полная версия

полная версияThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction. Volume 12, No. 333, September 27, 1828

Various

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction / Volume 12, No. 333, September 27, 1828

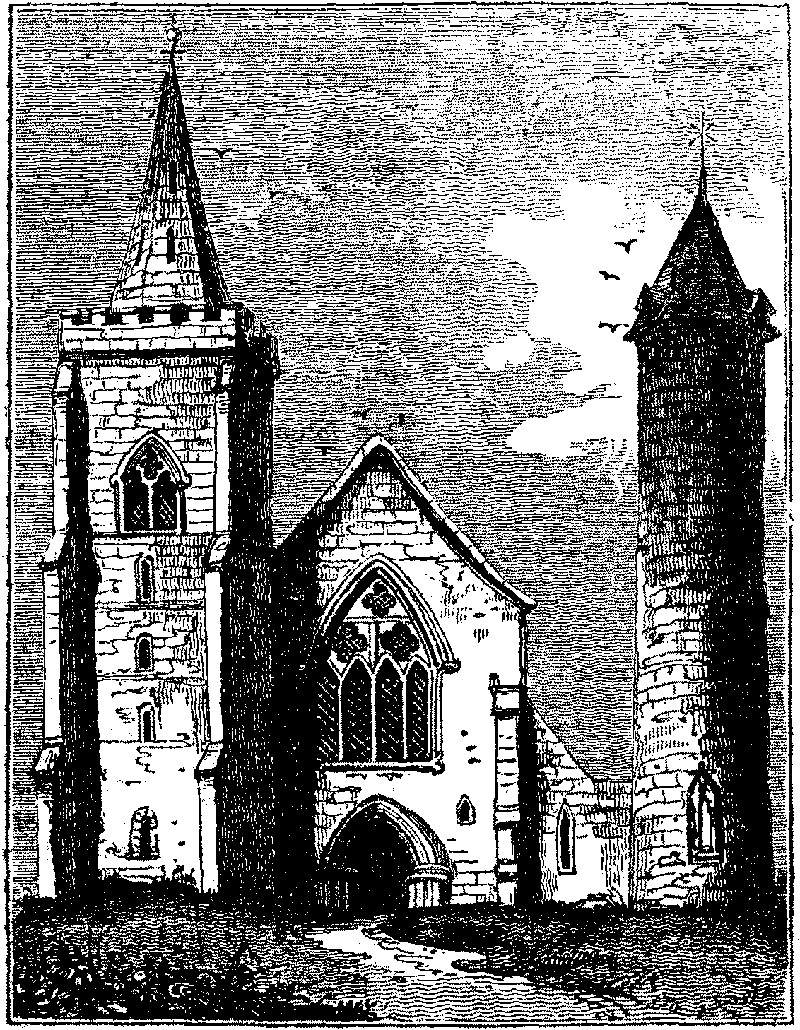

FIRE TOWER

Throughout Scotland and Ireland there are scattered great numbers of round towers, which have puzzled all antiquarians. They have of late obtained the general name of Fire Towers, and our engraving represents the view of one of them, at Brechin, in Scotland. It consists of sixty regular courses of hewn stone, of a brighter colour than the adjoining church. It is 85 feet high to the cornice, whence rises a low, spiral-pointed roof of stone, with three or four windows, and on the top a vane, making 15 feet more, in all 100 feet from the ground, and measuring 48 feet in external circumference.

Many of these towers in Ireland vary from 35 to 100 feet. One at Ardmore has fasciæ at the several stories, which all the rest both in Ireland and Scotland, seem to want, as well as stairs, having only abutments, whereon to rest timbers and ladders. Some have windows regularly disposed, others only at the top. Their situation with respect to the churches also varies. Some in Ireland stand 25 to 125 feet from the west end of the church. The tower at Brechin is included in the S.W. angle of the ancient cathedral, to which it communicates by a door.

There have been numerous discussions respecting the purposes for which these towers were built; they are generally adjoining to churches, whence they seem to be of a religious nature. Mr. Vallencey considers it as a settled point, that they were an appendage to the Druidical religion, and were, in fact, towers for the preservation of the sacred fire1 of the Druids or Magi. To this Mr. Gough, in his description of Brechin Tower,2 raises an insuperable objection. But they are certainly not belfries; and as no more probable conjecture has been made on their original purpose, they are still known as Fire Towers.

For this curious relic we are indebted to Mr. Godfrey Higgins's erudite quarto, entitled "The Celtic Druids," already alluded to at page 121 of our present volume.

SOME ACCOUNT OF STIRBITCH FAIR

BY A SEPTUAGENARIAN

(For the Mirror.)(Stirbitch Fair, as our correspondent observes, was once the Leipsic or Frankfurt of England. He has appended to his "Account" a ground plan of the fair, which we regret we have not room to insert; the gaps or spaces in which, serve to show how much this commercial carnival (for such it might be termed) has deteriorated; for the remaining booths were built on the same site as during the former splendour of the fair. Our correspondent accounts for this "decay, by the facilities of roads and navigable canals for the conveyance of goods;" the shopkeepers, &c, "being able to get from London and the manufacturing districts, every article direct, at a small expense, the fair-keepers find no market for their goods, as heretofore." His paper is, however, a curious matter-of-fact description of Stirbitch, "sixty years since." We have been compelled to reject all but one verse of the "Chaunt," on account of some local allusions, the justice of which we do not deny, but which are scarcely delicate enough for our pages.

Stirbitch is still a festival of considerable extent, although it has lost so much of its commercial importance. There are but few fortnight fairs left: Portsmouth, we recollect, lasts 14 days, and there is a fair held on some fine downs in Dorsetshire, which extends to that period.)

Stirbitch Fair is held in a large field near Barnwell, about two miles from Cambridge, covering a space of ground upwards of two miles in circumference. It commences on the 16th day of September, and continues till the beginning of October, for the sale of all kinds of manufactured and other goods, and likewise for horses.

The etymology of the name of this fair has been much disputed. A silly tradition has been handed down, of a pedlar who travelled from the north to this fair, where, being very weary, he fell asleep at the only inn in the place. A person coming into the room where he lay, the pedlar's dog growled and woke his master, who called out, "Stir, bitch"; when the dog seized the man by the throat, which proved to be the master of the inn, who, to get released from the gripe of the dog, confessed his intention was, with the aid of the ferryman who rowed him over from Chesterton, to rob the pedlar; from which circumstance the fair ever after obtained the name of Stirbitch. But a more reasonable derivation might be found in the known custom of holding a festival on the anniversary of the dedication of any religious foundation. There is a small and very ancient chapel, or oratory, of Saxon architecture, still standing in the field where the fair is kept; but to what saint dedicated, is not recorded. I know not if a St. Ower is to be found in the calendar; if there is, it will, by adding "wijk," or "wych," a district or boundary, be no great stretch of invention to account for a transition from "St. Ower wijch" to Stirbitch; or perhaps from a rivulet which empties itself into the Cam at Quy-water, small streams, in some counties, being called "stours."

Leaving this argument, however, at the road-side chapel, we must proceed to the fair, where the "busy hum of men" announced the approach of the mayor and corporate body to make proclamation. First are,

Mr. Samuel Saul, the beadle, and hisassistant, in full costume, with theirstaves tipped with silver, bearingthe arms of the CorporationNext followed two trumpeters, in gowns,on horsebackSackbut and clarionetsThe maceThe Worshipful the Mayor, in a scarlet gownThe Vicar of Barnwell, (formerly theAbbot,) and other of the Clergyand CollegiansThe Corporate Body, two and twoThe Deputy BeadleAll the train, as above, on horseback,robed in full costumeThen followed Gentlemen and Ladies intheir carriages and on horseback,invited by the Mayor to the granddinner given on the occasionThe proclamation was read, (heads uncovered,) first at the upper end of the fair, next in the Mead where the pottery and coal fair were held, and last at a little inn near the horse fair, in which place a "Pied-poudre" court was held during the fair, for deciding disputes between buyers and sellers, and for punishing abuses and breaches of the peace in a summary way—stocks and a whipping-post being placed before the door for that purpose. Here the mayor and the cavalcade partook of some refreshment.

Should the harvest be backward, and the corn not off the ground, the booths, nevertheless, are erected, the farmers being, as they admit, more than indemnified for their losses in that case, by the immense quantity of litter, offal, and soil left on the ground after the standings and booths are cleared away; besides which, they seize on every thing left upon the land after a fixed day. This has sometimes occurred, and the forfeiture of the goods and chattels so seized has been recognised judicially as a fine for the trespass. This local custom, sanctioned by usage from time immemorial, is without appeal.

The booths were from 15 to 20 feet wide by 25 to 30 feet deep; they were set out in two apartments, the one behind, about 10 feet wide, serving for bed-room, dining-room, parlour, and dressing-room, The bedstead was of four posts and a lath bottom, on which was laid a truss of clean, dry straw, serving as a palliasse, with bed and bedding. The front was fitted up with counters and shelves. The stubble was well trodden into the ground; over which were laid sawdust and boards behind and before the counters, to secure the feet from damp. The shutters, of the space allowed for the windows, were fixed with hinges, and when let down, rested upon brackets, serving as showboards for goods. The booths were constructed of new boards, with gutters for carrying the rain off, and covered with stout hair cloth, with which also a covering was made to an arcade in front, about 10 feet wide. Under this the company walked, protected from rain or the heat of the sun.

The proclamation being made, the clamour and din from the trumpets, drums, gongs, and other noisy instruments, began. The road from Cambridge was actually covered with post-chaises, hackney-coaches from London, gigs, and carts, which brought visiters to the fair from Jesus-lane, in Cambridge, at sixpence each. As soon as you passed the village of Barnwell, your attention was attracted by flags streaming from the show-booths, suttling-booths, &c.; whilst your ears were stunned with the "harsh discord" of a thousand Stentorian bawlers, and the clang of jarring instruments of music. The show-booths were the first on entering the fair, being situated on the north side of the high road. Here were three companies of players, viz. the Norwich company, a very large booth; Mrs. Baker's, whose clown, Lewy Owen, was "a fellow of infinite jest and merriment;" and Bailey's. The latter had formerly been a merchant, and was the compiler of a Directory which bore his name, and was a work of some celebrity and great utility. Fronting these were the fruit and gingerbread stands. On the opposite side of the road stood the cheese fair, attended by dealers from all parts, and where many tons' weight changed hands in a few days, some for the London market, by the factors from thence; and such cheeses as were brought from Gloucester, Cheshire, and Wiltshire, and not made elsewhere, were purchased by the dealers and farmers of Norfolk, Suffolk, and Essex. Opposite the cheese fair, on the north side of the road, stood the small chapel, which was then used as a warehouse for wool, hops, seed, and leather3. Here were the wool-staplers, hop-factors, leather-sellers, and seedsmen. The range of booths in the front were for glovers, leather-breeches makers, saddlers, and other dealers in leather. Opposite to this, at the end of the line of show-booths, Garlick-row commenced; the first range being occupied by hardwaremen, silversmiths, jewellers, and fine ironmongery. The next range was the row of mercers and linen-drapers, where a draper from Holborn had a stock of not less than 5,000l. value. The next range of booths was occupied by stuff-merchants, hosiers, lacemen, milliners, and furriers; here one vender has been known to receive from 1,000l. to 1,200l. for Norwich and Yorkshire goods. A lace-dealer from Tavistock-street likewise attended here with a stock of 2,000l. value, together with many other respectable tradesmen, with goods according to the London fashion. Then followed the ladies and gentlemen's shoe-makers, hatters, and perfumers; and next to the inn was an extensive store of oils, colours, and pickles, kept by an oilman from Limehouse, whose returns were seldom less than 2,000l. during the fair; and the father of the writer of this article, who attended the fair during forty years, usually brought away from 1,200l. to 1,500l. for goods sold and paid for on the spot, exclusive of those sold on credit to respectable dealers, farmers, and gentry. On the outside of the inn were temporary stables for baiting the horses belonging to the visiters. The carriages were drawn up in the fields in a line with the stables or standings for the horses.

Next was the oyster fair; the oysters from Lynn, called the Lynn channel, were the size of a horse's hoof, and were opened with a pair of pincers. At the bottom, in the Mead, next the river, was the coal fair; opposite which were the pottery and fine Staffordshire wares. Returning to and opposite the oyster fair was the horse fair, held on the Friday in the week after the proclamation. The show of beautiful animals here was, perhaps, unrivalled by any fair in the empire; the choicest hunters and racers from Yorkshire, muscular and bony draught-horses from Suffolk and every other breeding county, drew together dealers and gentlemen from all quarters, so that many hundreds of valuable animals changed masters in the space of twelve hours. Higher up was Dockrell's coffee-house and tavern, spacious and well stored with excellent accommodations. About 200 yards onward was Ironmonger-row, where the dealers from Sheffield, Birmingham, Wolverhampton, and other parts, kept large stocks of all sorts of iron and tin wares, agricultural implements, and tools of every description. About 20 yards from them, westward, and bordering on the road, were slop-sellers, dealers in haubergs, wagoners' frocks, and other habiliments for ploughmen; and next, the Hatters'-row. Behind Garlick-row, next the show booths, stood the basket fair, where were sold rakes for haymakers, scythe-hafts, and other implements of husbandry, of which one dealer has been known to sell a wagon-load or two.

Having now made the promenade of the fair, let us step into one of the suttling booths. The principal booth was the Robin Hood, behind Garlick-row, which was fitted up with a good sized kitchen, detached from a long room and parlour. Here were tables covered with baize, and settles of common boards covered with matting. The roof covering was of hair cloth, the same as the shops, but not boarded.

When a new-comer or fresh man arrived to keep the fair, he was required to submit to the ceremony of christening, as it was called, which was performed as follows:—On the night following the horse-fair day, which was the principal day of the whole fair, a select party occupied the parlour of the Robin Hood, or some other suttling booth, to which the novice was introduced, as desirous of being admitted a member, and of being initiated. He was then required to choose two of the company as sponsors, and being placed in an arm-chair, his shoes were taken off, and his head uncovered. The officiator, vested in a cantab's gown and cap, with a book in one hand and a bell in the other, with a verger on each side, robed, and holding staves (alias broomsticks) and candles, preceded by the suttler, bearing a bowl of punch, entered the parlour, and demanded "If there was an infidel present?" Being answered, "Yes," he asked, "What did he require?" Answer. "To be initiated." Q. "Where are the oddfathers?" R. "Here we are." He then proceeded as follows:—

(Plain chant.)"Over thy head I ring this bell, [Rings the bell,Because thou art an infidel,And such I know thee by thy smell.CHORUSWith a hoccius proxius mandamus,Let no vengeance light on him,And so call upon him."Supper was then served up, at the moderate charge of one shilling a head, exclusive of beer and liquors. The cloth being cleared, the smokers ranged themselves round the fire, and kept up the meeting with mirth and harmony, till all retired and were lulled to anticipating dreams of the profits of the coming day, to which they woke with the sun, cheerful and unenvious of each other's success. Such was Stirbitch fair some sixty years ago, as witnessed by

Your constant reader,ΣηνυαNOTES ON NORTHERN LITERATURE

(For the Mirror.)Tordenskiold is a name frequently met with in the annals of Denmark. A singular anecdote is connected with one of the bravest individuals who ever bore the name—the renowned Admiral Tordenskiold, of the days of Frederick IV. While he was yet a young and undistinguished naval officer, he chanced to be in the hall of the royal palace at the time that the king, wearied with the flatteries of some courtiers, who were congratulating him on the success of his war with Sweden, exclaimed, "Ay, I know what you will say, but I should like to know the opinion of the Swedes themselves." Tordenskiold slipped unobserved from the royal palace, hurried to his ship, set sail, and was in an hour on the coast of Sweden. The first sight that caught his eye on landing was a bridal procession. Hastily seizing bride, bridegroom, minister, peasants, and all, he hurried them aboard, and returned to Denmark. Two hours had scarcely elapsed from the moment of the king's expressing his wish, when Tordenskiold, stepping from the crowd of courtiers who surrounded his majesty, informed him that he had now an excellent opportunity of gratifying his wishes, as Swedes of every class of society were in waiting. The astonished monarch, who had not yet missed the young captain from the hall, demanded his meaning; and on being informed of the adventure, summoned the captives to his presence. After gratifying his curiosity, he dismissed them with a handsome present, and ordered them to be conveyed back to Sweden. The promptness of young Tordenskiold was not forgotten, and he speedily rose to the high admiralship of Denmark, a post which he filled with more glory than any other of his countrymen, either before or since.

The memoirs of Lewis Holberg, which have lately appeared in English, are remarkably curious and interesting. It is not generally known, that this celebrated writer, the Moliere of Denmark, was educated at Oxford, whither he repaired penniless, to secure a good education.

Holberg, Samsoe, and Oehlenschlager are the three dramatic luminaries of Denmark. The best production of Samsoe is the play of Dyveke, produced a few days after his death. Such was the enthusiasm it excited, that the following epitaph was proposed to be inscribed on his tomb, in the public cemetery of Copenhagen:—

"Here lies Samsoe;He wrote Dyveke and died."The best poet that Sweden has ever produced is Esaias Tegner, the bishop of Wexio, now living. His first production was Axel, a short poem on the adventures of one of those pages of Charles XII. who were sworn to a single life, to be entirely devoted to the fortunes of war. He has struck out great interest by plunging this hero in love, and painting the conflicts between his passion and his reverence for his oath. The words have been translated into Danish, German, and English. The latter translation appeared in Blackwood's Magazine. Although the Danish language is so akin to the Swedish, that translation is the worst of the three. It is said that this poem procured Tegner the bishoprick of Wexio. A singular circumstance is connected with it. A German literary gentleman was so delighted with the version of it in his own language, that he actually studied Swedish for the sole purpose of reading it in the original.

A compliment like this has rarely been paid, as the poem does not contain more than about a thousand lines. Since then, Tegner has written a poem, entitled Frethioff's Sage founded on one of the wild and singular traditions of the North. It has been more popular than even Axel, and the announcement of a third poem from the same hand, said to outdo all former efforts, excites the greatest interest in Stockholm.

Novels have only been introduced within these few years in Denmark. Ingemann is their most successful manufacturer. His last production is entitled Valdemar Seier, or Waldemar the victorious. The Danes have translations of Sir Walter Scott and Cooper.

It is supposed there are not above three persons in Copenhagen who cannot speak German. Oehlenschlager, the best modern author of Denmark, writes equally well in German and Danish.

ANGLO-SVECUSPLEASURES OF SNUFF-TAKING

Let some the joys of Bacchus praise,The vast delights which he conveys, And pride them in their wine;Let others choose the nice morceau,The piquant joys of feasting know, But other gifts are mine.Give me, ye gods, my quantum suff.Of Grimstone's or Gillespie's snuff— These are the sorts I crave;Defend me from the Lundyfoot,'Tis to my nostrils worse than soot, And from the Irish save.Your Prince's Mixture I despise,It clogs the head and dims the eyes— The nose rejects such burden;Sure 'tis the critic's vast delight,So dull and stupidly they write, I call for witness –.Oh! where shall I for courage fly?Or what restorative apply? A pinch be my resource;Perchance the French are not polite,And with my country wish to fight, Then I must grieve perforce;Or, if with doubt the bosom heaves.The heart for Grecian sorrows grieves, And pines to see them fail.Such critics sometimes court the muse,And I perchance the rhymes peruse, Then heaves the breast with pain.To soothe the mind in such an hour,A pinch of snuff has ample power— One pinch—all's well again.A pinch of snuff delights again,And makes me view with great disdain, And soothes my patriot grief.Thus for the list of human woes,The pangs each mortal bosom knows, I find in snuff relief:It makes me feel less sense of sorrow,When modern bards their verses borrow, And soothes my patriot grief.Then let me sing the praise of snuff—Give me, ye gods, I pray, enough— Let others boast their wine;Let some prefer the nice morceauAnd piquant joys of feasting know, The bliss of snuff be mine.ODE ON A COLLEGE FEAST DAY

(For the Mirror.)Hark! hear ye not yon footsteps dreadThat shook the hall with thundering tread? With eager haste, The fellows past. Each intent on direful work.High lifts the mighty blade and points the deadly fork!But hark! the portals sound and pacing forth, With steps, alas! too slow,The college gips of high illustrious worth With all the dishes in long order go; In the midst, a form divine, Appears the fam'd Sir-loin; And soon with plums and glory crown'd, A mighty pudding sheds its sweets around.Heard ye the din of dinner bray? Knife to fork, and fork to knife: Unnumber'd heroes through the glorious strife,Through fish, flesh, pies, and puddings cut their destin'd way.See, beneath the mighty blade, Gor'd with many a ghastly wound,Low the fam'd Sir-loin is laid, And sinks in many a gulph profound. Arise, arise, ye sons of glory, Pies and puddings stand before ye; See, the ghosts of hungry bellies Point at yonder stand of jellies; While such dainties are beside ye. Snatch the goods the gods provide ye: Mighty rulers of this state, Snatch before it be too late,For, swift as thought, the puddings, jellies, pies,Contract their giant bulks, and shrink to pigmy size.From the table now retreating, All around the fire they meet,And, with wine, the sons of eating, Crown, at length, the mighty treat: Triumphant plenty's rosy graces Sparkle in their jolly faces: And mirth and cheerfulness are seen In each countenance serene. Fill high the sparkling glass, And drink the accustom'd toast; Drink deep, ye mighty host, And let the bottle pass.Begin, begin, the jovial strain, Fill, fill, the mystic bowl,And drink, and drink, and drink again, For drinking fires the soulBut soon, too soon, with one accord they reel Each on his seat begins to nod.All conquering Bacchus' power they feel, And pour libations to the jolly god.At length with dinner, and with wine oppressed,Down in their chairs they sink, and give themselves to rest.HUGH DELMORETHE TOPOGRAPHER

VISIT TO MATLOCK BATHS

(For the Mirror.)It was on a fine evening in autumn, when the rays of departing day began to glimmer in the west, and twilight had just spread her dusky gloom. All was silent, save the low rushing of the Derwent stream, purling its way through dense groves, and winding round the stupendous rock of Matlock's Vale. As I paced along, the grave, sombre hue of evening fell full on the rocks, which rose in magnificent grandeur, and seemed to look with contempt on all around them. These beauties, combined with the gray tint of the stone, the cawing of the rooks, which nestle in the crevices and underwood, with now and then the screeching of the night-owl,—were such as would make the most cold and indifferent acknowledge the delight to be enjoyed in the silent walks of nature.

Perhaps among all the varied scenery in the north of England, none is more sublime than that of Matlock; whose romantic range, interspersed with some of the finest touches of art, forms an interesting contrast. The road from the village to the Baths is as diversified as sublime. It is situated in the bosom of a deep vale; here, on one side, rocks or crags, tower above you to the height of two hundred feet; at the base they form, a graceful slant, which is covered with thick, clustering foliage. On the summit, verdure is seen; and sometimes sheep, unconscious of their danger, will stray, and nip the grass from the very edge. Beneath flows the river Derwent, now, in rapid, though solemn state, reminding us of the peaceful stream of life—but only in fictitious calm, luring on to its more ruffled scenes; next, a rushing noise reminds you a cataract is near, which, combined with the rustling of the foliage by the breeze, wakens the mind to gratifying contemplation. The other side is bounded by immense hills, which have a gradual ascent. Along the regular connexion of the road are cottages, whose symmetry adds the charm of artificial embellishment to this luxuriant display of nature. Here you perceive a sumptuous villa; a little farther, a simple cot, where nature has displayed her master-hand: but the most charming group is where three rows of cottages rise in regular succession towards the summit of the hill, their gardens contrasting with the barren appearance of their opposite neighbours. These delightful scenes alternate until your arrival at the Baths.