Полная версия

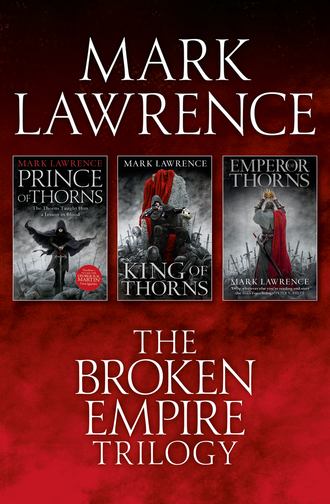

The Complete Broken Empire Trilogy: Prince of Thorns, King of Thorns, Emperor of Thorns

‘Very wise.’

‘The Grand Mêlée is more me. And the winner gets his prize from Count Renar himself!’

‘That’s not a plan. That’s a way to get a death so famously stupid that they’ll be laughing about it in alehouses for a hundred years to come,’ Makin said.

I started to clank back toward the road, leading Alain’s horse.

‘You’re right, Makin, but I’m running out of options here.’

‘We could hit the road again. Get a little gold together, get some more, enough to make lives somewhere they’ve never heard of Ancrath.’ I could see a longing in his eyes. Part of him really meant it.

I grinned. ‘I may be running out of options, but running out isn’t an option. Not for me.’

We rode toward The Haunt. Slowly. I didn’t want to visit the tourney field yet. We had no tent to pitch, and the Kennick colours would inevitably draw me deeper into the charade than my acting skills could support.

As we came out of the farmland into the sprawl of houses reaching from the castle walls, a hedge-knight caught up with us and pulled up.

‘Well met, sir …?’ He sounded out of breath.

‘Alain of Kennick,’ I supplied.

‘Kennick? I thought …’

‘We have an alliance now, Renar and Kennick are the best of friends these days.’

‘Good to hear. A man needs friends in times like these,’ the knight said. ‘Sir Keldon, by the way. I’m here for the lists. Count Renar places generous purses where a good lance can reach them.’

‘So I hear,’ I said.

Sir Keldon fell in beside us. ‘I’m pleased to be off the plains,’ he said. ‘They’re lousy with Ancrath scouts.’

‘Ancrath?’ Makin failed to keep the alarm from his voice.

‘You haven’t heard?’ Sir Keldon glanced back into the night. ‘They say King Olidan is massing his armies. Nobody’s sure where he’ll strike, but he’s sent the Forest Watch into action. Most of them are back there if I know anything!’ He stabbed a gauntleted finger over his shoulder. ‘And you know what that meant for Gelleth!’ He drew the finger across his throat.

We reached the crossroads at the town centre. Sir Keldon turned his horse to the left. ‘You’re to the Field?’

‘No, we’ve to pay our respects.’ I nodded toward The Haunt. ‘Good luck on the morrow.’

‘My thanks.’

We watched him go.

I turned Alain’s horse back toward the plains.

‘I thought we were going to pay our respects?’ Makin asked.

‘We are,’ I said.

I kicked my steed into a trot. ‘To Watch Master Coddin.’

45

I like mountains, always have done. Big obstinate bits of rock sticking up where they’re not wanted and getting in folk’s way. Great. Climbing them is a different matter altogether though. I hate that.

‘What in feck’s name was the point of stealing a horse if I have to drag the damn thing up the slightest incline we meet?’

‘To be fair, Prince, this is more by way of a cliff,’ Makin said.

‘I blame Sir Alain for owning a deficient horse. I should have kept the nag I came in on.’

Nothing but the labour of Makin’s breath.

‘I’m going to have to see Baron Kennick about that boy of his one day,’ I said.

At that point a stone turned under my foot and I fell in a clatter of what little armour I’d kept on.

‘Easy now, you’ve three bows on each of you.’ The voice came from further up the slope where the moonlight made little sense of the jumbled rock.

Makin straightened up slow and easy, leaving me to find my own way to my feet.

‘Sounds like a good Ancrath man to me,’ I said, loud enough for any on the slopes. ‘If you’re going to shoot anyone, might I suggest this horse here, he’s a better target and a lazy bastard to boot.’

‘Lay your swords down.’

‘We’ve only got one between us,’ I said. ‘And I’m not inclined to lose it. So let’s forget about that now and you can take us to see the Watch Master.’

‘Lay down—’

‘Yes, yes, so you said. Look.’ I stood up straight and turned to try and catch the moonlight. ‘Prince Jorg. That’s me. Pushed the last Watch Master over the falls. Now take me to Coddin before I lose my famously good temper.’

We reached an understanding and before long I had two of them leading Alain’s horse, and another lighting the way for us with a hooded lantern.

They took us to an encampment a couple of miles further on, fifty men huddled in a hollow just below the saddle of a hill. Brot Hill, according to the leader of the band taking us in. Nice to know somebody had a clue.

The watch brought us in with whistled signals to the guards. The camp lay dark, which was sensible enough given they weren’t ten miles from The Haunt.

We stumbled in amongst sleeping watchmen, tripping over the guys of various tents set up for command.

‘Let’s have some light!’ I made enough noise to wake the sleepers. A prince deserves a little fanfare even if he has to make it himself. ‘Light! Renar doesn’t even know you’ve crossed the borders yet, he’s holding a tourney in the shadow of his walls for Jesu’s sake!’

‘See to it.’ I recognized the voice.

‘Coddin! You came!’

Lanterns began to be lit. Fireflies waking in the night.

‘Your father insisted on it, Prince Jorg.’ The Watch Master ducked out of his tent, his face without humour. ‘I’m to bring your head back, but not the rest of you.’

‘I volunteer to do the cutting!’ Rike stepped into the lantern glow, bigger than remembered, as always.

Men stepped aside, and Gorgoth came out of the gloom, huger than Rike, his rib-bones reaching from his chest like a clawed hand. ‘Dark Prince, a reckoning is due.’

‘My head?’ I put a hand to my throat. ‘I think I’ll keep it.’ I turned to see Fat Burlow arrive, a loaf in each hand.

‘I believe my days of pleasing King Olidan are over,’ I said. ‘In fact I’m even tired of waiting for him to die. The next victory I take will be for me. The next treasure I seize will stay in these hands, and the hands of those that serve me.’

Gorgoth looked on, impassive, little Gog watching from his shadow. Elban and Liar elbowed their way through the growing ring of watchmen.

‘And what treasure would that be, Jorth?’ Elban asked.

‘You’ll see it when the sun rises, old man,’ I said. ‘I’m taking the Renar Highlands.’

‘I say we take him in.’ Rike loomed behind me. ‘There’ll be a price on his head. A princely price!’ He laughed at his own joke, coughing on that fishbone again, the old ‘hur! hur! hur!’

‘Funny you should mention Price, Brother.’ I kept my back to him. ‘I was reminiscing with Makin down at the Three Frogs just the other day.’

That stopped his laughing.

‘I won’t lie to you, it’s not going to be easy.’ I turned nice and slow to address the whole circle of faces. ‘I’m going to take the county from Renar, and make it my kingdom. The men that help make that happen will be knights of my table.’

I found Coddin in the crowd. He’d brought the brothers to me on the strength of my message, but how much further he’d follow me was another matter: he was a hard man to predict.

‘What say you, Watch Master? Will the Forest Watch follow their prince once more? Will you draw blood in the name of vengeance? Will you seek an accounting for my royal mother? For my brother who would have sat upon the throne of Ancrath had I fallen?’

The only motion in the man lay in the flicker of lamplight along the line of his cheekbone. After too long a wait, he spoke. ‘I saw Gelleth. I saw the Castle Red, and a sun brought to the mountains to burn the rock itself. Mighty works.’

Around the circle men nodded, feet stamped approval. Coddin held up a hand.

‘But the mark of a king is to be seen in those closest to him. A king needs be a prophet in his homeland,’ he said.

I didn’t like where we were going.

‘The watch will serve if these … road-brothers stay true, once you have told them of their task,’ he said, eyes on me all the while, steady and calm.

I made another half circle, until Rike filled my vision, my eyes level with his chest. He smelled foul.

‘Christ Jesu, Rike, you stink like a dung heap that’s gone bad.’

‘Wh—’ He furrowed his brow and jabbed a blunt finger toward Coddin. ‘He said you had to win the brothers to the cause. And that’s me that is! The brothers do what I say now.’ He grinned at that, showing the gaps where I’d knocked out teeth under Mount Honas.

‘I said I wouldn’t lie to you.’ I spread my hands. ‘I’m done with lying. You men are my brothers. What I would ask of you would leave most in the grave.’ I pursed my lips as if considering. ‘No, I won’t ask it.’

Rike’s frown deepened. ‘What won’t you ask, you little weasel?’

I touched two fingers to my chest. ‘My own father stabbed me, Little Rikey. Here. A thing like that will reach any man.

‘You take the brothers to the road. Break a few heads, empty a few barrels, and may whatever angel is set to watch over vagabonds fill your hands with silver.’

‘You want us to go?’ He spoke the words slowly.

‘I’d make for the Horse Coast,’ I said. ‘It’s that way.’ I pointed.

‘And what’ll you be doing?’ Rike asked.

‘I’ll go with Watch Master Coddin here. Perhaps I can make peace with my father.’

‘My arse you will!’ Rike hit Burlow in the arm, no malice in it, just an over-boiling of his natural violence. ‘You’ve got it all planned out, you little bastard. Always playing the odds, always with the aces hidden away. We’ll be slogging through dust and mud to the Horse Coast, and you’ll be lording it here with a gold cup in your hand and silk to wipe your shit. I’m staying right where I can see you, until I get what’s mine.’

‘I’m telling you as a brother, you big ugly sack of dung, leave now while you’ve a chance,’ I said.

‘Stuff it.’ Rike allowed himself a triumphant grin.

I gave up on him.

‘Coddin’s men can’t get near that tourney. Men such as us though, we drift into every muster, we lurk at the edges of any place where there’s blood and coin and woman-flesh. The brothers could slip into tourney crowds unseen.

‘When I make my move I need you to hold until the watch can reach us. I need you to hold The Haunt’s gates. For minutes only, but make no mistake, they’ll be the reddest minutes you’ve seen.’

‘We’ll hold,’ Rike said.

‘We will hold.’ Makin raised his flail.

‘We’ll hold!’ Elban, Burlow, Liar, Row, Red Kent, and the dozen brothers left to me.

I faced Coddin once again.

‘I guess they’ll hold,’ I said.

46

‘Sir Alain, heir to the Kennick baronetcy.’

And there I was, riding onto the tourney field to take my place, accompanied by a scatter of half-hearted applause.

‘Sir Arkle, third son of Lord Merk.’ The announcer’s voice rang out again.

Sir Arkle followed me onto the field, a horseman’s mace in hand. Most of the entrants for the Grand Mêlée had can-openers of one sort or another. The axe, the mace, the flail, tools to open armour, or to break the bones closeted within. When you fight a man in full plate, it’s normally a matter of bludgeoning him to a point at which he’s so crippled you can deliver the coup de grâce with a knife slipped between gorget and breastplate, or through an eye-slot.

I had my sword. Well, I had Alain’s. If he had a weapon more suited to the Mêlée, then it left with his guards when they rode off.

‘Sir James of Hay.’

A big man in battered plate, heavy axe at the ready, an armour-piercing spike on the reverse.

‘William of Brond.’ Tall, a crimson boar on his shield, spiked flail.

They kept coming. A baker’s dozen. At last we were all arrayed upon the field. A lucky thirteen. Knights of many realms, caparisoned for war. Silent save for the gentle nicker of horses.

At the far end of the field, in the shadow of the castle walls, five tiers of seating, and in the centre, a high-backed chair draped in the purple of empire. Count Renar rose to his feet. Beside him on the common bench, Corion, an unremarkable figure that drew on the eye as the lodestone pulls iron.

At two hundred paces I could see nothing of Renar’s face save the glint of eyes beneath a gold circlet and a dark fall of hair.

‘Fight!’ Renar lifted his arm, and let it drop.

A knight spurred his horse toward mine. I’d not taken his name to heart. I only listened to the introductions after mine.

All around us men fell to battling. I saw William of Brond take a man from the saddle with a swing of his flail.

My attacker had a flanged mace, clutched tight, the steel of his gauntlet polished to dazzling silver. He shouted a war-cry as he came at me, trailing the mace for an overhead swing.

I stood in my stirrups and leaned toward him, arm fully extended. Alain’s sword found its way through the perforated grille of the knight’s helm.

‘Yield?’

He wouldn’t say, so I let him slip from his horse.

Another knight came my way, sidestepping his horse skilfully away from Sir William’s frenzy. He wasn’t even looking at me.

Around the back of the breastplate there’s a gap just below the kidneys. A decent suit of plate will have chainmail to cover whatever vitals are exposed between breastplate and saddle. And his did. But Builder-steel with a little muscle behind it will cut through chain. The man fell with a vague expression of surprise, and left me facing William.

‘Alain!’ He sounded as if all his Christmases had come at once.

‘I know, I hate him too.’ I flipped my visor.

The thing about flails is you’ve got to keep them moving. An important point that Sir William forgot when he found himself staring into an unfamiliar face. I took the opportunity to urge Alain’s horse forward, and to its credit the beast was fast enough to let me put four foot of razor-edged sword past Sir William’s guard.

It’s not the done thing to set to bloody slaughter at tourney. There’s rarely a Grand Mêlée in which somebody doesn’t die, but it’s normally a day later under the knives of the chirurgeons. The foe is generally unhorsed, or stunned in the saddle. A few fractures and a lot of bruising are the normal consolation prizes distributed among the entrants who don’t win. When a knight gets too thirsty for blood, he often finds himself meeting his opponent’s friends and family in unpleasant circumstances shortly after.

I of course had a rather different view of things. The fewer armed men left able-bodied after the tourney, the better. Besides, a broadsword isn’t the weapon to batter out submissions. It’s for killing, pure and simple.

Sir Arkle charged me, galloping nearly the full length of the field, a felled knight in his wake. As he closed the gap, he set to swinging his mace in a tight pattern just out of kilter with his horse’s gait. It looked worryingly well-practised.

If the sight of a heavy warhorse thundering toward you doesn’t make at least part of you want to up and run, then you’re a corpse. There’s no stopping a thing like that. A thousand pounds of muscle and bone, sweating and panting as it hurtles your way.

I rolled out of the saddle as Sir Arkle arrived. I didn’t just duck. He was ready for that. I fell. And yes it hurt. But not so much that it stopped me sticking old Alain’s sword into that blur of thrashing legs as Arkle hurtled past.

That’s another thing that isn’t done in tourney. You go for the man, not the horse. A trained warhorse is frighteningly expensive, and be assured that when you break one, the owner is going to come after you for the price of a replacement.

I levered myself up, cursing, splattered with horse blood.

Sir Arkle lay under his steed, deathly quiet and still, in contrast to the horse’s screaming and thrashing.

A lot of animals will suffer horrific injury in silence, but when they decide to complain, there’s no holds barred. If you’ve heard the screams of rabbits as they’re put to the knife you’ll know what racket even such small creatures can make. It took two swings to fully silence Arkle’s horse. Another two for good measure to take its head off.

By the time I’d finished, I’d become the archetypal Red Knight, my armour bright with arterial blood. I had the stink of battle in my nose now, blood and shit, the taste of it on my lips, salt with sweat.

There weren’t many of us left standing in the tourney ring. Sir James stood amid a scatter of fallen knights at the far end, battling a man in fire-bronzed armour. Closer to hand an unhorsed knight with a war-hammer had just laid out his opponent. And that was it.

The hammer-man limped toward me, the iron plates around his knee buckled and grating.

‘Yield.’ I didn’t move. Didn’t so much as raise my sword.

A moment of silence. Nothing but the distant clash of weapons as Sir James of Hay put down his man. Nothing but the faint pitter-pat of blood dripping from my platemail.

Hammer-man let his hammer fall. ‘You’re not Alain Kennick.’ He turned and limped toward the white tent where the healers waited.

Half of me wanted the fight. More than half of me wondered if a hammer between the eyes wasn’t a whole lot more appetizing than meeting with Corion again. It seemed impossible that he didn’t already know I was here, that those empty eyes hadn’t seen through Alain’s armour at the first moment. I glanced toward the stands, closer now. He watched me, they all did, but this was the man who’d given me the power to fell Brother Price, the man who whispered from the hook-briar, who poisoned my every move, pulling the strings toward hidden ends. Had he drawn me here, to this moment, tugging on his puppet lines?

Sir James of Hay put an end to my speculation. He dismounted, presumably having noted my lack of respect for horseflesh, and advanced with purpose in his stride. The sunlight coaxed few glimmers from the scarred plates of his armour. His heavy axe had done good work today. I saw blood on the armour spike.

‘You’re a scary one,’ I said.

He came on, stepping around Arkle’s horse.

‘Not a talker?’ I asked.

‘Yield, boy,’ he said. ‘One chance.’

‘I’m not sure we even have choices, James, let alone chances. You should read—’

He charged, dragging that axe of his through the air in a blur. I managed a block, but my sword flew free, leaving my right hand numb to the wrist. He reverse-swung, his strength tremendous, and nearly took my head. I swayed aside, clear by half an inch, and staggered back.

Sir James readied himself. I knew then how the cow feels before the slaughterman. I may have been guilty of fine words about fear and the edges of knives, but empty-handed before a competent butcher like Sir James I found a sudden and healthy terror. I didn’t want it all to end here, broken apart before a cheering crowd, cut down before strangers who didn’t even know my name.

‘Wait!’

But of course he didn’t. He came on apace, swinging for me. If I hadn’t tripped as I backed, I’d have been cut in two, or as near as makes no difference. The fall left me flat on my back with the air knocked out and Sir James carried two strides past me by his momentum. My right hand, grasping for purchase, found the haft of the discarded war-hammer. The old luck hadn’t deserted me.

I swung and made contact with the back of Sir James’ knee. It made a satisfying crunch, and he went down, discovering his voice on the way. Unfortunately the brute hadn’t the grace to know he was supposed to be beaten. He twisted onto his good knee and raised his axe over my head. I could see it black against the blue sky. At least the sun was out. A blank visor hid his face, but I could hear the rattle of his breath behind it, see the flecks of foam around the perforations.

‘Time to die.’

He was right. There’s not much to be done with a war-hammer at close quarters. Especially when you’re spread-eagled on your back.

ChooOm!

Sir James’ head jerked from my field of view leaving nothing but blue heaven.

‘Gods but you’ve got to love that crossbow!’ I said.

I sat up. Sir James lay beside me, a neat hole punched through his faceplate, and blood pooling behind his head.

I couldn’t see who had taken the shot. Probably Makin, having regained the Nuban’s crossbow from one of the brothers. He must have loosed his bolt from the commons where the rabble stands. Renar would have men stationed where anyone might get a clear shot at the royal seating area, but targeting the combatants on the field was a far easier proposition.

I recovered my sword before the crowd really took in what had happened. A scuffle of some kind had broken out in the commons, a large figure in the midst of it all. Rike breaking heads perhaps.

I scooped up Sir James’s axe and caught Alain’s horse again. Once in the saddle I took axe and sword in hand. Townsfolk began to stream onto the field with some kind of riot in mind. It wasn’t entirely clear where their anger lay, but I felt sure a whole lot of it rested on Sir Alain of Kennick.

A line of men-at-arms had positioned themselves in front of the royal stand. A squad of six soldiers in castle livery were angling toward me from their station by the casualty tent.

I lifted axe and sword out to shoulder height. The axe weighed like an anvil; it’d take a man like Rike to wield it as lightly as Sir James had.

From the corner of my eye I could see guards leaving their posts at the castle gates to help calm the disturbance and come to their lord’s aid.

Corion found his feet, oddly reminiscent of a scarecrow, standing just below Count Renar’s seat. The Count himself remained in his chair, motionless, hands in his lap, fingers steepled.

Did Corion know it was me? He had to, surely? When I’d broken his spell, when I’d woken from dark dreams after Father’s tender stab, and finally remembered how he’d turned me from my vengeance, how he’d made me his pawn in the hidden game of empire, hadn’t he known?

Time to find out.

I urged Alain’s horse into a canter and aimed him straight at Renar, axe and sword in outstretched hands. I hoped I looked like Hell risen, like Death riding for the Count. I could taste blood, and I wanted more.

There really is something about a heavy warhorse coming your way. The stand began to empty at speed, the gentry climbing over each other to get clear. A space opened up around Renar’s high-backed chair, just him, Corion, and the two chosen men flanking. A ripple even ran through the line of soldiers before the seating, but they held their ground. At least until I really picked up speed.

47

Alain’s horse carried me through the soldiers, up the stands, like climbing a giant staircase, right to Count Renar’s chair, and through it.

Had the Count not been hauled from his seat moments before, it could have all ended there.

‘Get him away!’ Corion said to the quick-handed body-guard.

The other chosen man came straight for me as the horse beneath me panicked at the strange footing. I couldn’t control the beast, and I didn’t want it to land on me when it fell, so I leapt from the saddle. Or got as close to a leap as a man in full plate can, which is to say that I chose where I fell. I trusted to my armour and dropped onto Renar’s bodyguard.

The man cushioned my fall, and in exchange got most of his ribs broken. I heard them crack like sappy branches. I clambered up, with the horse whinnying behind me, hooves flying in all directions as it turned and bucked, threatening to fall at every moment.

I threw Sir James’ axe at Renar’s back, but the thing proved too heavy and ill-weighted for a clean throw. It hit his second bodyguard between the shoulderblades and felled him. Renar himself managed to reach the soldiers I’d scattered in my charge, and they circled around to escort him toward the castle.

I took my sword in two hands and made to follow.

‘No.’

Corion stepped into my path, one hand raised, a single finger lifted.