Полная версия

Pilgrim

SARA DOUGLASS

Pilgrim

Book Two of the Wayfarer Redemption

Contents

Cover

Title Page

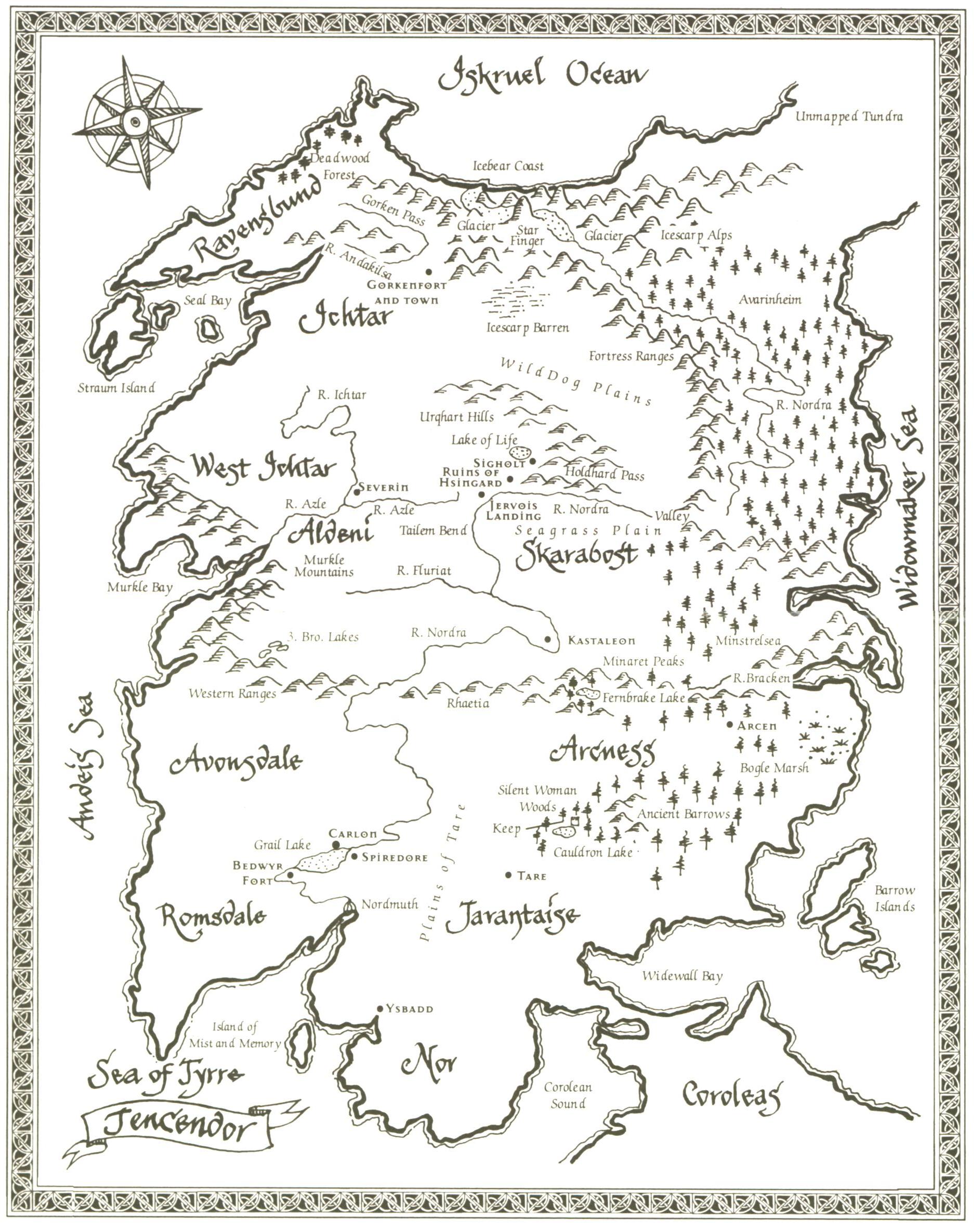

Map

Prologue

1. Questions of Conveyance

2. The Dreamer

3. The Feathered Lizard

4. What To Do?

5. The Prodigal Son’s Welcome

6. The Rosewood Staff

7. The Emperor’s Horses

8. Towards Cauldron Lake

9. Cauldron Lake

10. The Crystal Forest

11. GhostTree Camp

12. The Hawkchilds

13. The Waiting Stars

14. In the Chamber of the Enemy

15. Hidden Conversations

16. Destruction Accepted

17. The Donkeys’ Tantrum

18. Shade

19. The SunSoar Curse

20. Sicarius

21. Why? Why? Why?

22. Arrival at the Minaret Peaks

23. The Arcness Plains

24. The Dark Trap

25. Askam

26. The Hall of the Stars

27. Drago’s Ancient Relics

28. Sunken Castles

29. The Mountain Trails

30. Home Safe

31. The Fun of the Blooding

32. A Seal Hunt … of Sorts

33. Of Sundry Travellers

34. Poor, Useless Fool

35. Andeis Voyagers

36. Gorkenfort

37. The Lesson of the Sparrow

38. The Sunken Keep

39. The Mother of Races

40. Murkle Mines

41. An Angry Foam of Stars

42. The Lake of Life

43. The Bridges of Tencendor

44. Aftermath

45. The Twenty Thousand

46. The Secret in the Basement

47. StarSon

48. Companionship and Respect

49. Sigholt’s Gift

50. Sanctuary

51. A SunSoar Reunion … of Sorts

52. Of What Can’t Be Rescued

53. The Enchanted Song Book

54. The Cruelty of Love

55. An Enchantment Made Visible

56. The Field of Flowers

57. Gorken Pass

58. The Deep Blue Cloak of Betrayal

59. A Fate Deserved?

60. Of Salvation

61. The Bloodied Rose Wind

62. A Song of Innocence

63. The Fields of Resurrection … and the Streets of Death

64. The Doorways

65. Evacuation

66. Cats in the Corridor!

67. The Emptying

68. Mountain, Forest and Marsh

69. The Dark Tower

70. The Rape of Tencendor

71. The Hunt

Epilogue

Glossary

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Author’s Note

Also by Sara Douglass

Copyright

About the Publisher

Map

Prologue

The lieutenant pushed his fork back and forth across the table, back and forth, back and forth, his eyes vacant, his mind and heart a thousand galaxies away. Scrape … scrape … scrape.

“For heaven’s sake, Chris, will you stop that? It’s driving me crazy!”

The lieutenant gripped the fork in his fist, and his companion tensed, thinking Chris would fling it across the dull, black metal table towards him.

But Chris’ hand suddenly relaxed, and he managed a tight, half-apologetic smile. “Sorry. It’s just that this … this …”

“We only have another two day spans, mate, and then we wake the next shift for their stint at uselessness.”

Chris’ fingers traced gently over the surface of the table. It vibrated. Everything on the ship vibrated.

“I can’t bloody wait for another stretch of deep sleep,” he said quietly, his eyes flickering over to Commander Devereaux sitting at a keyboard by the room’s only porthole. “Unlike him.”

His fellow officer nodded. Perhaps thirty-five rotations ago, waking from their allotted span of deep sleep, the retiring crew had reported a strange vibration within the ship. No mechanical or structural problem … the ship was just vibrating.

And then … then they’d found that the ship was becoming a little sluggish in responding to commands, and after five or six day spans it refused to respond to their commands at all.

The other three ships in the fleet had similar problems — at least, that’s what their last communiques had reported. The Ark crew were aware of the faint phosphorescent outlines in the wake of the other ships, but that was all now. So here they were, hurtling through deep space, in ships that responded to no command, and with cargo that the crews preferred not to think about. When they volunteered for this mission, hadn’t they been told that once they’d found somewhere to “dispose” of the cargo they could come home?

But now, the crew of The Ark wondered, what would be disposed of? The cargo? Or them?

It might have helped if the commander had come up with something helpful. But Devereaux seemed peculiarly unconcerned, saying only that the vibrations soothed his soul and that the ships, if they no longer responded to human command, at least seemed to know what they were doing.

And now here he was, tapping at that keyboard as if he actually had a purpose in life. None of them had a purpose any more. They were as good as dead. Everyone knew that. Why not Devereaux?

“What are you doing, sir?” Chris asked. He had picked up the fork again, and it quivered in his over-tight grip.

“I …” Devereaux frowned as if listening intently to something, then his fingers rattled over the keys. “I am just writing this down.”

“Writing what down, sir?” the other officer asked, his voice tight.

Devereaux turned slightly to look at them, his eyes wide. “Don’t you hear it? Lovely music … enchanted music … listen, it vibrates through the ship. Don’t you feel it?”

“No,” Chris said. He paused, uncomfortable. “Why write it down, sir? For who? What is the bloody point of writing it down?”

Devereaux smiled. “I’m writing it down for Katie, Chris. A song book for Katie.”

Chris stared at him, almost hating the man. “Katie is dead, sir. She has been dead at least twelve thousand years. I repeat, what is the fucking point?”

Devereaux’s smile did not falter. He lifted a hand and placed it over his heart. “She lives here, Chris. She always will. And in writing down these melodies, I hope that one day she will live to enjoy the music as much as I do.”

It was then that The Ark, in silent communion with the others, decided to let Devereaux live.

1 Questions of Conveyance

The speckled blue eagle clung to rocks under the overhang of the river cliffs a league south of Carlon. He shuddered. Nothing in life made sense any more. He had been drifting the thermals, digesting his noonday meal of rats, when a thin grey mist had enveloped him and sent despair stringing through his veins.

He could not fight it, and had not wanted to. His wings crippled with melancholy, he’d plummeted from the sky, uncaring about his inevitable death.

It had seemed the best solution to his useless life.

Chasing rats? Ingesting them. Why?

In his mad, uncaring tumble out of control, the eagle struck the cliff face. The impact drove the breath from him, and he thought it may also have broken one of his breast bones, but even in the midst of despair, the eagle’s talons scrabbled automatically for purchase among the rocks.

And then … then the despair had gone. Evaporated.

The eagle blinked and looked about.

It was cold here in the shadow of the rocks, and he wanted to warm himself in the sun again — but he feared the grey-fingered enemy that awaited him within the thermals. In the open air.

What was this grey miasma? What had caused it?

He cocked his head to one side, his eyes unblinking, considering. Gryphon? Was this their mischief?

No. The Gryphon had long gone, and their evil he would have felt ripping into him, not seeping in with this grey mist’s many-fingered coldness. No, this was something very different.

Something worse.

The sun was sinking now, only an hour or two left until dusk, and the eagle did not want to spend the night clinging to this cliff face.

He cocked his head — the grey haze had evaporated.

With fear — a new sensation for this most ancient and wise of birds — he cast himself into the air. He rose over the Nordra, expecting any minute to be seized again by that consuming despair.

But there was nothing.

Nothing but the rays of the sun glinting from his feathers and the company of the sky.

Relieved, the eagle tilted his wings and headed for his roost under the eaves of one of the towers of Carlon.

He thought he would rest there a day or two. Watch. Discover if the evil would strike again, and, if so, how best to survive it.

The yards of the slaughterhouse situated a half-league west of Tare were in chaos. Two of the slaughtermen had been outside when Sheol’s mid-afternoon despair struck. Now they were dead, trampled beneath the hooves of a thousand crazed livestock. The fourteen other men were still safe, for they had been inside and protected when the TimeKeepers had burst through the Ancient Barrows.

Even though mid-afternoon had passed, and the world was once more left to its own devices, the men did not dare leave the safety of the slaughterhouse.

Animals ringed the building. Sheep, a few pigs, seven old plough horses, and innumerable cattle — all once destined for death and butchery. All staring implacably, unblinkingly, at the doors and windows.

One of the pigs nudged at the door with his snout, and then squealed.

Instantly pandemonium broke out. A horse screamed, and threw itself at the door. The wooden planks cracked, but did not break.

Imitating the horse’s lead, cattle hurled themselves against the door and walls.

The slaughtermen inside grabbed whatever they could to defend themselves.

The walls began to shake under the onslaught. Sheep bit savagely at any protuberance, pulling nails from boards with their teeth, and horses rent at walls with their hooves. All the animals wailed, one continuous thin screech that forced the men inside to drop their weapons and clasp hands to ears, screaming themselves.

The door cracked once more, then split. A brown steer shouldered his way through. He was plump and healthy, bred and fattened to feed the robust appetites of the Tarean citizens. Now he had an appetite himself.

Behind him many score cattle trampled into the slaughterhouse, pigs and sheep squeezing among the legs of their bovine cousins as best they could.

The invasion was many bodied, but it acted with one mind.

The slaughtermen did not die well.

The creatures used only their teeth to kill, not their hooves, and those teeth were grinders, not biters, and so those men were ground into the grave, and it was not a fast nor pleasant descent.

Of all the creatures once destined for slaughter, only the horses did not enter the slaughterhouse and partake of the meal.

They lingered outside in the first of the collecting yards, nervous, unsure, their heads high, their skin twitching. One snorted, then pranced about a few paces. He’d not had this much energy since he’d been a yearling.

A shadow flickered over one of the far fences, then raced across the trampled dirt towards the group of horses. They bunched together, turning to watch the shadow, and then it swept over them and the horses screamed, jerked, and then stampeded, breaking through the fence in their panic.

High above, the flock of Hawkchilds veered to the east and turned their eyes once more to the Ancient Barrows.

Their masters called.

The horses fled, running east with all the strength left in their hearts.

At the slaughterhouse, a brown and cream badger ambled into the bloodied building and stood surveying the carnage.

You have done well, he spoke to those inside. Would you like to exact yet more vengeance?

Sheol tipped back her head and exposed her slim white throat to the afternoon sun. Her fingers spasmed and dug into the rocky soil of the ruined Barrow she sat on, her body arched, and she moaned and shuddered.

A residual wisp of grey miasma still clung to a corner of her lip.

“Sheol?” Raspu murmured and reached out a hand. “Sheol?” At the soft touch of his hand, Sheol’s sapphire eyes jerked open and she bared her teeth in a snarl.

Raspu did not flinch. “Sheol? Did you feast well?”

The entire group of TimeKeeper Demons regarded her curiously, as did StarLaughter sitting slightly to one side with a breast bared, its useless nipple hanging from her undead child’s mouth.

Sheol blinked, and then her snarl widened into a smile, and the reddened tip of her tongue probed slowly at the corners of her lips.

She gobbled down the remaining trace of mist.

“I fed well!” she cried, and leapt to her feet, spinning about in a circle. “Well!”

Her companions stared at her, noting the new flush of strength and power in her cheeks and eyes, and they howled with anticipation. Sheol began an ecstatic caper, and the Demons joined her in dance, holding hands and circling in tight formation through the rubble of earth and rocks that had once been the Barrow. They screamed and shrieked, intoxicated with success.

The Minstrelsea forest, encircling the ruined spaces of the Ancient Barrows, was silent. Listening. Watching.

StarLaughter pulled the material of her gown over her breast and smiled for her friends. It had been eons since they had fed, and she could well understand their excitement. They had sat still and silent as Sheol’s demonic influence had issued from her nostrils and mouth in a steady effluence of misty grey contagion. The haze had coalesced about her head for a moment, blurring her features, and had then rippled forth with the speed of thought over the entire land of Tencendor.

Every soul it touched — Icarii, human, bird or animal — had been infected, and Sheol had fed generously on each one of them.

Now how well Sheol looked! The veins of her neck throbbed with life, and her teeth were whiter and her mouth redder than StarLaughter had ever seen. Stars, but the others must be beside themselves in the wait for their turn!

StarLaughter rose slowly to her feet, her child clasped protectively in her hands. “When?” she said.

The Demons stopped and stared at her.

“We need to wait a few days,” Raspu finally replied.

“What?” StarLaughter cried. “My son —”

“Not before then,” Sheol said, and took a step towards StarLaughter. “We all need to feed, and once we have grown the stronger for the feeding we can dare the forest paths.”

She cast her eyes over the distant trees and her lip curled. “We will move during our time, and on our terms.”

“You don’t like the forest?” StarLaughter said.

“It is not dead,” Barzula responded. “And it is far, far too gloomy.”

“But —” StarLaughter began.

“Hush,” Rox said, and he turned flat eyes her way. “You ask too many questions.”

StarLaughter closed her mouth, but she hugged her baby tightly to her, and stared angrily at the Demons. Sheol smiled, and patted StarLaughter on the shoulder. “We are tense, Queen of Heaven. Pardon our ill manners.”

StarLaughter nodded, but Sheol’s apology had done little to appease her anger.

“Why travel the forest if you do not like it,” she said. “Surely the waterways would be the safest and fastest way to reach Cauldron Lake.”

“No,” Sheol said. “Not the waterways. We do not like the waterways.”

“Why not?” StarLaughter asked, shooting Rox a defiant look.

“Because the waterways are the Enemy’s construct, and they will have set traps for us,” Sheol said. “Even if they are long dead, their traps are not. The waterways are too closely allied with —”

“Them,” Barzula said.

“— their voyager craft,” Sheol continued through the interruption, “to be safe for us. No matter. We will dare the forests … and survive. After Cauldron Lake the way will be easier. Not only will we be stronger, we will be in the open.”

All of the Demons relaxed at the thought of open territory.

“Soon my babe will live and breath and cry my name,” StarLaughter whispered, her eyes unfocused and her hands digging into the babe’s cool, damp flesh.

“Oh, assuredly,” Sheol said, and shared a secret wink with her companion Demons. She laughed. “Assuredly!”

The other Demons howled in shared merriment, and StarLaughter smiled, thinking she understood.

Then as one the Demons quietened, their faces falling still. Rox turned slowly to the west. “Hark,” he said. “What is that?”

“Conveyance,” said Mot.

If the TimeKeeper Demons did not like to use the waterways, then WolfStar had no such compunction. When he’d slipped away from the Chamber of the Star Gate, he’d not gone to the surface, as had everyone else. Instead, WolfStar had faded back into the waterways. They would protect him as nothing else could; the pack of resurrected children would not be able to find him down here. And WolfStar did not want to be found, not for a long time.

He had something very important to do.

Under one arm he carried a sack with as much tenderness and care as StarLaughter carried her undead infant. The sack’s linen was slightly stained, as if with effluent, and it left an unpleasant odour in WolfStar’s wake.

Niah, or what was left of her.

Niah … WolfStar’s face softened very slightly. She had been so desirable, so strong, when she’d been the First Priestess on the Isle of Mist and Memory. She’d carried through her task — to bear Azhure in the hateful household of Hagen, the Plough Keeper of Smyrton — with courage and sweetness, and had passed that courage and sweetness to their enchanted daughter.

For that courage WolfStar had promised Niah rebirth and his love, and he’d meant to give her both.

Except things hadn’t turned out quite so well as planned. Niah’s manner of death (and even WolfStar shuddered whenever he thought of it) had warped her soul so brutally that she’d been reborn a vindictive, hard woman. So determined to re-seize life that she cared not what her determination might do to the other lives she touched.

Not the woman WolfStar had thought to love. True, the re-born Niah been pleasing enough, and eager enough, and WolfStar had adored her quickness in conceiving of an heir, but …

… but the fact was she’d failed. Failed WolfStar and failed Tencendor at the critical moment. WolfStar had thought of little else in the long hours he’d wandered the dank and dark halls of the waterways. Niah had distracted him when his full concentration should have been elsewhere (could he have stopped Drago if he hadn’t been so determined to bed Niah?), and her inability to keep her hold on the body she’d gained meant that WolfStar had again been distracted — with grief! damn it! — just when his full power and attention was needed to help ward the Star Gate.

Niah had failed because Zenith had proved too strong. Who would have thought it? True, Zenith had the aid of Faraday, and an earthworm could accomplish miracles if it had Faraday to help it, but even so … Zenith had been the stronger, and WolfStar had always been the one to be impressed by strength.

Ah! He had far more vital matters to think of than pondering Zenith’s sudden determination. Besides, with what he planned, he could get back the woman he’d always meant to have. Alive. Vibrant. And very, very powerful.

His fingers unconsciously tightened about the sack.

This time Niah would not fail.

WolfStar grinned, feral and confident in the darkness.

“Here,” he muttered, and ducked into a dark opening no more than head height.

It was an ancient drain, and it lead to the bowels of the Keep on the shores of Cauldron Lake.

WolfStar knew exactly what he had to do.

The horses ran, and their crippled limbs ate up the leagues with astonishing ease. Directly above them flew the Hawkchilds, so completely in unison that as one lifted his wings, so all lifted, and as another swept hers down, so all swept theirs down.

Each stroke of their wings corresponded exactly with a stride of the horses.

And with each stroke of the Hawkchilds’ wings, the horses felt as if they were lifted slightly into the air, and their strides lengthened so that they floated a score of paces with each stride. When their hooves beat earthward again, they barely grazed the ground before they powered effortlessly forward into their next stride.

And with each stride, the horses felt life surge through their veins and tired muscles. Necks thickened and arched, nostrils flared crimson, sway-backs straightened and flowed strong into newly muscled haunches. Hair and skin darkened and fined, until they glowed a silky ebony.

Strange things twisted inside their bodies, but of those changes there was, as yet, no outward sign.

Once fit only for the slaughterhouse, great black war horses raced across the plains, heading for the Ancient Barrows.

2 The Dreamer

The bones had lain there for almost twenty years, picked clean by scavengers and the passing winds of time. They had been a neat pile when the tired old soul had lain down for the final time; now they were scattered over a half-dozen paces, some resting in the glare of the sun, others piled under the gloom of a thorn bush.

Footsteps disturbed the peace of the grave site. A tall and willowy woman, dressed in a clinging pale grey robe. Iron-grey hair, streaked with silver, cascaded down her back. On the ring finger of her left hand she wore a circle of stars. She had very deep blue eyes and a red mouth, with blood trailing from one corner and down her chin.

As she neared the largest pile of bones the woman crouched, and snarled, her hands tensed into tight claws.

“Fool way to die!” she hissed. “Alone and forgotten! Did you think I forgot? Did you think to escape me so easily?”

She snarled again, and grabbed a portion of the rib cage, flinging it behind her. She snatched at another bone, and threw that with the ribs. She scurried a little further away, reached under the thorn bush and hauled out its desiccated treasury of bones, also throwing them on the pile.