Полная версия

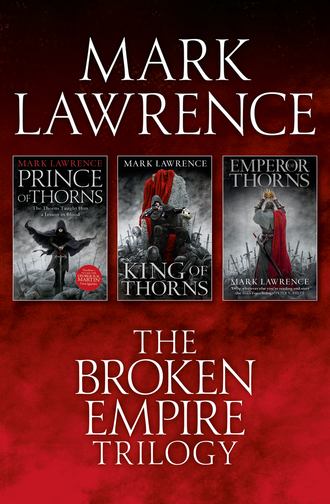

The Complete Broken Empire Trilogy: Prince of Thorns, King of Thorns, Emperor of Thorns

‘A bog-town, my prince. A nothing. A place where they cut peat for the protectorate. Seventeen huts and perhaps a few more pigs.’ He tried a laugh, but it came out too sharp and nervy.

‘So you journeyed there to offer absolution to the poor?’ I held his eye.

‘Well …’

‘Out past Hanton, out to the edge of the marsh, out into danger,’ I said. ‘You’re a very holy man, Father.’

He bowed his head at that.

Jessop. The name rang a bell. A bell with a deep voice, slow and solemn. Send not to ask for whom the bell tolls …

‘Jessop is where the marsh-tide takes the dead,’ I said. I saw the words on the mouth of old Tutor Lundist as I spoke them. I saw the map behind him, pinned to the study wall, currents marked in black ink. ‘It’s a slow current but sure. The marsh keeps her secrets, but not forever, and Jessop is where she tells them.’

‘That big man, Rike, he’s strangling the fat one.’ Father Gomst nodded toward the town.

‘My father sent you to look at the dead.’ I didn’t let Gomst divert me with small talk. ‘Because you’d recognize me.’

Gomst’s mouth framed a ‘no’, but every other muscle in him said ‘yes’. You’d think priests would be better liars, what with their job and all.

‘He’s still looking for me? After four years!’ Four weeks would have surprised me.

Gomst edged back in his saddle. He spread his hands helplessly. ‘The Queen is heavy with child. Sageous tells the King it will be a boy. I had to confirm the succession.’

Ah! The ‘succession’. That sounded more like the father I knew. And the Queen? Now that put an edge on the day.

‘Sageous?’ I asked.

‘A heathen bone-picker, newly come to court.’ Gomst spat the words as if they tasted sour.

The pause grew into a silence.

‘Rike!’ I said. Not a shout, but loud enough to reach him. ‘Put Fat Burlow down, or I’ll have to kill you.’

Rike let go, and Burlow hit the ground like the three hundred pound lump of lard that he was. I guess that of the two, Burlow looked slightly more purple in the face, but only a little. Rike came toward us with his hands out before him, twisting as though he already had them around my neck. ‘You!’

No sign of Makin, and Father Gomst would be as useful as a fart in the wind against Little Rikey with a rage on him.

‘You! Where’s the fecking gold you promised us?’ A score of heads popped out of windows and doors at that. Even Fat Burlow looked up, sucking in a breath as if it came through a straw.

I let my hand slip from the pommel of my sword. It doesn’t do to sacrifice too many pawns. Rike had only a dozen yards to go. I swung off Gerrod’s saddle and patted his nose, my back to the town.

‘There’s more than one kind of gold in Norwood,’ I said. Loud enough but not too loud. Then I turned and walked past Rike. I didn’t look at him. Give a man like Rike a moment, and he’ll take it.

‘Don’t you be telling me about no farmers’ daughters this time, you little bastard!’ He followed me roaring, but I’d let the heat out of him. He just had wind and noise now. ‘That fecker of a count staked them all out to burn already.’

I made for Midway Street, leading up to the burgermeister’s house from the market field. As we passed him, Brother Gains looked up from the cook-fire he’d started. He clambered to his feet to follow and watch the fun.

The grain-store tower had never looked like much. It looked less impressive now, all scorched, the stones split in the heat. Before they burned them all away, the grain sacks would have hidden the trapdoor. I found it with a little prodding. Rike huffed and puffed behind me all the time.

‘Open it up.’ I pointed to the ring set in the stone slab.

Rike didn’t need telling twice. He got down and heaved the slab up as if it weighed nothing. And there they were, barrel after barrel, all huddled up in the dusty dark.

‘The old burgermeister kept the festival beer under the grain-tower. Every local knows that. A little stream runs down there to keep it all nice and cool-like. Looks like, what, twenty? Twenty barrels of golden festival beer.’ I smiled.

Rike didn’t smile back. He stayed on his hands and knees, and let his eye wander up the blade of my sword. I imagined how it must tickle against his throat.

‘See now, Jorg, Brother Jorg, I didn’t mean …’ he started. Even with my sword at his neck he had a mean look to him.

Makin clattered up and came to stand at my shoulder. I kept the blade at Rike’s throat.

‘I may be little, Little Rikey, but I ain’t a bastard,’ I said, soft, in my killing voice. ‘Isn’t that right, Father Gomst? If I was a bastard you wouldn’t have to risk life and limb to search the dead for me, now would you?’

‘Prince Jorg, let Captain Bortha kill this savage.’ Gomst must have found his composure somewhere. ‘We’ll ride on to the Tall Castle and your father—’

‘My father can damn well wait!’ I shouted. I bit back the rest, angry at being angry.

Rike forgot about the sword for a moment. ‘What the feck is all this “prince” shit? What the feck is all this “Captain Bortha” shit? And when do I get to drink the fecking beer?’

We had ourselves as full an audience then as we’d get, all the brothers about us in a circle.

‘Well,’ I said. ‘Since you ask so nice, Brother Rike, I’ll tell you.’

Makin raised his brows at me and he took a grip on his sword. I waved him down.

‘The Captain Bortha shit is Makin being Captain Makin Bortha of the Ancrath Imperial Guard. The prince shit is me being the beloved son and heir of King Olidan of the House of Ancrath. And we can drink the beer now, because today is my fourteenth birthday, and how else would you toast my health?’

Every brotherhood has a pecking order. With brothers like mine you don’t want to be at the bottom of that order. You’re liable to get pecked to death. Brother Jobe had just the right mix of whipped cur and rabies to stay alive there.

8

So we sat on the tumbled stones of the burgermeister’s house and drank beer. The brothers drank deep and called out my name. Some had it ‘Brother Jorg’, some had it ‘Prince Jorg’, but all of them saw me with new eyes. Rike watched me, beer-foam in his stubbled beard, the line of my sword across his neck. I could see him weighing the odds, a slow ballet of possibilities working their way across his low forehead. I didn’t wait for the word ‘ransom’ to bubble to the surface.

‘He wants me dead, Little Rikey,’ I said. ‘He sent Gomsty out to find proof I was dead, not to find me. He’s got a new queen now.’

Rike gave a grin that had more scowl than grin in it, then belched mightily. ‘You ran from a castle with gold and women, to ride with us? What idiot would do that?’

I sipped my beer. It tasted sour, but that seemed right somehow. ‘An idiot who knows he won’t win the war with the King’s guard at his side,’ I said.

‘What war, Jorg?’ The Nuban sat close by, not drinking. He always spoke slow and serious. ‘You want to beat the Count? Baron Kennick?’

‘The War,’ I said. ‘All of it.’

Red Kent came over from the barrels, his helm brimming with ale. ‘Never happen,’ he said. He lifted the helm and half-drained it in four swallows. ‘So you’re Prince of Ancrath? A copper-crown kingdom. Must be dozens with as good a claim on the high throne. Each of them with their own army.’

‘More like fifty,’ Rike growled.

‘Closer to a hundred,’ I said. ‘I’ve counted.’

A hundred fragments of empire grinding away at each other in a never-ending cycle of little wars, feuds, skirmishes, kingdoms waxing, waning, waxing again, lifetimes spent in conflict and nothing changing. Mine to change, to end, to win.

I finished my beer and got up to find Makin.

I didn’t have to look far. I found him with the horses, checking his stallion, Firejump.

‘What did you find?’ I asked him.

Makin pursed his lips. ‘I found the pyre. About two hundred, all dead. They didn’t light it though – probably scared off.’ He waved toward the west. ‘They came in on foot, up the marsh road, and over the ridge yonder. Had about twenty archers in the thicket by the stream, to pick off folks that tried to run.’

‘How many men altogether?’ I asked.

‘Probably a hundred. Foot soldiers most of them.’ He yawned and ran a hand from forehead to chin. ‘Two days gone now. We’re safe enough.’

I felt invisible thorns scratching at me, sharp hooks in my skin. ‘Come with me,’ I told him.

Makin followed me back to the steps and fallen pillars at the burgermeister’s doors. The brothers had Maical staving in a second barrel.

‘What ho, Captain!’ Burlow called out at Makin, his voice still hoarse from Rike’s strangling. A laugh went up at that, and I let it run its course. I felt the thorns again, sharp and deep. Sharpening me up for something. Two hundred bodies in a heap. All dead.

‘Cap’n Makin tells me we’re going to have company,’ I said.

Makin’s brows rose at that but I ignored him. ‘Twenty swords, rough men, bandits of the lowest order. Not the sort you’d like to meet,’ I told them. ‘Idling along in our direction, weighed down with loot.’

Rike got to his feet all sudden like, his flail rattling at his hip. ‘Loot?’

‘Slugs, I tell you. Growing rich off the destruction of others.’ I showed them my smile. ‘Well, my brothers, we’re going to have to show them the error of their ways. I want them dead. Every last one. And we’ll do it without a scratch. I want trip-pits in the main street. I want brothers hidden in the grain-tower and the Blue Boar tavern. I want Kent, Row, Liar and the Nuban here, behind these walls to shoot them down when they come between tower and tavern.’

The Nuban hefted his crossbow, a monstrous feat of engineering, worked in the old metal and embellished with the faces of strange gods. Kent tossed the dregs from his helm and set it on his head, ready with his longbow.

‘Now they might come over the ridge instead, so Rike’s going to take Maical and six others to hide in the tannery ruins. Anyone comes that way, let them past you, then gut them. Makin will be our scout to give us warning. The good father here and you five there, you’re going to stand with me to tempt them in.’

The brothers needed no telling. Well, Jobe did, but Rike hauled him out of the beer quick enough and he wasn’t gentle about it.

‘Loot!’ Rike shouted the words in his face. ‘Get digging trip-pits, shit-brains.’

They knew how to set up an ambush those lads. No mistake there. No one knew better how to fight in the ruins. Half the time they’d make the ruins themselves, half the time they’d fight in somebody else’s.

‘Burlow, Makin,’ I called them to me as the others set about their tasks. ‘I don’t need you to scout, Makin,’ I said, keeping my voice low. ‘I want you two to go to the thicket by the stream. I want you to hide yourselves. Hide so a bastard could sit on you and still not know you were there. You hide down there and wait. You’ll know what to do.’

‘Prince— Brother Jorg,’ Makin said. He had a big frown on, and his eyes kept straying down the street to old Gomsty praying before the burned-out church. ‘What’s this all about?’

‘You said you’d follow wherever I led, Makin,’ I answered. ‘This is where it starts. When they write the legend, this will be the first page. Some old monk will go blind illuminating this page, Makin. This is where it all starts.’ I didn’t say how short the book might be though.

Makin did that bow of his that’s half a nod, and off he went, Fat Burlow hurrying behind.

So, the brothers dug their traps, laid out their arrows, and hid themselves in what little of Norwood remained. I watched them, cursing their slowness, but holding my peace. And by and by only Father Gomst, my five picked men, and I remained on show. All the rest, a touch over two dozen, lay lost in the ruins.

Father Gomst came to my side, still praying. I wondered how hard he’d pray if he knew what was really coming.

I had an ache in my head now, like a hook inserted behind both eyes, tugging at me. The same ache that started up when the sight of old Gomsty made me think of going home. A familiar pain, one I’d felt at many a turn on the road. Oft times I’d let that pain lead me. But I felt tired of being a fish on a line. I bit back.

I saw the first scout on the marsh road an hour later. Others came soon enough, riding up to join him. I made sure they’d seen the seven of us standing on the burgermeister’s steps.

‘Company,’ I said, and pointed the riders out.

‘Shitdarn!’ Brother Elban spat on his boots. I’d chosen Elban because he didn’t look like much, a grizzled old streak in his rusty chainmail. He had no hair and no teeth, but he had a bite on him. ‘They’s no brigands, look at them ponies.’ He lisped the words a bit, having no teeth and all.

‘You know Elban, you might be right,’ I said, and I gave him a smile. ‘I’d say they looked more like house-troops.’

‘Lord have mercy,’ I heard old Gomsty murmur behind me.

The scouts pulled back. Elban picked up his gear and started for the market field where the horses stood grazing.

‘You don’t want to do that, old man,’ I said, softly.

He turned and I could see the fear in his eyes. ‘You ain’t gonna cut me down is you, Jorth?’ He couldn’t say Jorg without any teeth; I suppose it’s a name you’ve got to put an edge on.

‘I won’t cut you down,’ I said. I almost liked Elban; I wouldn’t kill him without a good reason. ‘Where you going to run to, Elban?’

He pointed over the ridge. ‘That’s the only clear way. Get snarled up elsewise, or worse, back in the marsh.’

‘You don’t want to go over that ridge, Elban,’ I said. ‘Trust me.’

And he did. Though maybe he trusted me because he didn’t trust me, if you get my meaning.

We stood and waited. We sighted the main column on the marsh road first, then moments later, the soldiers showed over the ridge. Two dozen of them, house-troops, carrying spears and shields, and above them the colours of Count Renar. The main column had maybe three score soldiers, and following on behind in a ragged line, well over a hundred prisoners, yoked neck to neck. Half a dozen carts brought up the rear. The covered ones would be loaded with provisions, the others held bodies, stacked like cord-wood.

‘House Renar doesn’t leave the dead unburned. They don’t take prisoners,’ I said.

‘I don’t understand,’ Father Gomst said. He’d gone past scared, into stupid.

I pointed to the trees. ‘Fuel. We’re on the edge of a swamp. There’s no trees for miles in this peat bog. They want a good blaze, so they’re bringing everyone back here to have a nice big bonfire.’

I had an explanation for Renar’s actions but as to my own, like Father Gomst, I wasn’t sure I understood either. Whatever strength I had on the road, it came to me through a willingness to sacrifice. It came on the day I set aside my vengeance on Count Renar as a thing without profit. And yet here I was, in the ruins of Norwood, with a thirst that couldn’t be quenched by any amount of festival beer. Waiting for that self-same count. Waiting with too few men, and with every instinct telling me to run. Every instinct, except for that one to hold or break, but never bend.

I could see individual figures at the head of the column quite clearly now. Six riders, chain-armoured, and a knight in heavy plate. The device on his shield came into view as he turned to signal his command. A black crow on a red field, a field of fire, Count Osson Renar wouldn’t lead a hundred men into an Ancrath protectorate, so this would be one of his boys. Marclos or Jarco.

‘The brothers won’t fight this lot,’ Elban said. He put a hand on my shoulder-plate. ‘We might fight a path out through the trees if we get to the horses, Jorth.’

Already twenty of the Renar men hastened toward the tree line, holding their longbows before them so they wouldn’t snag.

‘No.’ I let out a long sigh. ‘I’d best surrender.’

I held out my hand. ‘White flag if you please.’

The house-troops had deployed by the time I made my way down toward the main column. My ‘flag’ should properly be described as grey. An unwholesome grey at that, torn from Father Gomst’s hassock.

‘Noble born!’ I shouted. ‘Noble born under flag of truce!’

That surprised them. The house-troops, fanned out behind our horses, let me cross the market field unhindered. They looked to be a sorry lot, the metal scales falling from their leathers, rust on their swords. Homebodies they were, too long on the road and not hardened to it.

‘The lad wants to be first on the fire,’ one of them said. A skinny bastard with a boil on each cheek. He got a laugh with that.

‘Noble born!’ I called out. ‘Flag o’ truce.’ I didn’t expect to get this far with my sword.

I caught the stink of the column and could hear the weeping. The prisoners turned blank eyes upon me.

Two of Renar’s riders came forward to intercept me. ‘Where’d you steal the armour, boy?’

‘Go fuck yourself,’ I said. I kept it pleasant. ‘Who’ve you got leading this show then? Marclos?’

They exchanged a look at that. A wandering hedge-knight probably wouldn’t know one son of the House Renar from the next.

‘It doesn’t do to kill a noble prisoner without orders,’ I said. ‘Best let the Count-ling decide.’

Both riders dismounted. Tall men, veterans by the look of them. They took my sword. The older one, dark bearded with a white scar under both eyes, found my knife. The cut had taken the top of his nose too.

‘You’re a bit of an ugly mess aren’t you?’ I asked.

He found the knife in my boot as well.

I had no plan. The pain in my head hadn’t left any room for one. I’d ignored the wordless voice that had led me for so long. Ignored it for the joy of being stubborn. And here I was unarmed amongst too many foes, stupid and alone.

I wondered if my brother William was watching me. I hoped my mother wasn’t.

I wondered if I was going to die. If they’d burn me, or leave me as a maimed thing for Father Gomst to cart back to the Tall Castle.

‘Everyone has doubts,’ I said as Scar-face finished his search. ‘Even Jesu had his moment, and I ain’t him.’

The man looked at me as if I were mad. Maybe I was, but I’d found my peace. The pain left me and I saw things clear once again.

They led me to where Marclos sat on his horse, a monstrous stallion, twenty hands if it was one. He lifted his visor then and showed a pleasant face, a bit fat in the cheeks, quite jolly really. Looks, of course, can be deceiving.

‘Who the hell are you?’ he asked.

He had a nice bit of plate on, acid etched with a silver inlay and burnished so it shone even in the dreariest of light.

‘I said who the hell are you?’ He got some red in his cheeks then. Not so jolly. ‘You’ll sing on the fire, boy, so you may as well tell me now.’

I leaned forward as if to hear him. The bodyguards reached for me but I did the old shake and twist. Even with me in armour they were too slow. I used Marclos’s foot as a step, where it stuck out from the stirrup, and got up alongside him in no time at all. He had a nice stiletto in a sheath set handy in the saddle, so I had that out and stuck it in his eye. Then we were off. The pair of us galloping out across the market field. How to steal a horse is the first thing you learn on the road.

We bounced along, with him howling and shaking behind me. A couple of the house-troops tried to bar the way but I rode them down. They weren’t going to get up again either; that stallion was fearsome big. The archers might have taken a shot or three, but they couldn’t make sense of it from that distance, and we were headed into town.

I could hear the bodyguard thundering along behind. It sounded as if they knocked a few men down themselves. They came close, but we’d taken them by surprise, me and Marclos, and got a start on them. And as we reached the outskirts of Norwood they drew up short.

At the first building I wheeled sharply, and Marclos obliged by falling off. He hit the ground face first. Another one that wouldn’t be getting up again. It felt good, I won’t lie about that. I imagined the Count getting the news as he broke his fast. I wondered how he’d like the taste of it. Would he finish his eggs?

‘Men of Renar!’ I shouted it hard enough to hurt my lungs. ‘This town stands under the Prince of Ancrath’s protection. It will not be surrendered.’

I turned the horse again and rode on. A few arrows clattered behind me. At the steps I drew up and dismounted.

‘You came back …’ Father Gomst looked confused.

‘I did,’ I said. I turned to face Elban. ‘No fighting a retreat now eh, brother?’

‘You’re insane.’ The words escaped in a whisper. For some reason he didn’t lisp when he whispered.

The riders, Marclos’s personal guard, led the charge. Now that they had fifty foot soldiers around them, they had found their courage. Up on the ridge the two dozen house-troops took their cue and began to run with the slope. The archers started to emerge from the thicket for better aim.

‘These bastards will burn you alive if they take you that way,’ I said to the five brothers I had with me. Then I paused and I looked them in the eye, each one. ‘But they don’t want to die. They won’t want to go back to the Count either way. Would you take old bonfire-Renar his dead son back, and smooth it over with an “oh yes, but we killed scavengers … there was this boy … and an old man with no teeth …”?’

‘So mark me now. You fight these tame soldiers, and you show them hell. Show them enough of it and the bastards’ll break and run.’ I paused and caught Brother Roddat’s eye, for he was a weasel and like to run, sense or no sense. ‘You stick with me, Brother Roddat.’

I looked to the thicket, over the heads of the men surging up from the market field and saw an archer fall among the trees. Then another. An armoured figure emerged from the undergrowth. The archers in front of him still had their eyes on the advance. He took the head from the first one with a clean swing. Thank you, Makin, I thought. Fat Burlow came out at a run then, barrelling his armoured bulk into the bowmen.

The troops from the ridge passed by Rike’s position and his lads set to gutting them from behind. Not the sort of odds Little Rikey favoured, but the word ‘loot’ always did have an uncanny effect on him.

ChooOm! The Nuban’s crossbow shot its load. He couldn’t really miss with so many targets, but by rights he shouldn’t be able to pick his man with that thing. Even so, both bolts hit the lead rider in the chest and lifted him out of his saddle. Kent and the other two rose from behind the burgermeister’s walls. They did a double-take when they saw what was coming, but choices were in short supply and they had plenty of arrows.

The Renar troops hit our trip-pits at full tilt. I swear I heard the first ankle snap. After that it was all yelling as man went over man. Kent and Liar and Row took the opportunity to send a dozen more arrows into the main mass of the attack. The Nuban loaded his monster again and this time nearly took the head off a horse. The rider went over the top, and the beast fell onto him, brains spilling on the ground.

Some of those soldier boys didn’t like the road so much any more and took to finding a way through the ruins. Of course they found more than a way, they found the brothers who were waiting there.

The archers broke first. There isn’t much a man in a padded tunic, with a knife at his hip, can do against a decent swordsman in plate armour. And even Burlow was more than decent.

Three of the riders reached us. We didn’t stay on the street to meet them. We fell back into the skeleton of what used to be Decker’s Smithy. So they rode in, slowly, ash crunching under hoof. Elban leapt the first one from an alcove over the furnaces. Took that rider down sweet as sweet he did, his sharp little knife hitting home over and over. If you recall, I said Elban had a bite to him.