Полная версия

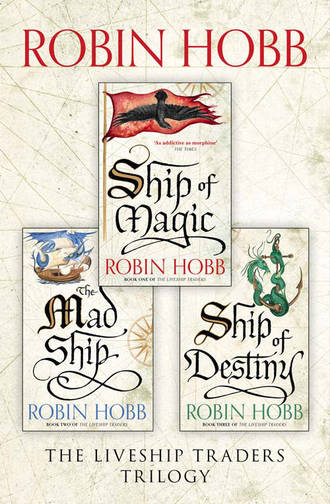

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

Caolwn smiled in return. ‘And if you do not have it, we shall adhere to our family’s original pledge. In blood or gold, the debt is owed. You shall forfeit a daughter or a grandchild to my family.’

There was no negotiating that. It had been pledged years ago, by Ephron’s grandmother. No Trader family would dream of going back on the given pledge of an ancestor. The nod she gave was a very stiff one, and the words she spoke she said carefully, binding the other woman with them. ‘But if I have for you a full sixteen measures of gold, then you will accept it as payment.’

Caolwn held out a bare hand in token of agreement. The lumps and wattles of flesh that depended from the fingers and knobbed the back of it were rubbery in Ronica’s grip as their handshake sealed them both to this new term. Caolwn stood.

‘Once more, Ronica of the Trader family Vestrit, I thank you for your trade. And for your hospitality.’

‘And once more, Caolwn of the Rain Wild family Festrew, I am pleased to have welcomed you and dealt with you. Family to family, blood to blood. Until we meet again, fare well.’

‘Family to family, blood to blood. May you fare well also.’

The formality of the words closed both their negotiations and the visit. Caolwn donned once more the summer cloak she had set aside. She pulled the hood up and well forward until all that remained of her features were the pale lavender lights of her eyes. A veil of lace was drawn down to cover them as well. As she drew on her loose gloves over her misshapen hands, she broke tradition. She looked down as she spoke. ‘It would not be so ill a fate as many think it, Ronica. Any Vestrit who joined our household I would treasure, as I have treasured our friendship. I was born in Bingtown, you know. And if I am no longer a woman that a man of your people could look upon without shuddering, know that I have not been unhappy. I have had a husband who treasured me, and borne a child, and seen her bear three healthy grandchildren to me. This flesh, the deformities… other women who stay in Bingtown perhaps pay a higher price for smooth skin and eyes and hair of normal hues. If all does not go as you pray it will, if next winter I take from you one of your blood… know that he or she will be cherished and loved. As much because that one comes of honourable stock and is a true Vestrit as because of the fresh blood he or she would bring to our folk.’

‘Thank you, Caolwn.’ The words almost choked Ronica. Sincere as the woman’s words might be, could she ever guess how they turned her bowels to ice inside her? Perhaps she did, for the lambent stare from within the hood blinked twice before Caolwn turned to the door. She took up the heavy wooden box of gold that awaited her by the threshold. Ronica unlatched the door for her. She knew better than to offer lantern or candle. The Rain Wild folk had no need of light on a summer’s night.

Ronica stood in her open doorway and watched Caolwn walk off into the darkness. A Rain Wild man shambled out from the shadows to join her. He took the wooden casket of gold and tucked it effortlessly under his arm. They both lifted a hand in farewell to her. She waved in return. She knew that on the beach there would be a small boat awaiting them, and farther out in the harbour a ship that bore but a single light. She wished them well, and hoped they would have a good journey. And she prayed fervently to Sa that she would never stand thus and watch one of her own walk off into darkness with them.

In the darkness, Keffria tried once again. ‘Kyle?’

‘Um?’ His voice was warm and deep, sweet with satiation.

She fitted her body closely to his. Her flesh was warm where they touched, chilled to delicious goosebumps where the summer breeze from the open window flowed over them. He smelled good, of sex and maleness, and the solid reality of his muscle and strength were a bulwark against all night fears. Why, she demanded silently of Sa, why couldn’t it all be this simple and good? He had come home this evening to say farewell to her, they had dined well and enjoyed wine together and then come together in both passion and love here. Tomorrow he would sail and be gone for however long it took him to make a trade circuit. Why did she have to spoil it with yet another discussion of Malta? Because, she told herself firmly, it had to be settled. She had to make him agree with her before he left. She would not go behind his back while he was gone. To do so would chip away the trust that had always bonded them.

So she took a deep breath and spoke the words they were both tired of hearing. ‘About Malta…’ she began.

He groaned. ‘No. Please, Keffria, no. In but a few hours I will have to rise and go. Let us have these last few hours together in peace.’

‘We haven’t that luxury. Malta knows we are at odds about this. She will use that as a lever on me the whole time you are gone. Whatever she wants that I forbid, she will reply, “But Papa said I am a woman now…” It will be torture for me.’

With a long-suffering sigh, he rolled away from her. The bed was suddenly a cooler place than it had been, uncomfortably cool. ‘So. I should take back my promise to her simply so you won’t be squabbling with her? Keffria. What will she think of me? Is this really so great a difficulty as you are making it out to be? Let her go to the one gathering in a pretty dress. That’s all it is.’

‘No.’ It took all her courage to contradict him directly. But he didn’t know what he was talking about, she told herself frantically. He didn’t understand, and she’d left it too late to explain it all to him tonight. She had to make him give in to her, just this once. ‘It’s far more than dancing with a man in a pretty dress. She’s having dance lessons from Rache. I want to tell her that she must be content with that for now, that she must spend at least a year preparing to be seen as a woman in Bingtown society before she can go out as one. And I want to tell her that you and I are united in this. That you thought it over and changed your mind about letting her go.’

‘But I didn’t,’ Kyle pointed out stubbornly. He was on his back now, staring up at the ceiling. He had lifted his hands and laced the fingers behind his head. Were he standing up, she thought, he’d have his arms crossed on his chest. ‘I think you are making much of a small thing. And… I don’t say this to hurt you, but because I see it more and more in you… I think you simply do not wish to give up any control of Malta, that you wish to keep her a little girl at your side. I sense it almost as a jealousy in you, dear. That she vies for my attention, as well as the attentions of young men. I’ve seen it before; no mother wishes to be eclipsed by her daughter. A grown daughter must always be a reminder to a woman that she is not young anymore. But I think it is unworthy of you, Keffria. Let your daughter grow up and be both an ornament and a credit to you. You cannot keep her in short skirts and plaited hair for ever.’

Perhaps he took her furious and affronted silence for something else, for he turned slightly toward her as he said, ‘We should be grateful she is so unlike Wintrow. Look at him. He not only looks and sounds like a boy, but longs to continue being one. Just the other day, aboard the ship, I came upon him working shirtless in the sun. His back was red as a lobster and he was sulking as furiously as a five year old. Some of the men, as a bit of a jest, had taken his shirts and pegged them up at the top of the rigging. And he feared to go up to get them back. I called him to my chamber and tried to explain to him, privately, that if he did not go up after them, the rest of the crew would think him a coward. He claimed it was not fear that kept him from going after his shirt but dignity. Standing there like a righteous little prig of a preacher! And he tried to make some moral point of it, that it was neither courage nor cowardice, but that he would not risk himself for their amusement. I told him there was very little risk to it, did he but heed what he’d been taught, and again he came back at me with some cant about no man should put another man even to a small risk simply for his own amusement. Finally, I lost patience with him and called Torg and told him to see the boy up the mast and back to get his shirt. I fear he lost a great deal of the crew’s respect over that…’

‘Why do you allow your crew to play boy’s pranks when they ought to be about their work?’ Keffria demanded. Her heart bled for Wintrow even as she fervently wished her son had simply gone after his own shirt. If he’d but risen to their challenge, they would have seen him as one of their own. Now they would see him as an outsider to torment. She knew it instinctively, and wondered that he had not.

‘You’ve fair ruined the lad by sending him off to the priests.’ Kyle sounded almost satisfied as he said this, and she suddenly realized how completely he had changed the topic.

‘We were discussing, not Wintrow, but Malta.’ A new tack suddenly occurred to her. ‘As you have insisted that only you know the correct way to raise our son in the ways of men, perhaps you should concede that only a woman can know the best way to guide Malta into womanhood.’

Even in the darkness, she could see the surprise that crossed his face at the tartness of her tone. It was, she suddenly knew, the wrong way to approach him if she wanted to win him to her side. But the words had been said and she was suddenly too angry to take them back. Too angry to try to cajole and coax him to her way of thinking.

‘If you were a different type of woman, I might concede the right of that,’ he said coldly. ‘But I recall you as you were when you were a girl. And your own mother kept you tethered to her skirts much as you seek to restrain Malta. Consider how long it took me to awaken you to a woman’s feelings. Not all men have that patience. I would not see Malta grow up as backward and shy as you were.’

The cruelty of his words took her breath away. Their slow courtship, her deliciously gradual hope and then certainty of Kyle’s interest in her were some of her sweetest memories. He had snatched that away in a moment, turned her months of shy anticipation into some exercise of bored patience on his part, made his awakening of her feelings an educational service he had performed for her. She turned her head and stared at this sudden stranger in her bed. She wanted to deny that he had ever spoken such words, wanted to pretend that they did not truly reflect his feelings but had been said out of some kind of spite. Coldness welled up from within her now. Spite words or true, did not it come to the same thing? He was not the man she had always believed him to be. All these years, she had been married to a fantasy, not a real person. She had imagined a husband to herself, a tender, loving, laughing man who only stayed away so many months because he must, and she had put Kyle’s face on her creation. Easy enough to ignore or excuse a few flaws or even a dozen when he made one of his brief stops at home. She had always been able to pretend he was tired, that the voyage had been both long and hard, that they were simply getting readjusted to one another. Despite all the things he had said and done in the weeks since her father’s death, she had continued to treat him and react to him as if he were the man she had created in her mind. The truth was that he had never been the romantic figure her fancies had made him. He was just a man, like any other man. No. He was stupider than most.

He was stupid enough to think she had to obey him. Even when she knew better, even when he was not around to oppose her. Realizing this was like opening her eyes to the sun’s rising. How had it never occurred to her before?

Perhaps Kyle sensed that he had pushed her a bit too far. He rolled towards her, reached out across the glacial sheets to touch her shoulder. ‘Come here,’ he bade her in a comforting voice. ‘Don’t be sulky. Not on my last night at home. Trust me. If all goes as it should on this voyage, I’ll be able to stay home for a while next time we dock. I’ll be here, to take all this off your shoulders. Malta, Selden, the ship, the holdings… I’ll put all in order and run them as they should always have been run. You have always been shy and backward… I should not say that to you as if it were a thing you could change in yourself. I just want to let you know that I know how hard you have tried to manage things in spite of that. If anyone is at fault, it is I, to have let these concerns have been your task all these years.’

Numbed, she let him draw her near to him, let him settle against her to sleep. What had been his warmth was suddenly a burdensome weight against her. The promises he had just made to reassure her instead echoed in her mind like a threat.

Ronica Vestrit opened her eyes to the shadowy bedroom. Her window was open, the gauzy curtains moving softly with the night wind. I sleep like an old woman now, she thought to herself. In fits and starts. It isn’t sleeping and it isn’t waking and it isn’t rest. She let her eyes close again. Maybe it was from all those months spent by Ephron’s bedside, when she didn’t dare sleep too deeply, when if he stirred at all she was instantly alert. Maybe, as the empty lonely months passed, she’d be able to unlearn it and sleep deep and sound again. Somehow she doubted it.

‘Mother.’

A whisper light as a wraith’s sigh. ‘Yes, dear. Mother’s here.’ Ronica replied to it as quietly. She did not open her eyes. She knew these voices, had known them for years. Her little sons still sometimes came, to call to her in the darkness. Painful as such fancies were, she would not open her eyes and disperse them. One held on to what comforts one had, even if they had sharp edges.

‘Mother, I’ve come to ask your help.’

Ronica opened her eyes slowly. ‘Althea?’ she whispered to the darkness. Was there a figure just outside the window, behind the blowing curtains. Or was this just another of her night fancies?

A hand reached to pull the curtain out of the way. Althea leaned in on the sill.

‘Oh, thank Sa you’re safe!’

Ronica rolled hastily from her bed, but as she stood up, Althea retreated from the window. ‘If you call Kyle, I’ll never come back again,’ she warned her mother in a low, rough voice.

Ronica came to the window. ‘I wasn’t even thinking of calling Kyle,’ she said softly. ‘Come back. We have to talk. Everything’s gone wrong. Nothing’s turned out the way it was supposed to.’

‘That’s hardly news,’ Althea muttered darkly. She ventured closer to the window. Ronica met her gaze, and for an instant she looked down into naked hurt. Then Althea looked away from her. ‘Mother… maybe I’m a fool to ask this. But I have to, I have to know before I begin. Do you recall what Kyle said, when… the last time we were all together?’ Her daughter’s voice was strangely urgent.

Ronica sighed heavily. ‘Kyle said a great many things. Most of which I wish I could forget, but they seem graven in my memory. Which one are you talking about?’

‘He swore by Sa that if even one reputable captain would vouch for my competency, he’d give my ship back to me. Do you remember that he said that?’

‘I do,’ Ronica admitted. ‘But I doubt that he meant it. It’s just his way, to throw such things about when he is angry.’

‘But you do remember him saying it?’ Althea pressed.

‘Yes. Yes, I remember he said that. Althea, we have much more important things to discuss than this. Please. Come in. Come back home, we need to…’

‘No. Nothing is more important than what I just asked you. Mother, I’ve never known you to lie. Not when it was important. The time will come when I’ll be counting on you to tell the truth.’ Incredibly, her daughter was walking away, speaking over her shoulder as she went. For one frightening instant, she looked so like her father as a young man. She wore the striped shirt and black trousers of a sailor on shore. She even walked as he had, that roll to her gait, and the long dark queue of hair down her back.

‘Wait!’ Ronica called to her. She sat down on the window sill and swung her legs over it. ‘Althea, wait!’ she cried out, and jumped down into the garden. She landed badly, her bare feet protesting the rocky walk under her window. She nearly fell, but managed to catch herself. She hastened across a sward of green to the thick laurel hedge that bounded it. But when she reached it, Althea was already gone. Ronica set her hands to that dense, leafy barrier and tried to push through it. It yielded, but only a little and scratchily. The leaves were wet with dew.

She stepped back from it and looked around the night garden. All was silence and stillness. Her daughter was gone again. If she had ever really been here at all.

Sessurea was the one the tangle chose to confront Maulkin. It both angered and wounded Shreever that they had so obviously been conferring amongst themselves. If one had a doubt, why had not that one come to speak of it to Maulkin himself, rather than sharing the poisonous idea with the others? Now they were all crazed with it, as if they had partaken of tainted meat. The foolishness was most strong in Sessurea, for as he whipped himself into position to challenge Maulkin, his orange mane was already erect and toxic.

‘You lead us awry!’ he trumpeted. ‘Daily the Plenty grows shallower and warmer, and the salts of it more strange. You lead us where prey is scarce and then give us scant time to feed. I scent no other tangles, for no others have come this way. You lead us not to rebirth but to death.’

Shreever shook out her ruff, arching her neck to release her poisons. If Maulkin were attacked by the others, she vowed he would not fight alone. But Maulkin did not even erect his ruff. As lazily as weed in the tides, he wove a slow pattern in the Plenty. It carried him over and then under Sessurea, who twined his own head about in an effort to keep his gaze upon Maulkin. Before the whole tangle, he changed Sessurea’s challenge into a graceful dance in which Maulkin led.

His wisdom was as entwining as his movement when he addressed Sessurea. ‘If you scent no other tangle, it is because I follow the scent of those who passed here an age ago. But if you opened wide your gills, you would scent others, and not so far ahead of us. You fear the warmth of this Plenty, and yet you were among those who first protested when I led you from warmth to coolness. You taste the strangeness of the salts and think we have gone awry. Foolish serpent! If all were familiar, then we would be swimming back into yesterday. Follow me, and do not doubt any longer. For I lead you, not into your own familiar yesterday, but into tomorrow, and the yesterday of your ancestors. Doubt no longer, but swallow my truth!’

So close had Maulkin come to Sessurea as he wove his dance and wisdom that when he lifted his mane and released his toxins, Sessurea breathed them in. His great green eyes spun as he tasted the echo of death and the truth that hides in it. He faltered in his defence, going limp, and would have sunk to the bottom had not Maulkin wrapped his length with his own. Yet even as he bore up the one who would have denied him, the tangle cried out in unease. For above the Plenty and yet in it, and below the Lack and yet in it, a great darkness moved. Its shadow passed over them soundlessly save for the rush of its finless body.

Yet when the rest of the tangle would have fled back into the depths, Maulkin upheld Sessurea and pursued the shape. ‘Come!’ he trumpeted back to them all. ‘Follow! Follow without fear, and I promise you both food and rebirth when the time for the gathering is upon us!’

Shreever mastered her fear only with her loyalty to Maulkin. Of all the tangle, she first uncoiled herself to flow through the Plenty and follow their leader. She watched the first shivering of awareness come back to Sessurea, and marked how gently he parted himself from Maulkin. ‘I saw this,’ he called back to the others who still lagged and hesitated. ‘This is right, Maulkin is right! I have seen this in his memories, and now we live it again. Come. Come.’

At that acknowledgement, there came forth from the shape food, prey that neither struggled nor swam, but drifted down to be seized and consumed by all.

‘We shall not starve,’ Maulkin assured his followers quietly. ‘Nor shall we need to delay our journey for fishing. Set aside your doubts and reach for your deepest memories. Follow.’

16 NEW ROLES

THE SHIP CRESTED THE WAVE, her bow rising as if she would ascend into the tortured sky itself. Sa knew, the rain was near heavy enough to float a ship. For a long hanging instant, Althea could see nothing but sky. In the next instant, they were rushing headlong down a long slope of water into a deep trough. It seemed as if they must plunge into the rising wall of water, and plunge they did, green water covering the deck. The impact jarred the mast, and with it the yard that Althea clung to. Her numbed fingers slipped on the wet cold canvas. She curled her feet about the footrope she had braced them on and made her grip more firm. Then with a shudder, the ship was shaking it off, rising through the water and rushing up the next mountain.

‘Ath! Move it!’ The voice came from below her. On the ratlines, Reller was glaring at her, eyes squinted against the wind and rain. ‘You in trouble, boy?’

‘No. I’m coming,’ she called back. She was cold and wet and incredibly tired. The other hands had finished their tasks and fled down the rigging. Althea had paused a moment to cling where she was and gather some strength for the climb down. At the beginning of her watch, at first sight of storm, the captain had ordered the sails hauled down and clewed up. The rain hit them first, followed by wind that seemed bent on picking them out of the rigging. They had no sooner finished and regained the deck than the cry came to double reef the topsails and furl everything else. In seeming response to their efforts, the storm grew worse. Her watch had clambered about the rigging like ants on floating debris, clewing down, close reefing and furling in response to order after order, until she had stopped thinking at all, only moving to obey the bellowed commands. She had not forgotten why she was there; of their own accord, her hands had packed the wet canvas and secured it. Amazing, what the body could do even when the mind was numbed by weariness and fear. Her hands and feet were like cleverly-trained animals now that contrived to keep her alive despite her own ambivalence.

She made her slow way down, the last to be clear of the rigging as always. The others had passed her on the way down and were most likely already below. That Reller had even bothered to ask her if she was in trouble marked him as far more considerate than the rest. She had no idea why the man seemed to keep an eye on her, but she felt at once grateful and humiliated by it.

When she had first joined the ship’s crew, she had been burning to distinguish herself. She had driven herself to do more, faster and better. It had seemed wonderful to be back on a deck again. Repetitious food, badly stored; crowded and smelly living conditions; even the crudity of those she was forced to call shipmates had all seemed tolerable in her first days aboard. She was back at sea, she was doing something, and at the end of the voyage she’d have a ship’s ticket to rub in Kyle’s face. She’d show him. She’d regain her ship, she promised herself, and resolutely set out to learn this new ship as swiftly as she could.

But despite her best efforts, her inexperience on such a vessel was multiplied by the lesser size of her body. This was a slaughter-ship, not a merchant-trader. The captain’s objective was not to get swiftly from one place to another to deliver goods, but to cruise a zig-zag path looking for prey. The ship carried a far larger crew than would a merchant-ship of the same size, for in addition to sailing, there must be enough hands to hunt, slaughter, render and stow the harvested meat and oil below. Hence the ship was more crowded and less clean. She had held fast to her resolution to learn fast and well, but determination alone could not make her the best sailor on this stinking carrion ship. She knew, in some dim back part of her mind, that she had vastly improved her skills and stamina since signing on to the Reaper. She also knew that what she had achieved was still not enough to make her what her father would have called ‘a smart lad’. Her purposefulness had wallowed down into despair. Then she had lost even that. Now she survived from day-to-day, and thought of little more than that.