Полная версия

The Idiot Gods

‘What about the Rite of Spring?’ he said. ‘That sounds like some nice, soft music.’

A few moments later, from another shiny object that seemed all stark planes and hard surfaces like so many human things, a beguiling call filled the air. In its high notes, I heard a deep mystery and the promise of life’s power, almost as if a whale were keening out a long-held desire to love and mate. Soon came crashing chords and complicated rhythms, which felt like a dozen kinds of fish thrashing inside my belly. Various themes, as jagged as a shark’s teeth, tore into one another, interacted for a moment, and then gave birth to new expressions which incorporated the old. Brooding harmonies collided, moved apart, and then invited in a higher order of chaos. Such a brutal beauty! So much blood, exaltation, splendor! The human-made sounds touched the air with a magnificent dissonance and pressed deep into the water in adoration of the earth.

‘What kind of crap is that?’ the golden-haired male said. ‘Turn off that noise before you drive Bobo away again!’

O music! The humans had music: strange, powerful, and complex!

And then, as suddenly as it had begun, the music died.

‘No, no!’ I cried out. ‘More, please – I want to hear more!’

The longer male’s fingers stroked the abalone-like thing for a few moments. He said, ‘What about Beethoven?’

A new music sounded. So very different from the first it was, and yet so alike, for within its simpler melodies and purer beauty dwelled an immense affirmation of life. As the sun moved higher in the sky and the surfer female on the boat stroked my skin, I listened and drank in this lovely music for a long, long time.

Finally, near the end of the composition, a great choir of human voices picked up a heart-opening melody. I listened, stunned. It was almost as if the Old Ones were calling to me.

O the stars! O the sea! They sang of joy!

This realization confirmed all that I had suspected to be true. Although the ability to compose complex music could not be equated with the speaking of language itself, does not all language begin in the impulse of the very ocean to sing?

‘All right, so he likes Beethoven. Let’s try Bach and Brahms.’

As the sun reached its zenith in the blue eggshell of the sky and began its descent into its birth place in the sea, the humans regaled me with other musics. I listened and listened, lost in a sweet, sonic rapture.

‘I think he loves Mozart,’ the shorter male said.

‘I think he loves me,’ the golden-haired surfer said. ‘And I love him.’

To the murmurs of a new melody, the female leaned far out over the boat and pressed her mouth against the skin over my mouth.

‘Bobo, Bobo, Bobo – I wish I could talk to you!’ she said.

‘I wish I could talk to you,’ I told her. I wished I could understand anything of what she or any human said. ‘Can you not even say water?’

I slapped the surface of the sea with my flukes, and carefully enunciated, ‘Water. W-a-t-e-r.’

‘It’s like he wants to talk to me,’ she said.

Having grown frustrated in my desire to touch her with the most fundamental of utterances, I drank in a mouthful of water and sprayed it over her face.

‘Oh, my God! You soaked me! How would you like it if I did that to you?’

Again, I sprayed her and said, ‘Water.’ And then she dipped her hand into the bay, brought it up to her mouth, and sprayed me.

‘So you like playing with water don’t you?’ she said. ‘Well, you’re a whale, so why shouldn’t you? Water, water, everywhere you go.’

Her hand, her hideous but lovely hand that had sent waves of pleasure rippling along my skin, slapped the water much as I had done with my tail. And with each slap, she made a sound with her mouth, which had touched my mouth: ‘Water, water, water.’

The great discoveries in life often come in a moment’s burst like the thunderbolt that flashes out of a long-building storm. I listened as the golden-haired surfer said to me, ‘I wish I could teach you to say water.’ And all the while her clever hand touched the sea in perfect coordination with the sound that poured from her mouth: ‘Water, water, water.’ I realized all at once that she was trying to teach me to speak, in the human way. I realized something else, something astonishing that would open the secret to communicating with these strange animals:

One set of sounds, one word! The humans do not inflect their words according to circumstance, context, or the art of variation! Not even our babies speak so primitively!

‘Water,’ the surfer said again. ‘You understand that, don’t you, Bobo?’

Water, water, water – she kept repeating the simple sequence of taps and tones with an excruciating sameness. I tried to return the favor, trilling out one of the myriad expressions for water in a single way: water.

‘I don’t understand you, though,’ she said to me. ‘I don’t think human beings will ever be able to speak whale.’

The brightness in the surfer’s blue eyes faded, as when a cloud passes over the moon. I feared that she did not understand me.

‘No one can speak to a whale,’ the longer of the males said. ‘They probably don’t even have real language.’

The surfer female looked at me. She thumped her hand against the smooth excrescence upon which she lay and said, ‘Boat.’ And so I learned another word. This game went on until dusk. I collected human words as a magpie gathers up colorful bits of driftglass: Shirt. Fork. Beer. Hair. Ice. Teeth. Lips.

Finally, as the sun sank down into the crimson and pink clouds along the western horizon, the female pressed her hand over her heart and said, ‘Kelly,’ which I supposed must be what the humans call their own kind. The longer of the two male kellies made a similar gesture and said, ‘Zach.’ I laughed then at my stupidity. They were obviously giving me their names.

I gave them mine, but they seemed not to understand what I was doing. Just as the underside of the boat roared into motion, Kelly said to me, ‘Goodbye, Bobo. I love you!’

The next day, and for the remainder of the late summer moon, I had similar encounters with other humans. Strangely, they all seemed to have taken up the game played by Kelly and Zach. I learned many more human words: Lightbulb. Fish. Rifle. Bullet. Knife. Dog. Life preserver. Surfboard. Mouth. Eyes. Penis. I learned many names, too: Jake. Susan. Nika. Keegan. Ayanna. Alex. Jillian. Justine. Most of these humans called me Bobo, and sometimes for fun I returned the misnomer by exercising a willful obtuseness in persisting to think of the humans as male or female kellies.

In the vocalizations of all these many kellies, I began to pick out words that I had mastered. However, the meaning of their communications still largely eluded me. Even so, I memorized all that the kellies said, against the day that I might make sense of what still seemed like gobbledygook:

‘Bobo is back! Hey Lilly, he seems to like talking to you the best. Maybe you can use this for your college essay.’

‘Maybe I can sell the rights to all this, and they can make a movie.’

‘They say Bobo is the smartest orca anyone has ever seen.’

‘I hear he understands everything you say.’

‘Of course he’s trying to communicate with us, and he’s been getting more aggressive, too.’

‘Hey, Bobo, how does it work to mate with a whale?’

‘I’m going to play him some Radiohead. I hear he likes that.’

‘Do you just poop and pee in the water and swim through it?’

‘What do you think Bobo – is there a God?’

‘They’re saying Bobo might hurt someone or injure himself, so they might have to capture him and sell him to Sea Circus.’

‘I love Bobo, and I know he loves me.’

‘If he’s so smart, how come he can’t speak a single word of English?’

How frustrated I was! Not only did I fail to form a single human word, I could not make a single human understand the simplest orca word for water. Upon considering the problem, I realized that much of my success in recognizing the few human words I had been taught lay in the curious power of the human hand. If the humans had not been able to touch or stroke the various objects they presented to me, how would I ever have learned their names?

With this in mind, I broadened my strategy of instructing the humans in the basics of orca speech. I opened my mouth and put tongue to teeth in order to indicate the part of the body that I then named. As well, I licked a human hand and said, ‘Tentacle,’ and with a beat of my flukes I flicked a salmon into one of their boats and said, ‘Fish.’ When that did not avail, I took to nudging various things with my head and calling out sounds that I desperately wished the humans might understand: Driftwood; kelp; sandbar; clam shell. Sadly, the humans still seemed unable to grasp the meaning of what I said – or even that I was trying to teach them.

One gray morning when the sea had calmed and flattened out like the silvery-clear glass that the humans made, I came upon a small boat gliding across the bay. Quiet it was, nearly as quiet as a stealth whale stalking a seal. A lone human male dipped a double-bladed splinter of wood into the water in rhythmic strokes. A violet and green shell of excrescence encased his head. I expected his boat to be made of one of this material’s many manifestations, but when I zanged the boat, I found it was made of skin stretched over a wooden skeleton. I swam in close to make the male’s acquaintance.

‘Hello, brave human, my name is Arjuna.’ I often thought of the humans as brave, for what other land animal who swims so poorly ventures out into the ocean – and alone at that? ‘What are you called?’

This male, however, unlike most humans, remained as quiet as his boat. I came up out of the water, the better to look at him. I liked his black eyes, nearly as large and liquid and full of light as my mother’s eyes. I liked it that he sat within a skin boat. I grew so weary of listening to the echoes of excrescence, which it seemed the humans called plastic.

‘Skin,’ I called out, touching my face to the body of his boat. ‘Your boat is covered with skin, as am I, as are you!’

I did not really think I could teach him this word, any more than I had been able to teach other humans other words. Having been thwarted so many times in my increasingly desperate need to communicate, I pursued accord with this male too strenuously. My pent-up desire to teach one human one orca sound impelled me to nudge the boat as I might one of my own family. It surprised me how insubstantial the boat proved to be. I looked on in dismay as the boat flipped over like a leaf tossed by a wave.

‘Hold your breath!’ I called to the human suspended upside down beneath the boat.

Although I assumed the human must know that he would drown if he breathed water, I could not be sure. I dove beneath the water to help him.

‘Hold onto me!’

I found the male beating his stick through the water. It would have been an easy thing for him to have grasped my fin or tail so that I could pull him around through the gelid sea to return him to the air. Instead, he began beating his stick at me. He thrashed about like a frightened fish. Silver bubbles churned the water. I caught the sound of the human’s heart beating as quickly as a bird’s wings. Through the froth and the fury of the human’s struggle, I gazed at his glorious eyes, grown dark and jumping with a dread of death. Now he did not seem so brave.

‘Wait, wait, wait!’ I told him. ‘I will save you!’

I pressed my head against his side; as gently as I could, I used my much greater substance to move his slight body around and up through the water. This had the effect of turning the boat still attached to him. A moment later, the human breached and choked in a great lungful of air. Water streamed from his face and from the blue plastic skin encasing him. He coughed and sputtered out a spray of spit, for he had sucked water into his blowhole.

After a while, his coughing subsided. His belly, though, tensed up as tight as the skin that covered his little boat. And he called out to me: ‘Goddamned whale! Why can’t you leave us alone?’

Why could I not speak with the humans, I wondered as I swam off in dismay? Through days of clouds and dark nights, I swam back and forth across the bay pondering this problem. I dove deep into the inky waters, believing that if I did so, I might somehow zang how I might talk to the humans – and how, indeed, I might sound the much deeper mystery of how anything spoke with anything at all. What was language, really? For the humans, it seemed nothing more than an arbitrary set of sounds that they attached like so many barnacles to various people, objects, and ideas. From where did these sounds, though, come? What principle or passion ordered them? Could it be, as I very much wanted it to be, that the human language had a deeper structure and intelligence that I could not quite perceive? And that a higher and secret language engendered all the utterances of every individual or every species in the world? And not just of our world, Ocean, but of other worlds such as Agathange, Simoom, and Scutarix? Might there not be, at the very bottom of things, concordant and melodious, a single and universal language through which all beings could communicate?

I felt sure that they must be. One evening, as I lay in deep meditation beneath many fathoms of cold water, it came to me with all the suddenness of a bubble bursting that my approach to speaking with the humans had been all wrong. Before trying to teach them the rudiments of orca speech, which their lips, tongues, and other vocal apparatus might not be able to duplicate, might it not be possible to share with them the impulse beneath language, even as they had shared their musics with me? Yes, I decided, it would be possible. And, yes, yes, I would share with the humans all that I had so far held inside: I would drink in the deepest of breaths and gather up the greatest of inspiration, and I would sing to the humans as no whale had ever sung before!

Some days later, I entered a cove in which floated a large fishing boat. The humans had covered the front of it with gray and white paints in a shape that looked something like the head of a shark. Buoyed as I was by bonhomie and zest for the newfound possibilities of my mission, I paid little attention to the peculiarities of this boat or to the many strands of excrescence that surrounded it like intertangled growths of kelp. Nets, the humans called these fish traps. Today, however, the empty nets had trapped not a single salmon. It seemed that the many noisy humans gesticulating atop the boat had not really come here to fish, but rather to make music for me.

And what music they made! And how they made it! I swam in toward the boat, drawn by the mighty Beethoven chords that somehow sounded from beneath the water. The density of this marvelous blue substance magnified the marvel of the music. Joy, pure joy, zanged straight through my skin. I moved even closer to the boat and to the music’s mysterious source beneath the rippling waves.

‘O what a song I have for you!’ I said to the humans. I knew that if I was to touch their hearts as they had touched mine, I must go deep inside myself to speak with the monsters and the angels that dwelled there. ‘Here, humans, here, here – please listen to this song of myself!’

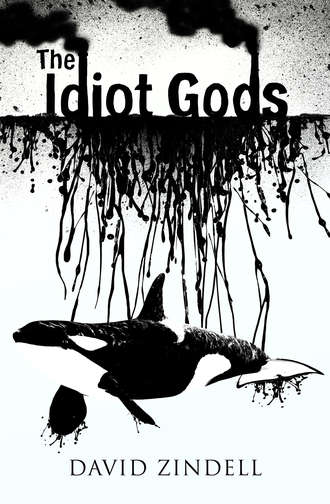

I breached and breathed in a great breath in order to sing. Before the first sound vibrated in my flute, however, the boat began to shudder and shake and to issue sounds of its own. The air sickened with a clanking and grinding. Quicker than I could believe, the nets of excrescence began closing in on me from all sides, like a pack of sharks intent on a feeding frenzy. My heart leaped, not with song but with a fire like that which had burned the waters of the northern sea. I swam to the east, but encountered a web of excrescence in that direction. A dart to the west led straight into yet more netting. I dove, seeking a way beneath the closing nets, but I could not find an escape to the open ocean. In a rage to get away, I swam down through the bitter blue water and then hurled myself in steep arc into the air and over the shrinking sweep of the net. I plunged down with a great splash. For a moment, I thought I was free. It turned out, though, that I had landed within a second layer of netting, which quickly ensnared my tail and fins. The humans – the insightful, intelligent, and treacherous human beings – had considered very carefully how to trap a whale such as I.

As the net tightened around me and pulled me toward the boat and the flensing knives and the teeth that must await me there, I began singing a different song than I had intended: the thunderous and terrible universal song of death that I knew the humans would understand all too well.

5

Water, the fundamental substance, exerts a fundamental force on all things. We of the starlit waves dwell within the ocean, and the ocean surges mighty and eternal within us. We are at one with water – and so we experience the fundamental force as a centering and a calling of like to like that suffuses our bodies with a delightful buoyancy of being. If we are taken out of the water – as the humans pulled me into the air with grinding gears and clanking chains – we continue to feel this force, but in a new and a dreadful way. The centering gives way to separation; the calling becomes a terrible crushing felt in every tissue of skin, nerve, muscle, and bone. It sickens one’s blood with an inescapable heaviness and finds out even the deepest fathoms of the soul.

I had never imagined becoming separated from the sea. To be sure, I had leaped many times into the near-nothingness of air or had played with launching myself up onto an ice floe, as the Others sometimes do when hunting seals. These ventures into alien elements, however, had lasted only moments. I had known that I would return to the water again before my heart beat a few times.

After the humans captured me, I felt no such certainty of deliverance from the crushing force that made breathing such a labor. In truth, the opposite of salvation seemed to be my fate. I could not understand why the humans delayed using their chainsaws to cut me into small pieces that their small mouths could accommodate. Were they not hungry? Would they not soon devour me as they had the many shiny salmon that they trapped in their nets?

The longer that I waited to die, the worse the crushing grew – and the more that I associated this dreadful force with death. I lay on the surface of the ship, and the strands of netting cut into my skin even as the hard, cold iron of the ship thrust up against my chest and belly. I lay within a canvas cocoon as metal bit against metal once more, and the humans lowered me onto a kind of ship that moved over the ground. I lay listening to the growl and grind of more metal vibrating from beneath me and up through my muscles and bones. I lay gasping against the land ship’s poisonous excretions as breathing became a burden and then an agony. I lay within a metal box as a white lightning of a roaring thunder fractured the water within me – and then a sickening sensation took hold of my heaving belly, and I lay within a pool of acid and half-digested fish bits that I had vomited out. I lay within the darkness of the foul, smothering box, and I lay within the much deeper darkness that found its way not just over my eyes and my flesh, but into my mind and my dreams and my blackened and soundless soul.

‘O Mother!’ I cried out. ‘Why did I fail you? Why did you fail me, by bringing me into life?’

I cried out as loud as I could, although it hurt to draw the cloying, slimy air into my lungs.

‘O Grandmother! Why did I not heed your wisdom?’

I cried out again, even though the echoes off the metal close all about me zanged my brain nearly to jelly and deafened me. I cried and cried, but no murmur of help came from without or sounded through the dead ocean within.

For a long time the humans moved me with their various conveyances – I did not know where. The last of these, another land ship, I thought, jumped and stopped, then speeded up with a growl and a belch of smoke, only to stop again, many, many times. I could discern no pattern to its noisy motions. It occurred to me that I should seek relief from all the crushing and the lurching by swimming off into sleep. For the first time in my life, I could sleep with all my brain and mind without breathing water and drowning. I could not sleep, however, even within the tiniest kernel of myself, even for a moment. For if I did sleep, I knew that I would die a different kind of death, becoming so lost within dreams of the family and the freedom I had left behind that I would never want to wake up.

At last, the land ship came to stop longer than any of the other stops. Human voices sounded from outside the metal skin that encased me. Then, from farther away, came other voices, fainter but much more pleasing to my mind: I heard birds squawking and sea lions barking out obnoxious sounds similar to those made by the humans’ dogs. A beluga, too, called out in the sweet dreamy beluga language. A walrus whistled as if to warn me away. Voices of orcas picked up this alarm.

The humans used their cleverness with things to lift me out of the land ship and lower me into a pool of water. How warm it was – too warm, almost as warm as a pool of urine! How it tasted of excrement and chemicals and decaying fish! Even so, it was water, no matter how lifeless or foul, and immediately the crushing force released its hold on my lungs, and I could breathe again. In a way, I was home.

‘Water, water, water!’ I shouted out.

My heart began beating to the wild rhythm of unexpected relief. I felt compelled to swim down nearly to the bottom of the pool and then up to leap high into the air before crashing back down into the water with a huge splash.

‘Yes, that’s right, Bobo!’ A voice hung in the air like a hovering seagull. ‘That’s why we rescued you, why you’re here. Good Bobo, good – very good!’

Humans stood around the edge of the pool. Many of them there were, and each encased in the colorful coverings that they call clothes. These humans, however, unlike those I had known in the bay, covered less of their bodies. I looked up upon bare, brown arms and horribly hairy legs sticking out of half tubes of blue or yellow or red plastic fabric. One of the females was nearly as naked as a whale, with only thin black strips to cover her genital slit and her milk glands.

‘Can you jump again for me?’ she said to me. From a plastic bucket full of dead, dirty fish, she removed a herring and tossed it into the water.

I swam over and nuzzled the herring. Although I was hungry, I did not want to eat this slimy bit of carrion.

‘Here, like this,’ she said.

She clamped her arms against her sides, then jumped up and kicked her feet in a clumsy mockery of a whale’s leap into the air.

‘If he’s as smart as they say he is, Gabi,’ one of the females standing near her said, ‘you’ll have him doing pirouettes in a month.’

‘Wow, look at the size of him!’ a male said. ‘They weren’t lying about how big he is.’

‘Yes, you are big, aren’t you, Bobo?’ the female said. ‘And in a few more months, you’re going to be our biggest star. Welcome to Sea Circus!’

My elation at being once again immersed in water vanished upon a quick exploration of my new environs. How tiny my pool of water was! I could swim across it in little more than a heartbeat. It seemed nearly as tight as a womb, though nothing about it nurtured or comforted. The pool’s walls seemed made of stone covered in blue paint. Whenever I loosed a zang of sonar to keep from colliding with one of the walls, the echoes bounced wildly from wall to wall and filled the pool with a maddening noise. I felt disoriented, abandoned, and lost within a few fathoms of filthy water. I could barely hear myself think.

I did not understand at first why the humans delayed in devouring me. Then, after half a day in the pool, I formed a hypothesis: the few humans I had seen could not possibly eat a whale such as I by themselves. Perhaps they waited for others of their kind to join the feast. Or perhaps they had captured and trapped me for a more sinister reason: here, within a pool so small that I had trouble turning around, they could cut pieces out of me over many days and thus consume me from skin to blubber to muscle to bone. It would take a long time for me to die, and the humans could fill their small mouths and bellies many times. Protected as the pool was by its hard, impenetrable walls, no sharks would arrive to steal me from the humans and finish me off. I would have nearly forever to complete the composition of my death song, which I had begun when trapped by netting in the bay.