Полная версия

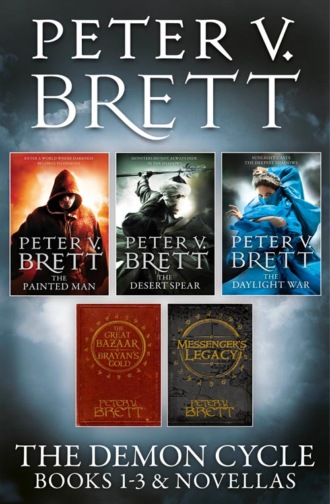

The Demon Cycle Books 1-3 and Novellas: The Painted Man, The Desert Spear, The Daylight War plus The Great Bazaar and Brayan’s Gold and Messenger’s Legacy

‘I can read to those who can’t, ma’am,’ Ragen said, ‘but I don’t know your town well enough to distribute.’

‘No need,’ Selia said, pulling Arlen forward. ‘Arlen here will take you to the general store in Town Square. Give the letters and packages to Rusco Hog when you deliver the salt. Most everyone will come running now that the salt’s in, and Rusco’s one of the few in town with letters and numbers. The old crook will complain and try to insist on payment, but you tell him that in time of trouble, the whole town must throw in. You tell him to give out the letters and read to those who can’t, or I’ll not lift a finger the next time the town wants to throw a rope around his neck.’

Ragen looked closely at Selia, perhaps trying to tell if she was joking, but her stony face gave no indication. He bowed again.

‘Hurry along, then,’ Selia said. ‘Lift your feet and you’ll both be back as everyone is readying to leave here for the night. If you and your Jongleur don’t want to pay Rusco for a room, any here will be glad to offer their homes.’ She shooed the two of them away and turned back to scold those pausing in their work to stare at the newcomers.

‘Is she always so … forceful?’ Ragen asked Arlen as they walked over to where the Jongleur was mumming for the youngest children. The rest had been pulled back to work.

Arlen snorted. ‘You should hear her talk to the greybeards. You’re lucky to get away with your skin after calling her “Barren”.’

‘Graig said that’s what everyone called her,’ Ragen said.

‘They do,’ Arlen agreed, ‘just not to her face, unless they’re looking to take a coreling by the horns. Everyone hops when Selia speaks.’

Ragen chuckled. ‘And her an old Daughter, at that,’ he mused. ‘Where I come from, only Mothers expect everyone to jump at their command like that.’

‘What difference does that make?’ Arlen asked.

Ragen shrugged. ‘Don’t know, I suppose,’ he conceded. ‘That’s just how things are in Miln. People make the world go, and Mothers make people, so they lead the dance.’

‘It’s not like that here,’ Arlen said.

‘It never is, in the small towns,’ Ragen said. ‘Not enough people to spare. But the Free Cities are different. Apart from Miln, none of the others give their women much voice at all.’

‘That sounds just as dumb,’ Arlen muttered.

‘It is,’ Ragen agreed.

The Messenger stopped, and handed Arlen the reins to his courser. ‘Wait here a minute,’ he said, and headed over to the Jongleur. The two men moved aside to talk, and Arlen saw the Jongleur’s face change again, becoming angry, then petulant, and finally resigned as he tried to argue with Ragen, whose face remained stony throughout.

Never taking his glare off the Jongleur, the Messenger beckoned with a hand to Arlen, who brought the horse over to them.

‘… don’t care how tired you are,’ Ragen was saying, his voice a harsh whisper, ‘these people have grisly work to do, and if you need to dance and juggle all afternoon to keep their kids occupied while they do it, then you’d damn well better! Now put your face back on and get to it!’ He grabbed the reins from Arlen and thrust them at the man.

Arlen got a good look at the young Jongleur’s face, full of indignation and fear, before the Jongleur took notice of him. The second he saw he was being watched, the man’s face rippled, and a moment later he was the bright, cheerful fellow who danced for children.

Ragen took Arlen to the cart and the two climbed on. Ragen snapped the reins, and they turned back up the dirt path that led to the main road.

‘What were you arguing about?’ Arlen asked as the cart bounced along.

The Messenger looked at him a moment, then shrugged. ‘It’s Keerin’s first time so far out of the city,’ he said. ‘He was brave enough when there was a group of us and he had a covered wagon to sleep in, but when we left the rest of our caravan behind in Angiers, he didn’t do near as well. He’s got day-jitters from the corelings, and it’s made him poor company.’

‘You can’t tell,’ Arlen said, looking back at the cartwheeling man.

‘Jongleurs have their mummers’ tricks,’ Ragen said. ‘They can pretend so hard to be something they’re not that they actually convince themselves of it for a time. Keerin pretended to be brave. The guild tested him for travel and he passed, but you never really know how people will hold up after two weeks on the open road until they do it for real.’

‘How do you stay out on the roads at night?’ Arlen asked. ‘Da says drawing wards in the soil’s asking for trouble.’

‘Your da is right,’ Ragen said. ‘Look in that compartment by your feet.’

Arlen did, and produced a large bag of soft leather. Inside was a knotted rope, strung with lacquered wooden plates bigger than his hand. His eyes widened when he saw wards carved and painted into the wood.

Immediately, Arlen knew what it was: a portable warding circle, large enough to surround the cart and more besides. ‘I’ve never seen anything like it,’ Arlen said.

‘They’re not easy to make,’ the Messenger said. ‘Most Messengers spend their whole apprenticeship mastering the art. No wind or rain is going to smudge those wards. But even then, they’re not the same as having warded walls and a door.

‘Ever see a coreling face-to-face, boy?’ he asked, turning and looking at Arlen hard. ‘Watched it take a swipe at you with nowhere to run and nothing to protect you except magic you can’t see?’ He shook his head. ‘Maybe I’m being too hard on Keerin. He handled his test all right. Screamed a bit, but that’s to be expected. Night after night is another matter. Takes its toll on some men, always worried that a stray leaf will land on a ward, and then …’ He hissed suddenly and swiped a clawed hand at Arlen, laughing when the boy jumped.

Arlen ran his thumb over each smooth, lacquered ward, feeling their strength. There was one of the little plates for every foot of rope, much as there would be in any warding. He counted more than forty of them. ‘Can’t wind demons fly into a circle this big?’ he asked. ‘Da puts posts up to keep them from landing in the fields.’

The man looked over at him, a little surprised. ‘Your da’s probably wasting his time,’ he said. ‘Wind demons are strong fliers, but they need running space or something to climb and leap from in order to take off. Not much of either in a cornfield, so they’d be reluctant to land, unless they saw something too tempting to resist, like some little boy sleeping in the field on a dare.’ He looked at Arlen in that same way Jeph did, when warning Arlen that the corelings were serious business. As if he didn’t know.

‘Wind demons also need to turn in wide arcs,’ Ragen continued, ‘and most of them have a wingspan larger than that circle. It’s possible that one could get in, but I’ve never seen it happen. If it does, though …’ He gestured to the long, thick spear he kept next to him.

‘You can kill a coreling with a spear?’ Arlen asked.

‘Probably not,’ Ragen replied, ‘but I’ve heard that you can stun them by pinning them against your wards.’ He chuckled. ‘I hope I never have to find out.’

Arlen looked at him, wide-eyed.

Ragen looked back at him, his face suddenly serious. ‘Messengering’s dangerous work, boy,’ he said.

Arlen stared at him a long time. ‘It would be worth it, to see the Free Cities,’ he said at last. ‘Tell me true, what’s Fort Miln like?’

‘It’s the richest and most beautiful city in the world,’ Ragen replied, lifting his mail sleeve to reveal a tattoo on his forearm of a city nestled between two mountains. ‘The Duke’s Mines run rich with salt, metal, and coal. Its walls and rooftops are so well warded, it’s rare for the house wards to even be tested. When the sun shines on its walls, it puts the mountains themselves to shame.’

‘Never seen a mountain,’ Arlen said, marvelling as he traced the tattoo with a finger. ‘My da says they’re just big hills.’

‘You see that hill?’ Ragen asked, pointing north of the road.

Arlen nodded. ‘Boggin’s Hill. You can see the whole Brook from up there.’

Ragen nodded. ‘You know what a “hundred” means, Arlen?’ he asked.

Arlen nodded again. ‘Ten pairs of hands.’

‘Well even a small mountain is bigger than a hundred of your Boggin’s Hills piled on top of each other, and the mountains of Miln are not small.’

Arlen’s eyes widened as he tried to contemplate such a height. ‘They must touch the sky,’ he said.

‘Some are above it,’ Ragen bragged. ‘Atop them, you can look down at the clouds.’

‘I want to see that one day,’ Arlen said.

‘You could join the Messengers’ guild, when you’re old enough,’ Ragen said.

Arlen shook his head. ‘Da says the people that leave are deserters,’ he said. ‘He spits when he says it.’

‘Your da doesn’t know what he’s talking about,’ Ragen said. ‘Spitting doesn’t make things so. Without Messengers, even the Free Cities would crumble.’

‘I thought the Free Cities were safe?’ Arlen asked.

‘Nowhere is safe, Arlen. Not truly. Miln has more people and can absorb the deaths more easily than a place like Tibbet’s Brook, but the corelings still take a toll each year.’

‘How many people are in Miln?’ Arlen asked. ‘We have nine hundreds in Tibbet’s Brook, and Sunny Pasture up the ways is supposed to be almost as big.’

‘We have over thirty thousands in Miln,’ Ragen said proudly.

Arlen looked at him, confused.

‘A thousand is ten hundreds,’ the Messenger supplied.

Arlen thought a moment, then shook his head. ‘There ent that many people in the world,’ he said.

‘There are and more,’ Ragen said. ‘There’s a wide world out there, for those willing to brave the dark.’

Arlen didn’t answer, and they rode in silence for a time.

It took about an hour and a half for the trundling cart to reach Town Square. The centre of the Brook, Town Square held just over two dozen warded wooden houses for those whose trade did not have them working in the fields or rice paddies, fishing, or cutting wood. It was here one came to find the tailor and the baker, the farrier, the cooper, and the rest.

At the centre lay the square where people would gather, and the biggest building in the Brook, the general store. It had a large open front room that housed tables and the bar, an even larger storeroom in back, and a cellar below, filled with almost everything of value in the Brook.

Hog’s daughters, Dasy and Catrin, ran the kitchen. Two credits could buy a meal to leave you stuffed, but Silvy called old Hog a cheat, since two credits could buy enough raw grain for a week. Still, plenty of unmarried men paid the price, and not all for the food. Dasy was homely and Catrin fat, but Uncle Cholie said the men who married them would be set for life.

Everyone in the Brook brought Hog their goods, be it corn or meat or fur, pottery or cloth, furniture or tools. Hog took the items, counted them up, and gave the customers credits to buy other things at the store.

Things always seemed to cost a lot more than Hog paid for them, though. Arlen knew enough numbers to see that. There were some famous arguments when people came to sell, but Hog set the prices, and usually got his way. Just about everyone hated Hog, but they needed him all the same, and were more likely to brush his coat and open his doors than spit when he passed.

Everyone else in the Brook worked throughout the sun, and barely saw all their needs met, but Hog and his daughters always had fleshy cheeks, rounded bellies, and clean new clothes. Arlen had to wrap himself in a rug whenever his mother took his overalls to wash.

Ragen and Arlen tied off the mules in front of the store and went inside. The bar was empty. Usually the air inside the taproom was thick with bacon fat, but there was no smell of cooking from the kitchen today.

Arlen rushed ahead of the Messenger to the bar. Rusco had a small bronze bell there, brought with him when he came from the Free Cities. Arlen loved that bell. He slapped his hand down on it and grinned at the clear sound.

There was a thump in the back, and Rusco came through the curtains behind the bar. He was a big man, still strong and straight-backed at sixty, but a soft gut hung around his middle, and his iron-grey hair was creeping back from his lined forehead. He wore light trousers and leather shoes with a clean white cotton shirt, the sleeves rolled halfway up his thick forearms. His white apron was spotless, as always.

‘Arlen Bales,’ he said with a patient smile, seeing the boy. ‘Did you come just to play with the bell, or do you have some business?’

‘The business is mine,’ Ragen said, stepping forward. ‘You Rusco Hog?’

‘Just Rusco will do,’ the man said. ‘The townies slapped the “Hog” on, though not to my face. Can’t stand to see a man prosper.’

‘That’s twice,’ Ragen mused.

‘Say again?’ Rusco said.

‘Twice that Graig’s journey log has led me astray,’ Ragen said. ‘I called Selia “Barren” to her face this morning.’

‘Ha!’ Rusco laughed. ‘Did you now? Well, that’s worth a drink on the house, if anything is. What did you say your name was?’

‘Ragen,’ the Messenger said, dropping his heavy satchel and taking a seat at the bar. Rusco tapped a keg, and plucked a slatted wooden mug off a hook.

The ale was thick and honey-coloured, and foamed to a white head on top of the mug. Rusco filled one for Ragen and another for himself. Then he glanced at Arlen, and filled a smaller cup. ‘Take that to a table and let your elders talk at the bar,’ he said. ‘And if you know what’s good for you, you won’t tell your mum I gave it to you.’

Arlen beamed, and ran off with his prize before Rusco had a chance to reconsider. He had sneaked a taste of ale from his father’s mug at festivals, but had never had a cup of his own.

‘I was starting to worry no one was coming ever again,’ he heard Rusco tell Ragen.

‘Graig took a chill just before he was to leave last fall,’ Ragen said, drinking deeply. ‘His Herb Gatherer told him to put the trip off until he got better, but then winter set in, and he got worse and worse. In the end, he asked me to take his route until the guild could find another. I had to take a caravan of salt to Angiers anyway, so I added an extra cart and swung this way before heading back north.’

Rusco took his mug and filled it again. ‘To Graig,’ he said, ‘a fine Messenger, and a dangerous haggler.’ Ragen nodded and the two men clapped mugs and drank.

‘Another?’ Rusco asked, when Ragen slammed his mug back down on the bar.

‘Graig wrote in his log that you were a dangerous haggler, too,’ Ragen said, ‘and that you’d try to get me drunk first.’

Rusco chuckled, and refilled the mug. ‘After the haggling, I’ll have no need to serve these on the house,’ he said, handing it to Ragen with a fresh head.

‘You will if you want your mail to reach Miln,’ Ragen said with a grin, accepting the mug.

‘I can see you’re going to be as tough as Graig ever was,’ Rusco grumbled, filling his own mug. ‘There,’ he said, when it foamed over, ‘we can both haggle drunk.’ They laughed, and clashed mugs again.

‘What news of the Free Cities?’ Rusco asked. ‘The Krasians still determined to destroy themselves?’

Ragen shrugged. ‘By all accounts. I stopped going to Krasia a few years ago, when I married. Too far, and too dangerous.’

‘So the fact that they cover their women in blankets has nothing to do with it?’ Rusco asked.

Ragen laughed. ‘Doesn’t help,’ he said, ‘but it’s mostly how they think all Northerners, even Messengers, are cowards for not spending our nights trying to get ourselves cored.’

‘Maybe they’d be less inclined to fight if they looked at their women more,’ Rusco mused. ‘How about Angiers and Miln? The dukes still bickering?’

‘As always,’ Ragen said. ‘Euchor needs Angiers’ wood to fuel his refineries, and grain to feed his people. Rhinebeck needs Miln’s metal and salt. They have to trade to survive, but instead of making it easy on themselves, they spend all their time trying to cheat each other, especially when a shipment is lost to corelings on the road. Last summer, demons hit a caravan of steel and salt. They killed the drivers, but left most of the cargo intact. Rhinebeck retrieved it, and refused to pay, claiming salvage rights.’

‘Duke Euchor must have been furious,’ Rusco said.

‘Livid,’ Ragen agreed. ‘I was the one that brought him the news. He went red in the face, and swore Angiers wouldn’t see another ounce of salt until Rhinebeck paid.’

‘Did Rhinebeck pay?’ Rusco asked, leaning in eagerly.

Ragen shook his head. ‘They did their best to starve each other for a few months, and then the Merchants’ guild paid, just to get their shipments out before the winter came and they rotted in storage. Rhinebeck is angry at them now, for giving in to Euchor, but his face was saved and the shipments were moving again, which is all that mattered to anyone other than those two dogs.’

‘Wise to watch what you call the dukes,’ Rusco warned, ‘even this far out.’

‘Who’s going to tell them?’ Ragen asked. ‘You? The boy?’ He gestured at Arlen. Both men laughed.

‘And now I have to bring Euchor news of Riverbridge, which will make things worse,’ Ragen said.

‘The town on the border of Miln,’ Rusco said, ‘barely a day out from Angiers. I have contacts there.’

‘Not anymore, you don’t,’ Ragen said pointedly, and the men were quiet for a time.

‘Enough bad news,’ Ragen said, hauling his satchel onto the bar. Rusco considered it dubiously.

‘That doesn’t look like salt,’ he said, ‘and I doubt I have that much mail.’

‘You have six letters, and an even dozen packages,’ Ragen said, handing Rusco a sheaf of folded paper. ‘It’s all listed here, along with all the other letters in the satchel and packages on the cart to be distributed. I gave Selia a copy of the list,’ he warned.

‘What do I want with that list, or your mailbag?’ Rusco asked.

‘The Speaker is occupied, and won’t be able to distribute the mail and read to those that can’t. She volunteered you.’

‘And how am I to be compensated for spending my business hours reading to the townies?’ Rusco asked.

‘The satisfaction of a good deed to your neighbours?’ Ragen asked.

Rusco snorted. ‘I didn’t come to Tibbet’s Brook to make friends,’ he said. ‘I’m a businessman, and I do a lot for this town.’

‘Do you?’ Ragen asked.

‘Damn right,’ Rusco said. ‘Before I came to this town, all they did was barter.’ He made the word a curse, and spat on the floor. ‘They collected the fruits of their labour and gathered in the square every Seventhday, arguing over how many beans were worth an ear of corn, or how much rice you had to give the cooper to make you a barrel to put your rice in. And if you didn’t get what you needed on Seventhday, you had to wait until the next week, or go door to door. Now everyone can come here, any day, any time from sunup to sundown, and trade for credits to get whatever else they need.’

‘The town saviour,’ Ragen said wryly. ‘And you asking nothing in return.’

‘Nothing but a tidy profit,’ Rusco said with a grin.

‘And how often do the villagers try to string you up for a cheat?’ Ragen asked.

Rusco’s eyes narrowed. ‘Too often, considering half of them can’t count past their fingers, and the other half can only add their toes to that,’ he said.

‘Selia said the next time it happens, you’re on your own,’ Ragen’s friendly voice had suddenly gone hard, ‘unless you do your part. There’s plenty on the far side of town suffering worse than having to read the mail.’

Rusco frowned, but he took the list and carried the heavy bag into his storeroom.

‘How bad is it, really?’ he asked when he returned.

‘Bad,’ Ragen said. ‘Twenty-seven so far, and a few still unaccounted for.’

‘Creator,’ Rusco swore, drawing a ward in the air in front of him. ‘I had thought a family, at worst.’

‘If only,’ Ragen said.

They were both silent for a moment, as was decent, then looked up at each other as one.

‘You have this year’s salt?’ Rusco asked.

‘You have the Duke’s rice?’ Ragen replied.

‘Been holding it all winter, you being so late,’ Rusco said.

Ragen’s eyes narrowed.

‘Oh, it’s still good!’ Rusco said, his hands coming up suddenly, as if pleading. ‘I’ve kept it sealed and dry, and there are no vermin in my cellar!’

‘I’ll need to be sure, you understand,’ Ragen said.

‘Of course, of course,’ Rusco said. ‘Arlen, fetch that lamp!’ he ordered, pointing the boy towards the corner of the bar.

Arlen scurried over to the lantern, picking up the striker. He lit the wick and lowered the glass reverently. He had never been trusted to hold glass before. It was colder than he imagined, but quickly grew warm as the flame licked it.

‘Carry it down to the cellar for us,’ Rusco ordered. Arlen tried to contain his excitement. He had always wanted to see behind the bar. They said if everyone in the Brook put all their possessions in one pile, it would not rival the wonders of Hog’s cellar.

He watched as Rusco pulled a ring on his floor, opening a wide trap. Arlen came forward quickly, worried old Hog would change his mind. He went down the creaking steps, holding the lantern high to illuminate the way. As he did, the light touched on stacks of crates and barrels from floor to ceiling, running in even rows stretching back past the edges of the light. The floor was wooden to prevent corelings from rising directly into the cellar from the Core, but there were still wards carved into the racks along the walls. Old Hog was careful with his treasures.

The storekeeper led the way through the aisles to the sealed barrels in the back. ‘They look unspoiled,’ Ragen said, inspecting the wood. He considered a moment, then chose at random. ‘That one,’ he said, pointing to a barrel.

Rusco grunted and hauled out the barrel in question. Some people called his work easy, but his arms were as hard and thick as any that swung an axe or scythe. He broke the seal and popped the top off the barrel, scooping rice into a shallow pan for Ragen to inspect.

‘Good Marsh rice,’ he told the Messenger, ‘and not a weevil to be seen, nor sign of rot. This will fetch a high price in Miln, especially after so long.’ Ragen grunted and nodded, so the cask was resealed and they returned upstairs.

They argued for some time over how many barrels of rice the heavy sacks of salt on the cart were worth. In the end, neither of them seemed happy, but they shook hands on the deal.

Rusco called his daughters, and they all went out to the cart to begin unloading the salt. Arlen tried lifting a bag, but it was far too heavy, and he staggered and fell, dropping it.

‘Be careful!’ Dasy scolded, slapping the back of his head.

‘If you can’t lift, then get the door!’ Catrin barked. She herself had one sack over her shoulder and another tucked under her meaty arm. Arlen scrambled to his feet and rushed to hold the portal for her.

‘Fetch Ferd Miller and tell him we’ll pay five … make it four credits for every sack he grinds,’ Rusco told Arlen. Most everyone in the Brook worked for Hog, one way or another, but the Squarefolk most of all. ‘Five if he packs it in barrels with rice to keep it dry.’

‘Ferd is off in the Cluster,’ Arlen said. ‘Most everyone is.’

Rusco grunted, but did not reply. Soon enough the cart was empty, save for a few boxes and sacks that did not contain salt. Rusco’s daughters eyed those hungrily, but said nothing.