полная версия

полная версияThe Rifle and the Hound in Ceylon

'Bran,' a perfect model of a greyhound.

'Lucifer,' combining the beauty, speed, and courage of his parents, 'Bran' and ' Lena,' in a superlative degree.

There are many others that I could call from the pack and introduce as first-rate hounds, but as no jealousy will be occasioned by their omission, I shall be contented with those already named.

Were I to recount the twentieth part of the scenes that I have witnessed in this sport, it would fill a volume, and become very tedious. A few instances related will at once explain the whole character of the sport, and introduce a stranger to the wild hunts of the Ceylon mountains.

I have already described Newera Ellia, with its alternate plains and forests, its rapid streams and cataracts, its mountains, valleys, and precipices; but a portion of this country, called the Horton Plains, will need a further description.

Some years ago I hunted with a brother Nimrod, Lieutenant de Montenach, of the 15th Regiment, in this country; and in two months we killed forty-three elk.

The Horton Plains are about twenty miles from Newera Ellia. After a walk of sixteen miles through alternate plains and forests, the steep ascent of Totapella mountain is commenced by a rugged path through jungle the whole way. So steep is the track that a horse ascends with difficulty, and riding is of course impossible. After a mile and a quarter of almost perpendicular scrambling, the summit of the pass is reached, commanding a splendid view of the surrounding country, and Newera Ellia can be seen far beneath in the distance. Two miles farther on, after a walk through undulating forest, the Horton Plains burst suddenly upon the view as you emerge from the jungle path. These plains are nearly 800 feet higher than Newera Ellia, or 7,000 feet above the sea. The whole aspect of the country appears at once to have assumed a new character; there is a feeling of being on the top of everything, and instead of a valley among surrounding hills, which is the feature of Newera Ellia and the adjacent plains, a beautiful expanse of flat table-land stretches before the eye, bounded by a few insignificant hill-tops. There is a peculiar freedom in the Horton Plains, an absence from everywhere, a wildness in the thought that there is no tame animal within many miles, not a village, nor hut, nor human being. It makes a man feel in reality one of the 'lords of the creation' when he first stands upon this elevated plain, and, breathing the pure thin air, he takes a survey of his hunting-ground: no boundaries but mountain tops and the horizon; no fences but the trunks of decayed trees fallen from old age; no game laws but strong legs, good wind, and the hunting-knife; no paths but those trodden by the elk and elephant. Every nook and corner of this wild country is as familiar to me as my own garden. There is not a valley that has not seen a burst in full cry; not a plain that has not seen the greyhounds in full speed after an elk; and not a deep pool in the river that has not echoed with a bay that has made the rocks ring again.

To give a person an interest in the sport, the country must be described minutely. The plain already mentioned as the flat table-land first seen on arrival, is about five miles in length, and two in breadth in the widest part. This is tolerably level, with a few gentle undulations, and is surrounded, on all sides but one, with low, forest-covered slopes. The low portions of the plains are swamps, from which springs a large river, the source of the Mahawelli Ganga.

From the plain now described about fifteen others diverge, each springing from the parent plain, and increasing in extent as they proceed; these are connected more or less by narrow valleys, and deep ravines. Through the greater portion of these plains, the river winds its wild course. In the first a mere brook, it rapidly increases as it traverses the lower portions of every valley, until it attains a width of twenty or thirty yards, within a mile of the spot where it is first discernible as a stream. Every plain in succession being lower than the first, the course of the river is extremely irregular; now a maze of tortuous winding, then a broad, still stream, bounded by grassy undulations; now rushing wildly through a hundred channels formed by obtruding rocks, then in a still, deep pool, gathering itself together for a mad leap over a yawning precipice, and roaring at a hundred feet beneath, it settles in the lower plain in a pool of unknown depth; and once more it murmurs through another valley.

In the large pools formed by the sudden turns in the river, the elk generally takes his last determined stand, and he sometimes keeps dogs and men at bay for a couple of hours. These pools are generally about sixty yards across, very deep in some parts, with a large shallow sandbank in the centre, formed by the eddy of the river.

We built a hunting bivouac in a snug corner of the plains, which gloried in the name of 'Elk Lodge.' This famous hermitage was a substantial building, and afforded excellent accommodation: a verandah in the front, twenty-eight feet by eight; a dining-room twenty feet by twelve, with a fireplace eight feet wide; and two bed-rooms of twenty feet by eight. Deer-hides were pegged down to form a carpet upon the floors, and the walls were neatly covered with talipot leaves. The outhouses consisted of the kennel, stables for three horses, kitchen, and sheds for twenty coolies and servants.

The fireplace was a rough piece of art, upon which we prided ourselves extremely. A party of eight persons could have sat before it with comfort. Many a roaring fire has blazed up that rude chimney; and dinner being over, the little round table before the hearth has steamed forth a fragrant attraction, when the nightly bowl of mulled port has taken its accustomed stand. I have spent many happy hours in this said spot; the evenings were of a decidedly social character. The day's hunting over, it was a delightful hour at about seven P.M.—dinner just concluded, the chairs brought before the fire, cigars and the said mulled port. Eight o'clock was the hour for bed, and five in the morning to rise, at which time a cup of hot tea, and a slice of toast and anchovy paste were always ready before the start. The great man of our establishment was the cook.

This knight of the gridiron was a famous fellow, and could perform wonders; of stoical countenance, he was never seen to smile. His whole thoughts were concentrated in the mysteries of gravies, and the magic transformation of one animal into another by the art of cookery; in this he excelled to a marvellous degree. The farce of ordering dinner was always absurd. It was something in this style: 'Cook!' (Cook answers) 'Coming, sar!' (enter cook): 'Now, cook, you make a good dinner; do you hear?' Cook: 'Yes, sar; master tell, I make.'—'Well, mulligatawny soup.' 'Yes, sar.'—'Calves' head with tongue and brain sauce.' 'Yes, sar.'—' Gravy omelette.' 'Yes, sar.'—'Mutton chops.' 'Yes, sar.'—'Fowl cotelets.' 'Yes, sar.'—'Beefsteaks.' 'Yes, sar.'—'Marrow-bones.' 'Yes, sar.'—'Rissoles.' 'Yes, sar.' All these various dishes he literally imitated uncommonly well, the different portions of an elk being their only foundation.

The kennel bench was comfortably littered, and the pack took possession of their new abode with the usual amount of growling and quarrelling for places; the angry grumbling continuing throughout the night between the three champions of the kennel—Smut, Bran, and Killbuck. After a night much disturbed by this constant quarrelling, we unkennelled the hounds just as the first grey streak of dawn spread above Totapella Peak.

The mist was hanging heavily on the lower parts of the plain like a thick snowbank, although the sky was beautifully clear above, in which a few pale stars still glimmered. Long lines of fog were slowly drifting along the bottoms of the valleys, dispelled by a light breeze, and day fast advancing bid fair for sport; a heavy dew lay upon the grass, and we stood for some moments in uncertainty as to the first point of our extensive hunting-grounds that we should beat. There were fresh tracks of elk close to our 'lodge,' who had been surveying our new settlement during the night. Crossing the river by wading waist-deep, we skirted along the banks, winding through a narrow valley with grassy hills capped with forest upon either side. Our object in doing this was to seek for marks where the elk had come down to drink during the night, as we knew that the tracks would then lead to the jungle upon either side the river. We had strolled quietly along for about half a mile, when the loud bark of an elk was suddenly heard in the jungle upon the opposite hills. In a moment the hounds dashed across the river towards the well-known sound, and entered the jungle at full speed. Judging the direction which the elk would most probably take when found, I ran along the bank of the river, down stream, for a quarter of a mile, towards a jungle through which the river flowed previous to its descent into the lower plains, and I waited, upon a steep grassy hill, about a hundred feet above the river's bed. From this spot I had a fine view of the ground. Immediately before me, rose the hill from which the elk had barked; beneath my feet, the river stretched into a wide pool on its entrance to the jungle. This jungle clothed the precipitous cliffs of a deep ravine, down which the river fell in two cataracts; these were concealed from view by the forest. I waited in breathless expectation of 'the find.' A few minutes passed, when the sudden burst of the pack in full cry came sweeping down upon the light breeze; loudly the cheering sound swelled as they topped the hill, and again it died away as they crossed some deep ravine. In a few minutes the cry became very distant; as the elk was evidently making straight up the hills; once or twice I feared he would cross them, and make away for a different part of the country. The cry of the pack was so indistinct that my ear could barely catch it, when suddenly a gust of wind from that direction brought down a chorus of voices that there was no mistaking: louder and louder the music became; the elk had turned, and was coming down the hill-side at a slapping pace. The jungle crashed as he came rushing through the yielding branches. Out he came, breaking cover in fine style, and away he dashed over the open country. He was a noble buck, and had got a long start; not a single hound had yet appeared, but I heard them coming through the jungle in full cry. Down the side of the hill he came straight to the pool beneath my feet. Yoick to him! Hark forward to him! and I gave a view halloa till my lungs had well-nigh cracked. I had lost sight of him, as he had taken to water in the pool within the jungle.

One more halloa! and out came the gallant old fellow Smut from the jungle, on the exact line that the elk had taken. On he came, bounding along the rough side of the hill like a lion, followed by only two dogs—Dan, a pointer (since killed by a leopard), and Cato, a young dog who had never yet seen an elk. The remainder of the pack had taken after a doe that had crossed the scent, and they were now running in a different direction. I now imagined that the elk had gone down the ravine to the lower plains by some run that might exist along the edge of the cliff, and accordingly I started off along a deer-path through the jungle, to arrive at the lower plains by the shortest road that I could make.

Hardly had I run a hundred yards, when I heard the ringing of the bay and the deep voice of Smut, mingled with the roar of the waterfall, to which I had been running parallel. Instantly changing my course, I was in a few moments on the bank of the river just above the fall. There stood the buck at bay in a large pool about three feet deep, where the dogs could only advance by swimming. Upon my jumping into the pool, he broke his bay, and, dashing through the dogs, he appeared to leap over the verge of the cataract, but in reality he took to a deer-path which skirted the steep side of the wooded precipice. So steep was the inclination that I could only follow on his track by clinging to the stems of the trees. The roar of the waterfall, now only a few feet on my right hand, completely overpowered the voices of the dogs wherever they might be, and I carefully commenced a perilous descent by the side of the fall, knowing that both dogs and elk must be somewhere before me. So stunning was the roar of the water, that a cannon might have been fired without my hearing it. I was now one-third of the way down the fall, which was about fifty feet deep. A large flat rock projected from the side of the cliff, forming a platform of about six feet square, over one corner of which, the water struck, and again bounded downwards. This platform could only be reached by a narrow ledge of rock, beneath which, at a depth of thirty feet, the water boiled at the foot of the fall. Upon this platform stood the buck, having gained his secure but frightful position by passing along the narrow ledge of rock. Should either dog or man attempt to advance, one charge from the buck would send them to perdition, as they would fall into the abyss below. This the dogs were fully aware of, and they accordingly kept up a continual bay from the edge of the cliff, while I attempted to dislodge him by throwing stones and sticks upon him from above.

Finding this uncomfortable, he made a sudden dash forward, and, striking the dogs over, away he went down the steep sides of the ravine, followed once more by the dogs and myself.

By clinging from tree to tree, and lowering myself by the tangled creepers, I was soon at the foot of the first fall, which plunged into a deep pool on a flat plateau of rock, bounded on either side by a wall-like precipice.

This plateau was about eighty feet in length, through which, the water flowed in two rapid but narrow streams from the foot of the first fall towards a second cataract at the extreme end. This second fall leaped from the centre of the ravine into the lower plain.

When I arrived on this fine level surface of rock, a splendid sight presented itself. In the centre of one of the rapid streams, the buck stood at bay, belly-deep, with the torrent rushing in foam between his legs. His mane was bristled up, his nostrils were distended, and his antlers were lowered to receive the dog who should first attack him. I happened to have a spear on that occasion, so that I felt he could not escape, and I gave the baying dogs a loud cheer on. Poor Cato! it was his first elk, and he little knew the danger of a buck at bay in such a strong position. Answering with youthful ardour to my halloa, the young dog sprang boldly at the elk's face, but, caught upon the ready antlers, he was instantly dashed senseless upon the rocks. Now for old Smut, the hero of countless battles, who, though pluck to the back-bone, always tempers his valour with discretion.

Yoick to him, Smut! and I jumped into the water. The buck made a rush forward, but at that moment a mass of yellow hair dangled before his eyes as the true old dog hung upon his cheek. Now came the tug of war—only one seizer! The spring had been so great, and the position of the buck was so secure, that the dog had missed the ear, and only held by the cheek. The elk, in an instant, saw his advantage, and quickly thrusting his sharp brown antlers into the dog's chest, he reared to his full height and attempted to pin the apparently fated Smut against a rock. That had been the last of Smut's days of prowess had I not fortunately had a spear. I could just reach the elk's shoulder in time to save the dog. After a short but violent struggle, the buck yielded up his spirit. He was a noble fellow, and pluck to the last.

Having secured his horns to a bush, lest he should be washed away by the torrent, I examined the dogs. Smut was wounded in two places, but not severely, and Cato had just recovered his senses, but was so bruised as to move with great difficulty. In addition to this, he had a deep wound from the buck's horn under the shoulder.

The great number of elk at the Horton plains and the open character of the country, make the hunting a far more enjoyable sport than it is in Newera Ellia, where the plains are of much smaller extent, and the jungles are frightfully thick. During a trip of two months at the Horton Plains, we killed forty-three elk, exclusive of about ten which the pack ran into and killed by themselves, bringing home the account of their performances in distended stomachs. These occurrences frequently happen when the elk takes away through an impervious country, where a man cannot possibly follow. In such cases the pack is either beaten off, or they pull the elk down and devour it.

This was exemplified some time ago, when the three best dogs were nearly lost. A doe elk broke cover from a small jungle at the Horton Plains, and, instead of taking across the patinas (plains), she doubled back to an immense pathless jungle, closely followed by three greyhounds—Killbuck, Bran, and Lena. The first dog, who ran beautifully by nose, led the way, and their direction was of course unknown, as the dogs were all mute. Night came, and they had not returned. The next day passed away, but without a sign of the missing dogs. I sent natives to search the distant jungles and ravines in all directions. Three days passed away, and I gave up all hope of them. We were sitting at dinner one night, the fire was blazing cheerfully within, but the rain was pouring without, the wind was howling in fitful gusts, and neither moon nor stars relieved the pitchy darkness of the night, when the conversation naturally turned to the lost dogs. What a night for the poor brutes to be exposed to, roaming about the wet jungles without a chance of return!

A sudden knock at the door arrested our attention; it opened. Two natives stood there, dripping with wet and shivering with cold. One had in his hand an elk's head, much gnawed; the other man, to my delight, led the three lost dogs. They had run their elk down, and were found by the side of a rocky river several miles distant—the two dogs asleep in a cave, and the bitch was gnawing the remains of the half-consumed animal. The two men who had found them were soon squatted before a comfortable fire, with a good feed of curry and rice, and their skins full of brandy.

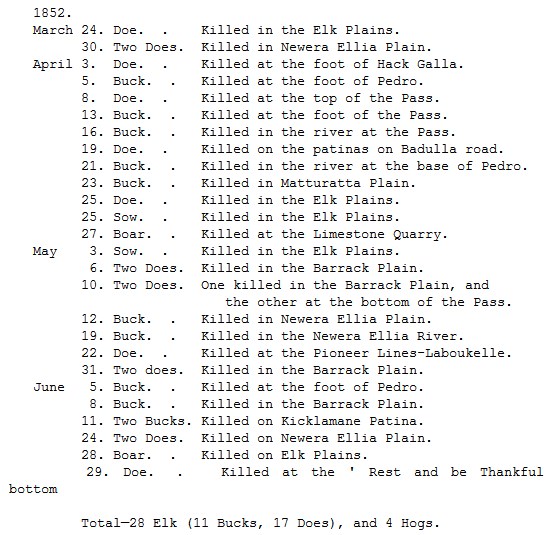

Although the elk are so numerous at the Horton Plains, the sport at length becomes monotonous from the very large proportion of the does. The usual ratio in which they were killed was one buck to eight does. I cannot at all account for this small proportion of bucks in this particular spot. At Newera Ellia they are as two or three compared with the does. The following extract of deaths, taken from my game-book during three months of the year, will give a tolerably accurate idea of the number killed:

This is a tolerable show of game when it is considered that the sport continues from year to year; there are no seasons at which time the game is spared, but the hunting depends simply on the weather. Three times a week the pack turns out in the dry season, and upon every fine day during the wet months. It must appear a frightful extravagance to English ideas to feed the hounds upon venison, but as it costs nothing, it is a cheaper food than beef, and no other flesh is procurable in sufficient quantity. Venison is in its prime when the elk's horns are in velvet. At this season, when the new antlers have almost attained their full growth, they are particularly tender, and the buck moves slowly and cautiously through the jungle, lest he should injure them against the branches, taking no further exercise than is necessary in the search of food. He therefore grows very fat, and is then in fine condition.

The speed of an elk, although great, cannot be compared to that of the spotted deer. I have seen the latter almost distance the best greyhounds for the first 200 yards, but with this class of dogs the elk has no chance upon fair open ground. Coursing the elk, therefore, is a short-lived sport, as the greyhounds run into him immediately, and a tremendous struggle then ensues, which must be terminated as soon as possible by the knife, otherwise the dogs would most probably be wounded. I once saw Killbuck perform a wonderful feat in seizing. A buck elk broke cover in the Elk Plains, and I slipped a brace of greyhounds after him, Killbuck and Bran. The buck had a start of about 200 yards, but the speed of the greyhounds told rapidly upon him, and after a course of a quarter of a mile, they were at his haunches, Killbuck leading. The next instant he sprang in full fly, and got his hold by the ear. So sudden was the shock, that the buck turned a complete somersault, but, recovering himself immediately, he regained his feet, and started off at a gallop down hill towards a stream, the dog still hanging on. In turning over in his fall, the ear had twisted round, and Killbuck, never having left his hold, was therefore on his back, in which position he was dragged at great speed over the rugged ground. Notwithstanding the difficulty of his position, he would not give up his hold. In the meantime, Bran kept seizing the other ear, but continually lost his hold as the ear gave way. Killbuck's weight kept the buck's head on a level with his knees; and after a run of some hundred yards, during the whole of which, the dog had been dragged upon his back without once losing his hold, the elk's pace was reduced to a walk. With both greyhounds now hanging on his ears, the buck reached the river, and he and the dogs rolled down the steep bank into the deep water. I came up just at this moment and killed the elk, but both dogs were frightfully wounded, and for some time I despaired of their recovery.

This was an extraordinary feat in seizing; but Killbuck was matchless in this respect, and accordingly of great value, as he was sure to retain his hold when he once got it. This is an invaluable qualification in a dog, especially with boars, as any uncertainty in the dog's hold, renders the advance of the man doubly dangerous. I have frequently seen hogs free themselves from a dog's hold at the very moment that I have put the knife into them; this with a large boar is likely to cause an accident.

I once saw a Veddah who nearly lost his life by one of these animals. He was hunting 'guanas' (a species of large lizard which is eaten by all the natives) with several small dogs, and they suddenly found a large boar, who immediately stood to bay. The Veddah advanced to the attack with his bow and arrows; but he had no sooner wounded the beast than he was suddenly charged with great fury. In an instant the boar was into him, and the next moment the Veddah was lying on the ground with his bowels out. Fortunately a companion was with him, who replaced his entrails and bandaged him up. I saw the man some years after; he was perfectly well, but he had a frightful swelling in the front of the belly, traversed by a wide blue scar of about eight inches in length.

A boar is at all times a desperate antagonist, where the hunting-knife and dogs are the only available weapons. The largest that I ever killed, weighed four hundredweight. I was out hunting, accompanied by my youngest brother. We had walked through several jungles without success, but on entering a thick jungle in the Elk Plains we immediately noticed the fresh ploughings of an immense boar. In a few minutes we heard the pack at bay without a run, and shortly after a slow running bay-there was no mistake as to our game. He disdained to run, and, after walking before the pack for about three minutes, he stood to a determined bay. The jungle was frightfully thick, and we hastily tore our way through the tangled underwood towards the spot. We had two staunch dogs by our side, Lucifer and Lena, and when within twenty paces of the bay, we gave them a halloa on. Away they dashed to the invisible place of conflict, and we almost immediately heard the fierce grunting and roaring of the boar. We knew that they had him, and scrambled through the jungle as fast as we could towards the field of battle. There was a fight! the underwood was levelled, and the boar rushed to and fro with Smut, Bran, Lena, and Lucifer all upon him. Yoick to him! and some of the most daring of the maddened pack went in. The next instant we were upon him, mingled with a confused mass of hounds, and throwing our whole weight upon the boar, we gave him repeated thrusts, apparently to little purpose. Round came his head and gleaming tusks to the attack of his fresh enemies, but old Smut held him by the nose, and, although the bright tusks were immediately buried in his throat, the staunch old dog kept his hold. Away went the boar covered by a mass of dogs, and bearing the greater part of our weight in addition, as we hung on to the hunting-knives buried in his shoulders. For about fifty paces he tore through the thick jungle, crashing it like a cobweb. At length he again halted; the dogs, the boar, and ourselves were mingled in a heap of confusion. All covered with blood and dirt; our own cheers added to the wild bay of the infuriated hounds and the savage roaring of the boar. Still he fought and gashed the dogs right and left. He stood about thirty-eight inches high, and the largest dogs seemed like puppies beside him; still not a dog relaxed his hold, and he was covered with wounds. I made a lucky thrust for the nape of his neck. I felt the point of the knife touch the bone; the spine was divided, and he fell dead.