полная версия

полная версияPeter and Jane; Or, The Missing Heir

'So one of the men lived to tell tales!' said Peter, leaning forward in his chair; 'and Purvis, who has been here for some time past, is the hero of the story? It is a blackguardly tale, Dunbar, and, thank God, I believe it would have been impossible in England!'

'I don't pass judgment on my fellow-men,' said Dunbar. 'Life is sweet, perhaps, to some of us, and no doubt the whole crew would have swamped the boat, but–'

'But, all the same,' said Toffy, 'you don't mean to let Purvis-Smith get a very light time of it when you do get him.'

'No, I don't,' said Dunbar.

Ross passed out through the door of the little drawing-room to the corridor, and went to see about some work on the farm. The commissario drank his coffee, and Dunbar waited restlessly for his telegram.

After breakfast he and Peter slept for a time, for both were dog-tired, and the day was oppressively hot. In the afternoon a telegram came to say that no news had been heard of Purvis, and that he was believed to be still in the neighbourhood of La Dorada.

'If he is,' said Dunbar, folding up the telegram and putting it into his pocket, 'I think our future duties will not be heavy. The man who has come to light and told the story of the wreck of the Rosana is a native of that favoured spot where already our friend Purvis is not too popular. God help the man if they get hold of him!'

'His little boy is here now,' said Toffy, starting up. 'Purvis came here to leave him in safety.'

Dunbar was writing another telegram to ask the whereabouts of the steamer.

'Then,' he said, 'the story is probably known, and Purvis is aware of it, and has gone north. He daren't show himself near his estancia after this.'

They began to put the story together, piecing it here and there, while Dunbar continued to send telegrams.

Ross strolled in presently to discuss the matter again. 'I don't believe,' he said, 'that Purvis is far off.'

'He is a brave man if he is anywhere near La Dorada,' said Dunbar.

'Purvis is a brave man,' said Ross quietly.

Peter was silent. Only last night he had had good reason to believe that the mystery of his brother's existence was going to be cleared up. But with Purvis gone the whole wearisome business would have to begin again. Why had he not detained the man last night, even if he had had to do it by force, until he had given him all the evidence he possessed? He could not exactly blame himself for not having done so. Purvis had declared that he was only going to Buenos Ayres for a couple of days, and it would have been absurd to delay him that he might give information which perhaps he did not fully possess. Still, the thing had been too cleverly worked out to be altogether a fraud, surely. His thought went back again to the belief that Purvis had got hold of his brother, and had extracted a great deal of information from him, and was only delaying to make him known to Peter until he had arranged the best bargain he could for himself. Looking back on all the talks they had had together there was something which convinced him that Purvis's close application to the search had not been made with a view only of extracting some hundreds of pounds from him, but that the man's game was deeper than that. Purvis was far too clever to waste his talents in dabbling in paltry matters, or in securing a small sum of money for himself. He was a man who worked in big figures, and it was evident that he meant to pull off a good thing.

That his dishonesty was proved was beyond all manner of doubt, and the only thing was to watch events and to see what would now happen. If Purvis gave them the slip what was to be done in the future?

'I believe he will try to save his steamer,' said Ross, after a long silence.

Every one was thinking of the same subject, and his abrupt exclamation needed no explanation.

'If he could trust his hands he might,' said the commissario in halting, broken English; 'but I doubt if they or the peons have been paid lately.'

'Besides, on the steamer,' said Toffy, 'he could be easily caught.'

'Yes,' said Dunbar, 'if he knows that we want to catch him, which he doesn't. He is afraid of the people at La Dorada now; but he is probably unaware of the warm welcome that awaits him in Buenos Ayres.'

Dunbar went to the door again to see if there was any sign of his messenger returning from the telegraph office. The sun was flaming to westward, and Hopwood had moved the dinner-table out into the patio, and was setting dinner there.

'He will do the unexpected thing,' said Ross at last. 'If Purvis ever says he is going to sit up late I know that is the one night of the week he will go to bed early.'

They went out into the patio, and Ross swizzled a cocktail, and they fell to eating dinner; but Dunbar was looking at his watch from time to time, and then turning his glance eastward to the track where his messenger might appear. It was an odd thing, and one of which they were all unaware, that even a slight noise made each man raise his head alertly for a moment as though he might expect an attack.

The sun went down, and still no messenger appeared. They sat down to play bridge in the little drawing-room, and pretended to be interested in the fall of the cards.

'That must be my telegram now,' said Dunbar, starting to his feet as a horse's hoofs were plainly heard in the stillness of the solitary camp. 'Well, I 'm damned,' he said. He held the flimsy paper close to his near-sighted eyes, and read the message to the other men sitting at the table:

'Smith, or Purvis, at present on board his own steamer in midstream opposite La Dorada. Fully armed and alone. Crew have left, and peons in revolt. A detachment of police proceeds by train to Taco to-night. Join them there and await instructions.'

'I thought he would stick to the steamer,' said Ross at last.

'And probably,' said Dunbar, 'he is as safe there as anywhere he can be. He can't work his boat without a crew, but if he is armed he will be able to defend himself even if he is attacked. I don't know how many boats there were at La Dorada, but I would lay my life that Purvis took the precaution of sending them adrift or wrecking them before he got away.'

'What is to be the next move?' said Peter.

'I suppose we shall have to ride down to Taco to-night,' said Dunbar. 'Yon man,' he finished, in his nonchalant voice, 'has given me a good bit of trouble in his time.'

'It seems to me,' said Ross, 'that you can't touch any business connected with Purvis without handling a pretty unsavoury thing.'

'Now, I 'll tell you an odd thing,' said Dunbar. 'I have had to make some pretty close inquiries about Purvis since I have been on his track, and you will probably not believe it if I tell you that by birth he is a gentleman.'

'He behaves like one,' said Ross shortly.

'If I had time,' said Dunbar, 'I could tell you the story, but I see the fresh horses coming round, and I and the commissario must get away to Taco.' He was in the saddle as he spoke, and rode off with the commissario.

'A boy,' said Hopwood, entering presently, 'rode over with this, this moment, sir.' He handed a note to Peter on a little tray, and waited in the detached manner of the well-trained servant while Peter opened the letter.

The writing was almost unintelligible, being written in pencil on a scrap of paper, and it had got crushed in the pocket of the man who brought it.

'It is for Dunbar, I expect,' said Peter, looking doubtfully at the name on the cover. He walked without haste to a table where a lamp stood, and looked more closely at the address. 'No, it's all right, it's for me,' he said.

At first it was the vulgar melodrama of the message which struck him most forcibly with a sense of distaste and disgust, and then he flicked the piece of paper impatiently and said, 'I don't believe a word of it!' His face was white, however, as he turned to the servant and said, 'Who brought this?'

'I will go and see, sir,' said Hopwood, and left the room.

Peter, with the scrap of paper in his hand, walked over to the bridge-table where the others were sitting, and laid the crumpled note in front of them. 'Another trick of our friend Purvis,' he said shortly.

The three men at the card-table bent their heads over the crumpled piece of note-paper spread out before them. Ross smoothed out its edges with his big hand, and the words became distinct enough; the very brevity of the message was touched with sensationalism. It ran: 'I am your brother. Save me!' and there was not another vestige of writing on the paper.

'Purvis has excelled himself,' said Ross quietly. 'It's your deal, Christopherson.'

Toffy mechanically shuffled the cards and looked up into his friend's face. 'Is there anything else?' he said, and Peter took up the dirty envelope and examined it more closely.

There was a scrap of folded paper in one corner, and on it was written in his mother's handwriting a note to her husband, enclosing the photograph of her eldest son in a white frock and tartan ribbons.

Peter flushed hotly as he read the letter. 'He has no business to bring my mother's name into it,' he said savagely; and then the full force of the thing smote him as he realised that perhaps his mother was the mother of this man Purvis too.

'Have a drink?' said Ross, with a pretence of gruffness. It was oppressively hot, and Peter had been riding all the previous night. Ross mentioned these facts in a kindly voice to account for his loss of colour. 'It's a ridiculous try on,' he said, with conviction; and then, seeking about for an excuse to leave the two friends together to discuss the matter, he gathered up the cards from the table, added the score in an elaborate manner, and announced his intention of going to bed.

Dunbar and the commissario had put a long distance between themselves and the estancia house now. The silence of the hot night settled down with its palpable mysterious weight upon the earth. The stars looked farther away than usual in the fathomless vault of heaven, and the world slumbered with a feeling of restlessness under the burden of the aching solitude of the night. Some insects chirped outside the illuminated window-pane, as though they would fain have left the large and solitary splendour without and sought company in the humble room. Time passed noiselessly, undisturbed even by the ticking of a clock. To have stirred in a chair would have seemed to break some tangible spell. A dog would have been better company than a man at the moment, because less influenced by the mysterious night and the silence, and the intensity of thought which fixed itself relentlessly in some particular cells of the brain until they became fevered and ached horribly. A little puff of cooler air began to blow over the baked and withered camp; but the room where the lamp was burning had become intolerably hot, and the mosquitoes which had been contemplating the wall thoughtfully throughout the day began to buzz about and to sing in the ears of the two persons who sat there.

'Damn these mosquitoes!' said Peter, and his voice broke the silence of the lonely house oddly. He and Toffy had not spoken since Ross had left the room, and had not stirred from their chairs; but now the feeling of tension seemed to be broken. Toffy began to fidget with some things on a little table, and opened without thinking a carved cedar-wood work-box which had remained undisturbed until then. He found inside it a little knitted silk sock only half-finished, and with the knitting needles still in it, and he closed the lid of the box again softly.

Peter walked into the corridor and looked out at the silver night. There was a mist rising down by the river, and the feeling of coolness in the air increased. He leaned against the wooden framework of the wire-netting and laid his head on his hands for a moment; then he came back to the drawing-room. 'Do you believe it?' he said suddenly and sharply.

'I suppose it's true,' said Toffy. 'God help us, Peter, this is a queer world!'

'If it were any one else but Purvis!' said Peter with a groan. He had begun to walk restlessly up and down, making his tramp as long as possible by extending it into the corridor. 'And then there is this to be said, Toffy,' he added, beginning to speak at the point to which his thoughts had taken him—'there is this to be said: suppose one could get Purvis out of this hole, Dunbar is waiting for him at Taco. He will be tried for the affair of the Rosana and other things besides, and if he is not hanged he will spend the next few years of his life in prison. It is an intolerable business,' he said, 'and I am not going to move in the matter. One can stand most things, but not being mixed up in a murder case.'

He walked out into the corridor and sat down heavily in one of the deck-chairs there. There was a tumult of thought surging through his mind, and sometimes one thing was uppermost, sometimes another.

If it were possible to get down the river in a boat to the steamer, he thought, there would of course be a chance of bringing Purvis back before it was light; but if he did that he would have to start within the hour. The nights were short.

And then, again, he would be compounding a felony, though in the case of brothers such a law was generally put aside, whatever the results might be.

There was very little chance of an escape. Every one's hand was against Purvis now, and there was the vaguest possibility that he could get away to England. The heir to Bowshott would be doing his time in prison, and that, after all, was the right place for him—or he might be hanged.

And then he, Peter, was the next heir. That was the crux of the whole thing—he, Peter Ogilvie, was the next heir. If anything were to happen to his brother he would inherit everything.

But that, again, was an absurdity. A man in prison, for instance, would not be the inheritor of anything. No, his brother must take his chance down there on the steamer. He had been in tight places before now, and no one knew better how to get out of them. He had some money at his command. Let things take their chance. Yet if Purvis did not inherit, he, Peter, was the next heir.

That was the thought that knocked at him to the exclusion of nearly everything else: he would benefit by his brother's death. Bowshott would be his, and the place in the Highlands, and Jane and he could be married.

He paused for a moment in his feverish survey of events. To think of Jane was to have before one's mind a picture of something absolutely fair and straightforward. A high standard of honour was not difficult to her; it came as naturally as speaking in a well-bred manner, or walking with that air of grace and distinction which was characteristic of her. Such women do not need to preach, and seldom do so. Their lives suggest a torch held high above the common mirk of life. Peter had never imagined for a moment that he was in the least degree good enough for her; but, all the same, he meant to fight for all that he was worth for every single good thing that he could get for her.

… His brother even had a son. His nephew was in the house now. Peter laughed out loud. The boy had a Spanish mother; but if there ever had been a marriage between Purvis and her it could easily be set aside. Purvis had been married several times, or not at all. Dunbar thought that his real wife was an English woman at Rosario.

He reflected with a sense of disgust that, he and Purvis being both of them fair men, it might even be said that they resembled each other in appearance; and he wondered if he would ever hold up his head again now that he knew that the same blood ran in the veins of both, and that this murderer, with his bloodstained hands, was his brother.

And what in Heaven's name was the use of rescuing a man from one difficulty when he would fall into something much worse at the next opportunity?

Finally, there was nothing for it but to remain inactive and let Purvis escape if he could, but to do nothing to help him. Time was getting on now; another half-hour and it would be too late to start.

Perhaps the whole real difficulty resolved itself round Jane. Jane, as a matter of fact, had taken up her position quite close to Peter Ogilvie this evening in the dark of the tropical night. There were probably devils on either side of him, but Jane was certainly there. She looked perfectly beautiful, and there was not a line in her face which did not suggest something fair and honest and of good worth.

… But suppose the man turned out to be an impostor after all? Then Dunbar had better treat with him. The chain of evidence was pretty strong, but there might be a break in it.

… He could not go alone down the river; Ross and Toffy and Hopwood would have to come too, to man the four-oared boat, and some one would have to steer, because the river was dangerous of navigation and full of sandbanks and holes. Why should he involve his friends in such an expedition to save a man who had sneaked off from a boat and left a whole crew to perish, and who had shot in cold blood the men who rowed him to safety?

Before God he was not going to touch the man, nor have anything to do with him!

Half an hour had passed. In twenty minutes it would be too late to start.

Jane drew a little nearer, and just then Toffy laid down the book which he had been reading and strolled about the room. Perhaps he wanted to show Peter that he was still there and awake, and in some way to comfort him by his presence, for he sat down by Mrs. Chance's piano and picked out a tune with one of his fingers.

The devil beside Peter became more imperative and drew up closer, and told him that it was his own sense of honour that made him loathe his reputed brother and turn from him in disgust. He said that the note that had reached him was all part of Purvis's horrible sensationalism and his lies, and that no earthly notice should be taken of it; also, that it would be sheer madness to risk his own life and his friends' for this contemptible fellow. Jane, on the other side—possibly an angel, but to the ordinary mind merely a very handsome English girl—stood there saying nothing, but looking beautiful.

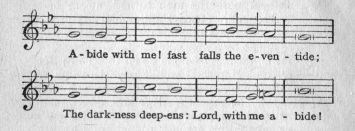

Toffy continued to pick out the tune with his forefinger from Mrs. Chance's book:

It all came before him in a flash: the village church, and the swinging oil-lamps above the pews; he and Jane together in Miss Abingdon's pew, and Mrs. Wrottesley playing the old hymn-tunes on the little organ. He could not remember ever attending very particularly to the evening service. He used to follow it in a very small Prayer Book, and it was quite sufficient for him that Jane was with him. He had never been a religious man in the ordinary sense of the word. He had wished with all his heart when his mother died that he had known more about sacred things, but they had never seemed a necessary part of his life. He knew the code of an English gentleman, and that code was a high one. The youngsters in the regiment knew quite well that he was 'as straight as they make 'em'; but he had never inflicted advice nor had a moment's serious conversation with one of them.

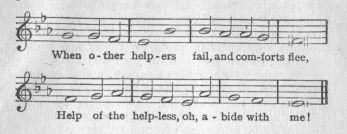

Another ten minutes had passed, and left only five minutes to spare; but Jane was smiling a little, and Toffy was fingering out quavering notes on the old piano:

Life seemed to get bigger as he listened. There were no such things as difficulties. You had just to know what you ought to do, and then to try to do it. You had not to pit yourself against a mean mind, and act meanly by it. Each man had his own work to do, and what other men did or left undone was their own business. His brother was in a mess, and he had to help him out of it, whether he deserved it or no—not weighing his merit, but pardoning his offences and just helping him in his need. The glories of life might fade away, as the old hymn said, or they might last; but all that each man had to care about so long as he remained here was to do justly, and love mercy, and walk humbly with his God.

The angel and the devil—if they existed at all—fled away and left one solitary man standing alone fighting for the sake of honour and clean hands.

The clock struck ten, and the time was up.

Peter went inside and laid his hand on Toffy's shoulder. 'Let's start,' he said, 'if you are ready.'

'All right,' said Toffy, shutting the piano. 'I 'll go and get Ross.'

They were in the boat now, slipping down the stream in the dark. The current in the river was strong here, and the boat slid rapidly between the banks. There was hardly any necessity for rowing. Christopherson sat in the stern with the tiller-ropes in his hands, and Peter reserved his strength for the moment when they should get to the broader part of the river where the stream did not race as it raced here. On their way back they would, of course, avoid the upper reaches of the river, and would land lower down when they had the man well away from his own place. Peter rowed stroke, and Hopwood and Ross rowed numbers one and two. The steering probably was the most difficult part of the business, especially in the present state of the river, and any moment they might go aground or get into some eddy which might turn the bow of the boat and land them in the bank. Rowing was still easy, and Peter was husbanding every ounce of his strength for the pull home. None of the men spoke as the boat slipped down between the banks of dry mud on either side of the river. Some reeds whispered by the shore, and a startled bird woke now and then and flew screaming away. The moon shone fitfully sometimes, but for the most part the night was dark, and the darkness increased towards midnight. Once or twice the breeze carried the intoxicating smell of flowers from the river-bank. It was difficult for Toffy, although he had been down the river many times, to know exactly his bearings. They passed a little settlement on their starboard hand, and saw a few lights burning in the houses.

'That must be Lara's house,' said Peter. 'We will land here on our way back, and get some horses, and ride over to the estancia in the morning.'

The settlement was the last place on the river where Purvis's steamer plied, and there was a small jetty piled with wheat waiting to be taken away. Here the river was broader and much shallower, with stakes of wood set in its bed to show the passage which the little steamer should take.

'We should not be far from La Dorada now,' said Toffy, steering between the lines of stakes; 'but I can't see any signs of the steamer in this blackness.'

In the daytime the river was a pale mud-colour and very thick and dirty-looking. The moon came out for a moment and showed it like a silver ribbon between the grey banks.

'Easy all!' said Toffy, sniffing the air. 'We must be near the canning-factory at La Dorada.'

The horrible smell of the slaughter-house was borne to them on the river, and there were some big corrals close by the water, and a small wharf.

'It reminds me,' thought Toffy, 'of the beastly beef-tea which I have had to drink all my life.'

'Good heavens!' cried Ross, 'they are firing the wharf! Purvis's chances are small if this is their game.'

There was not very much to burn; the wood of the wharf kindled easily, and the wheat burned sullenly and sent up grey volumes of smoke.

'Steer under the bank,' said Peter. 'We don't want to be seen.'

Toffy steered the boat as near the shore as the mud would allow, and as the wood of the wharf burned more brightly he could see some men running to and fro confusedly every few minutes, and then making off farther down the river.

'They 'll fire the steamer next!' said Peter, and then bent his back to the oar, and the boat swung away into the middle of the stream again.

The darkness seemed to increase in depth, as it does just before the dawn: it was baffling in its intensity, and seemed to press close.

'Way enough!' sang out Toffy, for quite unexpectedly the little steamer, tied to a stake in midstream, loomed up suddenly before them. The men shipped their oars with precision, and Toffy caught hold one of the fender-ropes.

'Are you there?' he called up to the deck from the impenetrable darkness.

As he spoke Purvis appeared at the top of the little gangway, dressed in his clerkly suit and stiff hat.