полная версия

полная версияJennie Baxter, Journalist

“Is the Director of Police a friend of yours, Herr Feltz? I don’t mean merely an official friend, but a personal friend?”

“I am under many obligations to him, your Highness, and besides that, like any other citizen of Vienna, I am compelled to obey him when he commands.”

“What I want to learn,” continued the Princess, her anger visibly rising at this unexpected opposition, “is whether you wish the man well or not?”

“I certainly wish him well, your Highness.”

“In that case know that if my friend leaves this shop without seeing the analysis of the material she brought to you, the Director of Police will be dismissed from his office to-morrow. If you doubt my influence with my husband to have that done, just try the experiment of sending us away unsatisfied.”

The old man bowed his white head.

“Your Highness,” he said, “I shall take the responsibility of refusing to obey the orders of the Director of Police. Excuse me for a moment.”

He retired into his den, and presently emerged with a sheet of paper in his hand.

“It must be understood,” he said, addressing Jennie, “that the analysis is but roughly made. I intended to devote the night to a more minute scrutiny.”

“All I want at the present moment,” said Jennie, “is a rough analysis.”

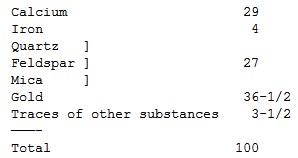

“There it is,” said the chemist, handing her the paper. She read,–

Jennie’s eyes sparkled as she looked at the figures before her. She handed the paper to the Princess saying,—

“You see, I was right in my surmise. More than one-third of that heap is pure gold.”

“I should explain,” said the chemist, “that I have grouped the quartz, feldspar, and mica together, without giving the respective portions of each, because it is evident that the combination represents granite.”

“I understand,” said Jennie; “the walls and the roof are of granite.”

“I would further add,” continued the chemist, “that I have never met gold so finely divided as this is.”

“Have you the gold and other ingredients separated?”

“Yes, madame.”

“I shall take them with me, if you please.”

The chemist shortly after brought her the components, in little glass vials, labelled.

“Have you any idea, Herr Feltz, what explosive would reduce gold to such fine powder as this?”

“I have only a theoretical knowledge of explosives, and I know of nothing that would produce such results as we have here. Perhaps Professor Carl Seigfried could give you some information on that point. The science of detonation has been his life study, and he stands head and shoulders above his fellows in that department.”

“Can you give me his address?”

The chemist wrote the address on a sheet of paper and handed it to the young woman.

“Do you happen to know whether Professor Seigfried or his assistants have been called in during this investigation?”

“What investigation, madame?”

“The investigation of the recent terrible explosion.”

“I have heard of no explosion,” replied the chemist, evidently bewildered.

Then Jennie remembered that, while the particulars of the disaster in the Treasury were known to the world at large outside of Austria, no knowledge of the catastrophe had got abroad in Vienna.

“The Professor,” continued the chemist, noticing Jennie’s hesitation, “is not a very practical man. He is deeply learned, and has made some great discoveries in pure science, but he has done little towards applying his knowledge to any everyday useful purpose. If you meet him, you will find him a dreamer and a theorist. But if you once succeed in interesting him in any matter, he will prosecute it to the very end, quite regardless of the time he spends or the calls of duty elsewhere.”

“Then he is just the man I wish to see,” said Jennie decisively, and with that they took leave of the chemist and once more entered the carriage.

“I want to drive to another place,” said Jennie, “before it gets too late.”

“Good gracious!” cried the Princess, “you surely do not intend to call on Professor Seigfried to-night?”

“No; but I want to drive to the office of the Director of Police.”

“Oh, that won’t take us long,” said the Princess, giving the necessary order. The coachman took them to the night entrance of the central police station by the Hohenstaufengasse, and, leaving the Princess in the carriage, Jennie went in alone to speak with the officer in charge.

“I wish to see the Director of Police,” she said.

“He will not be here until to-morrow morning. He is at home. Is it anything important?”

“Yes. Where is his residence?”

“If you will have the kindness to inform me what your business is, madame, we will have pleasure in attending to it without disturbing Herr Director.”

“I must communicate with the Director in person. The Princess von Steinheimer is in her carriage outside, and I do not wish to keep her waiting.” At mention of the Princess the officer bestirred himself and became tremendously polite.

“I shall call the Director at once, and he will be only too happy to wait upon you.”

“Oh, have you a telephone here? and can I speak with him myself without being overheard?”

“Certainly, madame. If you will step into this room with me, I will call him up and leave you to speak with him.”

This was done, and when the Chief had answered, Jennie introduced herself to him.

“I am Miss Baxter, whom you were kind enough to escort through the Treasury building this afternoon.”

“Oh, yes,” replied the Chief. “I thought we were to postpone further inquiry until to-morrow.”

“Yes, that was the arrangement; but I wanted to say that if my plans are interfered with; if I am kept under surveillance, I shall be compelled to withdraw from the search.”

A few moments elapsed before the Chief replied, and then it was with some hesitation.

“I should be distressed to have you withdraw; but, if you wish to do so, that must be a matter entirely for your own consideration. I have my own duty to perform, and I must carry it out to the best of my poor ability.”

“Quite so. I am obliged to you for speaking so plainly. I rather surmised this afternoon that you looked upon my help in the light of an interference.”

“I should not have used the word interference,” continued the Chief; “but I must confess that I never knew good results to follow amateur efforts, which could not have been obtained much more speedily and effectually by the regular force under my command.”

“Well, the regular force under your command has been at work several weeks and has apparently not accomplished very much. I have devoted part of an afternoon and evening to the matter, so before I withdraw I should like to give you some interesting information which you may impart to the Government, and I am quite willing that you should take all the credit for the discovery, as I have no wish to appear in any way as your competitor. Can you hear me distinctly?”

“Perfectly, madame,” replied the Chief.

“Then, in the first place, inform the Government that there has been no robbery.”

“No robbery? What an absurd statement, if you will excuse me speaking so abruptly! Where is the gold if there was no robbery?”

“I am coming to that. Next inform the Government that their loss will be but trifling. That heap of débris which you propose to cart away contains practically the whole of the missing two hundred million florins. More than one-third of the heap is pure gold. If you want to do a favour to a good friend of yours, and at the same time confer a benefit upon the Government itself, you will advise the Government to secure the services of Herr Feltz, so that the gold may be extracted from the rubbish completely and effectually. I put in a word for Herr Feltz, because I am convinced that he is a most competent man. To-night his action saved you from dismissal to-morrow, therefore you should be grateful to him. And now I have the honour to wish you good-night.”

“Wait—wait a moment!” came in beseeching tones through the telephone. “My dear young lady, pray pardon any fault you have to find with me, and remain for a moment or two longer. Who, then, caused the explosion, and why was it accomplished?”

“That I must leave for you to find out, Herr Director. You see, I am giving you the results of merely a few hours’ inquiry, and you cannot expect me to discover everything in that time. I don’t know how the explosion was caused, neither do I know who the criminals are or were. It would probably take me all day to-morrow to find that out; but as I am leaving the discovery in such competent hands as yours, I must curb my impatience until you send me full particulars. So, once again, good-night, Herr Director.”

“No, no, don’t go yet. I shall come at once to the station, if you will be kind enough to stop there until I arrive.”

“The Princess von Steinheimer is waiting for me in her carriage outside, and I do not wish to delay her any longer.”

“Then let me implore you not to give up your researches.”

“Why? Amateur efforts are so futile, you know, when compared with the labours of the regular force.”

“Oh, my dear young lady, you must pardon an old man for what he said in a thoughtless moment. If you knew how many useless amateurs meddle in our very difficult business you would excuse me. Are you quite convinced of what you have told me, that the gold is in the rubbish heap?”

“Perfectly. I will leave for you at the office here the analysis made by Herr Feltz, and if I can assist you further, it must be on the distinct understanding that you are not to interfere again with whatever I may do. Your conduct in going to Herr Feltz to-night after you had left me, and commanding him not to give me any information, I should hesitate to characterize by its right name. When I have anything further to communicate, I will send for you.”

“Thank you; I shall hold myself always at your command.” This telephonic interview being happily concluded, Jennie hurried to the Princess, stopping on her way to give the paper containing the analysis to the official in charge, and telling him to hand it to the Director when he returned to his desk. This done, she passed out into the night, with the comfortable consciousness that the worries of a busy day had not been without their compensation.

CHAPTER XVI. JENNIE VISITS A MODERN WIZARD IN HIS MAGIC ATTIC

When Jennie entered the carriage in which her friend was waiting, the other cried, “Well, have you seen him?” apparently meaning the Director of Police.

“No, I did not see him, but I talked with him over the telephone. I wish you could have heard our conversation; it was the funniest interview I ever took part in. Two or three times I had to shut off the instrument, fearing the Director would hear me laugh. I am afraid that before this business is ended you will be very sorry I am a guest at your house. I know I shall end by getting myself into an Austrian prison. Just think of it! Here have I been ‘holding up’ the Chief of Police in this Imperial city as if I were a wild western brigand. I have been terrorizing the man, brow-beating him, threatening him, and he the person who has the liberty of all Vienna in his hands; who can have me dragged off to a dungeon-cell any time he likes to give the order.”

“Not from the Palace Steinheimer,” said the Princess, with decision.

“Well, he might hesitate about that; yet, nevertheless, it is too funny to think that a mere newspaper woman, coming into a city which contains only one or two of her friends, should dare to talk to the Chief of Police as I have done to-night, and force him actually to beg that I shall remain in the city and continue to assist him.”

“Tell me what you said,” asked the Princess eagerly; and Jennie related all that had passed between them over the telephone.

“And do you mean to say calmly that you are going to give that man the right to use the astounding information you have acquired, and allow him to accept complacently all the kudos that such a discovery entitles you to?”

“Why, certainly,” replied Jennie. “What good is the kudos to me? All the credit I desire I get in the office of the Daily Bugle in London.”

“But, you silly girl, holding such a secret as you held, you could have made your fortune,” insisted the practical Princess, for the principles which had been instilled into her during a youth spent in Chicago had not been entirely eradicated by residence in Vienna. “If you had gone to the Government and said, ‘How much will you give me if I restore to you the missing gold?’ just imagine what their answer would be.”

“Yes, I suppose there was money in the scheme if it had really been a secret. But you forget that to-morrow morning the Chief of Police would have known as much as he knows to-night. Of course, if I had gone alone to the Treasury vault and kept my discovery to myself, I might, perhaps, have ‘held up’ the Government of Austria-Hungary as successfully as I ‘held up’ the Chief of Police to-night. But with the Director watching everything I did, and going with me to the chemist, there was no possibility of keeping the matter a secret.”

“Well, Jennie, all I can say is that you are a very foolish girl. Here you are, working hard, as you said in one of your letters, merely to make a living, and now, with the greatest nonchalance, you allow a fortune to slip through your fingers. I am simply not going to allow this. I shall tell my husband all that has happened, and he will make the Government treat you honestly; if not generously. I assure you, Jennie, that Lord Donal—no, I won’t mention his name, since you protest so strenuously—but the future young man, whoever he is, will not think the less of you because you come to him with a handsome dowry. But here we are at home; and I won’t say another word on the subject if it annoys you.”

When Jennie reached her delightful apartments—which looked even more luxuriantly comfortable bathed in the soft radiance that now flooded them from quiet-toned shaded lamps than they did in the more garish light of day—she walked up and down her sitting-room in deep meditation. She was in a quandary—whether or not to risk sending a coded telegram to her paper was the question that presented itself to her. If she were sure that no one else would learn the news, she would prefer to wait until she had further particulars of the Treasury catastrophe. A good deal would depend on whether or not the Director of Police took anyone into his confidence that night. If he did not, he would be aware that only he and the girl possessed this important piece of news. If a full account of the discovery appeared in the next morning’s Daily Bugle, then, when that paper arrived in Vienna, or even before, if a synopsis were telegraphed to the Government, as it was morally certain to be, the Director would know at once that she was the correspondent of the newspaper whom he was so anxious to frighten out of Vienna. On the other hand, her friendship with the Princess von Steinheimer gave her such influence with the Chief’s superiors, that, after the lesson she had taught him, he might hesitate to make any move against her. Then, again, the news that to-night belonged to two persons might on the morrow come to the knowledge of all the correspondents in Vienna, and her efforts, so far as the Bugle was concerned, would have been in vain. This consideration decided the girl, and, casting off all sign of hesitation, she sat down at her writing table and began the first chapter of the solution of the Vienna mystery. Her opening sentence was exceedingly diplomatic: “The Chief of Police of Vienna has made a most startling discovery.” Beginning thus, she went on to details of the discovery she had that day made. When her account was finished and codified, she went down to her hostess and said,—

“Princess, I want a trustworthy man, who will take a long telegram to the central telegraph office, pay for it, and come away quickly before anyone can ask him inconvenient questions.”

“Would it not be better to call a Dienstmanner?”

“A Dienstmanner? That is your commissionaire, or telegraph messenger? No, I think not. They are all numbered and can be traced.”

“Oh, I know!” cried the Princess; “I will send our coachman. He will be out of his livery now, and he is a most reliable man; he will not answer inconvenient questions, or any others, even if they are asked.”

To her telegram for publication Jennie had added a private despatch to the editor, stating that it would be rather inconvenient for her if he published the account next morning, but she left the decision entirely with him. Here was the news, and if he thought it worth the risk, he might hold it over; if not, he was to print it regardless of consequences.

As a matter of fact, the editor, with fear and trembling, held the news for a day, so that he might not embarrass his fair representative, but so anxious was he, that he sat up all night until the other papers were out, and he heaved a sigh of relief when, on glancing over them, he found that not one of them contained an inkling of the information locked up in his desk. And so he dropped off to sleep when the day was breaking. Next night he had nearly as much anxiety, for although the Bugle would contain the news, other papers might have it as well, and thus for the second time he waited in his office until the other sheets, wet from the press, were brought to him. Again fortune favoured him, and the triumph belonged to the Bugle alone.

The morning after her interview with the Director of Police, Jennie, taking a small hand-satchel, in which she placed the various bottles containing the different dusts which the chemist had separated, went abroad alone, and hailing a fiacre, gave the driver the address of Professor Carl Seigfried. The carriage of the Princess was always at the disposal of the girl, but on this occasion she did not wish to be embarrassed with so pretentious an equipage. The cab took her into a street lined with tall edifices and left her at the number she had given the driver. The building seemed to be one let out in flats and tenements; she mounted stair after stair, and only at the very top did she see the Professor’s name painted on a door. Here she rapped several times without any attention being paid to her summons, but at last the door was opened partially by a man whom she took, quite accurately, to be the Professor himself. His head was white; and his face deeply wrinkled. He glared at her through his glasses, and said sharply, “Young lady, you have made a mistake; these are the rooms of Professor Carl Seigfried.”

“It is Professor Carl Seigfried that I wish to see,” replied the girl hurriedly, as the old man was preparing to shut the door.

“What do you want with him?”

“I want some information from him about explosives. I have been told that he knows more about explosives than any other man living.”

“Quite right—he does. What then?”

“An explosion has taken place producing the most remarkable results. They say that neither dynamite nor any other known force could have had such an effect on metals and minerals as this power has had.”

“Ah, dynamite is a toy for children!” cried the old man, opening the door a little further and exhibiting an interest which had, up to that moment, been absent from his manner. “Well, where did this explosion take place? Do you wish me to go and see it?”

“Perhaps so, later on. At present I wish to show you some of its effects, but I don’t propose to do this standing here in the passageway.”

“Quite right—quite right,” hastily ejaculated the old scientist, throwing the door wide open. “Of course, I am not accustomed to visits from fashionable young ladies, and I thought at first there had been a mistake; but if you have any real scientific problem, I shall be delighted to give my attention to it. What may appear very extraordinary to the lay mind will doubtless prove fully explainable by scientists. Come in, come in.”

The old man shut the door behind her, and led her along a dark passage, into a large apartment, whose ceiling was the roof of the building. At first sight it seemed in amazing disorder. Huge as it was, it was cluttered with curious shaped machines and instruments. A twisted conglomeration of glass tubing, bent into fantastic tangles, stood on a central table, and had evidently been occupying the Professor’s attention at the time he was interrupted. The place was lined with shelving, where the walls were not occupied by cupboards, and every shelf was burdened with bottles and apparatus of different kinds. Whatever care Professor Seigfried took of his apparatus, he seemed to have little for his furniture. There was hardly a decent chair in the room, except one deep arm-chair, covered with a tiger’s skin, in which the Professor evidently took his ease while meditating or watching the progress of an experiment. This chair he did not offer to the young lady; in fact, he did not offer her a seat at all, but sank down on the tiger’s skin himself, placed the tips of his fingers together, and glared at her through his glittering glasses.

“Now, young woman,” he said abruptly, “what have you brought for me? Don’t begin to chatter, for my time is valuable. Show me what you have brought, and I will tell you all about it; and most likely a very simple thing it is.”

Jennie, interested in so rude a man, smiled, drew up the least decrepit bench she could find, and sat down, in spite of the angry mutterings of her irritated host. Then she opened her satchel, took out the small bottle of gold, and handed it to him without a word. The old man received it somewhat contemptuously, shook it backward and forward without extracting the cork, adjusted his glasses, then suddenly seemed to take a nervous interest in the material presented to him. He rose and went nearer the light. Drawing out the cork with trembling hands, he poured some of the contents into his open palm. The result was startling enough. The old man flung up his hands, letting the vial crash into a thousand pieces on the floor. He staggered forward, shrieking, “Ah, mein Gott—mein Gott!”

Then, to the consternation of Jennie, who had already risen in terror from her chair, the scientist plunged forward on his face. The girl had difficulty in repressing a shriek. She looked round hurriedly for a bell to ring, but apparently there was none. She tried to open the door and cry for help, but in her excitement could neither find handle nor latch. It seemed to be locked, and the key, doubtless, was in the Professor’s pocket. She thought at first that he had dropped dead, but the continued moaning as he lay on the floor convinced her of her error. She bent over him anxiously and cried, “What can I do to help you?”

With a struggle he muttered, “The bottle, the bottle, in the cupboard behind you.”

She hurriedly flung open the doors of the cupboard indicated, and found a bottle of brandy, and a glass, which she partly filled. The old man had with an effort struggled into a sitting posture, and she held the glass of fiery liquid to his pallid lips. He gulped down the brandy, and gasped, “I feel better now. Help me to my chair.”

Assisting him to his feet, she supported him to his arm-chair, when he shook himself free, crying angrily, “Let me alone! Don’t you see I am all right again?”

The girl stood aside, and the Professor dropped into his chair, his nervous hands vibrating on his knees. For a long interval nothing was said by either, and the girl at last seated herself on the bench she had formerly occupied. The next words the old man spoke were, “Who sent you here?”

“No one, I came of my own accord. I wished to meet someone who had a large knowledge of explosives, and Herr Feltz, the chemist, gave me your address.”

“Herr Feltz! Herr Feltz!” he repeated. “So he sent you here?”

“No one sent me here,” insisted the girl. “It is as I tell you. Herr Feltz merely gave me your address.”

“Where did you get that powdered gold?”

“It came from the débris of an explosion.”

“I know, you said that before. Where was the explosion? Who caused it?”

“That I don’t know.”

“Don’t you know where the explosion was?”

“Yes, I know where the explosion was, but I don’t know who caused it.”

“Who sent you here?”

“I tell you no one sent me here.”