Полная версия

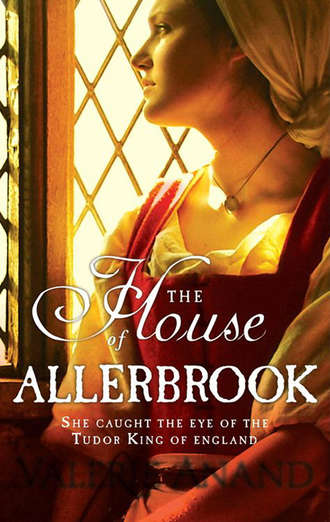

The House Of Allerbrook

Listening to her was no better than looking at her. Had he really ever raved about the beauty of her voice? She was as shrill as a bad-tempered cat. And look at those twisting hands! There was a tiny outgrowth at the base of one little finger, a little extra fingertip, even to the miniature nail. She was ashamed of it and wore long sleeves to conceal it. Once, in their courting days, when he caught sight of it, she had cried and said she hated it, and he had kissed it and called it sweet. Now he thought it an ugly blemish and recoiled from it. Suddenly he lost his temper.

“I have had enough! Half the morning I have been in here with you, listening while you screech at me! All because yesterday afternoon I spoke pleasantly to a shy young girl. She is timid. She was nervous of being alone with her king and I wished to make her mind easy. I will not be accused of…well, what are you accusing me of, if anything?”

“I’m not accusing you!” There was a point past which Anne dared not go. She did not know quite what she feared, except that it was the sense of power that emanated from King Henry. He couldn’t divorce her as he had her predecessor, Catherine of Aragon. He’d never get away with that twice. Catherine was still alive, after all. They’d laugh at him in the streets if he tried to take a third bride while he still had two wives living. Anne knew the people of England had no love for her. She’d heard the names they called her. That witch, Nan Bullen, they said, giving her surname the old English pronunciation rather than the French one, which she preferred. Another name they had for her was The Concubine.

All the same, she couldn’t imagine them letting Henry, their leader under God, play with the sacrament of marriage as though it were a tennis ball. If she couldn’t mend this breach between them, if he wanted to be rid of her and marry again…what would he do?

What, indeed? That was the cause of the fear. It lay deep in her mind, like a dark, frightening well that she didn’t want to look into. The only thing that would release him from her would be her death. And when a man had as much power as Henry had, and such a very great determination to get himself a son, one way or another…

The tears spilled over despite all her efforts to restrain them. She went to the great bed and threw herself down on it, weeping. Henry found himself moved by pity against his will. He went to her and put a hand on her shoulder. Her unblemished hand came up to cover his.

“I want to give you a son,” Anne sobbed. “I want to give you a son, so very, very much.”

Her despair, her defencelessness, stirred him as he had not been stirred for a long time, or not by her. He lifted her, and her thin form felt birdlike. He could have cracked those slender bones in his two hands. He forgot the aversion which had overwhelmed him only a few moments ago. His loins awoke. “Well, there’s only one way to go about that,” he said.

“The one thing none of us must do,” said Sir John Seymour firmly to his daughter, “is offend the king.” He was tired. His sixtieth birthday was behind him and he was feeling his years. “We should have got you married before this, I suppose,” he said. “You are already in your mid-twenties. Only, your mother hoped you would stand a better chance of a really fine match if you were at court. We didn’t expect this.”

“There isn’t really any this,” said Jane Seymour unhappily. “But the queen thinks there is.”

“Let us hope she is wrong, just a jealous woman seeing what isn’t really there. But if it is there…well, my dear, neither I nor your mother would want you to be anything but modest and virtuous. But in the last resort, if the only alternative is to make the king angry—well, don’t. That would be unwise. To annoy the king,” said Sir John warningly, “could be dangerous.”

CHAPTER SIX

Terrifying Ambition 1536

It was the month of May, 1536, and out of doors the world was burgeoning. Now was the time when cows were milked three times a day and on the moor the ponies were dropping their foals. The skies were full of singing skylarks, and in Allerbrook combe the woods echoed with birdsong and the soft call of the wood pigeons. Every part of Jane’s being wanted to be out there, among it all, but these days she rarely had the chance. Life now seemed to be all fine sewing, music and dancing.

She was being relentlessly groomed for court life. The day was coming nearer and nearer when she would be exiled from Allerbrook, perhaps forever. She knew very well that Francis and Eleanor hoped that once at court, she would take the eye of some suitable young man, and marry him. Then she would live wherever his family home might be, even if it was at the other end of England.

It was in her nature to be compliant, and certainly it was in her interests. Both Francis and Eleanor could make themselves unpleasant if crossed. But inside, she was afraid and rebellious and longed to find a way of escape. Except that there didn’t seem to be one.

Master Corby was pleased with her progress on the virginals, except that he said she put a little too much passion into her fingers. The passion came from anger and unhappiness, but it was no use telling him that. At the close of yet another music lesson, she went as she had been bidden to do, to join Eleanor, who was sewing in the parlour above the family chapel, settled in a window seat for the sake of the daylight, her workbox open on a table in front of her.

Eleanor looked a trifle wan and was putting in her stitches in an unusually languid fashion. Jane looked at her pale face and slow movements with some concern and said, “Eleanor, are you well?”

Eleanor, however, glanced up with a smile and said, “I had a restless night, that’s all. I’ve started on a new altar cloth. Come and help. You can embroider at the other end.”

“Where’s Francis today?” Jane asked. “I saw him ride off this morning. From the path he took, I thought he might be going to Dulverton.”

“Yes, he was,” Eleanor said. “To talk to a possible replacement for our poor chaplain. I like to have proper family prayers on weekdays—it keeps a household together in my opinion. I hope Francis brings someone back with him. Listen! The dogs are barking. Is he coming now?”

The window beside Eleanor didn’t overlook the yard. Jane went to one that did, throwing it open in order to look out. “Yes, it is. He’s on his own, though. And Eleanor, the horse is lathered! He never brings a horse in sweating as a rule. Something must have happened! I’ll just run down…”

“No, you won’t. Sit down,” said Eleanor. “No doubt he’ll appear in a moment and tell us all about it. A young lady shouldn’t rush about, asking questions. Come and sew with me.”

Reluctantly Jane seated herself and threaded her needle. Down in the yard, Francis was speaking to someone, probably Tim Snowe. A door slammed, however, as he came indoors and then they heard him call to Peggy, asking where his wife and sister were. A moment later he came racing up the stairs to the parlour. He flung the door open dramatically and stood in the doorway, breathless, so that both of them paused, needles poised, and looked at him in astonishment.

“It’s the queen!” he said.

“The queen?” Eleanor asked. On the stairs behind Francis, Peggy and the maids appeared, eyes wide.

“She’s been arrested,” said Francis. “Dulverton’s buzzing with it. There’s been a King’s Messenger with a proclamation. Queen Anne’s in the Tower of London, charged with treason. For taking lovers. She’s going to be tried. It’s a capital charge. It…it’s…”

“But that’s incredible!” said Eleanor, shocked, her languor quite vanished. “She’s…the queen!”

“The king’s wanted to get rid of her ever since she lost that last pregnancy, the one she must have started last summer, on progress. Ralph Palmer knows all the gossip. He went to London again in February to see his cousin Flaxton and he told me the rumours when he visited us last month. I doubt if anyone will ever know the truth, but I wouldn’t place any heavy bets on her being found innocent,” said Francis. “Even if she is.”

There was a silence. Then Eleanor said, “What about our chaplain?”

“Dr. Amyas Spenlove will join us in a few days. He was chaplain to a man who recently died and made him the executor of his will. He has business to finish before he leaves Dulverton. You’ll like him, I think.”

“We’ll be glad to see him. But this news about the queen,” said Eleanor. “It’s dreadful!”

For the rest of her life Jane was ashamed of the thoughts that went through her head as she sat listening.

If there is no queen of England, then there’ll be no need for ladies-in-waiting or maids of honour. I can stay here.

In the days that followed, news came in successive waves, like a swiftly rising tide.

King Henry, determined now to rid himself forever of the harpy into which his once-adored Anne had turned, wanted his subjects to understand why he was ridding himself of her and how, and wanted them to know, too, that the new marriage he had in mind was lawful. King’s Messengers and town criers were kept busy. Vicars, too, took up the task, repeating the latest announcements from their pulpits. Even the Gypsies who wandered the roads and the charcoal burners who often spent weeks deep in the forests encountered the news before many days had passed.

Yes, the queen was in the Tower. She had been tried, along with her so-called lovers. One of them was her personal musician, whose name was Mark Smeaton. Another was her own brother George. She had been accused of incest as well as adultery. They had all been sentenced to death. The men had been executed but the queen was still alive.

Queen Anne, the last to die, went to the block on Tower Green on May 19. She was executed with a sword, wielded by a professional headsman brought from France for the purpose on Henry’s orders. There was no professional headsman in England accustomed to use the sword, and executions by axe could be very butcherly. Sometimes it took several blows to finish the victim off. The sword, properly handled, was instantaneous.

Cynical people remarked that King Henry evidently wished to be as merciful as he could—as long as he wasn’t left with a living ex-wife whose existence might call the legality of a new marriage into question.

He had enough of that with Queen Catherine, said the knowing voices in the taverns and marketplaces. Well, Catherine of Aragon is dead now, poor soul, and so is Nan Bullen. Never cared for the Bullen witch myself, but I don’t think she got justice.

Nor me. Can’t believe she ever went with her brother, or played the fool with some court minstrel. I mean, I ask you, five of them! If it were just one, well, a fellow might believe it, but five—and her the queen, and adultery for a queen is high treason! She’d have to be out of her mind.

Ah. You’re right there. Whatever next, that’s what we’re all wondering.

Jane heard of the queen’s death from Father Anthony Drew, the vicar of Clicket, on the Sunday following, and shuddered. That Sunday was a particularly lovely May day, more beautiful even than the day when Francis had brought home the news of the queen’s arrest. Rain in the night had been followed at daybreak by drifting early mist and then sudden, lavish sunshine. The tree-hung ride down the combe to Clicket was dappled with it, as though by a scattering of gold coins, and vegetation was growing almost while one watched. Long grass and cow parsley and red valerian overhung the edges of the lanes and the meadowsweet had come out early. May was no month for dying.

Whatever next? Everyone was asking that, and the answer came soon enough. On May 20, the day after Queen Anne’s head had rolled into the straw, King Henry had been betrothed to her former lady-in-waiting Jane Seymour.

On May 30, he married her.

Francis and Jane heard the wedding announced by the Dulverton town crier. Eleanor was not with them. She had of late seemed more and more out of sorts and now they knew why. She had been with child, but something had gone amiss and she had miscarried. She was in bed, with Peggy looking after her, while the new chaplain, Dr. Spenlove, took charge of the house. He was cheerful and competent and had very quickly established himself as someone who could deputize for Francis when required.

“It’s a relief to have him,” Francis said to Jane. “I feel easy about going to Dulverton, and I really must. I’ve half a dozen things to do there. Come with me.” And with that, they set off on the seven-mile ride to the little town, among other things to order supplies of wine from a vintner there, and buy linen to make new shirts for Francis.

On arrival, they heard the loud bell and the stentorian voice of the crier and went toward the sound. They sat on their mounts in the midst of a crowd, listening. When the crier ended his announcement of King Henry’s new marriage, Francis, turning to Jane, said something that terrified her.

“So the new queen’s one of the old one’s ladies-in-waiting. It’s a thousand pities Sybil didn’t behave herself better, or you weren’t a bit older. If one of you had been at court, why, the next queen could have been you!”

He wasn’t joking. Jane knew it at once. He meant what he said. He was harbouring hair-raising ambitions. He was seriously imagining himself as the brother-in-law of King Henry, with one of his sisters on a throne.

“It might be dangerous,” she said, and knew that her voice was trembling. “Look what happened to Queen Anne!”

“Well, I don’t believe it would ever happen to you, though I can’t say the same of Sybil,” Francis said. “Everyone says there was no truth in the charges, but who can really know? Maybe there was.”

“Even with her own brother?” said Jane.

“Yes. I grant you that’s hard to believe,” Francis agreed. “But all the same, I feel that perhaps Queen Anne was…shall we say, not quite trustworthy. What happened to her isn’t likely to happen to anyone else.”

They rode slowly homeward, their various purchases stowed in saddlebags. The moorland tracks were narrow, but when Jane saw a chance to edge her pony up alongside Francis, she seized it.

“Francis, I want to ask you something.”

“Of course. What is it?”

“Please can you tell me how Sybil is? I haven’t seen her or heard a word about her since she went away. The Lanyons haven’t visited us, but I know you’ve seen Master Owen, more than once. I heard you tell Eleanor you’d seen him last year at a fair somewhere….”

“Dunster,” said Francis. “Where the castle is. During the fair, Owen and Katherine dined at Dunster Castle as guests of the Luttrell family. Owen’s a successful man these days.”

“He must have mentioned Sybil, or you must have asked after her, surely! How is she? Did she have the baby safely? I want to know.”

“Sybil is nothing to do with you, Jane. Not anymore.”

“But she is! She’s my sister, whatever she’s done, and if there’s a child, it’s my niece or my nephew. And yours, too!”

Francis relented a little. “Sybil had a boy child last August. He has been named Stephen. They are still with the Lanyons. They are perfectly safe and there’s no need for you to worry about them.”

“I’d like to visit them. I’d like to see Sybil again.”

“No, Jane. I can’t allow that.” Francis spoke sharply. “Your life is going to take a very different course from hers, believe me. With a new queen on the throne, there may well be a need for new maids of honour. I’d like to see you become one of them. I want to bring our family up in the world, Jane. And it’s a hard world. Life was cosier, perhaps, for our forebears. The world is wider now, and colder. You want to stay at Allerbrook, I know, but sometimes, my sister, sacrifices must be made.”

No, prayed Jane, silently but passionately, to God in the sky above, to fate, to Providence—if necessary, to the ancient gods who had been worshipped by the long-departed people who had left their strange marks upon the moor in the form of upright stones and the barrow mounds where they buried their chieftains. There was a barrow on top of the ridge. When she had been free to take walks, she had liked standing on top of it. The view from there was so immense. No, and no and no. I don’t want to go. Don’t make me go. Stop Francis from sending me. Please!

* * *

Her prayers were apparently answered. Word came from London that there were no vacancies for maids of honour or ladies-in-waiting. Queen Jane Seymour had all the ladies and maids that she required.

“Well, the queen’s little namesake is still young,” said Thomas Stone, arriving for the Christmas revel at Allerbrook and greeting Jane with a kiss. “Plenty of time. Maids of honour marry, ladies-in-waiting go home to produce children. Vacancies will arise sooner or later. I fully intend to get Dorothy a place at court one day.”

He and his family had been away on their principal estate in Kent, but had come to Somerset for Christmas so that Mistress Mary Stone could visit her cousins in Porlock, though not stay with them.

“We get on their nerves if we stay long,” Thomas confided, “and there are no girls there of Dorothy’s age. Still, family is family and besides, here in Somerset we can stay at Clicket Hall, which we like very much, and Dorothy can have Jane for company sometimes. Isn’t that so, Dorothy?”

“Yes, of course,” said Dorothy dutifully. Jane tried not to sigh. She did not enjoy spending time with Dorothy Stone, who seemed to her very dull and was inclined to take offence easily. She longed for Sybil instead.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Avenue of Escape 1536–1537

Sybil, at that very moment, was longing with all her heart for Jane.

She had been missing her sister more and more. Jane had been the one person at home who hadn’t condemned her, who had kissed her goodbye and wished her well. Dear, dear Jane. Vaguely, as she rode away with her new guardians, she had hoped that one day, somehow, she and her sister would be together again, but it hadn’t happened. It seemed that her presence in the Lanyon house had changed the relationship between the two families. She knew from overhearing talk between Master Owen and Mistress Katherine that Owen often met Francis, out in the world, frequently at fairs where goods and animals were bought and sold. But it seemed that they had decided to keep their womenfolk apart.

In Lynmouth, Katherine and Owen had duly presented Sybil to their neighbours as a young widow and Stephen had been correctly baptized in the church at Lynmouth. But there had been no celebration to follow. Sybil, it seemed, was to be kept out of the public eye. One of the maidservants told her, spitefully, that Katherine had put it about that she had no dowry because her husband had been poor, and was in any case devoted to his memory and did not intend to remarry.

Sometimes Sybil wished she were really a servant. They were paid and they had time off now and then. She did not.

She was permitted to look after Stephen, but she was encouraged to begin weaning him as soon as possible.

“Children should not be nursed for too long,” Katherine said. “Life is too busy for that.”

Sybil’s constant busyness was Katherine’s fault, but Sybil was afraid to say so.

By the time her second Christmas at Lynmouth arrived, he was nearly seventeen months old, toddling energetically, and making his opinions felt in loud, indignant roars every time he fell down—which was fairly often—or was denied something to which he had taken a fancy, such as a shiny knife or a gold coin carelessly left on a table.

Both Katherine and Owen repeatedly told Sybil to make him behave and she tried, anxiously, but with little success. She had originally hoped that Idwal, who though younger than Sybil was certainly nearer to her in age than his parents were, might be a friend, but he frankly disliked both her and Stephen and if he could get either of them into trouble, he would.

When that second Christmas came, she wondered wistfully if this time there would be some contact with her own family, but there was not, although the weather was good and there was no bar to travelling. The Lanyons stayed in Lynmouth for their Yuletide revels. They let her share in them, but in a limited fashion. It was taken for granted that she would help to wait on the other guests and though Owen, rendered genial by Christmas good cheer, gave her permission to dance, Katherine watched to make sure that no unmarried man danced with her more than once.

The following spring, it was given out one Sunday in church that Queen Jane Seymour was with child, and the congregation were asked to pray for the birth of a healthy prince to be the heir to the kingdom. The Lanyons seemed pleased to hear the news and when they went home, Owen declared that they must have a special dinner to celebrate. “Kate, send someone out to buy a good haunch of something, and we’ll make an occasion of it.”

If Queen Jane did have a boy, Sybil thought, church bells would ring throughout the land. A boy child born to a queen was a marvel, a joy. A boy child born to Sybil Sweetwater might well be stronger, more handsome, cleverer, but he would never be regarded as anything but a mistake and was condemned as a nuisance when he bellowed. That night she cried herself to sleep.

She had done that before, of course, but this time her misery came from a new and greater depth. In the morning she brushed the best of her plain brown gowns, combed her fair hair back, put on a clean coif and went to speak to Master Owen.

Owen Lanyon was preparing for another foreign voyage, and his packed belongings were piled just inside the street door. Idwal was down at the ship, making sure that all was ready. They were to sail to Bristol and then leave for Venice in company with other ships, as a safeguard against pirates. Owen himself was in the small room he used as an office, writing, which he continued to do even after he had answered her timid knock with the call to enter.

Sybil closed the door behind her and stood hesitating, until at length he glanced around and said, “Sit down. I won’t be long. I’m writing to your brother, as it happens.”

“Is there any chance of…of me seeing him? I never have, not since I came here.” Sybil sat down nervously on the nearest stool.

“No, Sybil. There is not.” Owen sanded the letter and blew the sand off. “I’m just giving him some information, in haste, before I set off for Venice. I was in Dunster the other day and I heard some news that may interest your brother. Cleeve Abbey, near Washford, is going to be dissolved after all.”

“Oh,” said Sybil a little blankly.

“Come, now. You know, surely, that the English church has broken free from the Pope and that it has meant retribution at last for the monasteries which for so long have been places of scandal, as well as much too rich.” His sardonic tone suggested that he didn’t entirely sympathize with King Henry’s reforming zeal, or believe that its roots lay in a genuine desire for piety and morality.

Sybil said, “Oh, yes. Father Anthony Drew explained it to us. It was so the king could be free to marry Queen Anne. Only, she didn’t have a son and so…”

“Hush,” said Owen. “His Majesty has for many years been more and more shocked by the mismanagement of the church by Rome, and the sad laxity in the monasteries of England. Any other reason would be unthinkable. Anyway, it’s wiser not to comment on the king’s affairs, even in private, to members of one’s own family. It’s said that he has informers in many houses and who knows which? Never mind that now. The point is that the monks of Cleeve…you know where Cleeve and Washford are?”