Полная версия

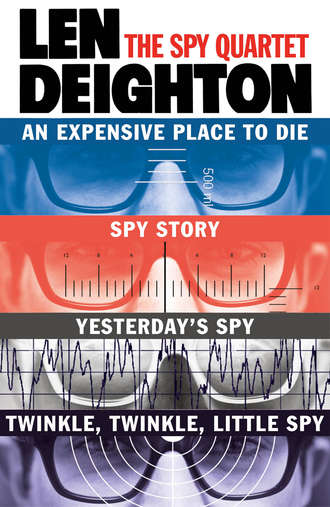

The Spy Quartet: An Expensive Place to Die, Spy Story, Yesterday’s Spy, Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy

‘All good stuff,’ I said. ‘You should be doing my job.’

He smiled and shook his head. ‘How I’d hate that,’ he said. ‘Dealing with the French all day; it’s bad enough having to mix with them in the evening.’

‘The French are all right,’ I said.

‘Did you keep the envelopes? I’ve brought the iodine in pot iodide.’ I gave him all the envelopes that had come through the post during the previous week and he took his little bottle and painted the flaps carefully.

‘Resealed with starch paste. Every damn letter. Someone here, must be. The landlady. Every damned letter. That’s too thorough to be just nosiness. Prenez garde.’ He put the envelopes, which had brown stains from the chemical reaction, into his case. ‘Don’t want to leave them around.’

‘No,’ I said. I yawned.

‘I don’t know what you do all day,’ he said. ‘Whatever do you find to do?’

‘I do nothing all day except make coffee for people who wonder what I do all day.’

‘Yes, well thanks for lunch. The old bitch does a good lunch even if she does steam your mail open.’ He poured both of us more coffee. ‘There’s a new job for you.’ He added the right amount of sugar, handed it to me and looked up. ‘A man named Datt who comes here to Le Petit Légionnaire. The one that was sitting opposite us at lunch today.’ There was a silence. I said:

‘What do you want to know about him?’

‘Nothing,’ said the courier. ‘We don’t want to know anything about him, we want to give him a caseful of data.’

‘Write his address on it and take it to the post office.’

He gave a pained little grimace. ‘It’s got to sound right when he gets it.’

‘What is it?’

‘It’s a history of nuclear fall-out, starting from New Mexico right up to the last test. There are reports from the Hiroshima hospital for bomb victims and various stuff about its effect upon cells and plant-life. It’s too complex for me but you can read it through if your mind works that way.’

‘What’s the catch?’

‘No catch.’

‘What I need to know is how difficult it is to detect the phoney parts. One minute in the hands of an expert? Three months in the hands of a committee? I need to know how long the fuse is, if I’m the one that’s planting the bomb.’

‘There is no cause to believe it’s anything other than genuine.’ He pressed the lock on the case as though to test his claim.

‘Well that’s nice,’ I said. ‘Who does Datt send it to?’

‘Not my part of the script, old boy. I’m just the errand boy, you know. I give the case to you, you give it to Datt, making sure he doesn’t know where it came from. Pretend you are working for CIA if you like. You are a clean new boy, it should be straightforward.’

He drummed his fingers to indicate that he must leave.

‘What am I expected to do with your bundle of papers – leave it on his plate one lunchtime?’

‘Don’t fret, that’s being taken care of. Datt will know that you have the documents, he’ll contact you and ask for them. Your job is just to let him have them … reluctantly.’

‘Was I planted in this place six months ago just to do this job?’

He shrugged, and put the leather case on the table.

‘Is it that important?’ I asked. He walked to the door without replying. He opened the door suddenly and seemed disappointed that there was no one crouching outside.

‘Terribly good coffee,’ he said. ‘But then it always is.’ From downstairs I could hear the pop music on the radio. It stopped. There was a fanfare and a jingle advertising shampoo.

‘This is your floating favourite, Radio Janine,’ said the announcer. It was a wonderful day to be working on one of the pirate radio ships: the sun warm, and three miles of calm blue sea that entitled you to duty-free cigarettes and whisky. I added it to the long list of jobs that were better than mine. I heard the lower door slam as the courier left. Then I washed up the coffee cups, gave Joe some fresh water and cuttlefish bone for his beak, picked up the documents and went downstairs for a drink.

2

Le Petit Légionnaire (‘cuisine faite par le patron’) was a plastic-trimmed barn glittering with mirrors, bottles and pin-tables. The regular lunchtime customers were local businessmen, clerks from a near-by hotel, two German girls who worked for a translation agency, a couple of musicians who slept late every day, two artists and the man named Datt to whom I was to offer the nuclear fall-out findings. The food was good. It was cooked by my landlord who was known throughout the neighbourhood as la voix – a disembodied voice that bellowed up the lift shaft without the aid of a loudspeaker system. La voix – so the stories went – once had his own restaurant in Boul. Mich. which during the war was a meeting place for members of the Front National.1 He almost got a certificate signed by General Eisenhower but when his political past became clearer to the Americans he got his restaurant declared out of bounds and searched by the MPs every week for a year instead.

La voix did not like orders for steck bien cuit, charcuterie as a main dish or half-portions of anything at all. Regular customers got larger meals. Regular customers also got linen napkins but were expected to make them last all the week. But now lunch was over. From the back of the café I could hear the shrill voice of my landlady and the soft voice of Monsieur Datt who was saying, ‘You might be making a mistake, you’ll pay one hundred and ten thousand francs in Avenue Henri Martin and never see it come back.’

‘I’ll take a chance on that,’ said my landlord. ‘Have a little more cognac.’

M. Datt spoke again. It was a low careful voice that measured each word carefully, ‘Be content, my friend. Don’t search for the sudden flashy gain that will cripple your neighbour. Enjoy the smaller rewards that build imperceptibly towards success.’

I stopped eavesdropping and moved on past the bar to my usual table outside. The light haze that so often prefaces a very hot Paris day had disappeared. Now it was a scorcher. The sky was the colour of well-washed bleu de travail. Across it were tiny wisps of cirrus. The heat bit deep into the concrete of the city and outside the grocers’ fruit and vegetables were piled beautifully in their wooden racks, adding their aroma to the scent of a summer day. The waiter with the withered hand sank a secret cold lager, and old men sat outside on the terrasse warming their cold bones. Dogs cocked their legs jauntily and young girls wore loose cotton dresses and very little make-up and fastened their hair with elastic bands.

A young man propped his moto carefully against the wall of the public baths across the road. He reached an aerosol can of red paint from the pannier, shook it and wrote ‘lisez l’Humanite nouvelle’ across the wall with a gentle hiss of compressed air. He glanced over his shoulder, then added a large hammer and sickle. He went back to his moto and sat astride it surveying the sign. A thick red dribble ran down from the capital H. He went back to the wall and dabbed at the excess paint with a piece of rag. He looked around, but no one shouted to him, so he carefully added the accent to the e before wrapping the can into the rag and stowing it away. He kicked the starter, there was a puff of light-blue smoke and the sudden burp of the two-stroke motor as he roared away towards the Boulevard.

I sat down and waved to old Jean for my usual Suze. The pin-table glittered with pop-art-style illuminations and click-clicked and buzzed as the perfect metal spheres touched the contacts and made the numbers spin. The mirrored interior lied about the dimensions of the café and portrayed the sunlit street deep in its dark interior. I opened the case of documents, smoked, read, drank and watched the life of the quartier. I read ninety-three pages and almost understood by the time the rush-hour traffic began to thicken. I hid the documents in my room. It was time to visit Byrd.

I lived in the seventeenth arrondissement. The modernization project that had swept up the Avenue Neuilly and was extending the smart side of Paris to the west had bypassed the dingy Quartier des Ternes. I walked as far as the Avenue de la Grande Armée. The Arc was astraddle the Étoile and the traffic was desperate to get there. Thousands of red lights twinkled like bloodshot stars in the warm mist of the exhaust fumes. It was a fine Paris evening, Gauloises and garlic sat lightly on the air, and the cars and people were moving with the subdued hysteria that the French call élan.

I remembered my conversation with the man from the British Embassy. He seemed upset today, I thought complacently. I didn’t mind upsetting him. Didn’t mind upsetting all of them, come to that. No cause to believe it’s anything other than genuine. I snorted loudly enough to attract attention. What a fool London must think I am. And that stuff about Byrd. How did they know I’d be dining with him tonight? Byrd, I thought, art books from Skira, what a lot of cock. I hardly knew Byrd, even though he was English and did lunch in Le Petit Légionnaire. Last Monday I dined with him but I’d told no one that I was dining with him again tonight. I’m a professional. I wouldn’t tell my mother where I keep the fuse wire.

3

The light was just beginning to go as I walked through the street market to Byrd’s place. The building was grey and peeling, but so were all the others in the street. So, in fact, were almost all the others in Paris. I pressed the latch. Inside the dark entrance a twenty-five-watt bulb threw a glimmer of light across several dozen tiny hutches with mail slots. Some of the hutches were marked with grimy business cards, others had names scrawled across them in ball-point writing. Down the hall there were thick ropes of wiring connected to twenty or more wooden boxes. Tracing a wiring fault would have proved a remarkable problem. Through a door at the far end there was a courtyard. It was cobbled, grey and shiny with water that dripped from somewhere overhead. It was a desolate yard of a type that I had always associated with the British prison system. The concierge was standing in the courtyard as though daring me to complain about it. If mutiny came, then that courtyard would be its starting place. At the top of a narrow creaking staircase was Byrd’s studio. It was chaos. Not the sort of chaos that results from an explosion, but the kind that takes years to achieve. Spend five years hiding things, losing things and propping broken things up, then give it two years for the dust to settle thickly and you’ve got Byrd’s studio. The only really clean thing was the gigantic window through which a sunset warmed the whole place with rosy light. There were books everywhere, and bowls of hardened plaster, buckets of dirty water, easels carrying large half-completed canvases. On the battered sofa were the two posh English Sunday papers still pristine and unread. A huge enamel-topped table that Byrd used as a palette was sticky with patches of colour, and across one wall was a fifteen-foot-high hardboard construction upon which Byrd was painting a mural. I walked straight in – the door was always open.

‘You’re dead,’ called Byrd loudly. He was high on a ladder working on a figure near the top of the fifteen-foot-high painting.

‘I keep forgetting I’m dead,’ said the model. She was nude and stretched awkwardly across a box.

‘Just keep your right foot still,’ Byrd called to her. ‘You can move your arms.’

The nude girl stretched her arms with a grateful moan of pleasure.

‘Is that okay?’ she asked.

‘You’ve moved the knee a little, it’s tricky … Oh well, perhaps we’ll call that a day.’ He stopped painting. ‘Get dressed, Annie.’ She was a tall girl of about twenty-five. Dark, good-looking, but not beautiful. ‘Can I have a shower?’ she asked.

‘The water’s not too warm, I’m afraid,’ said Byrd, ‘but try it, it may have improved.’

The girl pulled a threadbare man’s dressing-gown around her shoulders and slid her feet into a pair of silk slippers. Byrd climbed very slowly down from the ladder on which he was perched. There was a smell of linseed oil and turpentine. He rubbed at the handful of brushes with a rag. The large painting was nearly completed. It was difficult to put a name to the style; perhaps Kokoschka or Soutine came nearest to it but this was more polished, though less alive, than either. Byrd tapped the scaffolding against which the ladder was propped.

‘I built that. Not bad, eh? Couldn’t get one like it anywhere in Paris, not anywhere. Are you a do-it-yourself man?’

‘I’m a let-someone-else-do-it man.’

‘Really,’ said Byrd and nodded gravely. ‘Eight o’clock already, is it?’

‘Nearly half past,’ I said.

‘I need a pipe of tobacco.’ He threw the brushes into a floral-patterned chamber-pot in which stood another hundred. ‘Sherry?’ He untied the strings that prevented his trouser bottoms smudging the huge painting, and looked back towards the mural, hardly able to drag himself away from it. ‘The light started to go an hour back. I’ll have to repaint that section tomorrow.’ He took the glass from an oil lamp, lit the wick carefully and adjusted the flame. ‘A fine light these oil lamps give. A fine silky light.’ He poured two glasses of dry sherry, removed a huge Shetland sweater and eased himself into a battered chair. In the neck of his check-patterned shirt he arranged a silk scarf, then began to sift through his tobacco pouch as though he’d lost something in there.

It was hard to guess Byrd’s age except that he was in the middle fifties. He had plenty of hair and it was showing no sign of grey. His skin was fair and so tight across his face that you could see the muscles that ran from cheekbone to jaw. His ears were tiny and set high, his eyes were bright, active and black, and he stared at you when he spoke to prove how earnest he was. Had I not known that he was a regular naval officer until taking up painting eight years ago I might have guessed him to be a mechanic who had bought his own garage. When he had carefully primed his pipe he lit it with slow care. It wasn’t until then that he spoke again.

‘Go to England at all?’

‘Not often,’ I said.

‘Nor me. I need more baccy; next time you go you might bear that in mind.’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘This brand,’ he held a packet for me to see. ‘Don’t seem to have it here in France. Only stuff I like.’

He had a stiff, quarter-deck manner that kept his elbows at his waist and his chin in his neck. He used words like ‘roadster’ that revealed how long it was since he had lived in England.

‘I’m going to ask you to leave early tonight,’ he said. ‘Heavy day tomorrow.’ He called to the model, ‘Early start tomorrow, Annie.’

‘Very well,’ she called back.

‘We’ll call dinner off if you like.’ I offered.

‘No need to do that. Looking forward to it to tell the truth.’ Byrd scratched the side of his nose.

‘Do you know Monsieur Datt?’ I asked. ‘He lunches at the Petit Légionnaire. Big-built man with white hair.’

‘No,’ he said. He sniffed. He knew every nuance of the sniff. This one was light in weight and almost inaudible. I dropped the subject of the man from the Avenue Foch.

Byrd had asked another painter to join us for dinner. He arrived about nine thirty. Jean-Paul Pascal was a handsome muscular young man with a narrow pelvis who easily adapted himself to the cowboy look that the French admire. His tall rangy figure contrasted sharply with the stocky blunt rigidity of Byrd. His skin was tanned, his teeth perfect. He was expensively dressed in a light-blue suit and a tie with designs embroidered on it. He removed his dark glasses and put them in his pocket.

‘An English friend of Monsieur Byrd,’ Jean-Paul repeated as he took my hand and shook it. ‘Enchanted.’ His handshake was gentle and diffident as though he was ashamed to look so much like a film star.

‘Jean-Paul speaks no English,’ said Byrd.

‘It is too complicated,’ said Jean-Paul. ‘I speak a little but I do not understand what you say in reply.’

‘Precisely,’ said Byrd. ‘That’s the whole idea of English. Foreigners can communicate information to us but Englishmen can still talk together without an outsider being able to comprehend.’ His face was stern, then he smiled primly. ‘Jean-Paul’s a good fellow just the same: a painter.’ He turned to him. ‘Busy day, Jean?’

‘Busy, but I didn’t get much done.’

‘Must keep at at, my boy. You’ll never be a great painter unless you learn to apply yourself.’

‘Oh but one must find oneself. Proceed at one’s own speed,’ said Jean-Paul.

‘Your speed is too slow,’ Byrd pronounced, and handed Jean-Paul a glass of sherry without having asked him what he wanted. Jean turned to me, anxious to explain his apparent laziness. ‘It is difficult to begin a painting – it’s a statement – once the mark is made one has to relate all later brush-strokes to it.’

‘Nonsense,’ said Byrd. ‘Simplest thing in the world to begin, tricky though pleasurable to proceed with, but difficult – dammed difficult – to end.’

‘Like a love affair,’ I said. Jean laughed. Byrd flushed and scratched the side of his nose.

‘Ah. Work and women don’t mix. Womanizing and loose living is attractive at the time, but middle age finds women left sans beauty, and men sans skills; result misery. Ask your friend Monsieur Datt about that.’

‘Are you a friend of Datt?’ Jean-Paul asked.

‘I hardly know him,’ I said. ‘I was asking Byrd about him.’

‘Don’t ask too many questions,’ said Jean. ‘He is a man of great influence; Count of Périgord it is said, an ancient family, a powerful man. A dangerous man. He is a doctor and a psychiatrist. They say he uses LSD a great deal. His clinic is as expensive as any in Paris, but be gives the most scandalous parties there too.’

‘What’s that?’ said Byrd. ‘Explain.’

‘One hears stories,’ said Jean. He smiled in embarrassment and wanted to say no more, but Byrd made an impatient movement with his hand, so he continued. ‘Stories of gambling parties, of highly placed men who have got into financial trouble and found themselves …’ he paused ‘… in the bath.’

‘Does that mean dead?’

‘It means “in trouble”, idiom,’ explained Byrd to me in English.

‘One or two important men took their own lives,’ said Jean. ‘Some said they were in debt.’

‘Damned fools,’ said Byrd. ‘That’s the sort of fellows in charge of things today, no stamina, no fibre; and that fellow Datt is a party to it, eh? Just as I thought. Oh well, chaps won’t be told today. Experience better bought than taught they say. One more sherry and we’ll go to dinner. What say to La Coupole? It’s one of the few places still open where we don’t have to reserve.’

Annie the model reappeared in a simple green shirtwaist dress. She kissed Jean-Paul in a familiar way and said good evening to each of us.

‘Early in the morning,’ Byrd said as he paid her. She nodded and smiled.

‘An attractive girl,’ Jean-Paul said after she had gone.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Poor child,’ said Byrd. ‘It’s a hard town for a young girl without money.’

I’d noticed her expensive crocodile handbag and Charles Jourdan shoes, but I didn’t comment.

‘Want to go to an art show opening Friday? Free champagne.’ Jean-Paul produced half a dozen gold-printed invitations, gave one to me and put one on Byrd’s easel.

‘Yes, we’ll go to that,’ said Byrd; he was pleased to be organizing us. ‘Are you in your fine motor, Jean?’ Byrd asked.

Jean nodded.

Jean’s car was a white Mercedes convertible. We drove down the Champs with the roof down. We wined and dined well and Jean-Paul plagued us with questions like do the Americans drink Coca-Cola because it’s good for their livers.

It was nearly one A.M. when Jean dropped Byrd at the studio. He insisted upon driving me back to my room over Le Petit Légionnaire. ‘I am especially glad you came tonight,’ he said. ‘Byrd thinks that he is the only serious painter in Paris, but there are many of us who work equally hard in our own way.’

‘Being in the navy,’ I said, ‘is probably not the best of training for a painter.’

‘There is no training for a painter. No more than there is training for life. A man makes as profound a statement as he is able. Byrd is a sincere man with a thirst for knowledge of painting and an aptitude for its skills. Already his work is attracting serious interest here in Paris and a reputation in Paris will carry you anywhere in the world.’

I sat there for a moment nodding, then I opened the door of the Mercedes and got out. ‘Thanks for the ride.’

Jean-Paul leaned across the seat, offered me his card and shook my hand. ‘Phone me,’ he said, and – without letting go of my hand – added, ‘If you want to go to the house in the Avenue Foch I can arrange that too. I’m not sure I can recommend it, but if you have money to lose I’ll introduce you. I am a close friend of the Count; last week I took the Prince of Besacoron there – he is another very good friend of mine.’

‘Thanks,’ I said, taking the card. He stabbed the accelerator and the motor growled. He winked and said, ‘But no recriminations afterward.’

‘No,’ I agreed. The Mercedes slid forward.

I watched the white car turn on to the Avenue with enough momentum to make the tyres howl. The Petit Légionnaire was closed. I let myself in by the side entrance. Datt and my landlord were still sitting at the same table as they had been that afternoon. They were still playing Monopoly. Datt was reading from his Community Chest card, ‘Allez en prison. Avancez tout droit en prison. Ne passez pas par la case “Départ”. Ne recevez pas Frs 20.000.’ My landlord laughed, so did M. Datt.

‘What will your patients say?’ said my landlord.

‘They are very understanding,’ said Datt; he seemed to take the whole game seriously. Perhaps he got more out of it that way.

I tiptoed upstairs. I could see right across Paris. Through the dark city the red neon arteries of the tourist industry flowed from Pigalle through Montmartre to Boul. Mich., Paris’s great self-inflicted wound.

Joe chirped. I read Jean’s card. ‘“Jean-Paul Pascal, artist painter”. And good friend to princes,’ I said. Joe nodded.

4

Two nights later I was invited to join the Monopoly game. I bought hotels in rue Lecourbe and paid rent at the Gare du Nord. Old Datt pedantically handled the toy money and told us why we went broke.

When only Datt remained solvent he pushed back his chair and nodded sagely as he replaced the pieces of wood and paper in the box. If you were buying old men, then Datt would have come in a box marked White, Large and Bald. Behind his tinted spectacles his eyes were moist and his lips soft and dark like a girl’s, or perhaps they only seemed dark against the clear white skin of his face. His head was a shiny dome and his white hair soft and wispy like mist around a mountain top. He didn’t smile much, but he was a genial man, although a little fussy in his mannerisms as people of either sex become when they live alone.

Madame Tastevin had, upon her insolvency, departed to the kitchen to prepare supper.

I offered my cigarettes to Datt and to my landlord. Tastevin took one, but Datt declined with a theatrical gesture. ‘There seems no sense in it,’ he proclaimed, and again did that movement of the hand that looked like he was blessing a multitude at Benares. His voice was an upper-class voice, not because of his vocabulary or because he got his conjugations right but because he sang his words in the style of the Comédie Française, stressing a word musically and then dropping the rest of the sentence like a half-smoked Gauloise. ‘No sense in it,’ he repeated.

‘Pleasure,’ said Tastevin, puffing away. ‘Not sense.’ His voice was like a rusty lawn-mower.

‘The pursuit of pleasure,’ said Datt, ‘is a pitfall-studded route.’ He removed the rimless spectacles and looked up at me blinking.