Полная версия

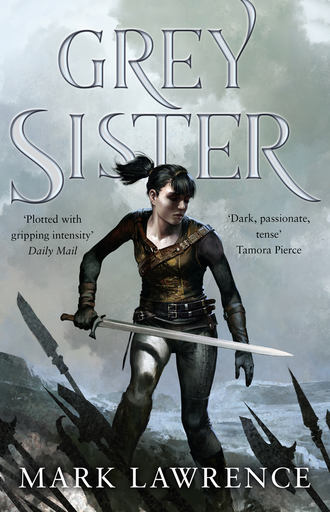

Grey Sister

After the rising turns came a scramble up a rock fall, with the cavern roof slanting just three feet above. Finally a cliff some twenty yards high, perhaps once a waterfall, the wet stone offering few handholds. Fortunately the old watercourse had allowed room to swing and throw a grapple. The locating and pilfering of both rope and hook had taken a week but the hours spent trying to catch some edge far above them had seemed much longer. On perhaps the seventieth throw Darla had snagged the hook and Ruli, the lightest of them, had scrambled up. The rope was now secure and knotted at intervals. Climbing it brought them to the limits of their exploration, a roundish chamber, mud-floored, from which three new passages led.

Nona stood with Ara, Jula, and Ruli, catching their breath, staring at the exits, Ketti and Darla still climbing behind them.

‘I want to get under the convent,’ Nona said. She blinked. She hadn’t been intending to speak, but now the words had left her mouth she realized it was better that the truth was out. For three years she had seen the only route to revenge on Yisht to be training. To make herself into a weapon suited to the task of finding then destroying the woman. Neither would be easy. The empire was large, and Yisht expert at hiding, deadly when found. Nona had been very lucky in their first encounter and had still only just survived. But Joeli’s taunting had put into Nona’s mind the idea that there might be some clue at the spot where Hessa died. Something the nuns overlooked. Something her friend left for her alone. It was a very faint hope. Too faint perhaps to justify exposing her companions to such dangers … but Joeli’s words were an itch that refused to be scratched. ‘Hessa’s name is so important to you? And yet you’ve never even visited the spot where she died.’ The accusation repeated in her mind, an echo that grew rather than died away.

‘I need to visit the shipheart vault.’ Nona spoke the words into the silence that had followed her first statement.

‘Because we won’t be in enough trouble just for being in the tunnels,’ Ruli said. ‘We should go where we’re more likely to be caught and will have broken more rules.’

Jula frowned. Despite her cleverness sarcasm always seemed to go over her head. ‘But—’

‘I’m banned from leaving the convent until next seven-day in any case,’ Nona said. ‘So if I’m right under it I’ll be breaking fewer rules.’

‘Go back to the vault?’ Ara asked, raising her lantern to inspect Nona’s face. ‘That’s madness. Abbess Glass will throw us out. You know what she said about the undercaves!’

‘I have to.’ Nona had to see it for herself. She had to set her hands to the spot where Hessa had died. Perhaps some clue remained that would help her find Yisht. ‘I have to. For Hessa. I felt her die. The rocks. Yisht’s knife. I felt all of it. If there’s justice to be had, or revenge, it starts there, where it happened.’

‘I don’t want to go near the convent. The sinkhole’s too close.’ Ketti got to her feet behind them after finishing the climb. ‘There could be tunnel-floods.’ She shuddered.

‘I still say they’ll have the undercaves blocked off.’ Darla followed Ketti into the chamber, brushing grit from her habit.

‘Maybe. But it’s as good a direction to explore as any other,’ Ara said. Nona thanked her silently.

‘I don’t know …’ Darla shook her head. ‘The abbess wasn’t joking when she put the undercaves off-limits. She wrote it in the book and everything …’

‘That was over two years ago.’ Ara came to Nona’s defence. ‘Plus, if they didn’t know Yisht was there for all those weeks and she was going to and fro from her room, they won’t know we’re there if we come from underneath for a quick look. Right, Nona?’

Nona nodded. She owed it to Hessa. She had let years slide by and done nothing to avenge her. Her friend had died and Nona had hidden in the convent, well fed, cared for, whilst Yisht walked the world with Hessa’s blood on her hands. But though the Corridor might be a narrow girdle to the globe it was still too wide for a lone child to find a woman like that who didn’t want to be found. And Yisht was an ice-triber. She might be anywhere in the vastness of the ice. ‘I can’t do this alone.’ The gate to Shade class had a sigil-scribed lock now: the thing would have to be blown off its hinges to gain access without the key. Coming at the Dome of the Ancestor and the shipheart chamber from below was the best option.

‘I’ll help.’ Jula spoke up, her voice thin in the cavern’s void.

Nona offered her a smile. Jula put an arm around her shoulders for the briefest hug.

‘So …’ Nona, even less at ease with physical affection than Jula, waved a hand at the tunnel mouths.

‘That one.’ Jula pointed to the leftmost tunnel, boulder- choked and leading down. She had an instinct for direction below ground that had proved uncanny. ‘Though it doesn’t look very safe.’

Ara led on and they followed, stepping over fallen rock, some of it still jagged. After a hundred yards or so the passage broadened and became a cavern so wide it swallowed their light and gave nothing back. For a moment Ara halted and they all held quiet listening to the silence and to the drip … drip … drip of water that was somehow part of the vastness of the silence. Nona glanced about at the novices around her, all illuminated on one side and dark on the other, and for an instant found herself outside her body, suddenly aware of herself as a tiny mote of life, warmth, and light in the black and endless convolutions of the cave system. Now more than ever she felt the irony that the Rock of Faith, named for the foundations of their religion, lay rotten with voids and secret ways, permeable and ever-changing.

‘We should go across,’ Jula said, her voice small in all that empty space. She didn’t sound as if she wanted to.

Ketti marked the wall with her chalk and drew an arrow on the floor.

‘We should follow the wall. We’re less likely to get lost,’ Darla said.

Ara took them to the left, staying close to the wall. Stalagmites rose in small delicate forests, stalactites descended in curtains where the cave curved down, glistening with an iridescent sheen like the carapace of a beetle.

‘Stop.’ Ruli turned and stared into the darkness beyond the lanterns’ reach. Nona stopped, the others too.

‘What?’ Jula raised her light.

‘Didn’t you hear it?’

‘No.’ Darla loomed beside her, her shadow swinging.

‘Something’s out there, coming for us,’ Ruli said, wide-eyed.

‘There’s nothing living in these caves,’ Darla said. ‘We would have seen bones or dung. What did it sound like?’

‘Dry.’ Ruli shivered.

‘Dry?’

‘I want to go back,’ Ruli said.

Ara advanced a few yards, lantern high. ‘There’s something here.’

Nona crowded forward with the others, leaving Ruli in deepening shadow.

‘What is it?’ Ketti frowned.

To Nona’s eye it seemed that a shadowy forest of misshapen stalagmites covered the cavern floor, some curving over in ways that such growths are not supposed to.

‘Bones.’ Jula saw it first.

From one instant to the next the scene switched from one of confusion to one of horror. Skeletons, calcified like those back in the niche, but more thickly: dozens of them.

‘Some of these have been here for an age.’ Ara pointed to a stony ribcage from which straw-thin stalactites dripped, and to a skull distorted by the weight of stalagmite growing upon it, like a candle from which half the wax had run.

Jula bent over to inspect something by the wall.

‘We really need to go!’ Ruli called at them, not having moved from where she stood. ‘Can’t you feel it?’

‘I don’t …’ But then Nona felt it and held her tongue. Something scraping at the edges of her senses, a dry touch from which her mind recoiled.

Holothour.

What?

Nona felt Keot moving beneath the skin of her back. Normally he was silent in the caves.

You should run.

You always tell me to fight.

Now I’m telling you to run.

‘We should go back. Now!’ Nona turned to follow Ruli who had already started to run back the way they came, into the blind darkness.

‘What’re you scared of?’ Darla called after them. ‘There’s nothing here.’ She laughed. ‘And neither of you have a lantern.’

Nona stopped at the margins of the lighted area, infected by a disembodied fear.

What’s out there, Keot?

Something Missing-bred. Something hungry. Run!

‘We need to go. Trust me.’ Nona’s voice sounded thin in the emptiness of the cavern. Behind her the sounds of Ruli’s stumbling panic.

Ara frowned then followed. ‘I don’t understand you, but I trust you.’ Jula fell in behind her. Darla, with the light now retreating from her, snarled in frustration and hurried after them.

The six novices picked up the pace, shadows swinging all around them. Nona could make out Ruli ahead, feeling her way. With each passing moment it seemed that something gathered itself behind them, as if the space now echoing with their footfalls was drawing in its breath. Nona felt the horror of it crawl along her spine. The darkness held something awful. Something ancient and waiting. The need to be gone made her heart pound and tightened her breathing into gasps.

‘Oh blood!’ Even Darla felt it now, her face white.

Nona knew with cold certainty that beyond the margins of their illumination the calcified bones stretched out yard upon yard, innumerable victims lying in meticulous order. How many centuries had they watched the darkness? And she knew that among them paced a horror. She felt it now, individual, condensing out of the night, taking form. Perhaps it wore a man’s shape. Perhaps even her own. And if it ever raised its face to her she would drown in nightmare.

By the time they reached the chamber where they had chosen between the three unexplored passages all of them were running. Ruli was already on the rope. Jula didn’t wait for her to get off. Ara stood with her back to the cliff, lantern high, staring at the tunnel mouth. Ketti and Darla crouched by the edge urging the others down. It was all Nona could do not to push between them and make her own grab for the rope.

‘Ancestor! Hurry it up!’ The cry broke from her.

Ruli and Jula reached the bottom together and went sprawling in a clatter of loose stones. Ketti began to climb. The darkness in the tunnel seemed to thicken, rejecting the light from Ara’s lantern.

‘It’s coming!’ Darla was sliding over the edge, hands white on the rope, her feet just a yard above Ketti’s head.

‘We can’t stay!’ It was all Nona could do not to scream. Fear filled her, trembling in every limb, fluttering the breath in her lungs. ‘Ara, come on!’

They descended the rope on top of one another, lanterns hooked to belts, burning their palms as they slipped from knot to knot.

A confusion of swinging lanterns, sharp rocks, and snatching shadows followed. Screaming, panting, glimpses of chalk symbols, running, scrambling, and finally a desperate squeeze and they lay in the improbable brightness of day, sprawled on the Seren Way, gasping for breath.

There in the light, with a cold wind blowing and the plains stretching out below them towards the distant smokes of Verity their flight seemed suddenly foolish.

‘I’m never going in there again. Ever.’ Darla rolled over onto her back, her habit torn and smeared with mud.

‘What were we running from?’ Ketti asked.

‘The first time when serenity would have really helped us …’ Ara sat up, shaking her head.

‘And we ran!’ Nona couldn’t believe she hadn’t reached for her serenity. Some novices still took a while to sink into the trance but many could summon the mindset in a few moments. The fear had got into her before she thought to wall it away.

‘Ancestor! Look at us!’ Jula stretched out her habit. Grey underskirt showed through a tear as long as her hand. Nona glanced down at herself. Smears of mud streaked her in horizontal lines where she had collided with walls on the mad dash out.

‘Sister Wheel will kill us!’ Ruli examined herself in horror.

‘Sister Mop you mean,’ Ara said.

‘Both of them will!’ Ketti jumped to her feet. ‘Let’s get back!’

‘You’re worried about Wheel and Mop?’ Nona pointed at the dark slot hidden back along the cliff side. ‘What about that. Just now?’

Jula frowned and brushed a grimy hand back over her hair. ‘I’m not going in there again.’ She looked down at the rip. ‘Oh, we’re in so much trouble.’

Darla followed Ketti, muttering to herself. Jula and Ruli set off up the track behind them. ‘Ara?’ Nona stood amazed. ‘What happened in there? Why are they just leaving?’

Ara looked puzzled. The smudge of dirt below her right cheekbone just seemed to make her more beautiful. She narrowed her eyes as if trying to capture some memory, then shook her head. ‘I don’t think we should come back.’ She glanced once towards the fissure, shuddered, and turned to go.

‘What’s that?’ Nona pointed to something gleaming among the rocks at Ara’s feet.

‘Oh.’ Ara didn’t look down. ‘It’s just a knife. Jula picked it up in the …’ She shrugged and turned to walk away.

‘Stay.’ Nona caught Ara’s hand in hers. ‘That thing in there … that monster. You remember it? Yes?’ Their fingers laced. Ara’s blue eyes met the darkness of Nona’s and for a moment there was a recognition of … something. Each took a step towards the other.

‘No.’ Ara shook her head. ‘I’m sorry.’ The fragile moment broke. She pulled free and hurried after the others. And Nona felt as if some chance that might never come again had escaped her.

Nona stood watching the five of them wind their way up the track zigzagging its way up towards the plateau.

What just happened?

You shouldn’t go back to the caves.

Don’t you try and pretend something didn’t just chase us out of there.

It did. A holothour. I told you.

So why are Ara and the others walking away?

They don’t want to die.

I mean why are they more concerned about having to wash their habits and stitch a few tears … There’s something more to this. Don’t lie to me, demon. I’ll force you into my fingers and hold them to the flame again.

I’ll chew your bones and make you spit blood!

But you know I’ll win. So tell me.

The fear tied them.

Untied?

The threads that bound them to that place, to these caves – the fear untied them. It set those memories loose. By the time they reach the top this will all have been a dream for them. The holothour made them forget.

And me? Why do I still care?

I protected you.

I don’t believe you. You’re made of lies.

Nona bent to pick up the knife. ‘I know this weapon.’ A straight blade, dark iron, just a faint tracery of rust, the pommel an iron ball, a narrow strip of leather wound around the hilt. A throwing knife. She had found one of the same design in her bed once, and seen another jutting from Sister Kettle’s side.

Keot reached above the collar of her habit, a hot flush rising. I know it too.

You liar. How would you?

The woman who held it came to see a dead man.

Why?

To understand the person who killed him, so that she might in turn kill them.

Nona asked the question though she knew the answer. Who did she come to see?

Raymel Tacis. He was dead but the mages wouldn’t let him die. And I was the first to find my way beneath his skin.

And the woman?

Was a Noi-Guin. Tasked to kill you.

8

In the week that followed Nona tried each day to broach the subject but none of her friends would do much more than admit, under pressure, that there might be caves beneath the Rock. It reached the point at which Nona saw Jula pretend not to notice her and turn a corner in order to avoid the chance of further questioning. She decided to drop the matter for a few days and see if the holothour’s mark would wear off and return her companions to her.

Mystic Class lessons continued to challenge. Nona improved with the sword, practising a handful of basic cut-and-thrust combinations until they started to feel natural. In Spirit Sister Wheel set them the task of writing an essay about a saint of their choice. Nona took herself to the convent library – the smaller one attached to the scriptorium rather than the larger store of holy texts held within the Dome of the Ancestor – to research. By the week’s end she had found three possible candidates from antiquity, all of whom had something in their story that would offend Mistress Spirit.

Sister Pan continued to immerse Nona, Zole, and Joeli in thread-work, showing them new tricks. Sometimes she would demonstrate thread effects most easily achieved whilst in the serenity trance, at other times fine-work requiring the clarity trance. Changing a person’s mood was something that might be achieved in a serenity trance, changing a particular decision required clarity. Neither were quick or easy to achieve, and Sister Pan warned that some people were much harder to manipulate than others.

Nona applied these lessons to the problem of the mark the holothour had set upon her friends. She could see the damage in the halo of threads around each girl but the solution lay beyond her skill. In the serenity trance she could see connections that must be undone or loosened. And in the clarity trance she could see entanglements on the smallest scale that would need to be unravelled. But working on either problem would make the other worse. They needed to be worked on together. Which required two people. And the only thread-worker she trusted to help, Ara, whose skills were pretty basic, was also one of those who needed fixing.

Sister Pan might be able to solve the problem but she clearly didn’t bother herself with thread-work on novices or she would have noticed Zole’s peculiar lack long ago. Nona could draw Sister Pan’s attention to the area of damage but the old woman would ask questions, and as she said: ‘everything’s connected’. Give Sister Pan one corner and she would soon pull out the whole story, and that would be the end of their adventuring.

Shade lessons focused on disguise. A whole week passed without mention of poisons, save to note some that were useful in small doses for altering the hue of a person’s skin or the colour of their eyes. Sister Apple likened the business of disguise to an extended lie told with the body, with the tone of one’s voice, and with the clothes that wrapped you. In Mystic Class every novice took the first of the Grey Trials, which involved crossing Thaybur Square undetected by other class members. Good disguise skills were a must!

In Academia Sister Rail made a spirited attempt to bore the class to death with mathematics. Nona felt she had achieved under Sister Rule, at great personal cost, a tenuous grip on arithmetic. A triumph, considering there were few people in her village who could count past twelve with confidence. Sister Rail introduced her to algebra, and not gently. The only moment of interest came when Darla, despairing of letters that were numbers but not any particular number, demanded to know what use such things were.

‘Our forebears used algebra to build the moon, novice!’ Sister Rail drew herself to her full height, which wasn’t much more than Darla’s when seated. ‘The curve of its mirror is governed by equations like these.’ A gesture to the chalk scrawls behind her. ‘It’s how they tightened the focus as the world grew colder. Other equations allow it to be steered as it was in the past, tilted to deal with the uneven advance of the ice.’

Nona frowned. Jula had mentioned something about changing the focus of the moon. Something she’d read about the Ark years ago: whoever owned the Ark could speak to the moon. ‘It could be a weapon.’

‘What’s that, Nona? Your expertise extends past assaulting classmates and reaches the moon now?’ Sister Rail tilted her head in inquiry.

Tittered laughter around Joeli.

‘It could be a weapon. If the focus was narrowed further it could burn cities.’

‘Nonsense. The moon is not a weapon of war. There’s no reason to believe the focus can be narrowed to that degree even if someone wanted to do it.’ Sister Rail waved the suggestion away with a bony hand.

‘If it can be tilted it could be steered from the Corridor entirely then returned,’ Nona said, staring at the glistening white of the globe on Rail’s desk. ‘Whole nations could be denied the focus and the ice would swallow them. It could melt vast lakes on the ice then connect them to the Corridor, washing away armies and cities …’

‘We were discussing the formula for a circle.’ Sister Rail banged a heel to the floorboards and the lesson sank back into a confusion of letters and symbols.

Nona had let the nun’s words slide past her and sat gazing at the distorted sky offered through puddle-glass windows. Memory filled her vision. Yisht stumbling away chased by shadow, the shipheart in her hand. Four shiphearts to open the Ark? One Ark to control the moon. One moon to own the world?

By the seven-day nothing had changed in the others’ reaction to talk of returning to the caves. Not ready to explore alone, Nona agreed to accompany Ara on a visit to Terra Mensis, a distant cousin of hers.

‘It’ll be great to get you off the Rock for once!’ Ara grinned, hugging her range-coat around her.

‘I don’t think the abbess plans to let me out on my own even when I’ve got the Red.’ Nona peered around the pillar, squinting against the ice-wind. The Mensis escort was late. They were sending a dozen of their house guard, enough to satisfy Abbess Glass that neither Ara nor Nona would be at risk from kidnap or assassination.

‘There is no point to strength if it is never tested.’ Zole stood in the open before the pillar forest, scowling at the world. Nona had been surprised when Ara extended the invitation to the ice-triber, more surprised when she accepted, and astounded when Abbess Glass permitted it. Nona supposed that Zole felt as trapped as she did on the Rock. Perhaps if the abbess worried that if Zole felt too trapped, she would simply run away.

Sister Kettle leaned against the pillar beside Nona and rolled her eyes, grinning. When Nona had heard the abbess was demanding an escort of her own in addition to the house troops she had worried they might get stuck with Sister Scar, Sister Rock or someone equally joyless. Perhaps even Sister Tallow. Nona respected Tallow but didn’t imagine she would be a particularly lenient chaperone in Verity. The arrival of Sister Kettle to watch over them had been a pleasant surprise. She still looked too young to be a nun. In the bathhouse with the black shock of her hair shaved to her scalp she could easily pass as a novice.

‘They’re coming.’ Kettle kept her back to the pillar.

Nona leaned out again. ‘Don’t see them.’ She spat an ice-flake. ‘Zole?’

Zole stood silent, leaning into the wind. Then, just as Nona was about to repeat herself, ‘I see something.’

A few minutes later the twelve guards swaddled in black furs that now hung with ice gathered around the nun and three novices. Sister Kettle cast an eye over each of them in turn then nodded and allowed them to lead the way, back towards the Vinery Stair.

‘Your cousin won’t be pleased to see me and Zole with you.’ Nona knew that any Sis would spot her peasant roots no matter how many years of convent education she might be carrying on top of them. ‘Well, she might be pleased to see Zole.’ The Argatha was a novelty. The rich could overlook low breeding in a novelty.