Полная версия

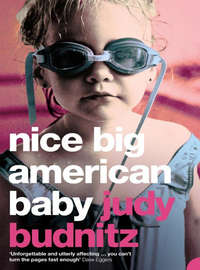

Nice Big American Baby

She looks for the Hopper man. She assumes he would have disappeared by now, but no, there he is. “Don’t be mad, little mama,” he says. “I told you there were no guarantees.”

She stamps her foot. The pressure inside her is unbelievable. But she wills her body to hold itself together.

“Tell you what,” he says. “How about I set up another trip for you? Free of charge? Because I’m such a nice guy?”

“Not the truck. The driver was bad. I think he told the border police where to find us.”

“That’s terrible,” the man says. “You just can’t trust anyone, can you? I won’t use him again.”

The second time is on a boat, a huge boat, a cargo ship. She doesn’t know what it’s carrying; the cargo could be anything; it’s packed into truck-sized metal rectangles, stacked up in anonymous piles.

She and twelve others hide in the hold. It’s dank, dark, cramped, but the gentle motion of the boat soothes her; this is what it must feel like for her son, she thinks.

Her son is very still. She worries that he is dead, but she tells herself that it’s only because he’s grown too big, has no room to move. Just a little longer, she thinks, and then you can come out and begin your new life. Some people told her America’s territory extends from its coastline, fifty miles into the ocean. Others have said five miles. She wants to wait for solid land to be absolutely sure.

But they’re stopped almost immediately. She and the others are sought out with flashlights, led up to the deck, and lowered into a smaller boat that speeds them back to the harbor. She would have tried to run, to hide, if not for her son. Any violent motion, she fears, will bring him tumbling out. If she jumped in the water, he might swim right out of her to play in the familiar element.

“My goodness,” the Hopper man says when he sees her. “Are you having twins?”

“Your boat people are bad,” she says furiously. “They told the border people we were there.”

“You don’t say! I certainly won’t be using their services anymore.”

“I think the border people pay them money to turn us in. A price for each person.”

“What makes you think that?”

She has heard people arguing, pointing at her and arguing over whether she should bring the price of one or two.

“We’ll get you over there,” the man says. “I give you my promise. Three’s the charm.”

The next time, she rides in a hiding place built between the backseat and trunk of a small car. They have trouble shutting her in; her belly gets in the way. It seems luxurious, after the first two trips. She has the space to herself. A man and woman sit in the front. On the backseat, inches from her, a baby coos in a car seat. She doesn’t know if it’s their baby or someone else’s, a borrowed prop. Her son shifts irritably, probably sensing the other baby, probably thinking, Now that’s the way to travel.

At the border they’re stopped, the trunk is opened. The panel is ripped away, and for the third time she’s blinking in bright light. She imagines her son beating his fists against the sides of her womb.

Not yet, she thinks, not yet, my son. Just a little longer.

She’s now nearing the end of her tenth month. Her belly is strained to the breaking point, her back aches, her knees buckle. But she’s more determined than ever. And her son seems to be as stubborn as she is.

“Now it looks like quadruplets,” Hopper says.

“He’s going to be an American baby,” she says, through gritted teeth. “Babies are bigger there. A nice big healthy American baby.”

“Is that what he told you?”

“He’s not going to come out until we get there,” she says.

“I’ll do what I can,” he says. “No guarantees.”

She’s been told there are places where you can climb over the fence. There are places where there is no fence, only guards in towers who sometimes look the other way. She’s going to take her chances on her own. Enough of his gambles.

“I wish you the best,” he says, tipping his fishing hat.

She can barely walk; she stumbles, lurching and weaving. Other people look at her and say, “There’s no way. It’s impossible.” She ignores them.

She walks, through scrub brush and rocks and burning sand and stagnant, stinking water. She walks and walks, thinking: American baby. Nice big American baby.

She hears a sound echoing from far away: dogs yelping, frenzied. She can almost hear them calling to one another: There she is, there she is, get her.

They burst over a rise and she can see them, a mob of dark insects growing rapidly bigger, a man with a gun trailing far behind. Has she crossed the border already? It’s impossible to tell.

The first dog runs straight at her. She stands still and waits. It seems nearly as big as she is, a small horse. At the last minute it veers away and circles. All the dogs swarm around her. But they do not touch her. They keep their heads lowered abjectly to the ground. They seem in awe of her big belly.

The fat sweating guard who comes puffing up behind them is not impressed. Soon she’s sitting in a familiar van, heading back.

She’s been carrying her son for over a year now, with no intention of letting him go.

“Now, that can’t possibly be good for him, little mama,” Hopper says. “You should let the little feller out.”

“He’s going to be an American baby,” she says, slowly, as if talking to a child.

“Let me help you,” he says. “I know a man—”

“No,” she says.

“We’ll try another way. I can get you a fake passport.”

“No,” she says. She hobbles back to the border, is stopped by a fence, and begins tunneling under it, clawing the dirt with her fingernails. She’s crawling through, nearly breaking the surface on the other side, when her son shifts, or perhaps instantaneously grows a fraction of an inch, and suddenly she’s stuck. Border guards come and drag her out by her heels. They don’t seem surprised, they seem as if they’ve been expecting her. They look bored, almost disappointed, as if they’d expected her to have a little more originality.

“Why won’t you let me help you?” Hopper says.

She doesn’t answer.

“Free of charge.”

“Why are you being so generous?”

“I don’t know. Out of the goodness of my heart?”

Today he’s wearing a bolo tie, a snakeskin vest. He is wearing rings on every finger, like a king, like a pirate. Like a pirate king.

“Please,” he says. “I want to. I insist.”

She realizes something she should have seen months ago. He’s been tipping off the border guards. He takes money from people for helping them cross; then he takes money from the guards for telling them when and where to expect visitors. She’s been making money for him with each of her trips.

“You are a bad man,” she says.

“Oh, come now,” he says. “You can’t blame me. It’s a game of chance.”

“An evil man. When my son gets big he’ll come back and kill you.”

“Your son’s already big,” he says. “And I don’t see him doing anything.”

She is determined. She flings herself at the border again and again. She travels in cars, trucks, buses. She walks on blistered feet. She travels in a fishing boat, an inflatable raft. She wears disguises, buys false papers. Each time the border repulses her, spits her back.

Big American baby, she tells herself. She sees his size as proof of his American-ness. Only American babies could be so big, so healthy. She has convinced herself that he has always been American, that she is merely a vehicle, a shell, a seed casing meant to protect him until he can be planted in his rightful home.

She carries him for two years. She constructs a sort of sling for herself, with shoulder straps and a strip of webbing, to balance the weight. She uses a cane. She looks like a spider, round fat body, limbs like sticks.

Her son is alive; she can feel the pulse of his heartbeat, feel the pressure as he strains to stretch a finger, an eyelid.

She thinks she can see a dark shadow through the taut translucent skin of her belly. She can see his hair growing long and black.

Her body is adaptable. Her skin stretches, her bones shift, her blood feeds him. When people see her they are amazed, but she is not; she has seen it before, the lengths the body will go to to preserve itself, to cling to life.

Big American baby, she thinks. Nice big American baby. It is her mantra.

She carries him for three years. Three and a half. She becomes a legend, then a joke, with the border guards. They wave to her as she creeps past, cheer her on, drag her back at the last minute.

Don’t you think he wants to come out by now? people at home say to her.

He’s safer living in my belly than in this wretched country, she says, though she has been so single-mindedly set on her mission that she has taken no notice of external events. War, famine, peace, prosperity: it is all the same to her. America is the only option, the only ray of hope.

She carries him for four years.

Big American baby. Nice big American baby.

She has in her mind pictures of hot-air balloons attached to bicycles, fanciful flying machines. Some days she imagines she will simply lift off the ground and float over, suspended by the power of her will alone. Hers and her son’s. Or she imagines that she is invisible, intangible; she breezes across the border. The air, it seems, is the only thing that crosses freely.

Her son is so big, she imagines he fills her completely, his arms fill her arms, his legs fill her legs. She is a mere skin covering him, like an insect’s carapace, soon to be flaked off and shucked away.

She’s too tired to speak now, just pants and whistles through her teeth. The words rattle in her head.

Nice big American baby, someone chants. Not her. Him. The voice of her son gurgling up from her belly. Muffled and airless but undeniable.

My son’s first words, she thinks, smiling proudly at a shriveled bush. You hear that? No baby-talk preliminaries, no babbling or lisping. My son: so precocious, so American.

One day, as she is panting out her mantra and picking her way across the sand, a border guard appears: suddenly, as if he sprang up out of the ground. He carries the usual gun, wears the usual impenetrable sunglasses, has the regulation sweat stains blooming from his armpits. He takes her arm. She obediently turns around and begins walking back. She does not want him to start pushing her, getting rough; the baby might come out.

But to her surprise she finds him pulling her forward, forward across the magic invisible line. Forward, toward the magnificent city that hovers like a mirage in the distance.

“Come on, little mama,” he says. “You’ve had enough.”

When she closes her eyes she sees the hospital of her dreams, a white sparkling grand hotel. When she opens them she sees speckled ceiling tiles, masked alien faces. She can’t feel a thing; she’s a floating head. It’s finally happened, then: her stubborn impatient head has taken off and left the slow body behind somewhere to gestate, egg and nest all in one.

“My son,” she says.

“He’s coming,” they tell her. They have to operate. “There’s no way he’s fitting through the usual door,” they tell her.

She sees a foot kicking. It’s as long as her hand. She hears a stupendous, deafening roar. The foot catches one of the masked doctors on the chin and sends him flying backward into the spattered arms of another masked figure.

Her balloon head is bobbing near the ceiling now, borne on the baby’s howls, but she’d swear she can hear, interspersed with the empty cries, bellowed words. I want, the baby demands. Give me, I want, I need, I deserve, I have earned.…

She sees rising up out of her tired body a sodden mop of long black hair. She sees grasping fists.

She hears—and surely she must be dreaming now—she hears the scrape of a rubber-gloved hand rubbing a sore chin and a doctor’s voice saying, “Now that’s what I call a nice big American baby.”

Empty, deflated, she sits alone in the back of the van. She hears weeping somewhere, mingled with the sounds of tires on asphalt. It must be the driver. It can’t be her. Can it? Impossible. There’s nothing inside her to come out, not a drop. She’s hollow, she’s still floating, they forgot to reattach her head to those rags and remnants that were her body.

“But it’s what you wanted, isn’t it? Wasn’t that the whole plan, give birth and leave him here with a new set of folks?”

“I never even got a chance to hold him.”

“He’s too big for holding already. He could hold you.”

“I had things to say. Stories to tell him.”

“He heard them. He was listening, all those years when you talked to him. He’ll remember.”

It’s the voice of the Hopper man; she’s not sure if he’s the man driving the van or if the voice is inside her head. It doesn’t matter.

“I want to stay,” she whispers. “He’s mine.”

“You can always have another.”

3. after

The prospective parents had applied for a newborn baby, so they did not know what to make of the walking, talking child they visited at the temporary foster home. The adoption agent assured them he had been born only a few days earlier. “I have his birth certificate right here,” she said.

Maybe children these days grow up faster than they used to, the hopeful parents told themselves. We should have studied the child development book more carefully, they thought.

They did not voice their doubts, fearing they’d reveal their inexperience, their ignorance. One slip of the tongue and their application would be rejected.

They felt intimidated by the adoption agent, who handled babies as carelessly as basketballs, and also by the foster mother, who had eight children in her charge.

The prospective mother had been looking forward to the cuddling, burping, nurturing years; she’d been gearing herself up for sleepless nights of colic and lullabies and martyrdom. The child before them, calmly regarding them with large brown eyes, was already far beyond that stage. Yet there was something so appealing, so desirable, so eminently wantable about him that both prospective parents found themselves smitten. They had to have him. He sat on the carpet knocking one block against another, seemingly bored, covertly watchful. They both felt a quickening in their hearts: the anxiety of bargain hunting—the sensation that if they did not get him immediately, someone else would come along, perceive his value, and snatch him up.

When they brought him home he ran through the house pointing at things, wanting to learn their names. “Microwave,” they said. “Piano.” “Baby monitor.” “Treadmill.” “Shoe tree.” “Television.”

They were charmed by his curiosity. Privately they fretted over the way he stiffened whenever they touched him. He was remote, as patiently tolerant as a teenager suffering the whims of unhip parents.

He just needs time, they thought, to get used to us.

What does bonding mean, exactly the new mother wondered. She thought of the unknown woman, the biological mother who’d carried the boy inside her body for nine whole months, and realized she was jealous.

The boy was too well-behaved, too precocious, too perfect. It made them nervous. His perfection made him seem vulnerable, ripe for spoiling. Doesn’t it seem like the perfect, angelic little boys are always the ones to get cancer, get hit by cars? the mother thought.

He never made any mistakes. If there were mistakes to be made, they’d be made by the parents. So they washed everything twice, planned educational vacations. The pressure was excruciating.

He’d been their son for over a year when he told them about the face.

He appeared at their bedside in the middle of the night, white and glowing in his astronaut pajamas. “Can I come in?” he said.

They relished the moment, kissing him, tickling him, tucking him in between them.

“Did you have a bad dream?” the mother said.

“There was a face in the window,” the boy said, and described glittering eyes and shining teeth and a wiry net of hair, long fingers scrabbling at the sill and warm breath that seeped into the room. A sad face. It watched him for a long time, he said, not moving.

“It isn’t real,” the father said. “It’s only a dream.”

The mother thought of goblins, gypsies, pirates, a hundred fairy tales of stolen children. She tightened her grip. “We’ll protect you,” she whispered fervently. “We’ll never let anyone take you away.”

“Take me away?” the boy said. The father groaned softly.

She realized she’d made a blunder, planting a new fear in his head that had not been there before.

The next day the father made a great show of testing the locks on the boy’s bedroom window. He pointed out the tree branches that moved in the wind like hair. He talked about the damp smells rising up from the basement, the stink and scrabbling of skunks digging through the garbage cans. The boy listened impassively.

For the next few nights the boy slept peacefully. The parents did not.

And then he was back, glowing in the dark, his feet padding across the floor. “It’s back,” he said calmly. They lifted their covers for him, pleased that he was finally having the normal problems of a normal child.

The face came back periodically. Not often, but every few weeks. The parents tried to dispel the son’s fears, but with less and less enthusiasm as time went on. They worried that if the nightmares stopped, the tenuous intimacy with their son would be gone forever. The mother, in her heart of hearts, secretly made contingency plans—if his nightmares stopped, she’d simulate them (a Halloween mask dangled from the roof, say).

If she left the imprint of a finger in his sandwich, her son would eat around it and leave the little island on his plate. He continued to flinch at the touch of her hand. Still, she sometimes wondered if he was secretly starved for affection, if he’d fabricated the face story as an excuse.

Or maybe, she thought, he’d invented the face as a way of comforting them. She wouldn’t put it past him, her wise little son.

In the night she stroked her son’s shoulders and kissed the top of his head. She wrapped her arms around him and pretended he was inside her.

The next morning she went into his room to make the bed and found the window open and the curtains frothing in the wind. She felt a momentary panic—danger! falling baby!—but the window guard was still in place. She closed the window and locked it. As she was turning away she noticed fingerprints spotting the glass. She must have done that herself, just now. How careless. I’ll clean it later, she thought, and bent to the bed, brushing away a few of her son’s long black hairs.

To her surprise, she found the bottom sheet damp. Never before had her son wet the bed. She dipped her fingers in the wet spot, feeling fascinated, amazed, intensely maternal. My son, she thought proudly, wets the bed. She imagined telling a friend about it. Oh, yes, like any normal child, he wets the bed occasionally. When he has a nightmare. What can you do? No, of course we’re not worried about it. He’ll outgrow it eventually.

But still there was something strange about it.… The stain was perfectly clear; it looked like water. And rather than one spot it was composed of many, a string of drops.

She glanced around furtively to make sure she was alone, then raised her wet fingers to her nose. She smelled nothing. She put her fingers to her tongue. The wetness tasted like tears.

flush

I called my sister and said, What does a miscarriage look like?

What? she said. Oh. It looks like when you’re having your period, I guess. You have cramps, and then there’s blood.

What do people do with it? I asked.

With what?

The blood and stuff.

I don’t know, she said impatiently. I don’t know these things, I’m not a doctor. All I can tell you about anything is who you should sue.

Sorry, I said.

Why are you asking me this? she said.

I’m just having an argument with someone, that’s all. Just thought you could help settle it.

Well, I hope you win, she said.

I went home because my sister told me to.

She called me and said, It’s your turn.

No, it can’t be, I feel like I was just there, I said.

No, I went the last time. I’ve been keeping track, I have incontestable proof, she said. She was in law school.

But Mitch, I said. Her name was Michelle but everyone called her Mitch except our mother, who thought it sounded obscene.

Lisa, said Mitch, don’t whine.

I could hear her chewing on something, a ballpoint pen, probably. I pictured her with blue marks on her lips, another pen stuck in her hair.

It’s close to Thanksgiving, I said. Why don’t we wait and both go home then?

You forget—they’re going down to Florida to be with Nana.

I don’t have time to go right now. I have a job, you know. I do have a life.

I don’t have time to argue about it, I’m studying, Mitch said. I knew she was sitting on the floor with her papers scattered around her, the stacks of casebooks sprouting yellow Post-its from all sides, like lichen, Mitch in the middle with her legs spread, doing ballet stretches.

I heard a background cough.

You’re not studying, I said. Neil’s there.

Neil isn’t doing anything, she said. He’s sitting quietly in the corner waiting for me to finish. Aren’t you, sweetheart?

Meek noises from Neil.

You call him sweetheart? I said.

Are you going home or not?

Do I have to?

I can’t come over there and make you go, Mitch said.

The thing was, we had both decided, some time ago, to take turns going home every now and then to check up on them. Our parents did not need checking up, but Mitch thought we should get in the habit of doing it anyway. To get in practice for the future.

After a minute Mitch said, They’ll think we don’t care.

Sometimes I think they’d rather we left them alone.

Fine. Fine. Do what you want.

Oh, all right. I’ll go.

I flew home on a Thursday night, and though I’d told them not to meet me at the airport, there they were, both of them, when I stepped off the ramp. They were the only still figures in the terminal; around them people dashed with garment bags, stewardesses hustled in pairs wheeling tiny suitcases.

My mother wore a brown coat the color of her hair. She looked anxious. My father stood tall, swaying slightly. The lights bounced off the lenses of his glasses; he wore jeans that were probably twenty years old. I would have liked to be the one to see them first, to compose my face and walk up to them unsuspected, like a stranger. But that never happened. They always spotted me before I saw them and had their faces ready and their hands out.

Is that all you brought? Just the one bag?

Here, I’ll take it.

Lisa, honey, you don’t look so good. How are you?

Yes, how are you? You look terrible.

Thanks, Dad.

How are you? they said, over and over, as they wrestled the suitcase from my hand.

Back at the house, my mother stirred something on the stove and my father leaned in the doorway to the dining room and looked out the window at the backyard. He’s always leaned in that doorway to talk to my mother.

I made that soup for you, my mother said. The one where I have to peel the tomatoes and pick all the seeds out by hand.

Mother. I wish you wouldn’t do that.

You mean you don’t like it? I thought you liked it.