the altar, lost none of their devout abstraction, under the pale shadow of their white head-dress. The fashionable lady beside me was looking expectantly at Monseigneur C—. For all her face betrayed, the organ might have been singing an Ave Maria.

But now, at last, the preacher had made the sign of the cross, and commanded silence. I turned to him gladly. Thus far I had not found the rest I had counted on, when I entered St Barnabé that afternoon.

I was worn out by three nights of physical suffering and mental trouble: the last had been the worst, and it was an exhausted body, and a mind benumbed and yet acutely sensitive, which I had brought to my favorite church for healing. For I had been reading ‘The King in Yellow’.

‘The sun ariseth; they gather themselves together and lay them down in their dens.’ Monseigneur C – delivered his text in a calm voice, glancing quietly over the congregation. My eyes turned, I knew not why, toward the lower end of the church. The organist was coming from behind his pipes, and passing along the gallery on his way out, I saw him disappear by a small door that leads to some stone stairs which descend directly to the street. He was a slender man, and his face was as white as his coat was black. ‘Good riddance!’ I thought, ‘with your wicked music! I hope your assistant will play the closing voluntary.’

With a feeling of relief, with a deep calm feeling of relief, I turned back to the mild face in the pulpit, and settled myself to listen. Here at last was the ease of mind I longed for.

‘My children,’ said the preacher, ‘one truth the human soul finds hardest of all to learn; that it has nothing to fear. It can never be made to see that nothing can really harm it.’

‘Curious doctrine!’ I thought, ‘for a Catholic priest. Let us see how he will reconcile that with the Fathers.’

‘Nothing can really harm the soul,’ he went on, in his coolest, clearest tones, ‘because—’

But I never heard the rest; my eye left his face, I knew not for what reason, and sought the lower end of the church. The same man was coming out from behind the organ, and was passing along the gallery the same way. But there had not been time for him to return, and if he had returned, I must have seen him. I felt a faint chill, and my heart sank; and yet, his going and coming were no affair of mine. I looked at him: I could not look away from his black figure and his white face. When he was exactly opposite to me, he turned and sent across the church, straight into my eyes, a look of hate, intense and deadly: I have never seen any other like it; would to God I might never see it again! Then he disappeared by the same door through which I had watched him depart less than sixty seconds before.

I sat and tried to collect my thoughts. My first sensation was like that of a very young child badly hurt, when it catches its breath before crying out.

To suddenly find myself the object of such hatred was exquisitely painful: and this man was an utter stranger. Why should he hate me so? Me, whom he had never seen before? For the moment all other sensation was merged in this one pang; even fear was subordinate to grief, and for that moment I never doubted; but in the next I began to reason, and a sense of the incongruous came to my aid.

As I have said, St Barnabé is a modern church. It is small and well lighted; one sees all over it almost at a glance. The organ gallery gets a strong white light from a row of long windows in the clerestory, which have not even colored glass.

The pulpit being in the middle of the church, it followed that, when I was turned toward it, whatever moved at the west end could not fail to attract my eye. When the organist passed it was no wonder that I saw him; I had simply miscalculated the interval between his first and his second passing. He had come in that last time by the other side-door. As for the look which had so upset me, there had been no such thing, and I was a nervous fool.

I looked about. This was a likely place to harbor supernatural horrors! That clear-cut, reasonable face of Monseigneur C—, his collected manner, and easy, graceful gestures, were they not just a little discouraging to the notion of a gruesome mystery? I glanced above his head, and almost laughed. That flyaway lady, supporting one corner of the pulpit canopy, which looked like a fringed damask table-cloth in a high wind, at the first attempt of a basilisk to pose up there in the organ loft, she would point her gold trumpet at him, and puff him out of existence! I laughed to myself over this conceit, which, at the time, I thought very amusing, and sat and chaffed myself and everything else, from the old harpy outside the railing, who had made me pay ten centimes for my chair, before she would let me in (she was more like a basilisk, I told myself, than was my organist with the anaemic complexion): from that grim old dame, to, yes, alas! to Monseigneur C— himself. For all devoutness had fled. I had never yet done such a thing in my life, but now I felt a desire to mock.