Полная версия

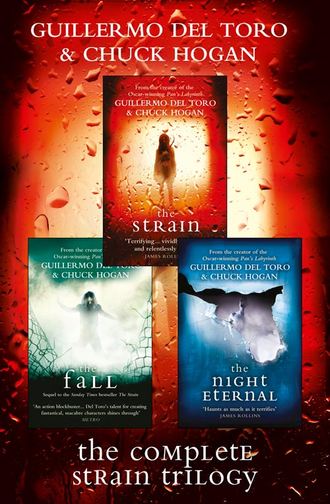

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

Their credentials got them inside, all the way to Dr. Julius Mirnstein, the chief medical examiner for New York. Mirnstein was bald but for tufts of brown hair on the sides and back of his head, long faced, dour by nature, wearing the requisite white doctor’s coat over gray slacks.

“We think we were broken into overnight—we don’t know.” Dr. Mirnstein looked at an overturned computer monitor and pencils spilled from a cup. “We can’t get any of the overnight staff on the phone.” He double-checked that with an assistant who had a telephone to her ear, and who shook her head in confirmation. “Follow me.”

Down in the basement morgue, everything appeared to be in order, from the clean autopsy tables to the countertops, scales, and measuring devices. No vandalism here. Dr. Mirnstein led the way to the walk-in refrigerator and waited for Eph, Nora, and Director Barnes to join him.

The body cooler was empty. The stretchers were all still there, and a few discarded sheets, as well as some articles of clothing. A handful of dead bodies remained along the left wall. All the airplane casualties were gone.

“Where are they?” said Eph.

“That’s just it,” said Dr. Mirnstein. “We don’t know.”

Director Barnes stared at him for a moment. “Are you telling me that you believe someone broke in here overnight and stole forty-odd corpses?”

“Your guess is as good as mine, Dr. Barnes. I was hoping your people could enlighten me.”

“Well,” said Barnes, “they didn’t just walk away.”

Nora said, “What about Brooklyn? Queens?”

Dr. Mirnstein said, “I have not heard from Queens yet. But Brooklyn is reporting the same thing.”

“The same thing?” said Nora. “The airline passengers’ corpses are gone?”

“Precisely,” said Dr. Mirnstein. “I called you here in the hopes that perhaps your agency had claimed these cadavers without our knowledge.”

Barnes looked at Eph and Nora. They shook their heads.

Barnes said, “Christ. I have to get on the phone with the FAA.”

Eph and Nora caught him before he did, away from Dr. Mirnstein. “We need to talk,” said Eph.

The director looked from face to face. “How is Jim Kent?”

“He looks fine. He says he feels fine.”

“Okay,” said Barnes. “What?”

“He has a perforation wound in his neck, through the throat. The same as we found on the Flight 753 victims.”

Barnes scowled. “How can that be?”

Eph briefed him on Redfern’s escape from imaging and the subsequent attack. He pulled an MRI scan from an oversize X-ray envelope and stuck it up on a wall reader, switching on the backlight. “This is the pilot’s ‘before’ picture.”

The major organs were in view, everything looked sound. “Yes?” said Barnes.

Eph said, “This is the ‘after’ picture.” He put up a scan showing Redfern’s torso clouded with shadows.

Barnes put on his half-glasses. “Tumors?”

Eph said, “It’s—uh—hard to explain, but it is new tissue, feeding off organs that were completely healthy just twenty-four hours ago.”

Director Barnes pulled down his glasses and scowled again. “New tissue? What the hell do you mean by that?”

“I mean this.” Eph went to a third scan, showing the interior of Redfern’s neck. The new growth below the tongue was evident.

“What is it?” asked Barnes.

“A stinger,” answered Nora. “Of some sort. Muscular in construction. Retractable, fleshy.”

Barnes looked at her as if she was crazy. “A stinger?”

“Yes, sir,” said Eph, quick to back her up. “We believe it’s responsible for the cut in Jim’s neck.”

Barnes looked back and forth between them. “You’re telling me that one of the survivors of the airplane catastrophe grew a stinger and attacked Jim Kent with it?”

Eph nodded and referred to the scans again as proof. “Everett, we need to quarantine the remaining survivors.”

Barnes checked Nora, who nodded rigorously, with Eph on this all the way.

Director Barnes said, “The inference is that you believe this … this tumorous growth, this biological transformation … is somehow transmissible?”

“That is our supposition and our fear,” said Eph. “Jim may well be infected. We need to determine the progression of this syndrome, whatever it is, if we want to have any chance at all of arresting it and curing him.”

“Are you telling me you saw this … this retractable stinger, as you call it?”

“We both did.”

“And where is Captain Redfern now?”

“At the hospital.”

“His prognosis?”

Eph answered before Nora could. “Uncertain.”

Barnes looked at Eph, now starting to sense that something wasn’t kosher.

Eph said, “All we are requesting is an order to compel the others to receive medical treatment—”

“Quarantining three people means potentially panicking three hundred million others.” Barnes checked their faces again, as though for final confirmation. “Do you think this relates in any way to the disappearance of these bodies?”

“I don’t know,” said Eph. What he almost said was, I don’t want to know.

“Fine,” said Barnes. “I will start the process.”

“Start the process?”

“This will take some doing.”

Eph said, “We need this now. Right now.”

“Ephraim, what you have presented me with here is bizarre and unsettling, but it is apparently isolated. I know you are concerned for the health of a colleague, but securing a federal order of quarantine means that I have to request and receive an executive order from the president, and I don’t carry those around in my wallet. I don’t see any indication of a potential pandemic just yet, and so I must go through normal channels. Until that time, I do not want you harassing these other survivors.”

“Harassing?” said Eph.

“There will be enough panic without our overstepping our obligations. I might point out to you, if the other survivors have indeed become ill, why haven’t we heard from them by now?”

Eph had no answer.

“I will be in touch.”

Barnes went off to make his calls.

Nora looked at Eph. She said, “Don’t.”

“Don’t what?” She could see right through him.

“Don’t go looking up the other survivors. Don’t screw up our chance of saving Jim by pissing off this lawyer woman or scaring off the others.”

Eph was stewing when the outside doors opened. Two EMTs wheeled in an ambulance gurney with a body bag set on top, met by two morgue attendants. The dead wouldn’t wait for this mystery to play itself out. They would just keep coming. Eph foresaw what would happen to New York City in the grip of a true plague. Once the municipal resources were overwhelmed—police, fire, sanitation, morticians—the entire island, within weeks, would degenerate into a stinking pile of compost.

A morgue attendant unzipped the bag halfway—and then emitted an uncharacteristic gasp. He backed away from the table with his gloved hands dripping white, the opalescent fluid oozing from the black rubber bag, down the side of the stretcher, onto the floor.

“What the hell is this?” the attendant asked the EMTs, who stood by the doorway looking particularly disgusted.

“Traffic fatality,” said one, “following a fight. I don’t know … must have been a milk truck or something.”

Eph pulled gloves from the box on the counter and approached the bag, peering inside. “Where’s the head?”

“In there,” said the other EMT. “Somewhere.”

Eph saw that the corpse had been decapitated at the shoulders, the remaining mass of its neck splattered with gobs of white.

“And the guy was naked,” added the EMT. “Quite a night.”

Eph drew the zipper all the way down to the bottom seam. The headless corpse was overweight, male, roughly fifty. Then Eph noticed its feet.

He saw a wire wound around the bare big toe. As though there had been a casualty tag attached.

Nora saw the toe wire also, and blanched.

“A fight, you say?” said Eph.

“That’s what they told us,” said the EMT, opening the door to the outside. “Good day to you, and good luck.”

Eph zipped up the bag. He didn’t want anyone else seeing the tag wire. He didn’t want anyone asking him questions he couldn’t answer.

He turned to Nora. “The old man.”

Nora nodded. “He wanted us to destroy the corpses,” she remembered.

“He knew about the UV light.” Eph stripped off his latex gloves, thinking again of Jim, lying alone in isolation—with who could say what growing inside him. “We have to find out what else he knows.”

17th Precinct Headquarters, East Fifty-first Street, Manhattan

SETRAKIAN COUNTED thirteen other men inside the room-size cage with him, including one troubled soul with fresh scratches on his neck, squatting in the corner and rubbing spit vigorously into his hands.

Setrakian had seen worse than this, of course—much worse. On another continent, in another century, he had been imprisoned as a Romanian Jew in World War II, in the extermination camp known as Treblinka. He was nineteen when the camp was brought down in 1943, still a boy. Had he entered the camp at the age he was now, he would not have lasted a few days—perhaps not even the train ride there.

Setrakian looked at the Mexican youth on the bench next to him, the one he had first seen in booking, who was now roughly the same age Setrakian had been when the war ended. His cheek was an angry blue and dried black blood clogged the slice beneath his eye. But he appeared to be uninfected.

Setrakian was more concerned about the youth’s friend, lying on the bench next to him, curled up on his side, not moving.

For his part, Gus, feeling angry and sore, and jittery now that his adrenaline was gone, grew wary of the old man looking over at him. “Got a problem?”

Others in the tank perked up, drawn by the prospect of a fight between a Mexican gangbanger and an aged Jew.

Setrakian said to him, “I have a very great problem indeed.”

Gus looked at him darkly. “Don’t we all, then.”

Setrakian felt the others turning away, now that there would be no sport to interrupt their tedium. Setrakian took a closer look at the Mexican’s curled-up friend. His arm lay over his face and neck, his knees were pulled up tight, almost into a fetal position.

Gus was looking over at Setrakian, recognizing him now. “I know you.”

Setrakian nodded, used to this, saying, “118th Street.”

“Knickerbocker Loan. Yeah—shit. You beat my brother’s ass one time.”

“He stole?”

“Tried to. A gold chain. He’s a druggie shitbag now, nothing but a ghost. But back then, he was tough. Few years older than me.”

“He should have known better.”

“He did know better. Why he tried it. That gold chain was just a trophy, really. He wanted to defy the street. Everybody warned him, ‘You don’t fuck with the pawnbroker.’”

Setrakian said, “The first week I took over the shop, someone broke my front window. I replaced it—and then I watch, and I wait. Caught the next bunch who came to break it. I gave them something to think about, and something to tell their friends. That was more than thirty years ago. I haven’t had a problem with my glass since.”

Gus looked at the old man’s crumpled fingers, outlined by wool gloves. “Your hands,” he said. “What happened, you get caught stealing once?”

“Not stealing, no,” said the old man, rubbing his hands through the wool. “An old injury. One I did not receive medical attention for until much too late.”

Gus showed him the tattoo on his hand, making a fist so that the webbing between his thumb and forefinger swelled up. It showed three black circles. “Like the design on your shop sign.”

“Three balls is an ancient symbol for a pawnbroker. But yours has a different meaning.”

“Gang sign,” said Gus, sitting back. “Means thief.”

“But you never stole from me.”

“Not that you knew, anyway,” said Gus, smiling.

Setrakian looked at Gus’s pants, the holes burned into the black fabric. “I hear you killed a man.”

Gus’s smile went away.

“You were not wounded? The cut on your face, you received from the police?”

Gus stared at him now, like the old man might be some kind of jailhouse informer. “What’s it to you?”

Setrakian said, “Did you get a look inside his mouth?”

Gus turned to him. The old man was leaning forward, almost in prayer. Gus said, “What do you know about that?”

“I know,” said the old man, without looking up, “that a plague has been loosed upon this city. And soon the world beyond.”

“This wasn’t no plague. This was some crazy psycho with kind of a … a crazy-ass tongue coming up out of his …” Gus felt ridiculous saying this aloud. “So what the fuck was that?”

Setrakian said, “What you fought was a dead man, possessed by a disease.”

Gus remembered the look on the fat man’s face, blank and hungry. His white blood. “What—like a pinche zombie?”

Setrakian said, “Think more along the lines of a man with a black cape. Fangs. Funny accent.” He turned his head so that Gus could hear him better. “Now take away the cape and fangs. The funny accent. Take away anything funny about it.”

Gus hung on the old man’s words. He had to know. His somber voice, his melancholy dread, it was contagious.

“Listen to what I have to say,” the old man continued. “Your friend here. He has been infected. You might say—bitten.”

Gus looked over at unmoving Felix. “No. No, he’s just … the cops, they knocked him out.”

“He is changing. He is in the grip of something beyond your comprehension. A disease that changes human people into non-people. This person is no longer your friend. He is turned.”

Gus remembered seeing the fat man on top of Felix, their maniacal embrace, the man’s mouth going at Felix’s neck. And the look on Felix’s face—a look of terror and awe.

“You feel how hot he is? His metabolism, racing. It takes great energy to change—painful, catastrophic changes are taking place inside his body now. The development of a parasitic organ system to accommodate his new state of being. He is metamorphosing into a feeding organism. Soon, twelve to thirty-six hours from the time of infection, but most likely tonight, he will arise. He will thirst. He will stop at nothing to satisfy his craving.”

Gus stared at the old man as though in a state of suspended animation.

Setrakian said, “Do you love your friend?”

Gus said, “What?”

“By ‘love,’ I mean honor, respect. If you love your friend—you will destroy him before he is completely turned.”

Gus’s eyes darkened. “Destroy him?”

“Kill him. Or else he will turn you.”

Gus shook his head in slow motion. “But … if you say he’s already dead … how can I kill him?”

“There are ways,” said Setrakian. “How did you kill the one who attacked you?”

“A knife. That thing coming out of his mouth—I cut up that shit.”

“His throat?”

Gus nodded. “That too. Then a truck hit him, finished the job.”

“Separating the head from the body is the surest way. Sunlight also works—direct sunlight. And there are other, more ancient methods.”

Gus turned to look at Felix. Lying there, not moving. Barely breathing. “Why doesn’t anybody know about this?” he said. He turned back to Setrakian, wondering which one of them was crazy. “Who are you really, old man?”

“Elizalde! Torrez!”

Gus was so absorbed in the conversation that he never saw the cops enter the cell. He looked up at hearing his and Felix’s names and saw four policemen wearing latex gloves come forward, geared up for a struggle. Gus was pulled to his feet before he even knew what was happening.

They tapped Felix’s shoulder, slapped at his knee. When that failed to rouse him, they lifted him up bodily, locking their arms underneath his. His head hung low and his feet dragged as they hauled him away.

“Listen, please.” Setrakian got to his feet behind them. “This man—he is sick. Dangerously ill. He has a communicable disease.”

“Why we wear these gloves, Pops,” called back one cop. They wrenched up Felix’s limp arms as they dragged him through the door. “We deal with STDs all the time.”

Setrakian said, “He must be segregated, do you hear me? Locked up separately.”

“Don’t worry, Pops. We always offer preferential treatment to killers.”

Gus’s eyes stayed on the old man as the tank door was closed and the cops pulled him away.

Stoneheart Group, Manhattan

HERE WAS the bedroom of the great man.

Climate controlled and fully automated, the presets adjustable through a small console just an arm’s reach away. The shushing of the corner humidifiers in concert with the drone of the ionizer and the whispering air-filtration system was like a mother’s reassuring hush. Every man, thought Eldritch Palmer, should slumber nightly in a womb. And sleep like a baby.

Dusk was still many hours away, and he was impatient. Now that everything was in motion—the strain spreading throughout New York City with the sure exponential force of compound interest, doubling and doubling itself again every night—he hummed with the glee of a greedy banker. No financial success, of which there had been plenty, ever enlivened him as much as did this vast endeavor.

His nightstand telephone toned once, the handset flashing. Any calls to this phone had to be routed through his nurse and assistant, Mr. Fitzwilliam, a man of extraordinary good judgment and discretion. “Good afternoon, sir.”

“Who is it, Mr. Fitzwilliam?”

“Mr. Jim Kent, sir. He says it is urgent. I am putting him through.”

In a moment, Mr. Kent, one of Palmer’s many well-placed Stoneheart Society members, said, “Yes, hello?”

“Go ahead, Mr. Kent.”

“Yes—can you hear me? I have to talk quietly …”

“I can hear you, Mr. Kent. We were cut off last time.”

“Yes. The pilot had escaped. Walked away from testing.”

Palmer smiled. “And he is gone now?”

“No. I wasn’t sure what to do, so I followed him through the hospital until Dr. Goodweather and Dr. Martinez caught up with him. They said Redfern is okay, but I can’t confirm his status. I heard another nurse saying I was alone up here. And that members of the Canary project had taken over a locked room in the basement.”

Palmer darkened. “You are alone up where?”

“In this isolation ward. Just a precaution. Redfern must have hit me or something, he knocked me out.”

Palmer was silent for a moment. “I see.”

“If you would explain to me exactly what I am supposed to be looking for, I could assist you better—”

“You said they have commandeered a room in the hospital?”

“In the basement. It might be the morgue. I will find out more later.”

Palmer said, “How?”

“Once I get out of here. They just need to run some tests on me.”

Palmer reminded himself that Jim Kent was not an epidemiologist himself, but more of a facilitator for the Canary project, with no medical training. “You sound as though you have a sore throat, Mr. Kent.”

“I do. Just a touch of something.”

“Mm-hmm. Good day, Mr. Kent.”

Palmer hung up. Kent’s exposure was merely an aggravation, but the report about the hospital morgue room was troubling. Though in any worthy venture, there are always hurdles to overcome. A lifetime of deal making had taught him that it was the setbacks and pitfalls that make final victory so sweet.

He picked up the handset again and pressed the star button.

“Yes, sir?”

“Mr. Fitzwilliam, we have lost our contact within the Canary project. You will ignore any further calls from his mobile phone.”

“Yes, sir.”

“And we need to dispatch a team to Queens. It seems there may be something in the basement of the Jamaica Hospital Medical Center that needs retrieving.”

Flatbush, Brooklyn

ANN-MARIE BARBOUR checked again to make sure that she had locked all the doors, then went through the house twice—room by room, top to bottom—touching every mirror twice in order to calm herself down. She could not pass any reflective surface without reaching out to it with the first two fingers of her right hand, a nod following each touch, a rhythmic routine resembling genuflection. Then she went through a third time, wiping each surface clean with a fifty-fifty mix of Windex and holy water until she was satisfied.

When she felt in control of herself again, she phoned her sister-in-law, Jeanie, who lived in central New Jersey.

“They’re fine,” said Jeanie, referring to the children, whom she had come and picked up the day before. “Very well behaved. How is Ansel?”

Ann-Marie closed her eyes. Tears leaked out. “I don’t know.”

“Is he better? You gave him the chicken soup I brought?”

Ann-Marie was afraid her trembling lower jaw would be detected in her speech. “I will. I … I’ll call you back.”

She hung up and looked out the back window, at the graves. Two patches of overturned dirt. Thinking of the dogs lying there.

Ansel. What he had done to them.

She scrubbed her hands, then went through the house again, just the downstairs this time. She pulled out the mahogany chest from the buffet in the dining room and opened up the good silver, her wedding silver. Shiny and polished. Her secret stash, hidden there as another woman might hide candy or pills. She touched each utensil, her fingertips going back and forth from the silver to her lips. She felt that she would fall apart if she didn’t touch every single one.

Then she went to the back door. She paused there, exhausted, her hand on the knob, praying for guidance, for strength. She prayed for knowledge, to understand what was happening, and to be shown the right thing to do.

She opened the door and walked down the steps to the shed. The shed from which she had dragged the dogs’ corpses to the corner of the yard, not knowing what else to do. Luckily, there had been an old shovel underneath the front porch, so she didn’t have to go back into the shed. She buried them in shallow soil and wept over their graves. Wept for them and for her children and for herself.

She stepped to the side of the shed, where orange and yellow mums were planted in a box beneath a small, four-pane window. She hesitated before looking inside, shading her eyes from the sunlight. Yard tools hung from pegboard walls inside, other tools stacked on shelves, and a small workbench. The sunlight through the window formed a perfect rectangle on the dirt floor, Ann-Marie’s shadow falling over a metal stake driven into the ground. A chain like the one on the door was attached to the stake, the end of which was obscured by her angle of vision. The floor showed signs of digging.

She went back to the front, stopping before the chained doors. Listening.

“Ansel?”

No more than a whisper on her part. She listened again, and, hearing nothing, put her mouth right up to the half inch of space between the rain-warped doors.

“Ansel?”

A rustling. The vaguely animalistic sound terrified her … and yet reassured her at the same time.

He was still inside. Still with her.

“Ansel … I don’t know what to do … please … tell me what to do … I can’t do this without you. I need you, dearest. Please answer me. What will I do?”

More rustling, like dirt being shaken off. A guttural noise, as from a clogged pipe.

If she could just see him. His reassuring face.

Ann-Marie reached inside the front of her blouse, drawing out the stubby key that hung on a shoelace there. She reached for the lock that secured the chain through the door handles and inserted the key, turning it until it clicked, the curved top disengaging from the thick steel base. She unwound the chain and pulled it through the metal handles, letting it fall to the grass.