Полная версия

Flint and Silver

FINT

AND

SILVER

John Drake

For my beloved wife Most precious Most special Most dear

Contents

Cover

Title Page

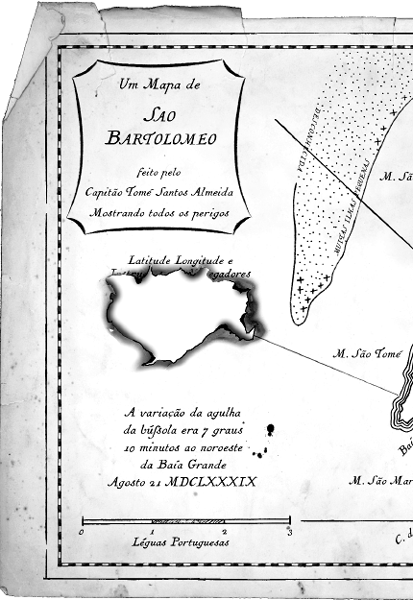

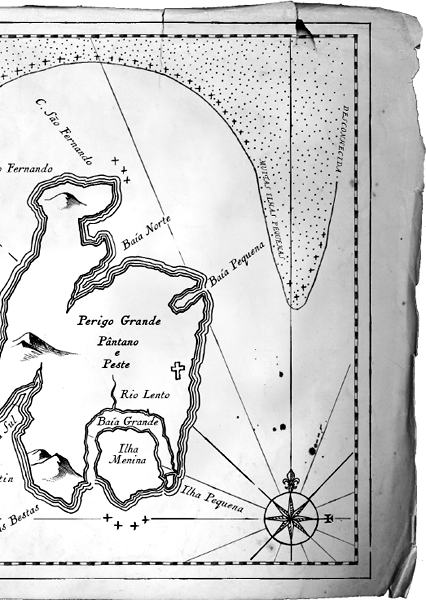

Map

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Afterword

Preview

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Chapter 1

15th March 1745 Off Madagascar

Ria de Ponteverde carried guns; most merchantmen did: carriage guns, with powder and shot, rammers and sponges, trucks and tackles. They differed from ships of the various royal navies only in the relatively small degree of their armament, as compared with the exclusive concentration upon artillery that marked out the man-o’-war.

And it wasn’t just a broadside battery on the main deck. It was swivels on the gunwale, and small arms in the lockers down below: muskets and pistols, pikes and cutlasses, and all the gear that went with them – cartridges, flints, powder horns and small-grained pistol powder. All this was a fearful expense and a burden upon trade, for there was not one farthing’s profit to be made by honest seamen in hauling defensive arms and ammunition across the seven seas.

Unfortunately there were others on the seas who were not honest seamen, and whose business it was to become very rich, very quickly by selling cargoes without the bother of paying for them. Hence the need for guns, because sometimes –indeed often – these gentlemen could be seen off by force. Sometimes, but not always. And now, six miles off the Bahia de Bombetoka, a general slaughter was about to begin.

The Portuguese brig Ria de Ponteverde and the buccaneer Victory were locked yardarm to yardarm in a stinking cloud of powder smoke that barely shifted in the hot, tropical air. The brig was beaten. She was broken, bloodied, smashed and splintered; her helm was shot away, her sails in shreds and Victory’s boarders were pouring over her sides.

A tall yellow-haired Englishman stood with his Portuguese mates by Ria de Ponteverde’s mainmast among the shattered spars and dismounted guns, the silent dead and the howling wounded, as the boarders came through the smoke cheering and hacking and killing. Firearms boomed and jumped on either side. Right next to the Englishman, his captain, José Carmo Costa, took the flash and thunder of a blunderbuss at close range, blowing large parts of his heart, lungs and breastbone clear out through the back of his shirt.

Then it was cold steel, hand to hand, and no quarter asked or given.

The Englishman swung a cutlass with all his might. He was a big man: muscular, quick and agile with long limbs and not a scrap of fat on his body. The blow came down like the wrath of God and caught his first man – fair, square and smack – on top of the head.

The heavy blade clove to the teeth, slicing bone, brains, meat and gristle. Number one dropped twitching and shivering, and the blade jerked free with a disgusting schlik. Then a dozen men, jammed in ferocious fight, rolled into the Englishman and a bedlam of noise beat at his ears. Arms, blades and bludgeons worked busily all around and instinctively he kicked and elbowed with enormous strength, clearing a fighting space around him, and – seizing the instant chance – ran the point of his weapon into the middle of his second man, who yelped and twisted and tried to pull free. But the pirate stumbled and went over face down, and the Englishman stamped a heel snapping and crunching into the base of his victim’s spine while he leaned mightily on his sword arm, driving the blade through the wriggling body and into the planks of the deck, even as the dense press of combat knocked him clear, still gripping the slimy hilt.

He cut down number three with two strokes: the first shearing fingers, the second splitting a face. Four and five took just a single cut each, one to left and one to right; a tall black with rings in his ears, and a squint-eyed barrel-chested fellow armed with a boarding pike.

Six was the hardest. He was a small man with a straw hat, striped breeches, quick feet and a straight-bladed sword honed to a wicked point, which he used to the exclusion of the edge. This man was a swordsman, which the Englishman was not – he had now to learn or to die.

Sweat flew as he wrenched his cutlass to and fro, trying with sheer speed and force to overcome skill. Ssssk! The cutlass blade sliced a larynx without killing. Jab! Jab! Jab! The rapier missed twice then sank an inch into the Englishman’s side, before he beat it clear with a clash and a scrape of steel. Jab! Into his hip. Chunk! And the tip of the swordsman’s elbow was off like the top of a breakfast egg. Jab! Into the Englishman’s cheek. Swish! Through the straw hat, slicing away hair and a patch of scalp. Then a blur of light and the Englishman cut hard into the right side of the other’s neck, sinking the blade through flesh, fat and marrow to within an inch of the left-hand side, almost but not quite taking the head clean off.

He gasped and shuddered as his man went down. He’d fought before, but only with his fists. It’d been just fights over girls or drink, or because a man had given offence. For that he’d drawn blood and cracked heads. He’d grown up in a hard school. But he’d never before fought with weapons and the serious intent to kill. In fact he’d never killed a man … except that now he had. He’d just killed six of them.

Now he looked around and saw that he was the last man standing of Ria de Ponteverde’s crew. The others were either dead or dying, or having their throats cut before his eyes by the buccaneers. The fight was over and the enemy ringed him, raising their weapons warily. There were no guns left loaded or they’d have shot him for sure. They’d won the fight, but they’d taken the measure of this fair-haired killer who stood head and shoulders taller than any of them, and they were being careful.

He spun on his heel, chest heaving and breath coming in deep gasps that left the taste of blood at the back of his throat. He screwed the sweat out of his eyes with his left hand, and took a firmer grasp of the cutlass hilt. The edge was nicked like a saw, but it would still cut. They edged in closer all around him: angry faces, pike heads, swords, dirks and hatchets.

“Bastard!” said a voice. “You done for my mate.”

“Skin him!” said another.

“Boil him!”

“Woodle him!”

“Burn him!”

“Come on then!” he roared. “Come one, come all!” His voice was high and cracked. It was near a shriek. He was in an uncanny state of mind: wound up tight with the blood of battle, heart thundering, nerves at hair-trigger. He was outnumbered beyond hope, but still highly dangerous, and none of those around him sought the honour of being next to fight him.

“Aaah!” he cried, and stamped forward a pace.

“ ‘Ware the bugger!” they shouted, and “Cuidado!” and “En garde!” They fell back, only to close in behind him. He slashed at a pikestaff thrust by a big-nosed fellow with lank black hair. He clashed blades with a hanger wielded by a bare-chested mulatto with a face scarred in a dozen fights. He spun round to catch a red-haired Irishman trying to spit him on the sly. Red-hair darted back, howling from a shoulder slashed to the bone, and lucky it wasn’t his skull.

“Henri!” cried a man in the front rank, yelling back over his shoulder and holding up an empty musket, “Apporte moi de la poudre et balle!” There was a swirl in the crowd and a cartridge was thrust into the Frenchman’s hand.

“Aye!” they roared. “Drop the sod, Jean-Paul!”

“Je déchargerai la tête du con!” he muttered, and bit his cartridge, priming the pan and snapping down the steel. He grounded the butt, stuffed the rest of the cartridge into the muzzle and drew out the ramrod to firm home the charge down the long barrel. The Englishman leapt forward, trying to cut down the musketeer before he could reload. But they’d thought of that. They were already clustered protectively around Jean-Paul, with pikes presented to keep him safe.

There was a rattling clatter of steel against ash, and the Englishman was driven back bleeding from a stab to his shin, and another to his arm. Frustrated, hopeless and fearful, he watched Jean-Paul finish his loading, cock the musket and slowly take aim.

He saw the round, black muzzle come up and fix on him. He saw Jean-Paul’s eye glinting over the breech, alongside of the lock. He leapt to the right. The musket followed. He leapt to the left. It followed again. And behind Jean-Paul, others were busy loading. It was no good. Muskets were not renowned for accuracy, but Jean-Paul’s was no more than ten feet from the Englishman’s chest.

“Fuck you, you bastard!” he spat. Jean-Paul bowed extravagantly.

“Merci, monsieur,” he said. “Et va te faire foutre!”

“Go to it, then!” said the Englishman. “And a curse on the pack of you!” He threw down his cutlass, spread out his arms and closed his eyes. At least it would be quick. Not like what they’d threatened.

Jean-Paul took up the slack on the trigger. He squeezed harder. The lock snapped. It sparked brightly. The gun roared. Three drachms of King George’s best powder exploded, driving the heavy musket ball violently out of the barrel … to soar in a majestic parabola, higher than a cathedral steeple, and then to curve down into the sea, where it fizzed viciously for a few feet until its power was spent, and then proceeded gently on its way down to the sea bed, where the fishes nosed it for a while and then ignored it.

“Belay there!” cried a loud voice, with all the confidence of command. Nathan England, duly elected captain of the buccaneers, had just knocked the barrel of Jean-Paul’s musket skyward.

“I say we keep him!” he said, pointing his sword at Jean-Paul’s target. “You there!” he said. “You can open your eyes … Ouvrez les yeux! … Entiendez? … Capisce?” England’s crew were the dregs of half a dozen seafaring nations and he was used to making himself understood in whatever tongue suited.

The Englishman blinked. He stupidly ran his hands over his body to feel for a wound.

“Portugês?” said England. “Français? Español?”

“English, damn you!”

“Huh!” said England. “Rather bless me, you ungrateful bugger, for I’ve a mind to let you live. I’m several men adrift, courtesy of yourself, and I don’t see why you shouldn’t make up some of the loss.”

“I’m no bloody pirate!” said the Englishman.

“Neither am I,” said England. “Nor my men, neither. We’re gentlemen of fortune! Brethren of the coast!”

“Horseshit!” the Englishman sneered. “Same bird, different name.”

Hmm, thought England, taking the measure of the big man with his broad, square face – pale for a seaman – and his stubborn jaw and angry eyes. “Now see here, my bucko,” said England, “I’ve neither time nor inclination to educate you. The fact is, I saw you fight Little Sam, who was the best among us. And you killed him.”

“And why not?” said the Englishman, not realising he was being praised. “Didn’t you take our bloody ship and kill my mates?” He pointed at the body of Captain Carmo Costa, still smouldering from the charge that had killed him. “That’s my captain there, and him not a bad bastard neither.”

England frowned. He was not a patient man. He stuck his thumbs in his belt and drummed his fingers on the tight leather. “Now, here’s the long and short of it,” said he. “We must come to a swift agreement, you and I, my lad. I like the way you fight, and I have the fancy to admit you into our company. So you can either sign articles and join us …” Glancing over his shoulder at Jean-Paul with his smoking musket, England commanded, “Recharges, enfant!” Then he nodded at the Englishman and concluded with a smile: “… Or you’ll be shot where you stand.” As far as England was concerned, the matter was resolved.

Quickly, another cartridge was found for Jean-Paul, and he grinned merrily as he plied his ramrod. Meanwhile Captain England drummed his fingers on his belt.

“So, what’s it to be?” he said. “For as soon as mon ami has loaded, he may open fire, and that’s the truth.”

“Damn you all!” said the Englishman, and Jean-Paul cocked and aimed.

“Je tire, mon capitaine?”

“Last chance, my cocker,” said England, as Jean-Paul began to squeeze the trigger.

“Avast!” said the Englishman, and made the only choice that any decent man could make in the circumstances. A precious saint might have said no, and the Lord Jesus Christ certainly would have, but who wants one of them for a shipmate, anyway?

With all matters of recruitment concluded, England’s men set briskly to work aboard the two ships, mending and splicing above, plugging and hammering below. These things they did with practised skill, and did them well, since the lives of all aboard might depend on the work. They also buried the dead with due respect, and they cleaned and scoured the decks after their fashion. As for the wounded, they were attended by the drunken butcher that served England for a surgeon. He was of the “boiling pitch” school when it came to staunching bleeding, and the crew were more afraid of him than of the hangman. But he was what they’d got.

Victory and Ria de Ponteverde sailed in company within hours of the battle, and that evening the yellow-haired Englishman was welcomed into England’s crew as a fellow gentleman of fortune. The ceremony was half farce and half deadly earnest, with all hands mustered round the mainmast and the rum flowing freely. England presided in his best clothes, a plumed hat, and seated on a massive carved armchair brought up from his cabin.

The proceedings owed much to the horse-play of crossing the equator, with a ludicrous bathing and soaping, and the postulant stripped naked and blindfolded. Finally, England hammered on the deck with the narwhal tusk he carried as a staff of office.

“Now, brothers,” he cried, “we stand ready to admit this child as a free companion. So pull the blindfold off him, Mr Mate, and put a sharpened sword into his hand.” This was done and the Englishman stood blinking and puzzled and looking about him. The mob of armed men were swaying in silence on the heaving decks, bracing themselves with such ease that they weren’t even aware of doing it.

“So,” said England, “if any brother knows of any just impediment why this child should not be admitted, then let him speak now or for ever hold his peace!”

This parody of the wedding ceremony served the entirely practical purpose of ensuring that any man who’d lost a friend to the child must challenge him at once or accept him as a shipmate in good faith. With six dead to his credit, this was an interesting moment for the crew, and there was much hopeful shuffling and muttering and looking to those who had lost their messmates. One or two of the bereaved found it expedient to consider their boots at this moment, while others brazened it out with fixed smiles and knowing winks. But much to the disappointment of those free of obligations, nobody wanted to fight.

“So be it!” cried England when he thought sufficient time had passed. “And now, brother-that-you-have-become, I asks you to sign articles as all others have done before you.”

At this, England’s first mate stepped forward and laid down a big book upon a barrel that was set before England as a table. Pen and ink and a sand-caster were ready to hand. The book was black-bound in leather and had once been the master’s journal aboard an honest merchantman. But the long-dead navigator’s written pages had been cut out and a series of numbered items entered in a large, bold hand on the first remaining page.

“Are you a scholar, brother?” said England. “Or will you have me read these articles to you, before you make your mark?”

“I know my letters,” said the Englishman.

“Well enough to read?”

“Aye!”

“Oh?” said England, for, saving the mates and the gunner, not one other man in his crew could do the like. “Then read, brother, and read boldly for all to hear!” The Englishman picked up the book and held it close to a lantern to catch the light.

“These articles …”

“Louder!” cried England. “So those aloft can hear.” He pointed to the tops where the lookouts were stationed.

“These articles,” roared the new brother, “I do enter into freely and volunteerly and thus do I solemnly swear. Article one: that I shall obey the commands of my captain in all matters of seafaring and warfare, upon pain of the law of Moses, viz: forty lashes – barring one – upon the bare back …”

And so it went on. There were twenty-three articles in England’s book, mainly self-evident statements of the need for discipline on board any ship that ever went to sea in all of mankind’s history. There was much other good sense too, on such matters as forbidding the dangerous business of smoking below decks, and the filthy business of pissing in the ballast, which lazy sailormen will do who can’t be bothered to go to the heads on a dark night. Anyone caught doing that was obliged to drink a pint of the same liquid, piping hot, donated by his messmates. Also, there were ferocious punishments for taking private shares of the loot before its formal division. In all these matters, the articles were similar to those in use by numerous other freebooters and buccaneers currently doing business in the Indian Ocean and Caribbean.

But England’s articles had some extras. He punished rape by castration, torture by hanging, and sodomy by dropping the offenders over the side, bound together, with roundshot tied to their feet. These eccentricities the crew took in good part (even the astounding prohibition of rape) because England was a fine and lucky seaman with a nose for smelling out gold.

So the new brother worked his way through the list till he came to the end, where followed four clear signatures, one obviously that of the draughtsman of the articles, plus a few painfully worked names such as children might attempt, then several hundred crosses, marks and scrawled drawings: some of fish, or birds, or animals, some of hanged men, some skulls-and-crossbones, and one splendid likeness of a face, the size of a penny piece, as finely drawn as the work of any London caricaturist, which was the mark of an illiterate man who nonetheless had this remarkable gift. Each mark had a name beside it in the draughtsman’s hand. Many (including the likeness) were neatly ruled out in red ink, with a date beneath it. These were the dead.

The Englishman sighed. He took up the pen, dipped it into the ink, and paused. In fact he was only half an Englishman, for his seafaring Portuguese father had married an English girl and settled in Bristol. The son had taken his father’s size and strength, his mother’s yellow hair, and at thirteen had run away to sea to escape his father’s belt. His name, as given to him by his father, had been João De Silva: a foreign-sounding name to some and therefore tainted, but not to him. Unlike the vast body of land-rooted, home-fast Englishmen, he had no disdain of things foreign, because seafaring men are an international breed taught by hard reality to know that all races have their strengths and weaknesses, and the only thing that matters is how your shipmate behaves when the sea turns nasty – and certainly not the land of his birth. But for all that he was still an Englishman in his loyalties, and so he signed with a flourish as …

Chapter 2

4th January 1749 Aboard HMS Elizabeth The Caribbean

Captain Springer controlled his anger with effort.

“Lieutenant Flint,” he said, “I swear that if I hear that tale once more, I shall put you in irons.”

“Will you, though?” said Flint. “Then I pray that you may be cursed as I was. Four years under Anson, suffering scurvy, shipwreck and sores, only to see thirty-two wagons full of gold unloaded at London, and not a penny piece was my share!”

Springer glanced around the quarterdeck. The mids and the seamen were muttering and looking sly. Mr Bones, the master’s mate, was staring attentively at Flint as if waiting for some word of command. Springer ground his teeth, Bones was Flint’s man through and through, while next to him, Dawson, the sergeant of marines – who was loyal to Springer – was glaring his contempt at this public squabbling.

“Mr Flint,” said Springer, “a word.”

Springer walked up the sloping deck to the weather side and waited for Flint to join him while the crew looked on in wary fascination. Springer was pure tarpaulin: lumpish, heavy and elderly with a fat lower lip, watery eyes and a bristling white stubble that no razor ever conquered, while Flint was smooth as a cat, with an olive, Mediterranean skin. He moved like an athlete and had a beautiful, brilliant smile. He was slim-built and only of average height, but men always thought of him as tall.

Together, these two opposites stood locked in argument in their long blue coats with the brass buttons.

These uniform coats were badges of rank which few officers were wearing as yet, for they were an innovation introduced only the previous year. But Elizabeth’s officers all had them, thanks to Lieutenant Flint, who, wanting a smart ship, had spent his own money to get them – including one for Springer, who’d never have bothered if left to himself.