Полная версия

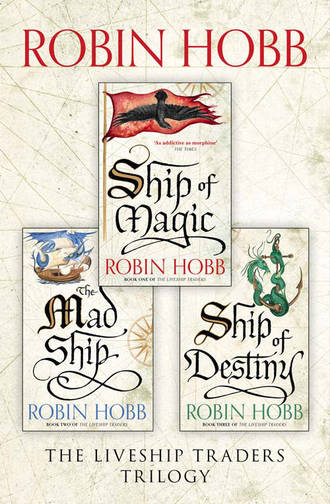

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

As predicted, a fat yellow-green serpent trolled along in the ship’s wake like a contented mascot. If the girth of the serpent was any indication, this slaver had already put a good part of its cargo overboard. Kennit squinted at the slaver’s deck. There were a great deal more people standing about on the deck than he would have expected. Had the slavers taken to carrying a fighting force to protect themselves? He frowned to himself at the idea, but as the Marietta slowly overtook the Sicerna, Kennit realized that the folk huddled together on the deck were slaves. Their worn rags flapped in the brisk winter winds, and while individuals shifted, no one appeared to move freely. The captain had probably brought a batch up on deck to give them a breath of fresh air. Kennit wondered if that meant they had sickness down below. He had never known a slaver to worry solely about his wares’ comfort.

Sorcor was closing up the distance between them now, and the reek of the slave-ship carried plainly on the wind. Kennit took a lavender-scented kerchief from his pocket and held it lightly to his face to mask the effluvium. ‘Sorcor! A word with you,’ he called.

Almost instantaneously, the mate was at his side. ‘Cap’n?’

‘I believe I shall lead the men this time. Pass the word firmly amongst them. I want at least three of the crew left alive. Officers, preferably. I’ve a question or two I’d like answered before we feed the serpents.’

‘I’ll pass the word, sir. But it won’t be easy to hold them back.’

‘I have great confidence they can manage it,’ Kennit observed in a voice that left little doubt as to the hazards of disobedience.

‘Sir,’ Sorcor replied, and went to pass the word to those on deck and to the armed boarders who waited below.

She waited until Sorcor was out of earshot before Etta asked in a low voice, ‘Why do you choose to risk yourself?’

‘Risk?’ He considered it a moment, then asked her, ‘Why do you ask? Do you fear what would happen to yourself if I were killed?’

The lines of her mouth went flat. She turned aside from him. ‘Yes,’ she said softly. ‘But not in the way you think I do.’

They had crept up to hailing distance, when the captain of the Sicerna called to them across the water.

‘Stand off!’ he roared. ‘We know who you be, no matter what flag you show.’

Kennit and Sorcor exchanged a look. Kennit shrugged. ‘The masquerade ends early.’

‘Hands on deck!’ Sorcor bellowed cheerfully. ‘And heave the ropes up.’

The decks of the Marietta resounded to the pounding of eager feet. Pirates crowded the railing, grappling-lines and bows at the ready. Kennit cupped his hands to his mouth. ‘You may surrender,’ he offered the man as the lightened Marietta closed with her prey.

For an answer, the man barked some command of his own. Six stalwart sailors abruptly seized up an anchor lying on the deck. Screams sounded as they hove it over the side. And in its wake, as swiftly as if they had eagerly leaped, went a handful of men who had been manacled to it. They vanished instantly, their screams bubbled into silence. Sorcor stared in shock. Even Kennit had to admit a sort of awe at the other captain’s ruthlessness.

‘That was five slaves!’ bellowed the captain of the Sicerna. ‘Stand off! The next measure of chain has twenty fastened to it.’

‘Probably the sickly ones he didn’t expect to last the journey anyway,’ Kennit opined. From the deck of the other vessel, he could hear voices, some raised in pleas, others in terror or anger.

‘In Sa’s name, what do we do?’ Sorcor breathed. ‘Those poor devils!’

‘We do not stand off,’ Kennit said quietly. Loudly, he called back, ‘Sicerna? If those slaves go over the side, you pay with your own lives.’

The other captain threw back his head and laughed so ringingly that the sound came clear across the water to them. ‘As if you would let any of us live! Stand off, pirate, or these twenty die.’

Kennit looked at the agony in Sorcor’s face. He shrugged. ‘Close the distance! Grapples away!’ he shouted. His men obeyed. They could not see the indecision in the mate’s eyes, but all heard the screams of twenty men as a second anchor dragged them down. They took part of the ship’s railing with them.

‘Kennit,’ Sorcor groaned in disbelief. His face paled with horror and shock.

‘How many spare anchors can he have?’ Kennit asked as he sprang to lead the boarding party. Over his shoulder he flung back, ‘You were the one who told me you would have preferred death to slavery. Let us hope it was their preference as well!’

His men were already hauling on the grappling-lines, drawing the two ships closer, while his archers kept up a steady rain of arrows against the defenders who sought to pluck the grapples out and throw them overboard. The crew of the Marietta outnumbered that of the Sicerna at least three times over. The embattled defenders were well-armed, but obviously unfamiliar with their weapons. Kennit drew his blade and jumped the small gap between the boats. He landed, then gut-kicked a sailor with one arrow standing out of his shoulder as he wrestled with his own bow. The man went down and one of Kennit’s men knifed him in passing. Kennit spun on him. ‘Leave three alive!’ he spat angrily. No one else challenged his boarding, and with drawn sword he went seeking the vessel’s captain.

He found him on the opposite side of the vessel. He, the mate, and two sailors were hastily trying to launch the ship’s boat. It hung swinging over the water from its davits, but one of the release-lines was jammed. Kennit shook his head to himself. The entire ship was filthy; they should not be surprised at a seized-up block if they could not even keep the deck clear.

‘Avast!’ he shouted with a grin.

‘Stand clear,’ the Sicerna’s captain warned him, levelling a hand-held crossbow at his chest.

Kennit lost respect for him. He had been far more impressive when he acted instead of threatening first. And then, arcing up from the water came the sinuous neck of the serpent. Perhaps the man did not wish to expend his bolt until he knew which target was more threatening. As the serpent’s head lifted from the water, Kennit saw the body of a slave gripped in the serpent’s jaws. Twin chains hung from the man’s body. To one side, a manacle still gripped a hand and arm. The other chain dangled slack and empty. The serpent gave a sudden worrying shake to the body, then a slight toss. The great jaws closed more firmly on its catch, shearing away the still-manacled hands at the elbows. The chain splashed back into the water. The serpent threw back its head and gulped the rest of the man down. As the bare feet vanished down its throat, it gave its head another shake. Then it eyed the men in the boat with interest. One of the sailors cried out in horror. The captain aimed his weapon at the monster’s wide eyes.

The moment it was not pointed at his chest, Kennit sprang forwards. He poised his blade to chop one of the davit-lines that supported the boat. ‘Throw down the weapon and come back on board,’ Kennit ordered him. ‘Or I’ll feed you to the serpent now!’

The man spat at Kennit, then fired the bolt unerringly into the serpent’s swirling green eye. The bolt vanished from sight into the creature’s brain. Kennit guessed it was not the first serpent the man had shot. As the creature went into a frenzy of lashing and screaming, the man drew his own knife and began sawing at the line just above the hook that secured it to the boat. ‘We’ll take our chances with the serpents, you bastard!’ he screamed at Kennit as the undulating serpent sank beneath the waves. ‘Rodel, cut your line loose!’

Rodel, however, did not share his skipper’s optimism regarding the serpent. The terrified sailor gave a cry of despair and flung himself from the dangling boat back to the ship’s deck. Kennit disabled him with a cut to his leg and then put his attention back on the boat. He ignored the cries of the squirming sailor who tried vainly to stem the flow of his blood.

With a single stride Kennit sprang into the swinging boat. He set the tip of his blade to the captain’s throat. ‘Back,’ he suggested with a smile. ‘Or die here.’

The seized-up block-and-tackle suddenly broke free. One end of the suspended boat dropped abruptly, spilling men into the sea even as the serpent once more erupted to the surface. Kennit, lithe and lucky as a cat, sprang clear of the falling boat. One hand caught the railing of the Sicerna, and then the other. He was hauling up his dangling legs when the serpent lifted its head from the water to regard him. Its ruined eye ran ichor and blood. It opened its maw wide and screamed, a sound of fury and despair. Its blinded eye faced towards the men who struggled in the water, while Kennit dangled before the good eye like a fishing lure. Frantically he swung one leg up over the railing and hooked it there. As softly as a well-trained pet takes a titbit from its master’s fingers, the serpent closed its jaws on his other leg.

It hurt, it burned like a red-hot leg-iron, and he screamed. Then the pain suddenly flowed away from him. A chill, delightfully numbing, chased the pain away as hot water purges cold from the skin. He felt it flowing up his body. Relief, such relief from the pain. He felt his leg relax with it, and then the numbness was flowing higher. His scream died away to a groan.

‘NO!’ The whore shrieked the word as she flew across the deck. Etta must have been watching from the deck of the Marietta. No one blocked her way. The deck was mainly cleared of live men; they had probably fallen back at sight of the serpent rising again. Some impromptu weapon, a boarding-axe or a kitchen cleaver, flashed in the sunlight as Etta brandished it. She was screaming, a stream of gutter invective and threats directed towards the serpent that even now was lifting him up. Some reflex made him cling to the ship’s railing with all his might. That was not much any more. Strength had fled him. Whatever venom the serpent had put into his wound was already rendering him helpless. When Etta seized him in a wild embrace that also included the ship’s railing, he scarcely felt her grip. ‘Let him go!’ she commanded the serpent. ‘Let him go, you bitch-thing, you slimy sea-worm, you whore’s arse! Let him go!’

The enfeebled serpent tugged on his booted leg, stretching him out over the water. Etta hauled determinedly back. The woman was stronger than he had thought. He saw more than felt the serpent set its teeth more firmly. Like a hot knife through butter, those teeth sheared through flesh and muscle. He had a glimpse of exposed bone, looking oddly honeycombed where the serpent’s saliva ate into it. The creature turned its great head like a hooked fish, preparing to give a shake that would either tear him loose from the railing or snatch his leg from his body. Sobbing, Etta raised her weapon. ‘Damn you!’ she screamed, ‘Damn you, damn you, damn you!’ Her puny blade fell, but not as Kennit had expected. She did not waste the blow on the serpent’s heavily-scaled snout. Instead the blade cracked loudly against his weakened bone. She severed his leg just below the serpent’s teeth, cutting it off a nice bite, as it were. He saw blood gout from the ragged stump as she hauled him hastily backwards crabbing across the deck with him in her grip. He dimly heard the awe-stricken cries of his men as the serpent raised its head still higher, and then suddenly collapsed back into the sea, boneless as a piece of string. It would not rise again. It was dead. And Etta had fed it his leg.

‘Why did you do that?’ he demanded of her faintly. ‘What have I ever done to you that you would chop my leg off?’

‘Oh, my darling, oh, my love!’ she was caterwauling, even as the darkness swirled around him and took him down.

The slave-market stank. It was the worst smell that Wintrow had ever encountered. He wondered if the smell of one’s own kind in death and disease were naturally more offensive than any other odour. Instinctively, he wished to be away from here. It was a bone-deep revulsion. Despite the misery he saw, his sympathy and outrage were overwhelmed by his disgust. Hurry as he might, he could not seem to find an escape from this section of the city.

He had seen animals confined in large numbers before, even animals gathered together for slaughter, but their misery had been dumb and uncomprehending. They had chewed their cud and lashed their tails at flies as they awaited their fates. Animals could be held in pens or yards. They did not need to be secured with both manacles and leg-irons. Nor did animals shout or sob their misery and frustration in words.

‘I can’t help you, I can’t help you.’ Wintrow heard himself muttering the words aloud and bit down on his tongue. It was true, he assured himself. He could not help them. He could no more break their chains than they could. Even if he had been able to undo their fetters, what then? He could not erase the tattoos from their faces, could not help them flee and escape. Evil as their fates were, it was best if he left each one to face it and make the best he could of it. Some, surely, would find freedom and happiness later in their lives. This extreme of misery could not last for ever.

As if in agreement with that thought, a man passed him trundling a barrow. Three bodies had been dumped in it and despite their emaciation, the man pushed it with difficulty. A woman trailed after him, weeping disconsolately. ‘Please, please,’ she burst out as they passed Wintrow. ‘At least let me have his body. What good is it to you? Let me take my son home and bury him. Please, please.’ But the man pushing the barrow paid her no attention. Nor did anyone else in the hurrying, crowded street. Wintrow stared after them, wondering if perhaps the woman were crazy, perhaps it was not her son at all and the man with the barrow knew it. Or perhaps, he reflected, everyone else in the street was crazy, and had just seen a heartsick mother begging for the dead body of her son, and had done nothing about it. Including himself. Had he so swiftly become inured to human pain? He lifted his eyes and tried to see the street scene afresh.

It overwhelmed him. In the main part of the street, folk strolled arm in arm, dawdling to look at booths just as they might in any marketplace. They spoke of colour and size, of age and sex. But the livestock and goods they perused were human. There were simple coffles standing in courtyards, a string of people chained together, offered in lots or singles, for general work on farms or in town. At the corner of the courtyard, a tattooist plied his trade. He lounged in a chair beside a leather-lined head vice and an immense block of stone with an eye-bolt worked into it. For a reasonable price, the chant rose, a reasonable price, he would mark any newly-purchased slave with the buyer’s emblem. The boy calling this out was tethered to the stone. He wore only a loincloth, despite the winter day, and his entire body had been lavishly embellished with tattoos as a means of advertising his master’s skill. For a reasonable price, a reasonable price.

There were buildings that housed slaves, their specialities advertised on their swinging signs. Wintrow saw an emblem for carpenters and masons, another for seamstresses, and one that specialized in musicians and dancers. Just as any type of person might fall into debt, so one might acquire any type of slave. Tinker, tailor, soldier, sailor, Wintrow thought to himself. Tutors and wet-nurses and scribes and clerks. Why hire what you could buy outright? That seemed to be the philosophy here in the slave-market, yet Wintrow wondered how those shopping for slaves could not see themselves in their faces, or recognize one’s neighbours. No one else seemed disturbed by it. Some might hold a lace kerchief fastidiously to the nose, distressed by the odour. They did not hesitate to demand a slave stand, or walk, or trot in a circle the better to inspect him. Latticed-off areas were provided for the more private inspection of the females for sale. It seemed that, in the eyes of the buyers, a failure of finances instantly changed a man from a friend or neighbour into merchandise.

Some, it appeared, were not too badly housed and kept. They were the more valuable slaves, the well-educated and talented and skilled. Some few of those even appeared to take a quiet pride in their own worth, holding themselves with pride and assurance despite being marked with a tattoo across the face. Others were what Wintrow heard referred to as ‘map-faces’ meaning that the history of their owners could be traced by the progression of different tattoos. Usually such slaves were surly and difficult; tractable slaves often found permanent homes. More than five tattoos usually marked a slave as less than desirable. They were sold more cheaply and treated with casual brutality.

The face-tattooing of slaves, once regarded as a barbaric Chalcedean custom, was now the norm in Jamaillia City. It pained Wintrow to see how Jamaillia had not only adopted it, but adapted it. Those marketed as dancers and entertainers often bore only small and pale tattoos, easily masked with make-up so that their status would not disturb the pleasure of those being entertained. While it was illegal still to purchase slaves solely to prostitute them, the more exotic tattoos that marked some of them left no doubt in Wintrow’s mind as to what profession they’d been trained to. It was easier, often, to see their tattoos instead of meet their eyes.

It was while he was passing a street-corner coffle that a slave hailed him. ‘Please, priest! The comfort of Sa for the dying.’

Wintrow halted where he stood, unsure if he were the one addressed. The slave had stepped as far from his coffle as his fetters would allow. He did not look the sort of man who would seek Sa’s comfort; tattoos sprawled over his face and down his neck. Nor did he look as if he were dying. He was shirtless and his ribs showed and the fetter on his ankle had chafed the flesh there to running sores, but other than that, he looked tough and vital. He was substantially taller than Wintrow, a man of middle years, his body scarred by heavy use. His stance was that of a survivor. Wintrow glanced past him, to where his owner stood a short way off, haggling with a prospective buyer. The owner, a short man who spun a small club as he talked, caught Wintrow’s gaze briefly and scowled in displeasure, but did not leave off his bargaining.

‘You. Aren’t you a priest?’ the slave asked insistently.

‘I was training to be a priest,’ Wintrow admitted, ‘though I cannot fully claim that title as yet.’ More decisively he added, ‘But I am willing to give what comfort I can.’ He eyed the chained slaves and tried to keep suspicion from his voice as he asked, ‘Who needs such comfort?’

‘She does.’ The man stepped aside. A woman crouched miserably behind him. Wintrow saw then that the other slaves clustered around her, offering her the warmth and scant shelter of their gathered bodies. She was young, surely not more than twenty, and bore no visible injuries. She was the only woman in the group. Her arms were crossed over her belly, her head bowed down on her chest. When she lifted her face to regard him, her blue eyes were dull as riverstones. Her skin was very pale and her yellow hair had been chopped into a short brush on her head. The shift she wore was patched and stained. The shirt that shawled her shoulders probably belonged to the man who had summoned Wintrow. Like the man and the other slaves in the coffle, her face was overwritten with tattoos. She bore no traces of injury that Wintrow could easily see, nor did she appear frail. On the contrary, she was a well-muscled woman with wide shoulders. Only the lines of pain on her face marked her illness.

‘What ails you?’ Wintrow asked, coming closer. In some corner of his soul, he suspected the coffle of slaves were trying to lure him close enough to seize him. As a hostage, perhaps? But no one made any threatening moves. In fact, the slaves closest to the woman turned their backs to her as much as they could, as if to offer this token of privacy.

‘I bleed,’ she said quietly. ‘I bleed and it does not stop, not since I lost the child.’

Wintrow crouched down in front of her. He reached out to touch the back of her arm. There was no fever, in fact her skin was chill in the winter sunlight. He gently pinched a fold of her skin, marked how slowly the flesh recovered. She needed water or broth. Fluids. He sensed in her only misery and resignation. It did not feel like the acceptance of death. ‘Bleeding after childbirth is normal, you know.’ He offered her. ‘And after child loss as well. It should stop soon.’

She shook her head. ‘No. He dosed me too strong, to shake the child loose from me. A pregnant woman can not work as hard, you know. Her belly gets in the way. So they forced the dose down me and I lost the child. A week ago. But still I bleed, and the blood is bright red.’

‘Even a flow of bright red blood does not mean death. You can recover. Given the proper care, a woman can—’

Her bitter laugh cut off his words. He had never heard a laugh with so much of a scream in it.

‘You speak of women. I am a slave. No, a woman need not die of this, but I shall.’ She took a breath. ‘The comfort of Sa. That is all I am asking of you. Please.’ She bowed her head to receive it.

Perhaps in that moment Wintrow finally grasped what slavery was. He had known it for an evil, been schooled to the wickedness of it since his first days in the monastery. But now he saw it and heard the quiet resignation of despair in this young woman’s voice. She did not rail against the master who had stolen her child’s life. She spoke of his action as if it were the work of some primal force, a wind storm or river flood. His cruelty and evil did not seem to concern her. Only the end product she spoke of, the bleeding that would not cease, that she expected to succumb to. Wintrow stared at her. She did not have to die. He suspected she knew that as well as he did. If she were given a warm broth, bed and shelter, food and rest, and the herbs that were known to strengthen a woman’s parts, she would no doubt recover, to live many years and bear other children. But she would not. She knew it, the other slaves in her coffle knew it and he almost knew it. Almost knowing it was like pressing his hand to the deck to await the knife. Once the reality fell, he could never be the same again. To accept it would be to lose some part of himself.

He stood abruptly, his resolve strong, but when he spoke his words were soft.

‘Wait here and do not lose hope. I will go to Sa’s temple and get help. Surely your master can be made to see reason, that you will die without care.’ He offered a bitter smile. ‘If all else fails, perhaps we can persuade him a live slave is worth more than a dead one.’

The man who had first summoned him looked incredulous. ‘The temple? Small help we shall get there. A dog is a dog, and a slave is a slave. Neither is offered Sa’s comfort there. The priests there sing Sa’s songs, but dance to the Satrap’s piping. As to the man who sells our labour, he does not even own us. All he knows is that he gets a percentage of whatever we earn each day. From that, he feeds and shelters and doses us. The rest goes to our owner. Our broker will not make his piece smaller by trying to save Cala’s life. Why should he? It costs him nothing if she dies.’ The man looked down at Wintrow’s incomprehension and disbelief. ‘I was a fool to call to you.’ Bitterness crept into his voice. ‘The youth in your eyes deceived me. I should have known by your priest’s robe that I would find no willing help in you.’ He gripped Wintrow suddenly by the shoulder, a savagely hard pinch. ‘Give her the comfort of Sa. Or I swear I will break the bones in your collar.’

The strength of his clutch left Wintrow assured he could do it. ‘You do not need to threaten me,’ Wintrow gasped. He knew that the words sounded craven. ‘I am Sa’s servant in this.’

The man flung him contemptuously on the ground before the woman. ‘Do it then. And be quick.’ The man lifted a flinty gaze to stare beyond him. The broker and the customer haggled on. The customer’s back was turned to the coffle, but the broker faced them. He smiled with his mouth at some jest of his patron and laughed, ha, ha, ha, a mechanical sound, but all the while his clenched fist and the hard look he shot at his coffle promised severe punishment if his bargaining were interrupted. His other hand tapped a small bat against his leg impatiently.