Полная версия

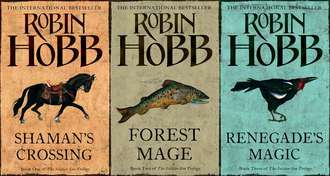

The Complete Soldier Son Trilogy: Shaman’s Crossing, Forest Mage, Renegade’s Magic

Kort replied with an obscenity that I’d never heard him use before. Natred chuckled bitterly. Those two had seemed almost immune from the tension; I now realized that they were just as anxious as the rest of us. I heard Spink sit up without a word. He sighed heavily and made his way through the dark to our lamp. He lit it. The yellow light made him look jaundiced. Despite his longer sleep, he still had dark circles under his eyes. He scratched at his cheek, and then went to the washstand to peer blearily at himself. ‘It would almost be a relief to fail,’ he said quietly. ‘To be sent home and to know that it had all fallen to pieces and that no one would have any expectations of me any more.’

‘And take us all down with you?’ Natred asked, outraged.

‘Of course not. That would haunt me to the end of my days. And that is why I’ve studied so hard, and I won’t fail. Not today. I won’t fail.’

But even to me, he sounded more determined than convincing.

The room was colder and the lamp seemed dimmer than usual as we dressed. While waiting my turn for the washbasin, I went to the window and looked out. The Academy grounds were cold and still. The sky was still black overhead, with the last stars fading. The day would be clear, then. Clear and cold. A shallow crust of snow, trampled in places, caked the lawns and tree branches. I looked at the reaching black branches of the tree and a vague memory stirred. When I tried to recall it, the bits fled. I shook my head, at myself and at the Academy grounds before me. They looked the most dismal place in the world. It was strange, but the snow appeared abused and out of place in that city world. If I had wakened to a similar morning in the open countryside it would have felt like a crisp, clean winter day. In Old Thares, it felt like a mistake.

No one spoke much. There were mutters and grumbles of complaint, but I think each one of us was too caught up in his own fears to say much of anything to his fellows. We mustered in the usual place where Corporal Dent appeared to curse and blame us for his miserable life. I felt dull and discouraged and wondered briefly why I had ever wanted so desperately to be here. This was not the golden future I had imagined for myself. This was misery, pure and simple. I wondered if Spink had been right. Maybe it would just be a relief to be sent home, with all expectations of me vanished forever. I gave myself a shake, trying to dispel my gloominess. Dent gave me a demerit for moving in ranks. I scarcely noticed.

We waited in the cold and the dark until our cadet officers came by and reviewed us. Surprisingly, they found little to scorn us for that day. Perhaps they, too, dreaded the day’s exams, even though the upper classmen were immune from the culling process. Or perhaps they looked forward to Dark Evening’s holiday and felt merciful to us. Maybe it was simply too dark for Jaffers to see that I had not brushed my jacket and that my trousers had spent the night on the floor, not on a hanger. In any case, Cadet Captain Jaffers allowed how we appeared and we were dismissed from our inspection.

We marched off to a breakfast I had no stomach for. I forced myself to eat, reminding myself of Sergeant Duril’s saying, ‘The soldier who doesn’t break his fast when he can is a fool.’ At the table, only Gord seemed to eat with a will. Spink pecked at his food. Trist heaped his plate, ate five bites and then pushed at the rest as if he were poking a dead animal with a stick. Ordinarily, Corporal Dent would have demanded that he eat whatever he took, and lectured us all that a man who took supplies greedily and then wasted them was a liability to his whole regiment. Dent, however, had found as many possible excuses as he could of late to leave us alone at table, so there was no one to rebuke us for the half-eaten meals that day.

We fell in and marched off through a cold day that was just now turning grey to our first class. In Military History the entire chalkboard was already covered in questions written out in Captain Infal’s sloping hand. He greeted us with, ‘Come in, leave your books closed, and start writing. I will collect your papers at the end of class. No talking until then.’

And that was it. I set out my paper and began writing. I tried to pace myself, to be sure that I would write at least some sort of answer to each question and did well enough at that. I left space at the ends of some answers to allow myself to add more detail if I had time. I struggled with dates and with the sequences of the sea battles. I wrote until my pen was slick in my fingers and my hand ached. And suddenly Captain Infal was announcing, ‘That’s it, Cadets. Finish the sentence you are writing and put your pens away. Leave your papers on your desk. I will take them up. Dismissed.’

And that was it. The day outside had warmed a bit, but not enough to melt the ice on the walkways. The closer we got to the river, the more bitterly the wind blew. The dilapidated maths and science building creaked in the cold. There were coal stoves in each classroom, but their warmth did not seem to extend more than a few feet beyond their sullen iron bellies. We took our customary places, with Gord sitting on one side of Spink and me on the other. Captain Rusk saw us seated, then went to the board and began writing the first problem. ‘Begin as you are ready,’ he instructed us. I gave Spink a reassuring smile but I don’t think he saw it. His nose was red with cold, and the rest of his face white with weariness and perhaps fear.

I recognized Rusk’s first problem as one directly out of the textbook examples. I could have simply written the answer, but he demanded that all work be shown. I worked steadily, taking down each problem as he wrote it, and several times blessed my father for seeing me so well prepared for my first year of Academy.

Midway through the test, it happened. I heard a small crunch, and then Gord’s hand shot immediately into the air. Rusk sighed. ‘Yes, Cadet?’

‘I’ve broken my pencil, sir. May I ask to borrow one?’

Rusk sighed. ‘A prepared soldier would have an extra one with him. You cannot always depend on your comrades, though you should always be in a position to let them depend on you. Has anyone an extra pencil that Cadet Lading may use?’

Spink lifted his hand. ‘I do, sir.’

‘Then lend it, Cadet. Please continue with your tests.’

Gord leaned over to accept the pencil that Spink offered. As he did so, his desk bumped against his sizeable midsection and then lurched against Spink’s. Both their papers cascaded to the floor under Spink’s desk. Spink leaned down, gathered the papers and handed Gord’s back to him, along with the extra pencil. I watched this from the corner of my eye. And I could not be certain that Spink gave Gord back every sheet that truly belonged to him.

Captain Rusk made no comment on it. He continued his slow pace around the room. I heard my classmates groan when he announced, ‘You should have finished with these problems by now,’ and erased the first set on the board. He immediately began to write more problems. And I sat there, feeling paralysed and sick, not by the maths, which was well within my abilities, but by my uncertainty. Had they cheated? Had they planned that manoeuvre? Did I have an honour duty to raise my hand and inform Captain Rusk that they possibly had cheated? But what if they hadn’t? What if it was coincidence? I would have doomed the nine men of my patrol to expulsion from the Academy. We would all be culled, because I had had a suspicion. I felt a sudden wave of loathing for Trist, so busily scratching away at his own paper. But for his horrid suggestion, I would never have considered Gord or Spink capable of cheating. I could not move until Captain Rusk asked me, ‘Cadet Burvelle? Finished already?’

His words jolted me back to my own situation, and I immediately replied, ‘No, sir,’ and bent my head over my own paper and my mind back to the task before me. Despite my delay, which had seemed an eternity but had likely been only a minute or two, I finished well within the hour and had time to go back and check my work. I found several errors, probably due to my rattled state. Nonetheless, when Captain Rusk announced, ‘Time! Pass your papers to the cadet on your right. End cadets, bring the papers forward to me,’ I felt as queasy as if I had failed every problem.

I kept my eyes to myself and spoke not a word as we left our classroom and formed up for our march across campus. A few of the others whispered to one another about two of the knottier problems on the test, but both Spink and Gord were as silent as I was. Despite the cold air, I felt sweat trickle down my back.

My test in Varnian is a hazy memory to me. We were given a technical passage from a cavalla strategy text to translate into Gernian, and then had to compose an essay in Varnian about how to care for a horse. I handed in my papers feeling I had done well enough. The trick of the essay was, of course, to keep to vocabulary and verb forms one was certain of.

Our mid-day meal was next. We went first to Carneston House, to exchange our morning books and notes for our afternoon materials, and then straight to the mess hall. I didn’t speak a word to anyone. No one seemed to notice my silence. They were all preoccupied with the tests we had completed and dreading the ones still to come. If anyone else had noticed what had happened between Gord and Spink, they chose to keep as quiet about it as I did. The cooks had prepared a hot and hearty bean soup containing chunks of fat ham and plenty of fresh bread to go with it. It smelled good, much better than their usual concoctions, but I scarcely tasted it. Spink seemed lighter of spirit, as if he had faced his most feared demon and the rest of the day could not daunt him. I avoided meeting his eyes for fear of what I might read there. Would I know if my best friend had forsaken his honour and cheated on a test? And with the next breath, I traitorously wondered if that would be such a bad thing, if he had done it so that his fellows, including me, could continue at the Academy? Did the ends justify the means? Was the culling, as Trist had suggested, a cruel way to test our loyalty to one another as well as our learning? And then my mind came back to Rusk’s comment about Gord needing to borrow a pencil – that one cannot always depend on his comrades but should always be in a position to let them depend on oneself – and wondered if there had been some hidden meaning there.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.