Полная версия

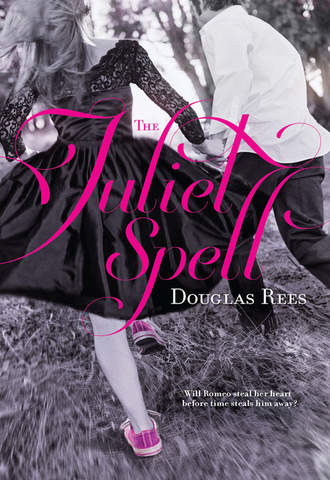

The Juliet Spell

“Aaah?” I said. Or maybe Uuuuuh? Anyway it was something like that.

And with the bright light came a sound like a low bass note that turned into a sort of rumbling thrill, something like an earthquake.

Everyone in California knows what you’re supposed to do when a quake hits. You stand in a doorway. And that’s what I did, even though this was no quake and I knew it. I clutched the door frame with both hands while the white light suddenly filled the whole kitchen, so bright I couldn’t see anything. There was a bang, and the light was gone.

My baking dish was shattered. It lay in two exact halves on the floor. Smoke curled up from each one of them, but there was no crust. They were clean as a pair of very clean whistles.

But that was not the main thing I noticed. No, the main thing I noticed was the tall young man standing on the table in the middle of my glass round. He was about my age, and for some reason he was dressed in tights and boots and a big poofy shirt like he was supposed to be in a play like, say, Romeo and Juliet.

He even looked a little like Shakespeare.

Long hair, a bit of a beard… I screamed.

He smiled, held up one hand, got down on one knee, bowed his head to me and said some words in a language I didn’t understand.

“Speak English,” I said.

The boy looked up, shocked. “Ye’re never Helen of Troy,” the boy said, and leapt to his feet.

“What?” I said.

“These are never the topless towers of Illium,” the boy said, looking around the kitchen wildly.

I screamed again, and he, for some reason, crossed himself, yanked a crucifix out from under his shirt, held it out at me like he thought it was a shield, and shouted, “Doctor D., Doctor D., where are ye?”

Chapter Two

After those frantic moments, we just stared at each other for a bit.

Finally, the boy gulped. I could see his cross was trembling in his hand. He wasn’t the only one trembling.

“What ha’ ye done wi’ Doctor D.?”

“Who the hell are you?” I said.

“Who in hell are ye?” he asked.

“What are you doing here? How did you do that? What do you want?” I shrieked.

I’d cast a spell and it had worked. But it hadn’t worked right. Something was very, very wrong, and I didn’t have a clue what it was, or how to fix it. I was scared, more scared than I’d known I could be.

“Damned spirit, I charge thee, make Doctor D. appear!” the boy shouted. “By the power of the Cross I command thee!”

That made me mad. It was like some guy coming to your door trying to sell you his religion. And being scared already, being mad on top of it made me furious.

“Who the hell are you?” I said again. “What did you just do?”

“I am friend and follower to Doctor D.,” he said. “Who has power over such as ye. Ye know better than I how I come to be here. Release me and return me to him.”

“Get out of here,” I said. “Go back where you came from.”

“Summon Doctor D., or send me back,” the boy said. “I’ll not leave this circle.”

“Shut up and get off the table,” I said, and my voice was so tough even I was scared of it. “Get off right now. It wobbles.”

“Ha, ha. Ye’d like that very well,” the boy sneered. “Ye know well ye cannot hurt me so long as I remain within me circle.”

“It’s my circle,” I said.

“It is?” He looked down, and saw my round tabletop. “Oh, God, I am truly lost. Saint Mary, help me now.”

“If you don’t shut up and get off my table and get out of here, I’m calling 911,” I said, pulling out my cell phone.

He cringed when he saw it.

“No hellish engine shall conjure me from this spot,” he said. “Fetch ye Doctor D. at once, devil thing.” He waved his cross around some more.

I punched in 911.

“All of our lines are busy now,” a so-friendly recording told me. “Please wait and your call will be answered in the order in which it was received.”

“Shit,” I said.

“Doctor D.! Doctor D.!” the boy shouted. “Come ye to me.”

“The cops are coming,” I said, waving my cell phone. “I just said ‘shit’ because I’m excited.”

“Doctor D.!”

Then I had a wild idea. Before Dad went off to develop himself, he used to work out of the house. Maybe this guy was some new kind of crazy, and had come looking for him. This wouldn’t explain little things, like how he got here out of thin air, but like I said, it was a wild idea.

“Are you looking for my dad?” I said. “He’s a doctor, but he’s gone. He left us. But nobody calls him Doctor D.”

“Nay, ye evil wight, I call on Doctor John Dee—John Dee, the greatest man in England. What have ye done with him?”

I held the phone to my ear.

“—your call will be answered—”

A weird cold calm came over me. Whatever was going on, this guy was more frightened of it than I was. I could take control of this situation if I could get control of myself. Treat him like Dad would have: like a patient. Even if he wasn’t crazy, the situation was.

“If you get down off the table and sit down at it and calm down a little, I’ll put the phone away and try to help you,” I said. “Otherwise, you can explain it to the cops when they get here.”

“If ye are not a demon, give me a sign,” the boy said.

“What kind of a sign do you want?”

“Ye must say the Lord’s Prayer.”

“I’m not going to pray,” I said.

“Aha! I knew ye were a servant of the evil one! Help me, Doctor Dee, help me!”

“Oh, all right, damn it. One line. Okay?” I tried to remember Sunday school, but I’d only gone about six times and I hadn’t really liked it. Then I recalled something… “‘Our Father who art in heaven.’ Now get the fuck down.”

The boy looked really confused now. “Ye said the words,” he said. “Ye said the words and did not burst into flames.”

“Yessss… Now get down. And sit down over there.”

“If ye are not a demon, are ye an angel?” the boy asked.

“No,” I said. “Get down.”

“Then are ye a fairy?”

“Not even close. Get down. That table really does have a weak leg. I’m not kidding.”

“Return Doctor Dee and I will,” the boy said.

“I don’t know where he is,” I replied. “You’re the only one here besides me, and you shouldn’t be. But if you’ll start calming down I’ll try to help you.”

“Tell me first what manner of creature ye be. Tell me truly by the power of the Cross.”

“I’m just a girl who doesn’t like people breaking into her house and pitching their religion at her,” I said. “Especially when they erupt out of thin air.”

“A girl? Nay, wench. Ye are like no girl on earth. Ye dress in pants like a Tartary savage, ye’er arms are bare as sticks. Ye’er hair is shorter than mine own. Ye speak strange words in an unknown accent. And ye’ve a—a conjuring thing there in ye’er hand to summon— Copse, ye’er familiar, I doubt not. Tell me what ye truly are.”

“This isn’t getting us anywhere,” I said, trying for calm again. “Why don’t you get down off the table and sit over there in the corner and tell me what you think is going on? ’Cause I don’t have a clue.”

“I’ll not—ye are Queen Mab, or one of her servants.”

Mab, I thought. Queen of the fairies. Mercutio talks about her in Romeo and Juliet. He thinks I’m her?

Then the table collapsed. The boy fell backwards, my little round tabletop flew out from under his feet, and his head hit the wall.

“Ow! Blessed Saint Mary, save me now,” he yelped.

“Damn it, I told you that leg was weak,” I said.

“Don’t turn me into anything,” the boy begged. “I implore you, spirit, or fairy, or whatever thing ye be, have mercy on a poor lost soul.”

I put the cell phone to my ear again.

“—in the order it was received—”

The boy was cowering in the corner now.

“In the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, amen,” he said, crossing himself a couple of times.

Well, at least I had him off the table and into the corner.

“Sit. Stay,” I commanded, like he was a dog, and pointed the phone at him.

He whimpered and drew his knees up to his chest.

One of the things Dad always said about dealing with crazy people was that, before you could help them, you had to find out what reality they were living in.

“Okay,” I said. “I’ll have mercy on you, I promise.”

“Swear you will not turn me into a toad or other loathsome creature,” the boy said.

“I swear not to turn you into anything. Now, my name’s Miranda. What’s yours?”

“Edmund’s me name.”

“Fine,” I said. “Now, where are you from, Edmund? And how did you get here?” My voice was getting calmer. Almost like Dad’s shrink voice. He would have been proud of me.

“London,” he said. “Though as ye can tell from me accent I’m not born there.”

“Actually, I wouldn’t have known that,” I said. “Where are you from originally?”

“Warwickshire, of course.”

“Okay. And who’s this Doctor Dee?”

“As I told ye, Doctor John Dee is the greatest man in England. A mighty mind that knows everything, a valiant heart that dares everything, even the darkest depths of knowledge. Cousin of the queen, friend of all the greats of England. Ye must know of him!”

“Nope. Never heard of him,” I said, kind of amazed he expected me to know some guy half-across the world. “But go on. Tell me what he has to do with you.”

“We were in his secret rooms in Cheapside…. Doctor Dee was casting a spell. A necromancy.” He crossed himself again. “Greatly have we offended. Thus am I punished. Oh, my God, have mercy.”

“Just get back to your story,” I said slowly and calmly. “What’s a necro—what you said?”

“We meant to raise the ghost of Helen of Troy,” he said. “For Doctor Dee, necromancy remains the last great thing undone. He wished to question her about the Iliad. To know how truly it depicted the battles. For me—fool that I am, I wanted to see Helen. To see ‘the face that launched a thousand ships and burned the topless towers of Ilium.’ ’Twas why I addressed ye in Greek at first.”

I was actually calming down a little. And because I was, my legs started shaking really bad. “Edmund, I’m going to sit down now. Don’t be afraid.”

He didn’t say anything.

I sat down beside the broken table. That felt better.

There’s a quick test they give you to find out if you’re crazy or not. If you’re ever taken to the hospital unconscious they’ll give it to you when you wake up. Here it goes.

“Edmund, I’m going to ask you five questions. Real easy ones, okay?”

“What means ‘okay’?”

“Okay? It doesn’t mean anything. I mean, it means a lot of things. It just means okay, okay?”

“I’ll not answer any more questions of yours, save you answer as many questions of mine,” he said.

“Okay,” I said. “In this case, that means ‘yes.’ Okay?”

“Yes. Okay.”

“First question. What’s your name?”

“Edmund Shakeshaft,” he said.

“Almost like the writer.”

“Writer?” he said, as if he didn’t know the word.

“Never mind. You’re Edmund Shakeshaft. Fine. Second question. What country is this?”

“I’ve never a notion,” Edmund said. “What country is this?”

I decided to tell him. “The United States of America.”

“The what of America?”

“Let’s go on,” I said. “You can ask your questions next. Third question. What year is this?”

“1597.”

“Fourth question. What day is this?”

“’Tis the Ides of March,” he said.

“Which is what day of what month?” I said.

“’Tis March the fifteent’, o’course, or a day on either side.”

Maybe it was the Ides of March where he’d been, but here it was the beginning of May.

“One more question,” I said, knowing it would make no sense to him. “Who’s the president of the United States?”

“Who is the what of the what?”

“That’s good, Edmund. We’re done. Now you get five questions.”

Edmund shifted a little. He was getting a bit more comfortable, too.

“First question. Tell me what ye truly are.”

“I already did. I’m a girl named Miranda Hoberman. I’m not a fairy, or a demon, or any of the other things you think I might be. I’m a human being just like you.”

“’Tis easier to believe ye are a fairy…. But ye said a bit of the Lord’s Prayer, which they say no unhallowed wight could do. So I suppose I must believe ye. Well, me next question is, if this be the Americas, what part of them am I in?”

“California,” I said. “It’s part of the United States.”

“Nay, ’tis part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain,” he said. “Nueva España. Doctor Dee has shown me maps. Why d’ye not speak Spanish?”

“I’ll try to explain later,” I said. “Go on.”

“What year is it?”

When I told him, he turned pale. “How can it be? I’m never four hundred years and more in the future.”

“It’s the twenty-first century,” I said.

Edmund was quiet for a long string of minutes. Then he said. “Everyone’s dead. All me friends, all me family. Doctor Dee and everyone. Even the queen must be dead by now, and we thought she’d never die.” He looked so shocked I felt sorry for him. And, I realized right then that I believed him. I had to. Nothing else made any sense.

I held my phone to my ear.

“—order in which—”

I switched it off and stuffed it in my pocket. Being lost in time while Elizabethan wasn’t a crime in California.

“I have just one more question,” Edmund said. “’Tis a boon I would beg of ye. Will ye help me back. Back to me own time?”

“Edmund,” I said. “I’m sorry. I don’t know how this happened. I don’t know if it’s something Doctor Dee did, or something I did, or something that just fell on you out of nowhere. I don’t know how to reverse it. But I will help you all I can. And so will my mother when she gets home. Okay?”

Edmund began to cry.

Chapter Three

Edmund’s shoulders shook. His breath came in terrible gasps. He cried out to God, Saint Mary Mother of God, and Jesus. He called to his mother, his father, to Doctor Dee, and a lot of other names. Then he just wept. I’d never seen a man cry like that. I’d never seen anybody cry like that except my mother when my father left.

I felt so sorry for him. Strange as this whole thing was for me, at least I was still in my own time, with everything I knew about still around me. My mom and I had lost my dad. But Edmund had lost a whole world. And there was no way to get it back. I just sat with my hands in my lap wishing I could think of anything that would help.

Finally, when he had cried himself out, he crossed himself and said, “I am an Englishman. Many of us have been cast on strange strands before this. Come what may, I am still Edmund Shakeshaft. I thank ye, Miranda Hoberman. May God reward your kindness to me.”

“You’re welcome, Edmund,” I said. And then suddenly I had a brilliant idea. “Would you like some tea?”

“Tea?” he said, in a voice that was still shaking.

“Yeah. Mom and I have lots of different kinds.”

“What is tea?” he asked.

“I thought all you English guys drank tea all the time,” I said.

“No,” Edmund said. “Never heard of tea.”

“Well, I’d like some,” I said, hoping it was just a language thing. “Let me make a cup.”

I got up and went over to the stove. I shook the kettle, heard that there was no water in it, and filled it from the tap.

“How does yon work?” he said.

“I don’t really know,” I said. “Water pressure, I guess.”

I went back to the stove and turned on one of the burners.

Edmund stood up to get a better look. Dad would have thought that was a good sign. Getting interested in his surroundings.

“How is’t ye can cook without fire?” he said as the burner began to glow.

“It’s electric,” I said. “Sort of like lightning, but not dangerous. Look.” I walked over to the light switch and flicked it. The light over the table came on.

Edmund stared up at the ceiling. He didn’t look happy.

“Don’t panic,” I quickly said. “It’s not black magic or anything like that. It’s just science. Everybody does this. You can do it.”

“I can?”

I turned off the light. “Come on,” I said. “First lesson in twenty-first-century living.”

He slid along the wall until he was standing beside the light switch.

“Since this is me first time, must I say any special words?” he asked me.

“No. Just push up on the switch.”

He did, and the light, of course, came on. He turned it off. He turned it on. He did it back and forth until the tea-kettle whistled.

“See if you can prop up the table and we’ll sit down,” I said.

While Edmund crawled under the table and tried to stick the leg back on, I got out two mugs and filled them with hot water and tea bags. I figured English breakfast blend was the way to go.

When the tea had steeped, I brought it over to the table. Edmund was sitting at it now, and the thing didn’t shake even when he leaned on it.

“’Tis a simple break at the joint,” he said. “A man could mend it in no time at all.”

“Not my dad… He can fix people, though.”

“A physician, is he?” Edmund asked.

“No. A psychologist. But he’s very good at it,” I said.

“A psychologist. A beautiful word. What does it mean?”

“I guess you’d call him a soul doctor.”

“He must be very holy then,” Edmund said.

“Nope. He’s just good at fixing other people.”

“Mayhap I could mend the table for ye,” he said.

“Mom would like that,” I said. “Try your tea.”

Edmund sipped it.

“Take the bag out first,” I said.

He tried a second sip and made a face. “Strange taste. Have ye no beer?”

“How old are you?” I asked him.

“Sixteen, near seventeen.”

“You have to be twenty-one to drink beer in California,” I said.

“Twenty-one? What the hell for?” he asked. “Are ye savages?”

“Some people start a lot earlier. But it’s illegal if you’re not an adult. And my mom would kill me if I gave one of my friends beer. How about—wait a minute.”

I went to the refrigerator and pulled out a cola. “Try this,” I said, and popped the can open.

Edmund tried one sip. Then he tilted back the can and slurped. “Nectar,” he said. “What d’ye call it?”

“It’s just a cola. Some people call them soft drinks. There’s plenty in there. You can pull one out any time you want.”

Edmund got up and went over to the fridge. “May I open’t?”

“Sure.”

He jumped back when the chill air hit him. “’Tis winter in there!”

“Yep,” I said. “Refrigeration.”

He knelt down and carefully put one hand inside. He felt the food, picked it up and looked at it. Spelled out the words on the packages.

“Is it always so within this chest?” he asked.

“Yeah,” I said. “You can adjust the temperature, but that’s what it’s for. To keep food cold so it doesn’t spoil.”

“’Tis the wonder of the world,” he breathed.

“Wait’ll you see television.”

“Tell-a-vision?” Edmund said. “Prophecy?”

“Not quite,” I said.

“Whatever tell-a-vision be, it must wait—I must ask ye now to lead me to the jakes.”

“The what?”

“The jakes. The necessary. The outhouse. Surely ye have one of those.”

“Let me show you,” I said.

Edmund gulped when he saw the bathroom.

“’Tis like—a sort of temple, so white and set about with basins. It’s never a jakes.”

“Watch me closely,” I said in a voice that I realized probably sounded like a kindergarten teacher’s. “You sit on that. It’s called the toilet. When you’re done you wipe yourself with some of that roll of paper. Then you flush—” I showed him how the handle worked “—and then you wash your hands in the sink. Got it?”

“I’ll do me best,” Edmund said.

“I’ll close the door. But I’ll be right outside. Okay?”

“Ah, okay.”

I waited in the hall. I heard the sounds of flushing and of water running in the sink.

The door opened.

“Must I really wash me hands every single time?” Edmund asked.

“Of course,” I said.

“Feels unnatural.”

“Germs.”

“What?”

“Didn’t Doctor Dee ever tell you anything about germs?” I said.

“Nay, that he did not.”

“My mom will explain all about them. And there’s something else I just thought of.”

“What would that be?” Edmund said.

“We bathe. Every single day. Sometimes more than once.”

“What ever for?”

“Again, germs.”

“But what if I don’t want these germs?” Edmund asked, clearly concerned. “What if I just want to be the way I am?”

“No, Edmund. You don’t get germs from bathing. You’ve got them already. Bathing every day keeps them down. And germs give you diseases.”

“Ye mean like plague?” Edmund asked.

“Yes, exactly like plague,” I said.

“And ye’ve no plague here?”

“Nobody I ever knew or ever heard of has ever had the plague.”

Edmund shook his head. “Ye’ve conquered the plague,” he said. “O, brave new world that hath such people in it.”

“Mom says soap and water can solve half the problems in the world,” I said.

“Very well. I will bathe. Show me what I must do.”

“Wait a minute—I am not going to show you how I bathe,” I exclaimed.

“I never meant for ye to uncover yourself to me. Just show me the equipments.”

“Tub,” I said and pointed. “Taps. Hot water. Cold water. This little gizmo closes the tub. Soap. Shampoo for your hair. Washcloth. Towel for drying off after.”

Edmund was taking everything in like a dry sponge. He pointed over my head and asked, “What is yon?”

“That’s the shower. Some people like showers better than baths.”

“And what does it do? Does it bathe ye, too?”

“Yes. It’s sort of like standing in the rain, only you can make it the temperature you want.”

“I would try it at once,” Edmund said. And he twisted the faucets as far as they would go and plunged his hands under the water.

“Great idea,” I said. “Hand your clothes out through the door and I’ll wash them for you.”

“But they’re the only clothes I’ve got,” he said.

“I’ll find you some others,’ I said. “Trust me, Edmund. Nobody wears codpieces any more.”

“Very good,” he said. “I will fear no evil.”

“Just don’t be afraid of the soap, either.”

I was glad Edmund was being so good about the bath thing. Because he stank. He reeked. It was worse than being with Dad on a three-day camping trip.

I put the smelly tights, shirt, and filthy unmentionables in the wash on gentle, which, since there were no labels with washing instructions, seemed like the safest bet. Then I went back to check on Edmund.

The shower was running full blast, and I could hear him splashing around.

“Everything okay in there?” I shouted.

“Okay, indeed!” he replied. “I’m never coming out.”

“I should tell you, the hot water runs out eventually.”

“Then I’ll come out when it does so,” he said. “This is the greatest work of man since the creation. If only Doctor Dee could know of it.”

I figured this was a good time to find something to cover him up when he was done. I left him splashing away, went into my mom’s bedroom and went through the closet and chest of drawers she’d shared with Dad.

There was quite a bit of his stuff left. He’d been traveling light when he went off to develop as an individual, and I could have dressed Edmund in anything from a three-piece suit (ten years old, but in great shape) to a Moroccan caftan with about a hundred buttons down the front. I decided to go for simple: tan pants, and a polo shirt. I found a belt and some white socks. Nothing would be an exact fit; Dad was taller than Edmund, and Edmund had broader shoulders, but I figured it would get him through till tomorrow. Then Mom and I could get him some stuff.